Hempstead (village), New York

The Incorporated Village of Hempstead is located in the Town of Hempstead, Nassau County, New York, United States. The population was 53,891 at the 2010 census,[6] but by 2019 had reached 55,113 according to the U.S. Census Bureau estimate.[7] It is the most densely populated village in New York. Hempstead Village is the site of the seventeenth-century "town spot" from which English and Dutch settlers developed the Town of Hempstead, the Town of North Hempstead, and ultimately Nassau County.

Hempstead, New York | |

|---|---|

Village and town seat | |

| Incorporated Village of Hempstead[1][2] | |

Seal | |

_highlighted.svg.png.webp) Location in Nassau County and the state of New York. | |

Hempstead Location within the state of New York  Hempstead Hempstead (New York)  Hempstead Hempstead (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 40°42′17″N 73°37′2″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Region | Long Island |

| County | |

| Town | Town of Hempstead |

| Settled | 1643 |

| Incorporated | 1853 |

| Named for | Heemstede, Netherlands |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Don Ryan (R) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.69 sq mi (9.56 km2) |

| • Land | 3.68 sq mi (9.54 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 53,891 |

| • Estimate (2019)[5] | 55,113 |

| • Density | 14,960.10/sq mi (5,775.42/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| FIPS code | 36-33139 |

| Website | villageofhempstead |

| New Netherland series |

|---|

| Exploration |

| Fortifications: |

| Settlements: |

| The Patroon System |

|

| People of New Netherland |

| Flushing Remonstrance |

|

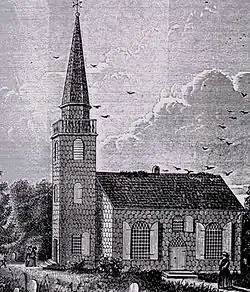

Several of Nassau County's most historically valuable buildings are in the Village of Hempstead, including Town of Hempstead Town Hall (built in 1918), Carman-Irish Hall at 160 Marvin Avenue (built about 1700), St. George's Episcopal Church (319 Front Street, erected 1822), St. George's Rectory (217 Peninsula Boulevard, built 1793), and the United Methodist Church at 40 Washington Street (erected 1855).[8] The Carman-Irish Hall is occupied by American Legion Post 390. The church structures have been in continuous use by their congregations since they were built.

Christ's First Presbyterian Church at 353 Fulton Avenue is Nassau County's oldest Presbyterian congregation, and one of the earliest in the United States, having been founded in 1644 by Richard Denton.

Jackson Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church, housed at 60 Peninsula Boulevard since the mid-1950s, was established between 1825 and 1840.[8] It is one of the county's oldest African American congregations.

Diversity has long been a characteristic of Hempstead. While it was majority white until the mid-twentieth century, Hempstead had a significant black population from about 1651 onward, in addition to the native peoples still living on Long Island. Starting in the nineteenth century, Hempstead's diversity increased. Irish, Polish, and German immigrants arrived during the second half of the nineteenth century to join the descendants of the original English and Dutch settlers. Military personnel were trained at Camp Mills during 1918 and at Mitchel Field during World War II, and some stayed to raise families, adding other European-descent groups and African Americans. During the first half of the twentieth century, African Americans from the South who sought opportunities in the North established homes and businesses in Hempstead. Nassau County's first chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was established in Hempstead in 1932. A major case against de facto segregation in Hempstead was taken to the New York State Supreme Court in 1949 by Thurgood Marshall. From the 1950s forward, the village's African American population has increased, and so have Mexican, Central American, and South American groups, as well as Caribbean immigrants, Middle Easterners, and Asians, especially Indians and South Asians. [9]

Hofstra University (founded 1934) is located in Hempstead.[10]

History

Foundation

The land on which the Village of Hempstead stands was under Dutch control from the early 1620s. The Dutch West India Company established, first a trading post in 1613, and then the community of New Amsterdam at the southern tip of Manhattan. Dutch colonies were founded in what is now New Jersey as well as the western half of Long Island. Attracting a sufficient quantity of Dutch settlers to colonize the land, however, proved difficult.[12]

Meanwhile, European traders from France, Spain, Holland, and England set up trading posts along the Atlantic Coast; Native Americans had been encountering Europeans since Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed into New York Harbor on April 17, 1524. Starting with the Pilgrims in 1620, English citizens founded the colonies of Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut. A Presbyterian minister named Richard Denton came from Yorkshire, England, to join the Massachusetts Bay colony. He then went to Connecticut and helped establish both Wethersfield and Stamford.

