Ralph Cudworth

Ralph Cudworth FRS (/ˈreɪf ˈkʊdwɜːrθ/; 1617 – 26 June 1688) was an English Anglican clergyman, Christian Hebraist, classicist, theologian and philosopher, and a leading figure among the Cambridge Platonists.[1] From a family background embedded in the early nonconformist environment of Emmanuel College where he studied (1630–45), he became 11th Regius Professor of Hebrew (1645–88), 26th Master of Clare Hall (1645–54), and 14th Master of Christ's College (1654–88). He was a leading opponent of Thomas Hobbes's political and philosophical views, and his magnum opus was his The True Intellectual System of the Universe (1678).[2]

Ralph Cudworth | |

|---|---|

_(14597157587).jpg.webp) Ralph Cudworth | |

| Born | 1617 |

| Died | June 26, 1688 (aged 70–71) |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | University of Cambridge:

|

| Era | 17th-century philosophy Early modern philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Cambridge Platonists |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

| Ecclesiastical career | |

| Religion | Christianity (Anglican) |

| Church | Church of England |

| Ordained |

|

Offices held | Vicar, Great Wilbraham (1656) Rector, North Cadbury (1650–6) Rector, Toft (1656–62) Rector, Ashwell (1662–88) Prebendary, Gloucester (1678) |

Family background

Ancestry

Cudworth's family reputedly originated in Cudworth (near Barnsley), Yorkshire, moving to Lancashire with the marriage (c.1377) of John de Cudworth (d.1384) and Margery (d.1384), daughter of Richard de Oldham (living 1354), lord of the manor of Werneth, Oldham. The Cudworths of Werneth Hall, Oldham, were lords of the manor of Werneth/Oldham, until 1683. Ralph Cudworth (the philosopher)’s father, Ralph Cudworth (Snr) was the posthumous-born second son of Ralph Cudworth (d.1572) of Werneth Hall, Oldham.[3]

The Rev. Dr Ralph Cudworth Snr (1572/3–1624)

The philosopher's father, The Rev. Dr Ralph Cudworth (1572/3–1624), was educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he graduated BA (1592/93, MA (1596). Emmanuel College (founded by Sir Walter Mildmay (1584), and under the direction of its first Master, Laurence Chaderton) was, from its inception, a stronghold of Reformist, Puritan and Calvinist teaching, which shaped the development of puritan ministry, and contributed largely to the emigrant ministry in America.[4]

Ordained in 1599[5] and elected to a college fellowship by 1600,[6] Cudworth Snr was much influenced by William Perkins, whom he succeeded, in 1602, as Lecturer of the Parish Church of St Andrew the Great, Cambridge.[7] He was awarded the degree of Bachelor of Divinity in 1603.[8] He edited Perkins's Commentary on St Paul's Epistle to the Galatians (1604),[9] with a dedication to Robert, 3rd Lord Rich (later 1st Earl of Warwick), adding a commentary of his own with dedication to Sir Bassingbourn Gawdy.[10] Lord Rich presented him to the Vicariate of Coggeshall, Essex (1606)[11] to replace the deprived minister Thomas Stoughton, but he resigned this position (March 1608), and was licensed to preach from the pulpit by the Chancellor and Scholars of the University of Cambridge (November 1609).[12] He then applied for the Rectoriate of Aller, Somerset (an Emmanuel College living)[13] and, resigning his fellowship, was appointed to it in 1610.[14]

His marriage (1611) to Mary Machell (c.1582–1634), (who had been "nutrix" – nurse, or preceptor – to Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales)[15] brought important connections. Cudworth Snr was appointed as one of James I's chaplains.[16] Mary's mother (or aunt) was the sister of Sir Edward Lewknor, a central figure (with the Jermyn and Heigham families) among the puritan East Anglian gentry, whose children had attended Emmanuel College.[17] Mary's Lewknor and Machell connections with the Rich family included her first cousins Sir Nathaniel Rich and his sister Dame Margaret Wroth, wife of Sir Thomas Wroth of Petherton Park near Bridgwater, Somerset, influential promoters of colonial enterprise (and later of nonconformist emigration) in New England. Aller was immediately within their sphere.

Ralph Snr and Mary settled at Aller, where their children (listed below) were christened during the following decade.[18] Cudworth continued to study, working on a complete survey of Case-Divinity, The Cases of Conscience in Family, Church and Commonwealth while suffering from the agueish climate at Aller.[19] He was awarded the degree of Doctor of Divinity (1619),[20] and was among the dedicatees of Richard Bernard's 1621 edition of The Faithfull Shepherd.[21] Ralph Snr died at Aller declaring a nuncupative will (7 August 1624) before Anthony Earbury and Dame Margaret Wroth.[22]

Children

.jpg.webp)

The children of Ralph Cudworth Snr and Mary (née Machell) Cudworth (c.1582–1634) were:

- General James Cudworth (1612–82) was Assistant Governor (1756–8, 1674–80) and Deputy Governor (1681–2) of Plymouth Colony, Massachusetts, and four-times Commissioner of the United Colonies (1657–81),[23] whose descendants form an extensive family of American Cudworths.

