History of Medieval Cumbria

The history of medieval Cumbria has several points of interest. The region's status as a borderland coping with 400 years of warfare is one. The attitude of the English central government, at once uninterested and deeply interested, is another. As a border region, of geopolitical importance, Cumbria changed hands between the Angles, Norse (Norwegians, Danes and Hiberno-Norse), Strathclyde Brythons, Picts, Normans, Scots and English; and the emergence of the modern county is also worthy of study.

Early Medieval Cumbria, 410–1066

After the Romans: warring tribes and the Kingdom of Rheged, c. 410–600

By the official Roman break with Britannia in 410, most of the parts of Britain which had been formerly occupied by them were already effectively independent of the empire. In Cumbria, the Roman presence had been almost entirely military rather than civil, and the withdrawal is unlikely to have caused much change. Many of the Roman forts may have continued in use as places of local government and habitation; there is evidence suggesting that Birdoswald was inhabited until at least the 6th century, for example. However, many questions remain as to what post-Roman Cumbria looked like, in terms of its political and social life.

Sources – history and legend

The questions mentioned above remain to be answered because now we enter the period that used to be called the Dark Ages, due to the lack of archaeological and paleobotanical finds, and the unreliability of the documentary sources that we are forced to use as a result (although the last few decades have provided more in the way of archaeological evidence due to the improvement in dating, especially by means of radiocarbon analysis).[1] Some historians, therefore, dismiss some well-known figures of the 5th and 6th centuries, potentially connected with Cumbria, as being legendary or -pseudo-historical. Higham, for example,[2] consigns to this category such people as King Arthur, Cunedda (due to the unreliability of the 9th-century source, the Historia Brittonum), and Coel Hen (due to the unreliability of the source known as the Harleian genealogies). He argues that we are left with the not un-biased source, the De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae of Gildas, as well as an oral and poetic tradition that includes the work of Taliesin and Aneirin, as much, if not more, literary works than historical ones. The information gleaned from all of these sources may not necessarily be factually incorrect, but in terms of the standard expected of historical verifiability, they fall short.

Arthur and Cumbria

As far as Arthur is concerned, as with many other areas with Celtic connections, there are a number of Arthurian legends associated with Cumbria.[3] Arthur's father Uther Pendragon is supposed to have lived at Pendragon Castle, high in the upper Eden Valley, although the castle itself is probably 12th century and was originally called Mallerstang Castle. It is likely that Robert de Clifford, 1st Baron de Clifford, joining in with the Arthurian obsession of the time, as well as pointing to his Welsh forebears, assumed the name of Uther Pendragon and renamed the existing castle to fit in with the cult.[4] King Arthur's Round Table, a prehistoric earthwork near Penrith, has no actual associations with Arthur but is said to have been a duelling ground for Lancelot. It, too, was near Clifford's castle at Brougham and was probably given the name by him.[5]

It was also believed that Arthur's last battle at Camlann, in which he was fatally wounded, was fought near the fort of Birdoswald, whose Roman name was thought to have been Camboglanna (although it is now thought that Birdoswald was really called Banna, with Castlesteads being Camboglanna).[6] The Roman bath-house at Ravenglass, known locally as Walls Castle, was thought to be the Arthurian Lyons Garde, or Taliesin's Caer sidi or Avalon where Arthur was taken after the battle.[7]

More popular in local legend are associations with Arthur's knight Gawain, who is linked with Tarn Wadling, now a dried up lake near High Hesket (and overlooked by Owain mab Urien's Castle Hewen). The source of this romance is The Awntyrs off Arthure at the Terne Wathelyne, written in the 14th century, probably by someone local.[8]

There is some validation of a " mansion house of King Arthur" in Carlisle to be found in a charter of Henry II confirming another charter of Henry I. This latter charter grants 'land which was around Arthur's burh in Carlisle, next to the house of the canons'. If nothing else, this reference shows that the linking of Arthur's stronghold to Carlisle dates back to the early 12th century, well before the later Arthurian romances were written.[9]

Warring tribes

Even before the Romans left Britain, Welsh tradition has it that Coel Hen was an important figure in the Roman province of Northern Britain, which covered everything between the River Humber and the River Tweed. He is seen as the last Dux Britanniarum ("leader of the Britons") and as such would have commanded the army in this region, with there being no great abandonment of Hadrian's Wall. After the withdrawal, Coel Hen became the High King of Northern Britain (in the same vein as the Irish Ard Rí) and ruled, supposedly, from Eboracum (now York). This scenario is doubted by historians who are given to think that the Welsh genealogical tracts which mention Coel were later, 9th century, attempts to bolster Brythonic history against the encroaching English. There is "scant archaeological evidence for continuity" of Roman garrisons in the north.[10]

It is probably safer to say that successive withdrawals of Roman troops from Cumbria throughout the 4th and early 5th centuries created a power vacuum which, by necessity, was filled by local warlords and their followers, often just based around a single village or valley. After the withdrawal of Stilicho in 401, the troops on the Wall were barely able to confront the raids of the barbarians to the north. These raids, as in the 360s, concentrated on the capturing of cattle and slaves, and they were seen off by the local communities themselves, so that by around 450, after the Third Pictish War, the Scots had withdrawn to Ireland and the Picts had left for Scotland north of the Forth.[11]

Until the early-to-mid 500s, Gildas reports only occasional raiding from outside the Cumbrian area. The main strife of this period was created by the local 'tyrants', or warlords, fighting amongst themselves, raiding and defending themselves against raids. The raids again concentrated on the stealing of goods, mainly cattle and slaves – slaving becoming an international market at this time as coinage was non-existent (Saint Patrick was one of these captured slaves, possibly taken by Irish pirates in the Irthing valley or possibly at Ravenglass).

Local 'kings', with successors, were continually being made and unmade in this intertribal warfare, and by the end of the 6th century some had gained a lot of power and had formed kingships over a larger area. One of these was Coroticus of Alt Clut (Strathclyde), and Pabo Post Prydain was another (he may have been based at Papcastle). Rheged seems to have been one of these members of the Old North kingdoms that emerged during this period of intertribal warfare.[12] It has to be stressed, however, that the existence, historically, of something explicitly called the 'Kingdom of Rheged' remains in dispute by some.[13]

Rheged

Pabo was present at the Battle of Arfderydd (Arthuret) in 573, which may have been fought for control of the Solway.[14] Peredur and Gwrgi were also there, and these two were supposedly descendants of the Coeling family (Coel Hen) as well as being first cousins of Urien Rheged, (c. 550 – c. 590) so may have been associated with the Rheged area. The sources that mention the battle, however, (the Annales Cambriae and Aneirin's poem Y Gododdin) mention neither Rheged nor Urien, (casting doubt in the minds of some on the existence of both).[15] It may be that Urien took advantage of the confusion and weakness as a result of this savage battle to make his move to take over Rheged, or maybe he did this after the deaths of Peredur and Gwrgi some years later (the brothers were killed fighting the Angles in 580 or 584).

The extent of Rheged is disputed: none of the early sources tells us where Rheged was located.[16] Some historians believe that it was based on the old Carvetii tribal region - mostly covering the Solway plain and the Eden valley. Others say that it may have included large parts of Dumfriesshire, Lancashire and Yorkshire. The Kingdom's centre was based, possibly, at Llwyfenydd, believed to be in the valley of the Lyvennet Beck, a tributary of the River Eden in east Cumbria, or, alternatively, at Carlisle. However, one archaeologist points out that there is no archaeological evidence in Carlisle or elsewhere to suggest the location of a 'capital' of Rheged, and the interpretations of the literary sources are equally suspect.[17] Rheged could have been a name for a territory, or a people occupying an area, or both.[18] A consideration of the landscape aspects of the question by the same archaeologist, suggests that the Eden valley or the Rhinns / Machars area of Dumfries and Galloway offer the best places in which to locate a sub-Roman kingdom (but probably not both).[19]

The little that is known about Rheged and its kings comes from the poems of Taliesin, who was bard to Urien, King of Catraeth and of Rheged (and possibly overlord of Elmet). It is known, from the poetic sources, that under Urien's leadership the kings of the north fought against the encroaching Angles of Bernicia and that he was betrayed by one of his own allies, Morcant Bulc, who arranged his assassination after the battle of Ynys Metcaut (Lindisfarne) around 585 AD.