These colonies were threatened by wars among the Pequots, Narragansetts, and Mohegans. The Pequots had for decades forcibly exerted control over much of the area that became New England, subjugating the Mohegans and many other Algonquian-speaking groups, such as the Narragansett. The Pequots controlled the wampum and fur trades with the Europeans. Initially the Pequots lived peacefully with the Puritans and other English colonists of New England, but as English communities grew, the Pequots felt pressured by loss of territory. They began to trade exclusively with the Dutch, who were centered in New Amsterdam. Native groups resentful of Pequot control (mainly Mohegan and Narragansett) allied with the English. War broke out, culminating in the ugly Pequot War of 1636-1637, which broke the dominance of the Pequots.[13]

Relations between Dutch and Indians in western Long Island, and between English and Indians on eastern Long Island, while never truly equal, were more peaceful than in New England. Incidents of violence and misunderstanding did occur during European encounters with the Native Americans along the Hudson River after Henry Hudson reached Manhattan in 1609. However, the native groups had something that the Europeans badly wanted (furs) and the native groups willingly traded furs for the brightly colored European coats and other clothing, as well as for European-style beads, firearms, metal tools, and at times alcohol. The relations between the foreigners and the natives therefore continued to develop.[14] The Pequot defeat in 1636-1637 meant Long Island Native Americans were no longer subject to Pequot dominance, and were free to establish their own complex dealings with the Europeans.[15]

The Dutch needed to populate Long Island or lose control of the territory. They invited New England colonists to found new settlements on Long Island, as long as the English settlers agreed to Dutch sovereignty.[16] Possibly the English had visited Long Island during the late 1630s and early 1640s.[13] A dreadful series of raids on Native American groups mainly in Staten Island and Manhattan, provoked and sustained by then-Dutch Governor Willem Kieft during 1640-1645, evoked retaliatory action from the Native groups, and led ultimately to the deaths of 1,000+ Native Americans and a few dozen white settlers (mostly Dutch). This unfortunate series of battles was known as Kieft's War, and was finally ended with a treaty signed in Manhattan in 1645.[17] These perturbances could have deterred further European settlements in western Long Island. However, at a lull in Kieft's War, a Long Island Native leader known as Sachem Pennawitz represented Long Island's Native groups in a peace agreement with the Dutch on March 4, 1643.[18] This peace agreement was the precursor to the 1643 journey of colonists from Stamford to mid-Long Island.

In the fall of 1643, two of Rev. Denton's followers, Robert Fordham and John Carman, crossed Long Island Sound by rowboat to negotiate with the local inhabitants (Indians) for a tract of land upon which to establish a new community or "town spot". Representatives of the Marsapeague (Massapequa), Mericock (Merrick), Matinecock and Rekowake (Rockaway) tribes met with the two men at a site slightly west of the current Denton Green in Hempstead Village. Tackapousha, who was the sachem (chief spokesman) of the Marsapeague, was the acknowledged spokesman for conducting the transaction.[19] The Indians sold approximately 64,000 acres (260 km2), the present day towns of Hempstead and North Hempstead, for an unknown quantity of items; a 1657 revisit of this agreement names large and small cattle, stockings, wampum, hatchets, knives, trading cloth, powder, and lead given as payment by the English.[20] Some items may have been valuable to the Native Americans in terms of the contemporary markets for European "trinkets," which may have held symbolic and spiritual importance to Native America peoples in the Northeast.[21]

The 1643 transaction is depicted in a mural in Hempstead Village Hall, reproduced from a poster commemorating the 300th anniversary of Hempstead.