- Elizabeth Cudworth (1615–54) married (1636) Josias Beacham of Broughton, Northamptonshire (Rector of Seaton, Rutland (1627–76)), by whom she had several children. Beacham was ejected from his living by the Puritans (1653), but reinstated (by 1662).[24]

- Ralph Cudworth (Jnr)

- Mary Cudworth

- John Cudworth (1622–75) of London and Bentley, Suffolk, Alderman of London, and Master of the Worshipful Company of Girdlers (1667–68).[25] On his death, John left four orphans of whom both Thomas Cudworth (1661–1726)[26] and Benjamin Cudworth (1670–15 Sept. 1725) attended Christ's College, Cambridge.[27] Benjamin Cudworth's black memorial slab is in St. Margaret's parish church, Southolt, Suffolk.

- Jane/Joan(?) Cudworth (b.c.1624; fl. unmarried, 1647) may have been Ralph's sister.[28]

Career

Education

The second son, and third of five (probably six) children, Ralph Cudworth (Jnr) was born at Aller, Somerset, where he was baptised (13 July 1617). Following the death of his father, Ralph Cudworth Snr (1624), The Rev. Dr John Stoughton (1593–1639), (son of Thomas Stoughton of Coggeshall; also a Fellow of Emmanuel College), succeeded as Rector of Aller, and married the widow Mary (née Machell) Cudworth (c.1582–1634).[29] Dr Stoughton paid careful attention to his stepchildren's education, which Ralph later described as a "diet of Calvinism".[30] Letters, to Stoughton, by both brothers James and Ralph Cudworth make this plain; and, when Ralph matriculated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge (1632),[31] Stoughton thought him "as wel grounded in Schol-Learning as any Boy of his Age that went to the University".[32] Stoughton was appointed Curate and Preacher at St Mary Aldermanbury, London (1632),[33] and the family left Aller. Ralph's elder brother, James Cudworth, married and emigrated to Scituate, Plymouth Colony, New England (1634).[34] Mary Machell Cudworth Stoughton died during summer 1634,[35] and Dr Stoughton married a daughter of John Browne of Frampton and Dorchester.[36]

Pensioner, Student and Fellow of Emmanuel College (1630–45)

A diligent student, Cudworth was admitted (as a pensioner) to Emmanuel College, Cambridge (1630), matriculated (1632), and graduated (BA (1635/6); MA (1639)). After some misgivings (which he confided in his stepfather),[37] he was elected a Fellow of Emmanuel (1639), and became a successful tutor, delivering the Rede Lecture (1641). He published a tract entitled The Union of Christ and the Church, in a Shadow (1642),[38] and another, A Discourse concerning the True Notion of the Lord's Supper (1642),[39] in which his readings of Karaite manuscripts (stimulated by meetings with Johann Stephan Rittangel) were influential.[40]

11th Regius Professor of Hebrew (1645) and 26th Master of Clare Hall (1645–54)

Following sustained correspondence with John Selden[41] (to whom he supplied Karaite literature), he was elected (aged 28) as 11th Regius Professor of Hebrew (1645).[42] In 1645, Thomas Paske had been ejected as Master of Clare Hall for his Anglican allegiances, and Cudworth (despite his immaturity) was selected as his successor, as 26th Master (but not admitted until 1650).[43] Similarly, his fellow-theologian Benjamin Whichcote was installed as 19th Provost of King's College.[44] Cudworth attained the degree of Bachelor of Divinity (1646), and preached a sermon before the House of Commons of England (on 1 John 2, 3–4),[45] which was later published with a Letter of Dedication to the House (1647).[46] Despite these distinctions and his presentation, by Emmanuel College, to the Rectoriate of North Cadbury, Somerset (3 October 1650), he remained comparatively impoverished. He was awarded the degree of Doctor of Divinity (1651),[47] and, in January 1651/2, his friend Dr John Worthington wrote of him, "If through want of maintenance he should be forced to leave Cambridge, for which place he is so eminently accomplished with what is noble and Exemplarily Academical, it would be an ill omen."[48]

Marriage (1654) and 14th Master of Christ's College (1654–88)

Despite his sight started worsening, Cudworth was elected (29 October 1654) and admitted (2 November 1654), as 14th Master of Christ's College.[49] His appointment coincided with his marriage to Damaris (d.1695), daughter (by his first wife, Damaris) of Matthew Cradock (d.1641), first Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Company. Hence Worthington commented "After many tossings Dr Cudworth is through God's good Providence returned to Cambridge and settled in Christ's College, and by his marriage more settled and fixed."[50]