The lack of documentary or even archaeological evidence from this period of Cumbria's history has meant that history and legend have become intertwined and the fragments of certainty have become the basis of local myth. One of Cumbria's greatest heroes is Urien Rheged's son, Owain (usually Ewain in Cumbria), who is supposed to have lived at Castle Hewen, believed to be a Romano-British hillfort south of Carlisle. The poetic sources name him as the last king of Rheged (c. 590), having fought with his father against the Angles of Bernicia.

The Battle of Catraeth, fought by the Brythons (c. 600 AD) to try to recover Catraeth after Urien's death, was a disastrous defeat for them. Aethelfrith, the victor, probably received tribute from the kings of Rheged, Strathclyde and Gododdin (and maybe even from the Scots of Dalriada) thereafter.[20]

Christian saints

One aspect of the sub-Roman period in Cumbria, that is also uncertain as regards its historical evidence, is the early establishment of Christianity. A number of early 'Celtic' saints are associated with the region, including Saint Patrick, Saint Ninian and Saint Kentigern. Whether the dedications to these saints denote a continuance of a Celtic polity or populace through this period and the subsequent Anglian and Scandinavian periods, or whether they are the result of 12th-century revivals of interest in them, is unclear.

Patrick (died c. 460 or c. 493) was born to a family of local dignitaries at Banna venta Berniae, assumed to be Ravenglass (whose Roman name was Glannaventa) or somewhere in the Solway region of Carlisle, possibly near Birdoswald. However, other, non-Cumbrian locations have also been suggested for his birthplace. Several places are traditionally associated with Patrick, such as Aspatria and Patterdale, largely because both derive their names from other historical Patricks, but there is no evidence to suggest that there is any association with these places.

Saint Ninian, born about AD 360, may have been of Cumbrian origin, although, once again, there is no evidence to confirm this: his major connection seems to have been with Whithorn in Galloway. The name of Ninian has strong associations with Ninekirks near Penrith. Not only did Ninian give his name to the place, he is believed by some to have had a hermitage in the caves of Isis Parlis overlooking the present church, which was originally dedicated to him. Earthworks in the area also give tantalising clues to an early monastery here. The other place in Cumbria that has associations with this saint is Brampton Old Church with its Ninewells and St. Martin's Oak locations. Both of these 'Celtic' sites, it has been pointed out, stood on the Cumbrian side of the boundary line of the Anglian Hexham diocese.[21] Ninian is often credited with the conversion of the Cymry to Christianity, despite its original introduction to the area by Romans.

By the 6th century, however, it seems that the Cymry had fallen back into old pagan ways and that Saint Kentigern re-Christianised the area. Kentigern, or Mungo as he was affectionately known, was a contemporary of Urien Rheged (although one source claims that he was the illegitimate son of Owain mab Urien) who is known to have been a Christian, but his subjects might have been less devout. Around 553 Kentigern was expelled from Strathclyde, because of a strong anti-Christian movement. He fled as far as Wales, and could not find refuge in Cumbria, which was maybe also less devout. But the Christians won the battle of Ardderydd, between the Christian King Rhydderch Hael of Strathclyde and the pagan King Gwenddolau. After this Kentigern returned to Strathclyde. Once again, it has been noted, dedications to Kentigern are located in what may have been 'Celtic' areas of the region, as opposed to the Anglian Hexham diocese area (dedications to Saint Andrew being more popular here on the east side of the Eden/Irthing boundary) and the Norse 'Coupland' area (between the rivers Esk and Ehen).[22] As mentioned above, Rheged's involvement in this battle is not clear, but it seems they may have benefited by gaining the land of Caer-Wenddolau (modern Carwinley) by the Border Esk separating Cumbria from Dumfries and Galloway, and they may have even amalgamated with Strathclyde to form a dual kingdom.

Definite evidence of 6th-century Christianity in Cumbria is hard to find - no remains of stone-built churches exist and any wooden ones have disappeared. It is possible that the kingdom of Rheged's household supported a bishopric - perhaps based on Carlisle, and perhaps a monastery at Ninekirks existed by the end of the century, but both of these are disputable. There may have been an east–west oriented cemetery (indicative of Christian burials) at Eaglesfield, in the area controlled by Pabo, the name of which may reflect an eccles- (that is ecclesiastic) prefix.[23]

Life in 'Dark-age' Cumbria

Despite, or perhaps because of, the emergence of local chieftains and warbands, there are signs that the 5th and 6th centuries were not ones of economic strain in Cumbria (not more than usual, at least). De-forestation, usually an indication of increased farming production, seems to have occurred, according to the pollen records, at a steady level in post-Roman Cumbria (later than the rest of the country where de-forestation took place in Roman times). Where clearance had already occurred, it was sustained throughout these years. Flax, hemp and some cereal cultivation took place, and it appears that a "buoyant population" (in terms of numbers) enjoyed "a period of hospitable climate" up to the end of the 6th century.[24] At the end of the 6th century, however, the pollen records show quite a dramatic decline in human activity in some areas - factors accounting for this may include the after-effects of a visitation of the plague c. 547.

The collapse of Roman control had caused famine in the North; this led to "brigandage and the collapse of food production".[25] As a consequence, there was an increased pool of people who became slaves. Cumbria is likely to have become an international exporter of slaves, helping to pay for the exotic imports such as silks, wine, amber, gold and silver for the chiefs of the warbands (as noted in the poetic sources) - goods that were no longer being supplied via the Roman trading routes.[26]

The difficulties in finding archeologically certain 5th- and 6th-century rural settlements and finds, means that the most we can say about the rural economy is that it carried on more or less in the way it had done during Roman times. That is, some cereal production in the lowland areas, pasture being favoured over arable in the northern uplands, and a "strong bias in the rural economy in favour of cattle".[27]

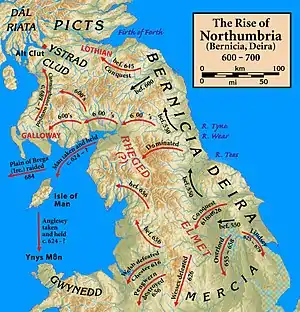

The Angles: Northumbrian takeover and rule, c. 600–875

The 7th century saw the rise to power of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria (just as the 8th saw the rise of Mercia, and the 9th that of Wessex). The Northumbrian kingdom was based on the expansionist power of Bernicia, which, by 604, had taken over their neighbouring kingdom of Deira, along with other kingdoms of the Old North such as Rheged, although the dating of the takeover, and the extent of the Anglo-Saxon settlement that followed, are a matter of contention amongst historians.[28] Documentary and archaeological evidence is lacking and qualified reliance is placed on place-names, sculpture and blood-group studies, all of which are open to challenge.

Takeover

The reign of Aethelfrith's rival, brother-in-law and successor, Edwin, saw Northumbrian power stretch as far as the 'Irish Sea Province' with the taking of the Isle of Man (c. 624) and Anglesey. How much involvement Rheged had in this move is unclear. The Northumbrian pursuit of power in this area and to the south of the Bernician/Deiran homeland, led to conflicts with the likes of Cadwallon (who defeated and killed Edwin in battle in 633), and later with Penda of Mercia, who defeated and killed (642) Oswald (who had previously defeated Cadwallon in 634). Northumbrian ambitions were eventually checked with the disastrous defeat of King Ecgfrith's forces in 685 at the hands of the Picts at the Battle of Dun Nechtain, but the north-west region, including the Cumbria area, remained firmly within the Northumbrian ambit during this period.