In the spring of 1644, thirty to forty families left Stamford, Connecticut, crossed Long Island Sound, landed in Hempstead Harbor and eventually made their way to the present site of the village of Hempstead where they began their English settlement within Dutch-controlled New Netherland. The settling of Hempstead marked the beginnings of the oldest English settlement in what is now Nassau County. Subsequent trips across the Sound brought more settlers who prepared a fort here for their mutual protection. These original Hempstead settlers were Puritans in search of a place where they could more freely express their particular brand of Protestantism. They established a Presbyterian church that is the oldest continually active Presbyterian congregation in the nation.[19] In 1843, Benjamin F. Thompson wrote and published a history of the village, and an account of contemporary Hempstead Village. Thompson reported that there were 200 dwellings, and 1,400 residents; that the village was connected to New York City by a Turnpike and a railroad; that it had dry soil, excellent water, and pure air; and that it was the principal place of mercantile, and mechanical business, in the county. The village of Hempstead was incorporated on May 6, 1853, becoming the first community in Queens County (Nassau County did not exist as a separate county until 1899) to do so.[2]

Regarding the origin of the name "Hempstead", Hempstead founder John Carman was born in 1606 in Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, England, on ancestral land recorded in the 2nd historic census of England (under Edward the First), the Rotuli Hundredorum (Hundred Rolls) AD 1273 as being owned by his direct ancestor Henry Carman. These same properties were on record continuously as being owned by Henry's descendants, through John Carman of 1606. John's wife Florence and her father, Rev. Robert Fordham, were from the county of Surrey, England.[19] Another theory regarding the origin of the name 'Hempstead' is that it is derived from the Dutch town of 'Heemstede' in the Netherlands, as this was an area from which many Dutch settlers of New Netherland originated. Several of Hempstead's original fifty patentees had Dutch surnames. In 1664, the new settlement adopted the Duke's Laws, an austere set of laws that became the basis upon which the laws of many colonies were to be founded. For a time, Hempstead became known as "Old Blue," as a result of the "Blue Laws".[2]

Rise

As the years passed, the population of Hempstead increased, as did its importance and prestige. Between 1703 and 1705, the newly formed St. George's Church, which would not have been called "Episcopal" then, but was under the established Church of England, received a silver communion service from England's Queen Anne.[2] Right after he became President, George Washington made a tour of Long Island, stopping overnight at Sammis Tavern here (Nehemiah Sammis's Inn established between 1660 and 1680[22]). Hempstead can boast of its share of celebrities. Peter Cooper, inventor and politician, lived with his brother in Hempstead until he married Sarah Bedell of Hempstead on Dec. 18, 1813, and settled there 1814-1818.[23] During this time, he invented the self-rocking cradle, which he patented on March 27, 1815.[24] His house was moved from Hempstead to Old Bethpage Restoration Village in about 1965, and still contains the cradle. During the 1820s on, he and his family lived in the city of New York, where he patented many inventions and in 1859 established The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a major experiment in adult education which operates still in lower Manhattan.[25][26] Cooper ran for President on the "Greenback" ticket. Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, spent her summers here between ages 4 and 8, when her father Elliott Roosevelt owned a summer home on Richardson place (now the site of the manse for St. Laudislaus RC Church). Lionel Barrymore reputedly lived at 75 Marvin Avenue.

During the American Revolution, Hempstead was a center of British sympathizers or Tories, as they were known.[27] The British attempted to occupy Hempstead after the Battle of Long Island,[27] and used St. George's as a headquarters as well as a place to worship. Judge Thomas Jones faulted a lax peace treaty for forcing the evacuation of the loyalists.

In 1845, future Major League Baseball catcher Nat Hicks was born in Hempstead. Before Nat Hicks, baseball catchers would stand approximately 25 feet behind the batter, catching the pitched baseball on a bounce, since there were no gloves or protective gear. Pitchers would not throw curveballs because they would likely be wild pitches. In 1872 while playing for a Brooklyn team, Hicks stood directly behind the batter, catching the pitched baseball in flight instead of on a bounce. This allowed his teammate, pitcher Cummings, to throw curveballs. Hicks was badly injured often but he changed baseball fundamentally. This repositing of catcher by Hicks facilitated pictures throwing breaking balls, throwing over-hand instead of underhand, made the game faster paced, and necessitated the need for new inventions such as baseball gloves, catchers protective gear, and the facemask.[28][29]