In his Will (1641), Matthew Cradock had divided his estate beside the Mystic River at Medford, Massachusetts (which he had never visited, and was managed on his behalf)[51] into two moieties: one was bequeathed to his daughter Damaris Cradock (d.1695), (later wife of Ralph Cudworth Jnr); and one was to be enjoyed by his widow Rebecca (during her lifetime), and afterwards to be inherited by his brother, Samuel Cradock (1583–1653), and his heirs male.[52] Samuel Cradock's son, Samuel Cradock Jnr (1621–1706), was admitted to Emmanuel (1637), graduated (BA (1640–1); MA (1644); BD (1651)), was later a Fellow (1645–56), and pupil of Benjamin Whichcote.[53] After part of the Medford estate was rented to Edward Collins (1642), it was placed in the hands of an attorney; the widow Rebecca Cradock (whose second and third husbands were Richard Glover and Benjamin Whichcote, respectively), petitioned the General Court of Massachusetts, and the legatees later sold the estate to Collins (1652).[54][55]

The marriage of the widow Rebecca Cradock, to Cudworth's colleague Benjamin Whichcote laid the way for the union between Cudworth and her stepdaughter, Damaris (d.1695), thereby reinforcing the connections between the two scholars through a familial bond. Damaris had married, firstly (1642),[56] Thomas Andrewes Jnr (d.1653) of London and Feltham, son of Sir Thomas Andrewes (d.1659), (Lord Mayor of London, 1649, 1651–2), which union had produced several children. The Andrewes family were also engaged in the Massachusetts project, and strongly supported puritan causes.[57]

Commonwealth and Restoration

Cudworth emerged as a central figure among that circle of theologians and philosophers known as the Cambridge Platonists, who were (more or less) in sympathy with the Commonwealth: during the later 1650s, Cudworth was consulted by John Thurloe, Oliver Cromwell's Secretary to the Council of State, with regard to certain university and government appointments and various other matters.[58][59] During 1657, Cudworth advised Bulstrode Whitelocke's sub-committee of the Parliamentary "Grand Committee for Religion" on the accuracy of editions of the English Bible.[60] Cudworth was appointed Vicar of Great Wilbraham, and Rector of Toft, Cambridgeshire Ely diocese (1656), but surrendered these livings (1661 and 1662, respectively) when he was presented, by Dr Gilbert Sheldon, Bishop of London, to the Hertfordshire Rectory of Ashwell (1 December 1662).[61]

Given Cudworth's close cooperation with prominent figures in Oliver Cromwell's regime (such as John Thurloe), Cudworth's continuance as Master of Christ's was challenged at the Restoration but, ultimately, he retained this post until his death.[62] He and his family are believed to have resided in private lodgings at the "Old Lodge" (which stood between Hobson Street and the College Chapel), and various improvements were made to the College rooms in his time.[63]

Later life

In 1665, Cudworth almost quarrelled with his fellow-Platonist, Henry More, because of the latter's composition of an ethical work which Cudworth feared would interfere with his own long-contemplated treatise on the same subject.[64] To avoid any difficulties, More published his Enchiridion ethicum (1666–69), in Latin;[65] However, Cudworth's planned treatise was never published. His own majestic work, The True Intellectual System of the Universe (1678),[66] was conceived in three parts of which only the first was completed; he wrote: "there is no reason why this volume should therefore be thought imperfect and incomplete, because it hath not all the Three Things at first Designed by us: it containing all that belongeth to its own particular Title and Subject, and being in that respect no Piece, but a Whole."[67]

Cudworth was installed as Prebendary of Gloucester (1678).[68] His colleague, Benjamin Whichcote, died at Cudworth's house in Cambridge (1683),[69] and Cudworth himself died (26 June 1688), and was buried in the Chapel of Christ's College.[70] An oil portrait of Cudworth (from life) hangs in the Hall of Christ's College.[71] During Cudworth's time an outdoor Swimming Pool was created at Christ's College (which still exists), and a carved bust of Cudworth there accompanies those of John Milton and Nicholas Saunderson.[72]

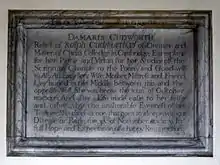

Cudworth's widow, Damaris (née Cradock) Andrewes Cudworth (d.1695), maintained close connections with her daughter, Damaris Cudworth Masham, at High Laver, Essex, which was where she died, and was commemorated in the church with a carved epitaph reputedly composed by the philosopher John Locke.[73]

Children

The children of Ralph Cudworth and Damaris (née Cradock) Andrewes Cudworth (d.1695) were:

- John Cudworth (c.1656–1726) was admitted to Christ's College, Cambridge (1672), graduated (BA (1676–7); MA (1680)), and was a pupil of Mr Andrewes. He was a Fellow (1678–98), was ordained a priest (1684), and later became Lecturer in Greek (1687/8) and Senior Dean (1690).[74]

- Charles Cudworth (d.1684) was admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge (1674–6), but may have not graduated, instead, making a career in the factories of Kasimbazar, West Bengal, India, which was where John Locke (friend of his sister Damaris Cudworth), corresponded with him (27 April 1683).[75] He married (February 1683/84), Mary Cole, widow of Jonathan Prickman, Second for the English East India Company at Malda.[76] Charles Cudworth died in March 1684.[77]

- Thomas Cudworth graduated at Christ's College, Cambridge (MA (1682)).[78][79]

- Damaris Cudworth (1659–1708), a devout and talented woman, became the second wife (1685) of Sir Francis Masham, 3rd Baronet (c.1646–1723) of High Laver, Essex.[80] Lady Masham was a friend of the philosopher John Locke, and also a correspondent of Gottfried Leibniz. Her son, Francis Cudworth Masham (d.1731), became Accountant-General to the Court of Chancery.