Anglian settlement

The extent of Anglian settlement of Cumbria during this period is unclear. It is likely that the spread of English occupation was concentrated around those areas of rich agricultural land and royal estates (used by the peripatetic royal household). Areas such as Strathclyde, Galloway and Cumbria and upland areas in general, may not have been affected as much as the lowland ones. Place-name evidence arguably shows a bilingual culture (Celtic and English) for a few decades at least, (probably amongst the administrative class), before the renaming of Celtic places by English ones took place.[29]

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1833421.jpg.webp)

The place-name evidence suggests that Old English (that is, Anglo-Saxon, or, in this case, Anglian) names are to be found in the lower-lying areas around the highland (modern Lake District) inner-core. These regions are the more fertile agriculturally, and many became parishes or townships in later times.[30] These places have the (perhaps early) elements such as -hām or -inghām ('village' or 'homestead'), examples being Addingham, Askham, Heversham, Brigham, Dearham. Most common is the form -tūn ('farmstead', 'village', 'settlement'), examples of which include Barton, Bampton, Broughton, Colton, Irton, Lorton and Embleton within the Lake District area[30] and Frizington, Harrington, Workington, Hayton, Clifton on the coast.

The ravages of bubonic plague, of which there were several visitations during the 7th century, are likely to have played some part in the process of Anglian expansion (rather than, say, the deliberate killing of Celtic peoples by the English, although some of that had taken place in Northumbria). Underproduction of children, because of plague, by the (mainly Celtic) 'disadvantaged' class, may have been offset by the overproduction of children of the (mainly English) 'advantaged' people.[31]

At least one historian[32] believes that the core, strategically important, area of the Solway and the lower Eden valley, remained essentially 'Celtic', with Carlisle retaining its old Roman 'civitas' status under Northumbrian overlordship, occasionally visited by the King of Northumbria and bishops such as Cuthbert, and overseen by a 'praepositus' (English: 'reeve'), a kind of permanent official. Also, " ...many inhabitants" continued to speak Cumbric "throughout the Bernician occupation." The exceptions, more colonised by the Northumbrian English than the rest of the Cumbrian region, were perhaps the following: a) the upper Eden valley, "perhaps colonised from Deira," in what was called by the Northumbrians Westmoringa land (that is, 'land west of the moors'), equating to the future shire of Westmorland, and including the area of the Lyvennet, reputedly containing Taliesin's hall of the men of Rheged, ("In the hall of the men of Rheged/ there is every/ esteem and welcome,"[33]) and the high-status residence at Bolton, plus the important church at Morland and including the Appleby and Ormside areas; b) the area to the east of the western edge of Bernicia (which may have reached the Eden river), along a strip about five miles wide west of the Pennine ridge, including the lost parish of Addingham, as well as such places as Skirwith and Kirkoswald (dedicated to King Oswald of Northumbria); c) the Cumbrian coast, probably settled from the sea; d) the south, which may have been subject to Wilfrid's attentions, and Cartmel which was given to Cuthbert.

(Some historians, however, do not see the praepositus official as evidence of permanent, Celtic, occupation).[34]

King Edwin, according to the Historia Brittonum, was converted to Christianity by Rhun, son of Urien, around 628. However, Bede states that Bishop Paulinus was the main force behind this. The conflict of sources echoes that of the two different varieties of Christianity competing with one another - the Celtic (Irish- and Scottish-based) and the Roman. An alternative view suggests that there were two baptismal sessions of Edwin, one done according to the Celtic Christian rite, and a later one done according to the Roman Christian ceremony. Rhun was probably present regularly at Edwin's court as a representative of Rheged. Later, the Bernician over-king, Oswiu (643-671), married twice - firstly Riemmelth of Rheged (granddaughter of Rhun), and secondly Eanflaed of Deira, thus uniting all three kingdoms. It is thus possible that a line of Anglian sub-kings ruled at Carlisle, from this time on, at least, on the strength of legal title and not just conquest.[35] Rhun's role in the baptism of Edwin and the marriage of Oswiu to Riemmelth, have been the subject of debate by historians concerning the veracity of Bede's account, the role of the Brythons in the conversion of the Bernicians, and the survival and independence of a kingdom called Rheged.[36] (At the Synod of Whitby in 664, the Celtic Church of the North was abandoned in favour of the Roman Church, which was dominant in the south of England. Maybe by then much if not all of Cumbria was ruled by the Northumbrian Kings. The area seems to have undergone a full-scale conversion to the Roman faith).

In 670, Oswiu's son—but not by Riemmelth—Ecgfrith ascended the throne of Northumbria and it was possibly in that year that the Bewcastle Cross was erected, bearing English runes, which shows that they were certainly present in the area. (It has been suggested that the Bewcastle monument and that of Ruthwell, with which it is often paired, may have been markers of religious communities at the eastern and western limits of the diocese of Lindisfarne in this region, with Bewcastle marking the western edge of Bernicia and the diocese of Hexham,[37] and even that they may indicate the Northumbrian adoption of the eastern and western boundaries of the old kingdom of Rheged).[38] But it seems that Cumbria was little more than a province at this time and, although Anglian influences were clearly seeping in, the region remained essentially Brythonic and retained its own client-kings. In 685, when Saint Cuthbert was granted lands in Cumbria by Aldfrith, the new King of Northumbria, it is said he was given Cartmel and all the Britons therein, showing that the Brythons were still predominant, in the rather remote (from Northumbria) Furness district, at least. Cuthbert visited 'Lugubalia' (Carlisle) in the same year, and was shown the Roman city wall and a fountain or well, by the praepositus mentioned above. Some have thought that this is an indication of city life persisting through the 5th and 6th centuries and into the 7th. However, other evidence suggestive of increased agriculture and a smaller population may indicate otherwise.[34]

Church and state

Legend has it that Cuthbert foresaw the death of Ecgfrith (at Dun Nechtain), while visiting the church at Carlisle, warning Ecgfrith's (second) wife Eormenburg whom he was accompanying. Bede reckoned that the decline of Northumbrian power dated from this year (685), but military set-backs were only part of the picture. Inter-family struggles amongst the various branches of the royal family played a part, as did the granting of royal estates (the so-called villae) to the Northumbrian Roman church (in return for support for the various attempts on the throne), encouraged by the aristocracy who wished to lessen the burden of royal power and taxation.[39] Cuthbert's grant of lands around Cartmel was one example of this process of degradation of royal resources and power.

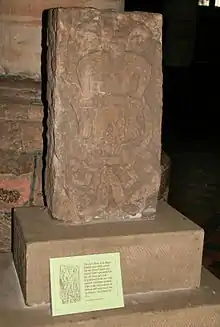

The huge estates given to the Church meant that it became an alternative power-base to the king. This was the great age of the Northumbrian Church 'renaissance', driven by dynamic church leaders such as Cuthbert (who inspired local disciples such as Herbert of Derwentwater), Benedict Biscop and Wilfrid: the age of the building of monasteries and churches (the larger ones in stone); of the production of the Lindisfarne Gospels and other manuscripts; of elaborately decorative church art, some situated in Cumbria, such as the Bewcastle Cross shaft, the Ireby Cross, and the golden liturgical water bowl found at Ormside. In Cumbria, there were monasteries at Carlisle, Dacre, and Heversham, known from literary sources; and at Knells, Workington and Beckermet, known from stone inscriptions; and possible sites at Irton, with its early 9th-century cross, Urswick and Addingham without any evidence attached to them.[40] Anglian sculpture was invariably to be found at monastic sites (which, in turn, were to be found in good agricultural areas). The crosses themselves were not grave markers (a few cemeteries had grave slabs), but were "memorials to the saints and to the dead."[41][42]

The use of stone for the buildings, crosses and inscriptions was symbolic - it recalled the authority of Rome and its classical sculptures, and it recalled the words of Christ to Saint Peter ("You are Peter, the Rock, on this rock I will build my church"). The new Church of Rome was now to be seen as the successor of the old Roman Empire.[43] Communication by sea seems to have been an important factor in the siting of these church centres, which would have drawn civilian habitation to them, in the way that the 'vici' were drawn to the Roman forts. The suffix -wic, as in Urswick and Warwick (east of Carlisle), indicates the presence of a market.[44]

The rise of the church, and the parallel decline in fortune of the secular royal power, meant that Northumbria and its Cumbrian appendage were not strong enough militarily to fend off the next set of raiders and settlers (who first attacked the Lindisfarne monastery in 793) - the Vikings. By 875, the Northumbrian kingdom had been taken over by Danish Vikings. Cumbria was to go through a period of Irish-Scandinavian (Norse) settlement with the addition, from the late 9th century on, of the influx of more Brittonic Celts.