In the 19th century, Hempstead became increasingly important as a trading center for Long Island. In 1853 it became the first self-governing incorporated village. Many prominent families such as the Vanderbilts and the Belmonts built homes here, making Hempstead a center of Long Island society. Hempstead merchants established routes out to outlying farms and served as a distribution point for many firms. Wagons would leave Hempstead loaded with tobacco, candy, and cigarettes and return in a week to restock. Bakeries covered routes from Baldwin to Far Rockaway daily. Butchers ran routes to Seaford, Elmont, Valley Stream, Wantagh, East Meadow, Creedmoor, East Rockaway and Christian Hook. Drugs, medicines, perfumes, extracts, aprons, children's coats and dresses and men's clothes were peddled about the country by Hempstead merchants. People came from all sections of Queens to purchase stoves, and there were few places outside Hempstead where stoves could be purchased. Hempstead was the shopping center for Nassau County and the eastern portion of Queens, those settlements east of Jamaica before 1900 when Nassau County was established, following the creation of the City of Greater New York in 1898. Hempstead has historically been the center of commercial activity for the eastern counties of Long Island. In Nassau County, all major county roads emanate from this village. It is indeed the "Hub" of Nassau County. During the 18th and 19th centuries, all stage coaches en route to eastern Long Island from Brooklyn passed through Hempstead. Today, seventeen bus routes and three interstate buses leave from the village every day. In addition, the Hempstead Branch of the Long Island Rail Road has its terminal here. At one time, there were three railroad companies with terminals within the village.[30]

In March 1898, Camp Black was formed on the Hempstead Plains (roughly the shared location of Hempstead and Garden City), in support of the impending Spanish–American War. Camp Black was bounded on the north by Old Country Road, on the west by Clinton Road, and on the south by the Central Line rail. Camp Black was opened on April 29, 1898 as a training facility and a point of embarkation for troops.[31]

Charles A. Lindbergh, arguably the world's most famous aviator, spent quite a bit of time in Hempstead both before and after his epic solo flight from nearby Roosevelt Field to Le Bourget Field in Paris, France on May 20, 1927.[19] While living here, Christopher Morley was so enamored with the place that on the three hundredth anniversary of its founding he wrote a beautiful essay in tribute. His first novel, Parnassus on Wheels, was written on a kitchen table at his Oak Street, Hempstead home in 1917.[32] In 1704 the first stage coach on Long Island stopped to water its horses here.[33]

Early Long Islanders made their living in agriculture or from the sea. Hempstead, with its central location, became the marketplace for the outlying rural farming communities. It was a natural progression, as the surrounding areas developed from small farms into today's suburbia, that Hempstead Village would remain as the marketplace. Chain department stores such as Arnold Constable and Abraham & Straus called Hempstead home for many years. Hempstead's Abraham & Straus was the largest grossing suburban department store in the country during the late 1960s. Hempstead was Nassau's retail center during the 1940s through the 1960s. The advent of regional shopping malls such as the one at nearby Roosevelt Field, the demise of nearby Mitchel Air Force Base in 1961 as well as the changing demographics put the retail trade in the village into a downward spiral that it was unable to recover from during the recessions of the 1970s and 1980s. A plethora of businesses left the village in the 1980s and early 1990s, notably retail giant, Abraham & Straus.[34]

Recent years

In the course of the 1990s the village saw redevelopment as a government center as well as business center.[35][36] There are more government employees from all levels of government in the village than there are in the county seat in Mineola. According to James York, the municipal historian, writing in 1998, the population during the day might rise to nearly 200,000, from a normal census of 50,000.[19] Retailers' interest in the village was rekindled, due to the aggressive revitalization efforts of former Mayor James Garner, who served from 1989 to 2005, and former Community Development Agency Commissioner, Glen Spiritis, who served under Garner's administration.[35][36] Specifically, two large tracts of retail property have recently undergone redevelopment. The former 8.8-acre (36,000 m2) Times Squares Stores (or TSS) property on Peninsula Boulevard and Franklin Street has been redeveloped as Hempstead Village Commons, a 100,000-square-foot (9,300 m2) retail center including Pep Boys and Staples. The former Abraham & Straus department store on 17 acres (69,000 m2) has recently undergone demolition and been replaced by a large retail development consisting of Home Depot, Old Navy, Stop & Shop and many other smaller establishments. A considerable infusion of state and federal funding as well as private investment have enabled the replacement of blighted storefronts, complete commercial building rehabilitations and the development of affordable housing for the local population. The replacement of the 1913 Long Island Rail Road Hempstead Terminal with a modern facility was completed in 2002,[37] and a four-story, 112-unit building for senior housing, with retail on the ground level was completed at Main and West Columbia Streets in January 1998. Thirty two units of affordable townhouses known as Patterson Mews at Henry Street and Baldwin Road was completed and fully occupied in 1997.