The stepchildren of Ralph Cudworth (children of Damaris (née Cradock) Andrewes (d.1695) and Thomas Andrewes (d.1653) were:

- Richard Andrewes (living 1688) who, according to Peile, is not the Richard Andrewes who attended Christ's College, Cambridge during this period.[81]

- John Andrewes (d. after 1688?) matriculated at Christ's College, Cambridge (1664), graduated (BA (1668/9); MA (1672)), was ordained deacon and priest (1669–70), and was a Fellow (1669–75).[82] Peile suggests he died c.1675, but he was a legatee in the will of his brother Thomas (1688). John Covel attended a "Pastoral" performed by Cudworth's children contrived by John Andrewes.[83]

- Thomas Andrewes (d.1688), Citizen and Dyer of London, was a linen draper. He married (August 1681), Anna, daughter of Samuel Shute, of St Peter's, Cornhill.[84][85]

- Mathew Andrewes (d.1674) was admitted to Queens' College, Cambridge (1663/4), and later elected a Fellow.[86]

- Damaris Andrewes (d.1687) married (1661), (as his first wife) Sir Edward Abney (1631–1728), (a student at Christ's College, Cambridge (BA 1649–52/53); Fellow (1655–61); and Doctor of both laws (1661)).[87][88]

Works

Sermons and Treatises

Cudworth's works included The Union of Christ and the Church, in a Shadow (1642); A Sermon preached before the House of Commons (1647); and A Discourse concerning the True Notion of the Lord's Supper (1670). Much of Cudworth's work remains in manuscript. However, certain surviving works have been published posthumously, such as A Treatise concerning eternal and immutable Morality, and A Treatise of Freewill.

A Treatise concerning eternal and immutable Morality (posth.)

Cudworth's Treatise on eternal and immutable Morality, published with a preface by Edward Chandler (1731),[89] is about the historical development of British moral philosophy. It answers, from the standpoint of Platonism, Hobbes's famous doctrine that moral distinctions are created by the state: just as knowledge contains a permanent intelligible element over and above the flux of sense-impressions, so there exist eternal and immutable ideas of morality. Cudworth's ideas (like those of Plato) have "a constant and never-failing entity of their own" (such as we see in geometrical figures); but, unlike Plato's ideas, they exist in the mind of God, whence they are communicated to finite understandings. Hence "it is evident that wisdom, knowledge and understanding are eternal and self-subsistent things, superior to matter and all sensible beings, and independent upon them"; and so also are moral good and evil. Cudworth does not attempt to give any list of Moral Ideas. It is, indeed, the cardinal weakness of this form of intuitionism that no satisfactory list can be given, and that no moral principles have the "constant and never-failing entity" (or the definiteness) of the concepts of geometry (these attacks are not uncontested — for example, see "Common Sense" tradition from Thomas Reid to James McCosh and the Oxford Realists Harold Prichard and Sir William David Ross). Henry More's Enchiridion ethicum, attempts to enumerate the "noemata moralia"; but, so far from being self-evident, most of his moral axioms are open to serious controversy.

A Treatise of Freewill (posth.)

Another posthumous publication was Cudworth's A Treatise of Freewill, edited by John Allen (1838). Both this and the Treatise on eternal and immutable Morality are connected with the design of his magnum opus, The True Intellectual System of the Universe.[90]

The True Intellectual System of the Universe (1678)

In 1678, Cudworth published The True Intellectual System of the Universe: the first part, wherein all the reason and philosophy of atheism is confuted and its impossibility demonstrated, which had been given an Imprimatur for publication (29 May 1671).

.jpg.webp)

The Intellectual System arose, so Cudworth informs us, from a discourse refuting "fatal necessity", or determinism.[91] Enlarging his plan, he proposed to prove three matters:

- (a) the existence of God;

- (b) the naturalness of moral distinctions; and

- (c) the reality of human freedom.

These three comprise, collectively, the intellectual (as opposed to the physical) system of the universe; and they are opposed, respectively, by three false principles: atheism, religious fatalism (which refers all moral distinctions to the will of God), and the fatalism of the ancient Stoics (who recognized God and yet identified Him with nature). The immense fragment dealing with atheism was all that was published, perhaps because of the theological clamour raised against this first part.

Cudworth criticizes two main forms of materialistic atheism: the atomic (adopted by Democritus, Epicurus and Hobbes); and the hylozoic (attributed to Strato of Lampsacus, which explains everything by the supposition of an inward self-organizing life in matter). Atomic atheism is by far the more important, if only because Hobbes (the great antagonist whom Cudworth always has in view), is supposed to have held this view. It arises from the combination of two principles, neither of which is, individually, atheistic (namely atomism and corporealism (or the doctrine that nothing exists but body)). The example of Stoicism, as Cudworth suggests, shows that corporealism may be theistic.