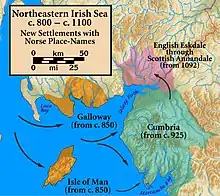

Vikings, Strathclyde Brythons, Scots, English and 'Cumbria', 875–1066

Vikings were of three types of Scandinavians: Swedes, whose expeditions were mainly eastwards to places such as Russia; Norwegians (Norse), who concentrated on the western seaboard of what is now Scotland, on Ireland, on the Irish Sea coasts including the Dublin area, on the Isle of Man, and on what is now Cumbria; and thirdly, Danes, who were more interested in eastern England and the north-east (including the Northumbrian kingdom), and what is now Yorkshire. The activities of the Vikings included a mix of trading, raiding, settlement and conquest.

The result of these attacks was the collapse of the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria. The Danes made serious assaults on the east of England, culminating in the 'Great Army' attack of 865, bent on conquest, rather than just raiding for booty. As a result, the Deira region of Northumbria became part of the Danelaw, ruled from York. Halfdan Ragnarsson attempted to conquer Bernicia in 875, and may have sacked Carlisle on the way to battling the Picts (although the source is unreliable). The monks fled with Saint Cuthbert's body to the west and many church dedications to him in Cumbria must date from this time.[45] However, the eventual outcome, in the 880s, was an accommodation with the church community of Cuthbert who were granted lands between the Tees and Forth under Danish overlordship (with a semi-independent lordship based at Bamburgh).

The Norse made devastating raids on the Northumbrian monasteries in the early 800s, and, by 850 had settled in the Western Isles of Scotland, in the Isle of Man, and in the east of Ireland around Dublin. They may have raided or settled in the west coast of Cumbria, although there is no literary or other evidence for this.

The collapse of Anglian authority affected what happened in Cumbria: the power vacuum was filled by the Norse, the Danes in the east, and by the Strathclyde Brythons who themselves came under pressure from the Norse in the 870s and 890s. (The expansion of the Scots to the north and the English to the south also complicates the picture). Once again, our sources for what happened are extremely limited: the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, for example, barely mentions the north. We are thrown back upon the study of place-names, artifacts, and stone sculptures, to fill in the picture of 10th-century Cumbria. As a result, there is some dispute amongst historians concerning the timing and the extent of the influx of Vikings and Strathclyders into Cumbria.

Scandinavian settlement

Place-name[46][47][48] and sculptured stone[42][49][50] evidence suggests to one historian that the main Scandinavian colonization took place on the west coastal plain and in north Westmorland, where some of the better farming land was occupied. The warriors who settled here encouraged stone sculptures to be made. However, the local Anglian peasantry seems to have survived in these areas as well. Some, less successful, occupation of other lowland areas took place, along with, thirdly, occupation of 'waste' land in the lowland and upland areas. This occupation in the less-good farming areas led to place-names in -ǣrgi, -thveit,, -bekkr and -fell, although many of these may have been introduced into the local dialect a long time after the Viking age.[51] "Southern Cumbria", including the future Furness region (Lonsdale Hundred) as well as Amounderness in Lancashire, was also "entensively colonized".[52]

The occupation was likely to have been largely by the Norse between about 900 and 950, but it is unclear whether they were from Ireland, the Western Isles, the Isle of Man, Galloway, or even Norway itself. Just how peaceful, or otherwise, the Scandinavian settlement was remains an open question. It has been suggested that, between c. 850 and 940, the Scots on the one hand, and the Norse of the Hebrides and Dublin on the other, were in collusion as regards what seems to have been peaceful Gaelic-Norse settlement in west Cumbria.[53] It has also been suggested that the Hiberno-Norse in Dublin were prompted to colonise the Cumbrian coast after being temporarily expelled from the city in 902. The successful attempt by Ragnall ua Ímair to conquer the Danes in York (around 920) must have led to the Dublin - York route through Cumbria being frequently used. In Westmorland, it is likely that much colonization came from Danish Yorkshire, as evidenced by place-names ending in -by in the upper-Eden valley region (around Appleby),[54] especially after the eclipse of Danish power in York in 954 (the year of the death of the Norse King of York, Erik Bloodaxe, on Stainmore).

There was no integrated and organized 'Viking' community in Cumbria - it seems to have been more a case of small groups taking over unoccupied land.[55] (However, others argue that the place-name evidence points to the Scandinavians not just accepting the second-best land, but taking over Anglian vills as well.[56]) It may be that Scandinavian warriors took over from Anglian ones in the major estates, perhaps the so-called 'multiple estates', (perhaps renaming them into a Scandinavian form), caused Scandinavian-influenced stone sculptures to be set up, and maybe allowed peasant Scandinavian peasant-farmers to 'in-fill' on land around the estates, such in-filling often denoted by Scandinavian names.

In Copeland, (Norse kaupa-land, 'bought land'), land purchased by the Norse on the south-west coast, for example, tenure patterns seem to show cornage and seawake tenures held on the lowland coast, other freehold townships on rising land towards the foothills of the Lake District, and, thirdly, other settlements, held directly in the less-favourable valley areas (in the 'free chase' or forested regions that were part of the multiple estate set-up). This suggests Scandinavian takeover in successive generations. Firstly, of the multiple estates, with township-names ending in -by, and then later settlement of new farms further inland, during the 10th to 12th centuries, in places denoting clearance (-thveit, '-thwaite') or old shieling grounds (-ǣrgi).[57]

The evidence of the sculpture is unclear when it comes to influences. Although called by some 'pagan' or 'Viking', it may be that some, if not most, of the crosses and hogback sculpture (to be found almost wholly in south Cumbria, away from the Strathclyde area), such as the Gosforth Cross and the Penrith 'Giant's Grave', reflect secular or early Christian concerns, rather than pagan ones.[58] Due to the lack of documentary corroboration or of inscriptions on the sculptures themselves, we are thrown back on comparative analyses of the ornamentation and other stylistic indicators.[59] The result is that we are uncertain not only about when the crosses and hogbacks were made, but also about who caused them to be made. The decline of the monasteries in the later Anglian period probably led to the new Scandinavian, secular lords ordering the stones to be made, but many reflect Anglian (Northumbrian) styles and motifs, and have an amalgamation of Christian concerns (for example, Crucifixion scenes) and Viking iconography and myths (for example, scenes depicting Ragnarök and Wayland the Smith). The classic example of this mingling of pagan and Christian story-telling is the Gosforth Cross.[60] In another example, does the sculpture to be found at Kirkby Stephen's church depict a bound Loki or a bound Satan? It is appropriate, therefore, given these ambiguities in the evidence, to talk, not about 'Viking sculpture', but about 'Viking-age sculpture'.[61]

Cumbria is notable for having the largest number of hogbacks and for their tallness and narrowness compared to other northern stones;[62] for having a special type of circle-head to the crosses;[63] for having the most 'hammer-head'- shaped crosses;[64] for using a 'running Stafford knot' design and a type of spiral-scroll work;[65] for having a local 'Beckermet school' of stones perhaps influenced by, or influencing, cross designs to be found on the Isle of Man;[66] and for its links with the stone sculpture to be found in south-west Galloway (Galloway being a Northumbrian province during this period).[67]

The influence of the Vikings remained strong until the Middle Ages, particularly in the central region. A Norse-English creole was spoken until at least the 12th century and evidence of the introduction of the Viking political system is shown by several possible Thing mounds throughout the county, the most significant of which is at Fellfoot in Langdale.