In 1989, Hempstead residents elected James A. Garner (R) as their mayor.[36] He was the first Black or African-American mayor ever elected to office on Long Island, and he served for four consecutive terms.[36] Subsequently, Wayne Hall, a former Village of Hempstead trustee who is also African American, served as mayor for three terms, from 2005 to 2017.[38][39]

The first African-American male judge, Lance Clarke, was elected in 2001. Cynthia Diaz-Wilson was the first female justice in the Village of Hempstead and first African American village justice in the state of New York.

In recent years, there has been concern regarding ongoing gang activity in certain neighborhoods, notably the "Heights", in addition to the issue of illegal rentals (homes/apartments that are illegally-subdivided by slumlords) and racial steering.[40] Hempstead was also one of the first Long Island communities that had to deal with the Salvadoran gang, MS-13 or "La Mara Salvatrucha".[41] The continual intra-violence this gang has exhibited has led to the formation of their arch-rivals, "SWP" or "Salvadorans with Pride". These issues have contributed to Hempstead's high crime rate as compared to other communities in the area.[41]

This issue is worsened by racial steering - especially by charities that are paid by the US Government for each immigrant that they relocate.[42][43][44] Many times, they are steered into/away from certain communities, despite the Fair Housing Act.[45][46][47]

Today

Hempstead has developed into the most populous village in the state of New York, with a population in excess of 50,000 people. It is also the seat of government for the town of Hempstead, the largest minor civil division in the nation with over seven hundred thousand people. Hempstead is just as urban (at least with regard to population density and activity) as any major city. In stark contrast to the surrounding villages in the town and county, it is more densely populated than many American cities with exception to New York City, Long Beach, New York; Mount Vernon, New York; Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts; San Francisco, California; Santa Ana, California; and Jersey City and Paterson, New Jersey.

Hempstead consists of several areas or neighborhoods that are distinct in character. Some enclaves have a reputation of being the source of crime, some are known to be populated by indigent residents, others consist of middle income residents and homeowners, while others boast stately homes with relatively little incidence of criminal activity. The area has a mixture of homes and apartment complexes throughout the area. Originally, there were two known sides of town, "The Heights" (Hempstead Heights) and "The Hills" (Hempstead Hills). Hempstead Heights is the area east of Clinton St and west of Westbury Blvd. Over the years, several new regions, or "turfs" have informally been established, including "Terrace" (also known as "TA" or Terrace Ave.), "Parkside", "Trackside" and "Midway","D-Block".

There are over fifty religious institutions located in the village of Hempstead. They include a vast range of denominations, including, Roman Catholic, (Eastern Catholic) Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Orthodox, Methodist, Seventh-day Adventists, Baptist, Lutheran and other Christian churches, a Hindu temple, a Sikh Gurudwara, a Korean temple, a Hebrew Congregation and a host of smaller congregations.[33]

Government

The Hempstead Village government is currently headed by mayor Don Ryan, who defeated three-term mayor Wayne Hall in the March 2017 election.[39] Ryan ran under the "Hempstead Unity Party", along with LaMont Johnson and Charles Renfroe, who were elected as trustees, defeating the incumbents in those positions.[48][49]

Education

Public schools

- The community is served by the Hempstead Union Free School District. Students attend Alverta B. Gray-Schultz Middle School and Hempstead High School for their secondary years of K-12 education.[50]

Private schools

- Sacred Heart Academy (all-girls; grades 9-12)[51]

Higher education

- Hofstra University[10]

The Mack Student Center at Hofstra University.