Cudworth plunges into the history of atomism with vast erudition.[92] It is, in its purely physical application (a theory that he fully accepts), he holds that atomism was taught by Pythagoras, Empedocles (and, in fact, nearly all the ancient philosophers), and was only perverted to atheism by Democritus. Cudworth believes that atomism was first invented before the Trojan war by a Sidonian thinker named Moschus or Mochus (identical with Moses in the Old Testament). In dealing with atheism, Cudworth's method was to marshal the atheistic arguments elaborately, so elaborately that Dryden remarked "he has raised such objections against the being of a God and Providence that many think he has not answered them"; then, in his last chapter (which, by itself, is the length of an ordinary treatise), he confutes the arguments with all the reasons that his reading could supply. A subordinate matter in the book which attracted much attention at the time was the conception of the "Plastic Medium" (a mere revival of Plato's "World-Soul," which is intended to explain the existence and laws of nature without referring to the direct operation of God), which occasioned a long-drawn controversy, between Pierre Bayle and Le Clerc (the former maintaining; the latter denying), that the Plastic Medium is favourable to atheism.

Commentary on Cudworth

Andrew Dickson White wrote in his A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896):

In 1678 Ralph Cudworth published his Intellectual System of the Universe. To this day he remains, in breadth of scholarship, in strength of thought, in tolerance, and in honesty, one of the greatest glories of the English Church... He purposed to build a fortress which should protect Christianity against all dangerous theories of the universe, ancient or modern. ...while genius marked every part of it, features appeared which gave the rigidly orthodox serious misgivings. From the old theories of direct personal action on the universe by the Almighty he broke utterly. He dwelt on the action of law, rejected the continuous exercise of miraculous intervention, pointed out the fact that in the natural world there are "errors" and "bungles" and argued vigorously in favor of the origin and maintenance of the universe as a slow and gradual development of Nature in obedience to an inward principle.

Arms

|

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Ralph Cudworth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- J.A. Passmore, Ralph Cudworth: An Interpretation (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1951).

- D.A. Pailin, 'Cudworth, Ralph (1617–88)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004).

- Edwin Butterworth, Historical Sketches of Oldham (John Hirst: Oldham, 1856), pp. 22–23 (Google); 'Pedigree of the Families of Oldhams and Cudworths' in James Butterworth, History and Description of the Parochial Chapelry of Oldham (J. Dodge, etc: Oldham, 1826), pp. 52ff.; Thomas Fuller, History of the Worthies of England, ed. T.A. Nuttall (Thomas Tegg: London, 1811), ii, p. 208 (Internet Archive); R.E. Stansfield-Cudworth, 'Gentry, Gentility, and Genealogy in Lancashire: The Cudworths of Werneth Hall, Oldham, c.1377-1683', Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society, 111 (2019), 48–80.

- 'History of the College' Emmanuel College website; S. Bendell, C. Brooke, and P. Collinson, A History of Emmanuel College (Boydell Press: Woodbridge 1999).

- Church of England clergy database, Ordination record: ID 123517. Person Record CCEd ID 89100.

- S. Bush Jnr and C.J. Rasmussen, The Library of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, 1584–1637 (Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 77–79 and p. 210 (Google).

- B. Carter, 'The standing of Ralph Cudworth as a Philosopher' in G.A.J. Rogers, T. Sorell, and J. Kraye (eds), Insiders and Outsiders in Seventeenth Century Philosophy (Routledge: London, 2009), at p. 100 (see note 4).

- Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses i(1), p. 431.

- H.C. Porter, Reformation and Reaction in Tudor Cambridge (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1958), pp. 264–66 (Google)

- A Commentarie or Exposition, upon the Five First Chapters of the Epistle to the Galatians: penned by the godly, learned, and iudiciall divine, Mr. W. Perkins. Now published for the benefit of the Church, and continued with a supplement upon the sixt chapter, by Rafe Cudworth Bachelour of Divinitie (John Legat: London, 1604).

- Clergy of the Church of England database, CCEd Appointment Record ID: 193664.

- Church of England clergy database, CCEd Records ID: 193711 (Vacancy), and 178652 (Appointment).

- R.W. Dunning (ed.), 'Parishes: Aller ', A History of the County of Somerset, iii (1974), pp. 61–71 (British History Online).

- CCEd Appointment Evidence Record ID: 178651, as 30 August 1610.

- J.L. v. Mosheim, Radulphi Cudworthi Systema intellectuale hujus universi (sumtu viduae Meyer: Jena, 1733), i, 'Praefatio Moshemii' (34 sides, unpaginated), side 19. The information was from Edward Chandler.

- Mosheim, as cited above.

- P. Collinson, '17: Magistracy and Ministry – A Suffolk Miniature', in Godly People. Essays on English Protestantism and Puritanism (Hambledon Press: London, 1983), pp. 445–66.

- D. Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry, ed. K.J. Everingham, 2nd Edn (2011), ii, p. 10, items 15–16)

- Letter of Ralph Cudworth (Snr) to James Ussher, Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Rawlinson Letters 89, fol. 25 r–v: Early modern letters online.

- Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses.