As an example of Viking relics, a hoard of Viking coins and silver objects was discovered in the Eden valley at Penrith.[68] Also in the Eden valley were finds at Hesket and at Ormside, which has been mentioned above as the site of a possible Viking grave-good. The other areas of Viking finds include Carlisle (west of the Cathedral), pagan graves at Cumwhitton[69] and finds in the Lune valley and on the west coast (for example, Beckermet, where a hoard was discovered in 2014, Aspatria and St. Michael's Church, Workington). However, relatively little else has come down to us apart from the sculpture. Despite this, interest in the Viking aspect of Cumbria, arguably almost on a par with that of the Neolithic, Roman and Border Reivers aspects, has been fuelled, particularly from the 19th century on, by the tourism boom in the Lake District (with its preponderance of Scandinavian names), by notions of rugged, free and independent 'statesmen' (estates men) of Viking stock, forming, according to William Wordsworth, a "Perfect Republic of Shepherds and Agriculturalists",[70] and by an interest in Scandinavian history and language promoted by writers and antiquaries such as W. G. Collingwood, Thomas de Quincey, William Slater Calverley, Hardwicke Rawnsley, Richard Saul Ferguson, Charles Arundel Parker, George Stephens, Thomas Ellwood, and others, dubbed the "Old Northernists" by some modern historians.[71]

Strathclyde Brythonic settlement

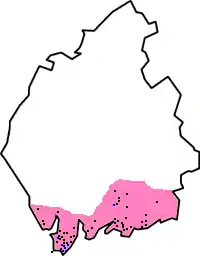

Some historians argue that the vacuum left by the Northumbrian eclipse in Cumbria led to people from the Kingdom of Strathclyde (also confusingly known at this time as 'Cumbria', the 'land of our fellow countrymen' or 'Cymry') moving into the north of what we now call the English county of Cumbria.[72] Others make the case for a survival of Cumbric place-names pre-dating the Anglian takeover and see no reason to posit a tenth-century expansion of Cumbric-speaking Strathclyders.[73][74]

(Historians disagree whether Cumbria and Strathclyde were different names for the same kingdom. Fiona Edmonds and Tim Clarkson argue that up to the late ninth century the Brittonic kingdom north of the Solway was named Alt Clud after its stronghold on Dumbarton Rock, but after the Vikings conquered the rock in 870 the name no longer made sense and it was renamed Strathclyde. In the tenth century the kingdom recovered and expanded south of the Solway, and then the name Strathclyde, the valley of the Clyde, was too restrictive and the kingdom came to be known as Cumbria).[75][76]

The place-name evidence,[77][78][79] appears to confirm a 10th-century takeover of north Cumbrian estates by the Strathclyde kings. This, along with evidence of dedication sites to Saint Kentigern, suggests that such a movement was confined largely to the Solway Plain, as well as the Irthing and the lower Eden valleys (southwards to the line of the River Eamont). The bulk of what was to become Cumbria, south of the Eamont, seems to have been untouched by this movement of Brittonic peoples, although a case has been made that all of what became Cumberland, plus Low Furness and part of Cartmel, were under Strathclyde control, whether directly or indirectly.[80]

It is thought possible that this settlement of fellow Christians was encouraged by the Anglo-Celtic aristocracy, probably with the support of the English south of the Cumbrian region, as a counterweight against the Hiberno-Norse. It may be that, up to around 927, an alliance of Scots, Brythons, Bernicians and Mercians fought against the Norse, who were themselves allied to their fellow Vikings based in York. [81]

The situation altered with the coming of Athelstan to power in England in 927. Athelstan defeated the Vikings of York in 927 and moved north. On 12 July 927, Eamont Bridge (and/or possibly the monastery at Dacre, Cumbria, and/or the site of the old Roman fort at Brougham) was the scene of a gathering of kings from throughout Britain as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the histories of William of Malmesbury and John of Worcester.[82] Present were: Athelstan; Constantín mac Áeda (Constantine II), King of Scots; Owain of Strathclyde, King of the Cumbrians; Hywel Dda, King of Wales; and Ealdred son of Eadulf, Lord of Bamburgh. Athelstan took the submission of these other kings, presumably to form some sort of coalition against the Vikings. The growing power of the Scots and perhaps also of the Strathclyders, may have persuaded Athelstan to move north and attempt to define the boundaries of the various kingdoms.[83] This is generally seen as the date of the foundation of the Kingdom of England, the northern boundary of which was the Eamont river (with Westmorland being outside the control of Strathclyde).

However, given the increasing threat from English power, it seems that Strathclyde/Cumbria switched sides and joined with the Dublin Norse to fight the English king who was now in control of Danish Northumbria and presenting a threat to the flank of Cumbrian territory. After the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, (an English victory over the combined Scots, Strathclyders and Hiberno-Norse), Athelstan came to an accommodation with the Scots. During this time, Scandinavian settlement may have been encouraged by the Strathclyde overlords in those areas of Cumbria not already taken by the Anglo-Celtic aristocracy and people.[84]

In 945 Athelstan's successor, Edmund I, invaded Cumbria. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the defeat of the Cumbrians and the harrying of Cumbria (referring not just to the English county of Cumberland but also all the Cumbrian lands up to Glasgow). Edmund's victory was against the last Cumbrian king, known as Dunmail (possibly Dyfnwal III of Strathclyde), and, following the defeat, the area was ceded to Malcolm I, King of Scots, although it is probable that the southernmost areas around Furness, Cartmel and Kendal remained under English control.

The Scots and 'Cumbria'

One historian has suggested that the notion of 'Strathclyde/Cumbria' presents too much of a picture of Strathclyde dominating the relationship, and that maybe the Cumbrian area – including the Solway basin and perhaps lands in Galloway, but also specifically the area that became Cumberland county later (the so-called 'Cumbra-land') – was where the prosperity and action lay. It is even suggested that there were two kingships, one of the Clyde area (effectively 'annexed' by Donald II of Scotland in the late 9th century) and another of the Cumbrian (as defined above), the latter having, through marriage or by patronage, increasingly Scottish input.[85] Much of this interpretation rests on the writings of John Fordun and has been challenged by other historians.[86]

Whatever the background, from c. 941, it has been suggested, Cumbrian/Scottish rule may have lasted around 115 years, with territory extending to Dunmail Raise (or 'cairn') in the south of the Cumbrian region (and perhaps Dunmail was trying to extend it through 'Westmoringa land', the future Westmorland, when he incurred the wrath of Edmund I, who regarded the area as English, in 945 ).[87] Edmund, having ravaged Strathclyde/Cumbria, ceded it to the King of Scots, Malcolm I of Scotland, either to define the limits of English rule in the North-West, and/or to secure a treaty with the Scots to prevent them joining up with the Norse and Danes of Dublin and York.[88]

In 971, Kenneth II of Scotland raided 'Westmoringa land', presumably trying to extend the Cumbrian frontier to Stainmore and the Rere Cross. In 973, Kenneth and Máel Coluim I of Strathclyde obtained recognition of this enlarged Cumbria from the English king Edgar. 'Westmoringa land' thus became a buffer zone between the Cumbrian/Scots and the English.