The Mack Student Center at Hofstra University.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 3.7 square miles (9.5 km2), all land.[52] The village of Hempstead differs from the majority of Nassau County as its population density is about 15,000 people per square mile—almost four times that of its neighbor on its northern border, Garden City, close to twice the density of Uniondale NY, its direct neighbor to the east, and about twice the density of Queens County, New York.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 2,316 | — | |

| 1880 | 2,521 | 8.9% | |

| 1890 | 4,831 | 91.6% | |

| 1900 | 3,582 | −25.9% | |

| 1910 | 4,964 | 38.6% | |

| 1920 | 6,382 | 28.6% | |

| 1930 | 12,650 | 98.2% | |

| 1940 | 20,856 | 64.9% | |

| 1950 | 29,135 | 39.7% | |

| 1960 | 34,641 | 18.9% | |

| 1970 | 39,411 | 13.8% | |

| 1980 | 40,404 | 2.5% | |

| 1990 | 49,453 | 22.4% | |

| 2000 | 56,554 | 14.4% | |

| 2010 | 53,891 | −4.7% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 55,113 | [5] | 2.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[53] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there were 53,891 people, 15,234 households, and 10,945 families residing in the village. The racial makeup of the village was 21.9% White, 44.2% Hispanic, 48.3% Black or African American, 0.6% Native American, 1.4% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 22.8% from other races, and 5.0% from two or more races.

There were 16,034 households, out of which 38.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.0% were married couples living together, 27.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.4% were non-families. 20.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 6.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.41 and the average family size was 3.76.[6]

In the village, the population was spread out, with 26.2% under the age of 18, 16.3% from 18 to 24, 31.4% from 25 to 44, 17.5% from 45 to 64, and 8.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.4 males.[6]

The median income for a household in the village was $45,234 and the median income for a family was $46,675. Males had a median income of $29,493 versus $27,507 for females. The per capita income for the village was $15,735. About 14.4% of families and 17.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.7% of those under age 18 and 16.9% of those age 65 or over.[6]

Fire department

The Village of Hempstead is protected by the firefighters of the Hempstead Fire Department.[54] The HFD currently operates out of 6 Fire Stations, located throughout the village, and 10 fire companies(Engine 1, Engine 2, Engine 3, Engine 4, Engine 5, Truck 1, Ladder 2, Hose 1, Hose 2, Hose 3). The HFD maintains a fire apparatus fleet of 8 Engines, 2 Trucks, 1 Rescue, and numerous other special, support, and reserve units. The HFD is part of Nassau County's Fire Department's 7th Battalion. As of September of 2020, the Hempstead Fire Department is commanded by a Chief of Department, Frederick V. Sandas, Jr.[54]

Fire station locations and apparatus

| Engine Company | Truck Company | Special Unit | Command Unit | Address | Neighborhood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engine 721, Engine 723 | Ambulance 7285A | 142 Jerusalem Ave. | Jerusalem Avenue | ||

| Engine 722 | Truck 7211 | Ambulance 7285 | Chief 7280, Chief 7281, Chief 7282, Chief 7283 | 75 Clinton St. | Downtown |

| Engine 724 | Rescue 7284 | 130 Jackson St. | Victory | ||

| Engine 725 | Floodlight 7287 | 108 Front St. | West End | ||

| Engine 726, Engine 728 | 10 Holly Ave. | East End | |||

| Engine 727 | Truck 7212 | 59 Long Beach Rd. | South Side |

Points of interest

- Hofstra University[10]

- Hofstra University Arboretum[10]

- Hempstead Bus Terminal[55]

- Nassau County African American Museum

- St. George's Episcopal Church

- Christ's First Presbyterian Church – First Presbyterian church established in the US

Transportation

The Rosa Parks Hempstead Transit Center is one of the largest hubs in Nassau County.[56] It serves as the terminus of the Long Island Rail Road's Hempstead Branch, and is served by a number of Nassau Inter-County Express routes.[56][57]

| Bus route

number |

Runs to / from | Notes |

| n6 |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| n6X | Express Service. | |

| n15 | ||

| n16 | ||

| n27 |

|

|

| n31 |

|

Via. West Broadway. |

| n32 |

|

Via. Broadway. |

| n35 | ||

| n40 | Via. North Main Street. | |

| n41 | Via. Babylon Turnpike. | |

| n43 | ||

| n48 |

|

Via. Carmans Road. |

| n49 |

|

Via. Newbridge Road. |

| n54 |

|

Via. Jerusalem Ave / Washington Ave. |

| n55 |

|

Via. Jerusalem Ave / Broadway. |

| n70 |

|

|

| n71 |

|

|

| n72 |

|

|

Notable people

Residents (native or lived) about whom an article exists, by date of birth:

- Hykiem Coney (1982 – 2006), anti-gang activist

- Samuel L. Mitchill (1764–1831), physician, naturalist and politic; born in Hempstead

- Walt Whitman (1819–1892; resident 1836–1838), poet, essayist, journalist, and humanist

- William S. Hofstra (1861–1932), entrepreneur

- Christopher Morley (1890–1957; resident during the 1910s), journalist, novelist, essayist, and poet

- Frank Field (b. 1923), television meteorologist

- Walter Hudson (1944–1991; life resident), 4th most obese human, Guinness World Record for the largest waist

- Julius Erving (born 1950), basketball star, lived in the village of Hempstead as a child for at least two or three years from around 1953 to 1955 or 1956[58]

- Sheryl Lee Ralph (born 1956), actress and singer

- Eric "Vietnam" Sadler (born 1960; native 1960-1987, music producer, Public Enemy, Ice Cube, Slick Rick, Bell Biv Devoe, Vanessa Williams, etc.)

- Rob Moore (born 1968; native), NFL football player

- Trevor Tahim "Busta Rhymes" Smith, Jr. (born 1972), resident, rapper, producer and actor

- Prodigy (1974–2017; native), member of hip-hop duo Mobb Deep

- Craig "Speedy" Claxton (born 1978; native), NBA basketball player

- Tavorris Bell (born 1978), former Harlem Globetrotter

- Scott Lipsky (born 1981), tennis player

- A+ (born 1982; native and childhood), rapper, made albums in 1996 and 1999 during his school years

The Hempstead Wall of Fame

The 2005 Wall of Fame Inductees are:

Ray Heatherton - the Merry Mailman

David Bythewood, Attorney, Grammy nominee and former Hempstead Public Schools Board of Education

|

The 2009 Wall of Fame Inductees are:

|

The Hempstead Wall of Fame is located in Kennedy Park off of Greenwich Street in Hempstead.

See also

References

- "Village Code of Village of Hempstead, NY". General Code. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- "About the Village". Incorporated Village of Hempstead. villageofhempstead.org. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "The Most Populous Counties and Incorporated Places in 2010 in New York: 2000 and 2010". U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- https://www.census.gov/search-results.html?q=Hempstead%2C+NY&page=1&stateGeo=none&searchtype=web&cssp=SERP&_charset_=UTF-8

- Bethany, Reine (2018). Hempstead Village. Foreword by Don Ryan. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1467128155. OCLC 1011679636.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Hempstead village, New York". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "Hofstra University | Long Island, New York". www.hofstra.edu. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- Costello, Alex. "Hempstead Town Hall Added to Registry of Historic Places." Long Island Patch, May 14, 2018, https://patch.com/new-york/gardencity/hempstead-town-hall-added-registry-historic-places

- Naylor, Natalie A., editor. The Roots and Heritage of Hempstead Town. Interlaken, NY: Heart of the Lakes Publishing, 1994. p. 15.

- McBride, Kevin. "Pequot War." Encyclopaedia Britannica, updated April 9, 2019.

- Strong, John. The Algonquian Peoples of Long Island from Earliest Times to 1700. Interlaken, NY: Empire State Books, 1997, pp. 144-150.

- Strong, John. The Algonquian Peoples of Long Island from Earliest Times to 1700. Interlaken, NY: Empire State Books, 1997, pp. 151-161.

- Naylor, Natalie A., editor. The Roots and Heritage of Hempstead Town. Interlaken, NY: Heart of the Lakes Publishing, 1994. pp. 15-16.

- Strong, John. The Algonquian Peoples of Long Island from Earliest Times to 1700. Interlaken, NY: Empire State Books, 1997, p. 33.

- Smits, Edward J. "New From Lange Eylandt: The 1640s and 1650s," in Natalie A. Naylor, ed., The Roots and Heritage of Hempstead Town. Interlaken, NY: Heart of the Lakes Publishing, 1994, p. 17.

- "History of Hempstead Village". Long Island Genealogy (James. B. York - Municipal Historian of Inc. Village of Hempstead). 1998. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- Schultz, Bernice. Colonial Hempstead. Lynbrook, New York: The Review-Star Press, 1937, pp. 11-12, 28.

- Hammell, George R. (Feb 1987). "Strawberries, Floating Islands, and Rabbit Captains: Mythical Realities and European Contact in the Northeast During the 16th and 17th Centuries". Journal of Canadian Studies. 21.