- R. Bernard, The Faithfull Shepherd, wholy in a manner transposed, 3rd Edn, Thomas Pavier: London, 1621), dedication in front matter (Internet Archive). (1st Edition, 1607, 2nd 1609).

- Will of Raphe Cudworthe, Doctor of Divinity, Parson of Aller, Somerset (P.C.C. 1624, Byrde quire).

- Samuel Deane, 'Gen. James Cudworth' in History of Scituate, Massachusetts, from its first settlement to 1831 (James Loring: Boston, 1831), pp. 245–51; also Scituate Historical Society Archived 24 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Josias Beacham’s first wife was Maria Sheffield (d.1634): S.H.C., 'Extracts from the Parish register of Seton, Co. Rutland, relative to the family of Sheffield', Collectanea Topographica et Genealogica I (J.B. Nichols & Son: London, 1834), pp. 171–73.; Will of Josias Beacham, Rector of Seaton (Rutland) (P.C.C. 1675/76). London Marriage Allegations, 28 April 1636 (St Mary Aldermanbury). Foster, Index Ecclesiasticus. Beacham was a graduate of Brasenose College, Oxford

- W. Dumville Smythe, An Historical Account of the Worshipful Company of Girdlers, London (Chiswick Press: London, 1905), pp. 109–10.; Will of John Cudworth, Girdler of London (P.C.C. 1675).

- J. Peile, Biographical Register of Christ's College, 1505–1905: II: 1666–1905 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1913), p. 64 (Internet Archive).

- J. Peile, Biographical Register, ii, p. 111.

- D. Richardson, Jewels of the Crown, 4 (2009), citing references to Jane Cudworth in the Will of John Machell of Wonersh (P.C.C. 1647).

- J.C. Whitebrook, 'Dr. John Stoughton the Elder', Transactions of the Congregational Historical Society, 6(2), (1913), pp. 89–107; and 6(3), (1914), pp. 177–87 (Internet Archive).

- F.J. Powicke, The Cambridge Platonists: A Study (J.M. Dent & Co.: London, 1926), p. 111.

- "Cudworth, Ralph (CDWT632R)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.. See Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses i(1), p. 431.

- Mosheim, Radulphi Cudworthi Systema Intellectuale (1733), i, 'Praefatio Moshemii' (34 sides, unpaginated) 19th side, note.

- Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses, i(4), p. 171.

- 'Letter of James Cudworth of Scituate, 1634', (to Stoughton), in New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 14 (1860), pp. 101–04.

- Whitebrook, 'Dr John Stoughton the Elder', p. 94 (Internet Archive).

- Marriage at St Mary Aldermanbury, 18 January 1635/6; J.P. Ferris, Browne, John II (1580–1659), of Dorchester and Frampton, Dorset, History of Parliament online, 1604–29.

- T. Solly, The Will Divine and Human (Deighton Bell & Co.: Cambridge/Bell & Daldy: London, 1856), pp. 287–91.

- R. Cudworth, The Union of Christ and the Church, in a Shadow (Richard Bishop: London, 1642) (Umich/eebo).

- R. Cudworth, A Discourse concerning the True Notion of the Lord's Supper (2nd edn, J. Flesher for R. Royston: London, 1670) (Google).

- D.J. Lasker, 'Karaism and Christian Hebraism: a New Document', Renaissance Quarterly, 59(4), (2006), pp. 1089–1116.

- D. Levitin, Ancient Wisdom in the Age of the New Science: Histories of Philosophy in England, c.1640–1700 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2015), p. 171 and note 300, with itemized citations (Google).

- Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses.

- D. Neal (ed. J.O. Choules), The History of the Puritans, or Protestant Nonconformists (Harper & Brothers: New York, 1844), p. 481 (Google). See J. Barwick, Querela Cantabrigiensis (Oxford 1647), 'A Catalogue' (Umich/eebo).

- S. Hutton, 'Whichcote, Benjamin (1609–83), theologian and moral philosopher' in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- New King James Version at Bible Gateway

- R. Cudworth, A sermon preached before the Honourable House of Commons, at Westminster, March 31. 1647 (Roger Daniel: Cambridge, 1647), Letter of Dedication (Umich/eebo).

- Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses.

- Letter of John Worthington (6 January 1651/2), quoted in Mosheim's Preface to Systema Intellectuale (1733), i, p. xxviii (1773 edn).

- '1654, Oct. 29. Dr Cudworth was chosen Master of Christ's College, admitted Nov. 2.': J. Crossley, Diary and Correspondence of Dr John Worthington (Chetham Society, O.S., 13 (1847), i, p. 52.

- Letter of John Worthington (30 January 1654/5) quoted in Mosheim's Preface (1733), i, p. xxviii (1773 edn)

- C. Seaburg and A. Seaburg, Medford on the Mystic (Medford Historical Society, 1980).

- Will of Mathew Cradock of London, Merchant (P.C.C. 1641); C. Brooks, The History of the Town of Medford (J.M. Usher: Boston, 1855), pp. 90–92 (Internet Archive).

- Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses, i(1), p. 411; J.C. Whitebrook, 'Samuel Cradock, cleric and pietist (1620–1706): and Matthew Cradock, first governor of Massachusetts', Congregational History Society, 5(3), (1911), pp. 183–90; S. Handley, 'Cradock, Samuel (1620/21–1706), nonconformist minister', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Brooks, The History of the Town of Medford, pp 41–43, and p. 93 (Internet Archive).

- 'Cradock, Craddock', in C.H. Pope, The Pioneers of Massachusetts: A Descriptive List (Boston 1900), pp. 121–22 (Internet Archive).

- R. Brenner, Merchants and Revolution: Commercial Change, Political Conflict, and London's Overseas Traders, 1550–1663 (Verso: London, 2003), p. 139 (Google).

- Will of Thomas Andrewes, Leather seller of London (P.C.C. 1653). These relationships are confirmed by these wills and the Chancery case Andrewes v Glover (National Archives, London); W.G. Watkins, 'Notes from English Records', New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 64 (1910), pp. 84–87.

- T. Birch, Account of the Life and Writings (1743), pp. viii–x (pp. 16–18 in pdf).

- 'Life of Cudworth, Appendix A: Letters to Thurloe', in W.R. Scott, An Introduction to Cudworth's Treatise concerning Eternal and Immutable Morality (Longmans, Green & Co.: London, 1891), pp. 19–23 (Hathi Trust).

- C. Anderson, The Annals of the English Bible (William Pickering: London, 1845), ii, Book 3, p. 394 (Google).

- Clergy of the Church of England database.

- Letter (6 August 1660), in J. Crossley, Diary and Correspondence of Dr John Worthington (Chetham Society, O.S., 13 (1847)), i, p. 203; and Christ's College website, List of Masters of Christ's College.

- J. Covell, 'An Account of the Master's Lodgings in ye College', in R. Willis and J.W. Clarke, The Architectural History of the University of Cambridge, and of the Colleges of Cambridge and Eton, (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1886), ii, pp. 212–19 (Internet Archive).

- 'Life of Cudworth, Appendix B: Letters of Cudworth and More', in Scott, An Introduction to Cudworth's Treatise, pp. 24–28 (Hathi Trust).

- An Account of Virtue; or, Dr. Henry More's Abridgement of Morals, put into English (transl. Edward Southwell), (facsimile of Benjamin Tooke's London (1690) English edn; Facsimile Text Society, New York, 1930), Internet Archive.

- R. Cudworth, The True Intellectual System of the Universe: The First Part; Wherein, All the Reason and Philosophy of Atheism is Confuted, and its Impossibility Demonstrated (Richard Royston: London, 1678)

- R. Cudworth, 'Preface to the Reader', True Intellectual System (1678).

- Clergy of the Church of England database.

- G. Dyer, History of the University and Colleges of Cambridge, (Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown: London, 1814), ii, p. 355 (Google).

- Epitaph in Mosheim's Preface (1733), i, p. xxix (1773 edn); for his monumental inscription .

- Oil portrait of Ralph Cudworth, image (copyright Christ's College) viewable here.

- 'Splashing out for a piece of history', News, 23 July 2010 (University of Cambridge website). Listing by Historic England.

- Will of Damaris Cudworth (P.C.C. 1695); H.R. Fox Bourne, The Life of John Locke, (Harper & Brothers: New York, 1876), ii, pp. 306–07 (Internet Archive).

- J. Peile, Biographical Register of Christ's College 1505–1905: II: 1666–1905 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1913), ii, p. 46.

- Locke's letter, in Lord King, The Life of John Locke: With Extracts from His Correspondence (New Edn, Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley: London, 1830), ii, pp. 16–21 (Google).

- R.C. Temple, The Diaries of Streynsham Master, 1675–80, and other contemporary papers relating thereto II: The First and Second "Memorialls, 1679–80, Indian Records Series (John Murray: London, 1911), p. 343 and note 2 (Internet Archive); W.K. Firminger (ed.), 'The Malda Diary and Consultations (1680–82)', Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, N.S., 14 (1918), pp. 1–241 (Internet Archive).

- J. Peile, Biographical Register, ii, pp. 49–50, citing Journal entries from Factory Records, Kasinbazar III.

- J. Peile, Biographical Register, ii, p. 70.

- Locke's letter supposedly addressed to Thomas, in H.R. Fox Bourne, The Life of John Locke (Harper and Brothers: New York, 1876), i, pp. 473–76 (Internet Archive).

- M. Knights, 'Masham, Sir Francis, 3rd Bt. (c. 1646–1723), of Otes, High Laver, Essex', in D. Hayton, E. Cruickshanks, and S. Handley (eds), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons, 1690–1715 (Boydell & Brewer,Woodbridge, 2002), History of Parliament Online.

- J. Peile, Biographical Register, I: 1448–1665 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1910), i,p. 601 (Internet Archive).

- Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses, i(1), p. 30; J. Peile, Biographical Register, i, p. 612 (Internet Archive).

- Covell, 'An Account of the Master's Lodgings'.

- G.J. Armytage, Allegations for Marriage-Licences Issued by the Vicar-General of the Archbishop of Canterbury, July 1679 to June 1687, Harleian Society, 30 (1890), p. 70 (Internet Archive).