Church dedications to the Scottish patron saint, Saint Andrew, are to be found around the edges of what was 'Cumbra land': at Penrith, (controlling the Eamont crossing), Dacre, and Greystoke (controlling major roadways to the west of Penrith running north–south and east–west).[89] However, it is possible that these dedications are Anglian (Northumbrian) in origin, introduced by the monks of Dacre following the lead of Wilfrid, who adopted Saint Andrew as his patron saint.[90]

The English and Cumbria

In 1000, the English king, Ethelred the Unready, taking advantage of a temporary absence of the Danes in southern England, invaded Strathclyde/Cumbria for reasons unknown - perhaps the Strathclyders/Cumbrians were allying themselves with the Scandinavians or the Scots against English interests.[91] After the takeover of the English throne by Cnut in 1015/16, the northern region became more disturbed than ever, with the fall of the Bamburgh earls and the defeat of the Northumbrian earl by the Scots and Strathclyders/Cumbrians at the Battle of Carham in 1018.[92]

Attempts by the Scots and Cnut to control the area ended with Siward, Earl of Northumbria emerging as a strongman. He was a Dane, becoming Cnut's right-hand man in the north by 1033 (Earl of Yorkshire, around 1033; and also Earl of Northumbria, around 1042). Sometime between 1042 and 1055, Siward seems to have taken control of Cumbria south of the Solway, perhaps responding to pressure from the independent lords of Galloway or from Strathclyde[93] or perhaps taking advantage of Scottish troubles to do with the reign of Macbeth, King of Scotland. The routes through the Tyne Gap and also via the Eden Valley over Stainmore threatened to allow the Scots overlords of Strathclyde/Cumbria to raid Northumbria and Yorkshire respectively (although most Scots' raids took place by crossing the River Tweed into Lothian in the east).

Some evidence comes from a document known to historians as "Gospatric's Writ", one of the earliest documents to do with Cumbrian history. This is a written instruction, issued either by the future Gospatric, Earl of Northumbria[95] or Gospatric, son of Earl Uhtred, that was addressed to all Gospatric's kindred and to the notables dwelling in the "all the lands that were Cumbrian" (on eallun þam landann þeo Cōmbres); it ordered that one Thorfinn mac Thore be free in all things (þ Thorfynn mac Thore beo swa freo in eallan ðynges) in Allerdale, and that no man is to break the peace which was given by Gospatric and Earl Siward. Some historians believe that such phraseology indicated that Siward took over the region from its previous rulers, perhaps as the price for supporting Malcolm against MacBeth.[96][97] The writ can be interpreted as showing that power was maintained locally in the hands of local magnates, with Siward being given fairly scant deference, rather than an acknowledgement of effective suzerainty.[92]

Siward aided his kinsman Malcolm III of Scotland, possibly known as 'the King of the Cumbrians' (but possibly confused with Owen the Bald of Strathclyde) at the Battle of Dunsinane in 1054, against Macbeth who, although escaping, was eventually killed in 1057. Despite this receipt of help, Malcolm invaded Northumbria in 1061, possibly trying to enforce his claim as 'King of the Cumbrians', (that is, to regain the lost territory of Cumbria south of the Solway taken by Siward), whilst Siward's successor as earl, Tostig Godwinson, was away on pilgrimage. It is likely that Malcolm succeeded in regaining the Cumberland part of Cumbria in 1061: in 1070 he used Cumberland as his base to attack Yorkshire.[98] This 1061 incursion was the first of five such raids by Malcolm, a policy that alienated the English Northumbrians and made it harder to fight the Normans after the invasion of 1066. For the next thirty years, Cumbria, probably down to the Rere Cross boundary, was in the hands of the Scots.[99]

Malcolm III, King of Scots, held the Cumberland territory, (probably down to the River Derwent, River Eamont and Rere Cross on Stainmore line), until 1092, one year before his death in battle. The fact that he did this without challenge was partly the result, as far as the pre-Norman conquest era is concerned, of turmoil and alienation amongst the Northumbrian and Yorkshire nobles, (drawn from the ranks of the old Anglo-Saxon Bamburgh royal family and Danish/Norse nobles respectively), as well as the disaffection of the St. Cuthbert monks (in Durham), due to the rule of the West Saxon outsider Earl Tostig.[100] Other factors include the absentee nature of Tostig's rule in the North, and his friendship with King Malcolm.

High medieval Cumbria, 1066–1272

Norman Cumbria: William I, William 'Rufus', Henry I, and David I, 1066–1153

The Norman takeover of the Cumbria region took place in two phases: the southern district, covering what were to become the baronies of Millom, Furness, Kendale and Lonsdale, were taken over in 1066 (see below under "Domesday"); the northern sector (the "land of Carlisle") was taken over in 1092 by William Rufus.

William the Conqueror

The Norman conquest of England proceeded only slowly in the North of the country, perhaps due to the relative poverty of the land (for example, not suitable for growing the Normans' preferred wheat, as opposed to oats),[101] and to various uprisings in England as well as in Normandy that meant that William I had to be elsewhere.

William attempted to rule the north firstly by appointing local nobility such as Copsi (earl of Northumbria and unpopular because of his former alliance with the hated Tostig and his heavy taxation levies); and then Cospatrick who joined forces with the remnants of the Anglo-Saxon claimants to the throne (such as Edgar the Ætheling, who were probably given sanctuary, when necessary, in Cumberland by Malcolm III who married Edgar's sister, Saint Margaret of Scotland, around 1070). These claimants, plus the Danes, were a constant threat against William. The Harrying of the North was the result, with the northern lands being controversially ravaged by William, followed by what Kapelle calls "government by punitive expedition" and the use of Norman place-men.[102] It is unclear whether the Harrying affected Scottish-held Cumbria: most of the damage was done in Yorkshire, Durham and Northumbria.

The various raids by Malcolm, the Danes and the English rebels, plus regular uprisings by Northumbrian nobles, all contributed to the weakness of William's control of the North. Most of Cumbria, therefore, remained in the hands of the Scots, as well as being a base for brigands and dispossessed rebels. Cumbria south of the mountains, the future Westmorland south of the Eamont, and North Lancashire, had been held by Tostig in 1065, during which time he had battled against both the Scots and bands of brigands.[103] It is likely that this situation persisted for much of William's reign as well.

William finally brought Northumbria under control: his son, Robert Curthose, building the castle at Newcastle upon Tyne in 1080. Robert de Mowbray's appointment as Earl of Northumbria in 1086, and the building of "castleries" (territories administered by a constable from a castle) in Yorkshire, helped to clear up the brigandage problem.

Domesday

When the Normans conquered England in 1066, much of Cumbria was a no-man's-land between England and Scotland which meant that the land was not of great value. Secondly, when the Domesday Book was compiled (1086), Cumbria had not been conquered by the Normans. Only the southern part of the county, (the Millom, Furness, and part, or all, of Cartmel peninsulas), known as the Manor of Hougun, that which included lands held by Earl Tostig, was included, and even that was only as annexes to the Yorkshire entry. (There is some doubt as to whether Hougun was indeed an administrative district, or merely the chief vill in Furness and Copeland under which the other vills were listed).[104]

For the most part, the Cumbrian Domesday entries are little more than a list of place names and the amount of taxable land therein, with the names of the pre- and post-conquest landowners - a much sparser account than much of the rest of England. This in itself shows the isolated and remote nature of the area at this time, but the entries also provide evidence that Cumbria's prosperity had decreased significantly since the middle of the previous millennium - perhaps in part caused by the Conqueror's Harrying of the North. In addition, it has been suggested that the Domesday entry offers a snapshot of the "transition between the Anglo-Norse and Norman worlds in the 11th century", and suggests a largely self-governing area with a lack of the shire and wapentake structure that prevailed further south in England.[105]

William II

William II of England (William "Rufus") recognised that the state of affairs, as left to him by William I in 1087, was only a holding solution to the problems of the unsatisfactory position of the Normans above the Humber in the East and above the Ribble to the West. Rufus granted Ivo Taillebois estates in southern Westmorland and southern Cumberland - later to become the baronies of Kendal, Burton in Lonsdale and Copeland. It is possible that these lands, the extent of which are open to dispute, were granted to Ivo later, in 1092, at the same time as Roger the Poitevin was granted Furness and Cartmel, thus defining the extent of the future county of Westmorland and the division of Lancashire north and south of the sands.[106] This, together with the complementary strengthening of Norman control east of the Pennines, may have provoked Malcolm III's 1091 invasion of Northumbria.[107]

The unsatisfactory end, as far as Rufus was concerned, to the invasion of Scotland that followed Malcolm's raid, led him to try another approach: in 1092, he took over Cumberland by expelling the local lord, Dolfin, (who may or may not have been related to Earl Cospatrick).[108][109] Then, he built the castle at Carlisle and garrisoned it with his own men, and sent peasants, possibly from Ivo Taillebois' Lincolnshire lands, to cultivate the land there.[110] The takeover of the Carlisle area was probably to do with gaining territory and providing a strongpoint to defend his north-west frontier.[111] Kapelle suggests that the takeover of Cumberland and the building at Carlisle may have been designed to humiliate King Malcolm or to provoke him into battle.[112] The result was the last invasion by Malcolm and his own, plus his son's, death at the Battle of Alnwick (1093). The subsequent contest for the succession to the Scottish throne (between Donald II of Scotland and Edgar, King of Scotland) allowed Rufus to maintain his hold on the Cumberland and Carlisle areas until his death in 1100.