- Schultz, Bernice Marshall, 1937. Colonial Hempstead: Long Island Life Under the Dutch and English. Port Washington, NY: Ira J. Friedman. pp. 164-165 [Washington's visit] and 245-248 [Sammis Tavern history]

- Nevins, Allan. 1935. Abram S. Hewitt, with Some Account of Peter Cooper. New York: Harper and Brothers. p. 56.

- Nevins, pp. 57-58.

- Nevins, pp. 113-116.

- Bethany, Hempstead Village, p. 24.

- Naylor, Natalie A. (2005). "Hempstead (Town)". The Encyclopedia of New York State. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815608080. p. 707.

- "Nat Hicks". Society for Baseball Research. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- Morris, Peter (2003). Baseball Fever: Early Baseball in Michigan. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 322. ISBN 0-472-09826-8.

- "The Creation of Nassau County"- Published 1960, by the Nassau County Historical Museum

- "Camp Black – Garden City, Hemstead Plains 1898". Long Island Genealogy. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- "ON THE ROCKS: Christopher Morley's Harborside Retreat". Poetry Bay Online Poetry Magazine. 2003. Retrieved 2007-08-12.

- "About the Village". The Village of Hempstead Chamber of Commerce, New York. 2007. Archived from the original on 2004-06-11. Retrieved 2007-08-12.

- McQuiston, John T. (June 19, 1992). "A &S in Hempstead Closing After 40 Years". New York Times. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- "From the Desk of Mayor John Ryan - Week of October 1, 2018". Village of Hempstead, NY. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "Street named for LI's first African-American mayor". Newsday. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "LIRR Hempstead Station Hub Reconstruction Work Marked by Dedication Ceremony". Three Village Times. 1999-03-19. Archived from the original on 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

- "LI mayor on the mend after kidney transplant". Newsday. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "Hempstead Village gets new mayor as Don Ryan defeats Wayne Hall" (preview only; subscription required). Newsday. March 22, 2017. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- Pm, 2009 6:43. "Hempstead Village proposes illegal-rental crackdown". Newsday. Retrieved 2020-09-01.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Two alleged MS-13 members convicted of murder". Newsday. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- mfschjonberg (2017-04-04). "Trump's immigration policies force reduction of Episcopal Church's refugee resettlement network". Episcopal News Service. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

EMM receives very little money from the church-wide budget, instead receiving 99.5 percent of its funding from the federal government. Its main office is housed at the Episcopal Church Center in New York. Stevenson [Mark Stevenson, EMM's director] has said that 90 percent of the contract money directly goes to resettling refugees.

- "United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and Affiliates - Consolidated Financial Statements with Supplemental Schedules, December 31, 2016 & 2015 (With Independent Auditors' Report Thereon)" (PDF). www.usccb.org. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "Church World Service, Inc. Financial Statements, June 30, 2017 and 2016" (PDF). Church World Service. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "LONG ISLAND'S DEMOGRAPHIC DISPARITIES". www.mappinglidisparities.com. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

In 1968, the Fair Housing Act was signed into law by President Lyndon Baines Johnson (see image below). This bill would outlaw seller and landlord discrimination, hence protecting those buying or renting homes. However, many Long Island communities would remain segregated- some to this very day.

- "LONG ISLAND'S DEMOGRAPHIC DISPARITIES". www.mappinglidisparities.com. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- Carrozzo, Anthony (2019-11-17). "Undercover investigation reveals evidence of unequal treatment by real estate agents". Newsday. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "Hempstead Village's new mayor Don Ryan, trustees take office" (preview only; subscription required). Newsday. April 3, 2017. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- "Hempstead Unity Party Hempstead Unity Party: Meet the Candidtates" (2017). hempsteadunityparty.com. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- "Hempstead Union Free School District / Home". Hempstead UFSD. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "Explore Sacred Heart Academy". Niche. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Fire Department | Hempstead, NY". www.villageofhempstead.org. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "Rosa Parks Hempstead Transit Center". Newsday. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "Rosa Parks Hempstead Transit Center". Newsday. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- "Nassau Inter-County Express - Maps and Schedules". www.nicebus.com. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- Archived May 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Personal knowledge

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hempstead Village, New York. |