- Will of Thomas Andrewes, Citizen and Dyer of London (P.C.C. 1688, Foot quire); H.F. Waters, Genealogical Gleanings in England, with the addition of New Series, A-Anyon (Genealogical Publishing Company: Baltimore, 1969), ii, pp. 1738–39 (Internet Archive).

- Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses, i(1), p. 30. Will of Mathew Andrewes, Fellow of Queen's College, Cambridge (P.C.C. 1674, Bunce quire); H.F. Waters, Genealogical Gleanings in England, with the addition of New Series, A-Anyon (Genealogical Publishing Company: Baltimore, 1969), ii, p. 1738.

- Venn, Alumni Cantabrigienses, i(1), p. 2; A.A. Hanham, 'Abney, Sir Edward (1631–1728), of Willesley Hall, Leics. and Portugal Row, Lincoln’s Inn Fields', in D. Hayton, E. Cruickshanks, and S. Handley (eds), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1690–1715 ( Boydell and Brewer: Woodbridge, 2002), History of Parliament Online.

- For correspondence between Cudworth and Edward's father, James Abney: E. Randall (ed.), C. Melinsky (ill.), Letters to my Father: Edward Abney, 1660–63 (Simon Randall: Sevenoaks, 2005).

- R. Cudworth, Treatise Concerning Eternal and Immutable Morality... with a Preface by... Edward Lord Bishop of Durham (1st edn, James and John Knapton: London, 1731)

- S. Hutton (ed), Ralph Cudworth, A Treatise Concerning Eternal and Immutable Morality with A Treatise of Freewill (Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1996). Read here

- H. Sturt, 'Cudworth, Ralph (1617–88), English philosopher', Encyclopedia Britannica, vii (1910), pp. 612–13.

- See a recent study by Catherine Osborne, 'Ralph Cudworth's The True Intellectual System of the Universe and the Presocratic Philosophers', in O. Primavesi and K. Luchner (eds), The Presocratics from the Latin Middle Ages to Hermann Diels (Steiner Verlag, 2011), pp. 215–35.

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cudworth, Ralph". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 612–613.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cudworth, Ralph". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 612–613.

Further reading

- Cudworth's The True Intellectual System of the Universe (1678) was translated into Latin by Johann Lorenz von Mosheim, and furnished with notes and dissertations translated into English in John J. Harrison's edition (1845). The first Latin edition: Johann Lorenz von Mosheim, Radulphi Cudworthi Systema intellectuale hujus universi, 2 Vols (sumtu viduae Meyer, Jena 1733); the second Latin edition (with paginated Mosheimii Praefatio): (Samuel and John Luchtmans: Lugduni Batavorum, 1773).

- Thomas Birch's Account (biography), first published (1743) in the Second Edition (London), and reprinted in subsequent editions. Birch supplied notes and references to Cudworth's text, after Mosheim.

- Paul Alexandre René Janet, Essai sur le médiateur plastique de Cudworth (Ladrange: Paris, 1860).

- John Tulloch, Rational theology and Christian Philosophy in England in the seventeenth century (William Blackwood and Sons: Edinburgh and London, 1874), ii, pp. 193–302.

- C.E. Lowrey, The Philosophy of Ralph Cudworth: a study of the True Intellectual System of the Universe (Phillips & Hunt: New York, 1884).

- James Martineau, Types of Ethical Theory (Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1885), ii, pp. 396–424.

- William Richard Scott, An Introduction to Cudworth's Treatise (Longmans, Green & Co.: London, 1891).

- Slawomir Raube, Deus explicatus: Stworzenie i Bóg w myśli Ralpha Cudwortha (Creation and God in Ralph Cudworth’s Thought) (Bialystok (Poland), 2000).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ralph Cudworth |

- Cambridge Platonists’ Research Group: Research Portal: Ralph Cudworth Bibliography

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- H. Sturt, 'Cudworth, Ralph (1617–1688)',

- Article on Cudworth in Treasures in Focus Blog, Christ's College, Cambridge No. 8, July 2013.

- "Cudworth, Ralph". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Klaus-Gunther Wesseling (1999). "Cudworth {der Jüngere}, Ralph". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). 16. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 352–362. ISBN 3-88309-079-4.

- R. Cudworth, The True Intellectual System of the Universe (1678) on Google Books

- R. Cudworth, The True Intellectual System of the Universe (1678; 3-volume edn: Tegg, 1845) on Internet Archive: Volume 1, Volume 2, and Volume 3.

- R. Cudworth, Sermon before the Commons, at Westminster, 31 March 1647 (1647; repr. 1852)

- R. Cudworth, A Treatise concerning Eternal and Immutable Morality (1731)

- R. Cudworth, They know Christ who keep his Commandments (repr. 1858)

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Thomas Paske vacancy from 1645 |

Master of Clare College, Cambridge 1650–1654 |

Succeeded by Theophilus Dillingham |

| Preceded by Samuel Bolton |

Master of Christ's College, Cambridge 1654–1688 |

Succeeded by John Covel |