Henry I

A step-change occurred in the governance of the Cumbria area with the succession of Henry I of England. Henry enjoyed good relations with both Alexander I of Scotland and Henry's nephew, David I of Scotland, and therefore he could concentrate on developing his northern lands without the threat of a Scottish invasion.[113] Either he or his predecessor, Rufus, possibly around 1098, granted Appleby and Carlisle to Ranulf le Meschin who became the strongman of the north-west frontier.[114] (Others place the date of the grants after the Battle of Tinchebrai, that is, 1106 onwards).[115] Ranulf was the third husband of Lucy of Bolingbroke, the first husband of whom had been Ivo Taillebois, whose Cumbrian and Lincolnshire lands he inherited.

Although he was sometimes called an earl of Cumberland, it seems that he was rather a "power" (the foundation deed of Wetheral Priory, which Ranulf set-up, calling him a "potestas"). He was mentioned in a 1212 source as "Earl Ranulf, sometime lord of Cumberland", the earldom referred to being that of Chester. There was probably a distinction in the minds of contemporaries between the king's borough of Carlisle (inhabited largely by the Norman French and/or English) and Cumberland, (consisting of Brythons, Irish, Norse and English folk).[116] Ranulf created baronies for his brother-in-law, Robert de Trevers (based at the castle at Burgh-by-Sands), and for Turgis Brandos (based at Liddel), indicating "a high level of delegated authority"[117] It may be that no Royal acts were promulgated in Cumberland and Westmorland during Ranulf's time, and that the King's writ did not run here, again pointing to the semi-regal position of Ranulf and Henry's desire not to interfere. Ranulf became Earl of Chester in 1121, giving up his Cumbrian "honour" (group of estates), possibly as part of the purchase price for the Chester title and lands. This may suggest that his rule in Cumbria was more of an office-holding position than a feudal holding of lands, as otherwise he would have kept his Cumbrian lands intact for life.[118]

Henry I himself visited Carlisle the following year, from October or November 1122. While there, he ordered the castle to be fortified and created "several tenures that would come to be regarded as baronies" : William Meschin in Copeland (where William built Egremont Castle); Waltheof, son of Gospatrick in Allerdale; Forn, son of Sigulf, in Greystoke; Odard, the sheriff, in Wigton; Richard de Boivill in Kirklinton.[119] There is some doubt as to whether these enfeoffments were new or whether they were confirmations of tenants-in-chief under Ranulf's previous administration. Sharpe argues that Henry did not create "the institutions of county government" when he took charge directly.[120]

Henry also took direct control (perhaps in the years after 1122) in Carlisle partly in order to ensure that the running of the silver mine at Alston was done from there. He also confirmed the property and rights of the monks of Wetheral; and he established the Augustinian priory of Saint Mary at Carlisle, becoming, in 1133, Carlisle Cathedral when a new diocese was created. The creation of the new diocese, covering the areas of Carlisle, the Eden valley, Allerdale and the Appleby region of Westmorland only, was largely to avoid having the Bishop of Glasgow in charge of ecclesiastical affairs as he had been prior to this point. There was no comparable creation of a county sheriff, as happened in other shires of England: however, a sheriff of Carlisle seems to have been created, perhaps some time between 1130 and 1133, to run the King's business.[121]

Henry, besides promoting his Norman allies into positions of power in the north, was also careful to install some local lords into secondary roles. For example, two Anglo-Saxon northerners, probably from Yorkshire, were Æthelwold, who became the first Bishop of Carlisle, and Forn of Greystoke. Waltheof of Allerdale was a Northumbrian.[122]

Sharpe, therefore, sees the years of Henry I as being transitional ones: from Carlisle and Appleby under the control of the strongman Ranulf Meschin, to the partial introduction of a shire system by 1133. Phythian-Adams, meanwhile, sees Norman control as being innovative, rather than just using existing institutions and tenures. Kapelle emphasises the colonization of the North by Henry using "new men": western Normans and Bretons, counterweights against the two Williams's use of the upper Normandy establishment.[123][124][125]

David I of Scots

With the death of Henry I in 1135, England fell into a civil war, known as The Anarchy. Stephen of Blois contested the English crown with Henry's daughter, Matilda (or Maude). David I of Scotland, who was Prince of the Cumbrians (1113–1124), and Earl of Northampton and Huntingdon, had been King of Scots since 1124. Having been brought up in the court of his mentor and uncle, Henry I, as very much a Norman prince, he supported the claims of Matilda over those of her cousin, Stephen of Blois.

Professor Barrow asserts that, even at the beginning of his reign, David was thinking of the lands of Carlisle and Cumberland, believing, as he did, that "Cumbria" (that is, the previous entity of Strathclyde/Cumbria, covered by the diocese of Glasgow) was under the overlordship of the King of Scots, and stretched as far as Westmorland and possibly down to north Lancashire or even to the River Ribble.[126] When he took possession of Carlisle in 1136 (taking advantage of the turmoil in English affairs at the time), therefore, it was not entirely an opportunistic act, and the land was not held by David as a vassal of Stephen, as has been suggested by some.[127] The (first) Treaty of Durham (1136) ceded Carlisle and Cumberland to David.

David and his son, Earl Henry, seem to have ruled jointly. They gave north Westmorland (around Appleby), in the late 1130s, to Hugh de Morville. David's nephew, William became lord of Allerdale, Skipton and Craven. The previous lordship grants that David had made north of the border (as it had been under Henry I) were maintained (that is: Annandale under Robert de Brus, 1st Lord of Annandale, Eskdale, Ewesdale and Liddesdale). Likewise, the lordships south of what had been the border were also kept (that is: Liddel, Kirklinton, Scaleby, Wigton and Burgh-by-Sands). The diocese of Carlisle was also accepted.[128]

During David's control of Carlisle and Cumberland (areas such as Gilsland, Kentdale, Copeland, Furness and parts of Westmorland still had "separate identities"), Carlisle became a "chief place of Scottish government", but not the chief place as some have suggested.[129]

David may have been intending to enlarge his control of northern England when he fought at the Battle of the Standard, some of the soldiers of David's force being Cumbrians (from south of the Solway-Esk line, that is). Despite losing the battle, David kept his Cumbrian lands, and his son Henry was made Earl of Northumberland at the (second) Treaty of Durham (1139). This arrangement lasted another twenty years, during which David minted his own coins using the silver from the Alston mines, founded the abbey at Holm Cultram, kept the north largely out of the civil war of Stephen and Matilda, and, by the "Carlisle settlement" of 1149, obtained a promise from Henry of Anjou that, upon the latter's becoming King of England, he would not challenge the King of Scots's rule over Carlisle and Cumberland. David died at Carlisle in 1153, a year after his son Henry.

Henry II, 1154–89

The pattern of trading upon the weakness of one side or the other continued as regards Anglo-Scottish relations in 1154 when Henry of Anjou became King of England. (The Angevins were also known, from 1204 on, as the Plantagenets). King David of Scotland's death left an eleven-year-old boy, Malcolm IV, on the Scottish throne. Malcolm had inherited the earldoms of Cumbria (and Northumbria) as fiefs of the English crown, and did homage to Henry for them. However, at Chester, in July 1157, Henry demanded, and obtained, the return of control to England of Cumbria and Northumberland. The King of Scots was given the honours of Huntingdon and Tynedale in return, and relations between the two countries were amicable enough, although Henry and Malcolm seem to have fallen out at another meeting in Carlisle in June 1158, according to Roger of Hoveden.[130]

During his 1158 visit to Carlisle, Henry may have issued a charter to the leading men of the city, and he may have visited again in 1163, drawn to the area not only for political reasons but also because of his love of hunting in the Inglewood Forest.[131]

Henry took the opportunity of this relative peace to increase royal control in the north: justices toured the remote northern areas, taxes were collected and order was maintained. Hubert I de Vaux was given the Barony of Gilsland in order to strengthen defences.[132] The accession to the Scottish throne of William the Lion in 1165 brought border wars, (the war of 1173–74 saw Carlisle besieged twice by the Scottish king's forces, with the city being surrendered by the constable of Carlisle Castle, Robert de Vaux, when food ran out), but no giving up of Cumbria (or Northumberland) to the Scots, despite Henry's troubles after the murder of Thomas Becket and the Scots' alliance with France. The Treaty of Falaise of 1174 formalised a rather coercive peace between the two countries.[133]

Indeed, it was around this time that the ancient counties which made up modern Cumbria came into existence. Westmorland, in 1177, was formally created from the baronies of Appleby and Kendal. The barony of Copeland was added to the Carlisle area to form the county of Cumberland in 1177. Lancashire was one of the last counties to be formed in England in 1182, although its boundaries may have been fixed around 1100. Why the Furness and Cartmel peninsulas were included in the county of Lancashire when they are entirely cut off from the main body by Morecambe Bay is not immediately obvious. If the borders were settled as early as 1100 the decision may have been due to the influence of Roger de Poitou who held lands on both sides of the Bay, but it is more likely that it was a result of the cross-sands communications between Furness and Lancaster being stronger than those with Cumberland and Westmorland to the north due to the difficulties of travelling out of the area.

Henry made a final visit to Carlisle in 1186, in order to settle ongoing trouble in Galloway, a visit that throws some light on the leading personalities in Carlisle at the time.[134]

Richard I and John, 1189–1216

Richard I of England, needing money to finance his crusade, rescinded the Treaty of Falaise in return for a subsidy from the Scots, who, although still asking for the return of Cumbria and Northumbria from both Richard (1189–1199) and John (1199–1216), were refused any concessions. (John seems to have ceded the northern territories to William the Lion in return for c. £10,000, although this clause in the no-longer-extant Treaty of Norham (1209) appears to have been balanced by saying that William was a vassal of John and therefore Cumbria and the other northern territories remained English possessions). In the event, the lands were never surrendered by John as other portions of the treaty failed (marriages between the two royal families).[135]

John pursued the policy of strengthening royal control over the northern territories, particularly in the business of gathering various unpopular taxes.

However, the lack of fighting over the border settlement changed for the worse when the civil war broke out in England between King John and his nobles in 1215. The new Scottish king, Alexander II of Scotland, supported the nobles in return for their promise of the restitution of Cumbria and Northumberland to Scottish control. A Scots' army marched into Carlisle in 1216–17.[136] John drove out the Scots who then repeated the action. This situation was defused with the death of John in October 1216.[137]

Henry III, 1216–72

Henry III succeeded John as a nine-year-old but, despite this, an agreement was made between the English and Scots in 1219. The English kept the northern counties, while Alexander gained the honours of Huntingdon and Tynedale, along with Penrith and Castle Sowerby, the latter being in Inglewood Forest.

In 1237, the Treaty of York was signed, by which Alexander renounced claims to Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmorland, while Henry granted the Scottish king certain lands in the north, including manors in Cumberland. The Honour of Penrith was one of the areas of land granted to Alexander, and included, as well as the manor of Penrith, the manors of Castle Sowerby, Carlatton, Langwathby, Great Salkeld and Scotby. (The Penrith honour remained under Scots' control from 1242 until 1295).

Besides these formal agreements (and the marriage of Alexander to Henry's sister), the period was one in which local magnates and the various church establishments (abbeys, priories) co-operated across the Anglo-Scottish border. In 1292, for example, a man was hanged in Carlisle for a theft committed in Scotland. The 13th century in the Cumbria region was therefore largely peaceful.[138]

The 13th century also appears to have been a period of relative prosperity, with many of the monasteries which had been established in the 12th century beginning to flourish; most notably Furness Abbey in the south of the county which went on to become the second richest religious house in the north of England with lands across Cumbria and in Yorkshire. Wool was probably the greatest commercial asset of Cumbria at this time, with sheep being bred on the fells then wool carried along a network of packhorse trails to centres like Kendal, which became wealthy on the wool trade and gave its name to the vibrant Kendal Green colour. Iron was also commercially exploited at this time and the wide expanses of Forest became prime hunting ground for the wealthy.

Later medieval Cumbria, 1272–1485

The Scottish wars led to a hardening of the border-line as Anglo-Scottish nobles took sides with or against the English. Cross-border co-operation turned into cross-border warfare. The weakness of the English Crown's authority over the border region led to the rise of semi-independent border families, such as the Percies, the Nevilles, the Dacres and the Cliffords, who became the effective law of the land.[139] At the same time, brigandage by smaller groups became commonplace, leading to families having to fend for themselves by building peel (or pele) towers and bastle houses.

The Scottish Wars of Independence

Towards the end of the 13th century, the peace between England and Scotland was shattered at the hand of Edward I, who wished to control Scotland. In 1286 he confiscated the manors granted in 1237, and in 1292 installed John Balliol on the Scottish throne. (The other contender, Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale, accepted this situation). Edward also took direct control of Carlisle in 1292, effectively denying the city's charter and municipal status.[140] However, the outbreak of war between England and France in 1294 led Balliol to repudiate the agreement and in 1296 he invaded Cumbria (Carlisle holding out against him). Edward defeated him and took upon himself the government of Scotland; the lands of those Anglo-Scottish nobles who had backed Balliol were confiscated.

Renewed resistance came from Scotland in the form of William Wallace in 1297, (with Carlisle Castle withstanding a siege yet again), and with Robert the Bruce supporting Edward in the ending of the Wallace rising (1305). The death of Edward in 1307 and internal disputes in England under Edward II of England, allowed Robert the Bruce time to establish himself in Scotland after his having decided to renew his grandfather's claim to the Scottish throne (1306). After the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, border warfare took place mostly on the English side of the line, whereas previously it had been on the Scottish side. The Bishop of Carlisle came to private arrangements with the Scots in order to protect his lands.[141] A three-hundred-year period of regular raids and counter-raids followed which effectively undid the years of economic progress since the Harrying of the North two centuries earlier.

Two early raids of 1316 and 1322, under the leadership of Bruce were particularly damaging and were as far reaching as Yorkshire. On the second occasion, the Abbot of Furness Abbey went to meet Bruce in an attempt to bribe him into sparing his Abbey and its lands from destruction. The Scottish King accepted the bribe but continued to ransack the entire area anyway, so much so that in a tax inquisition of 1341 the land at nearby Aldingham was said to have gotten less and less in value from £53 6s 8d to just £10 and at Ulverston from £35 6s 8d to only £5.

The system of the Wardens of the Marches came into existence as a result of this First War of Scottish Independence (1296-1328) with areas on either side of the border being entrusted to 'wardens' who did what had previously been done by sheriffs in terms of military functions.[142] These were experienced military men drawn from the powerful local families (Dacres, Cliffords, Greystokes, Percies and Nevilles in Cumbria). They ran their own private armies, paid for by themselves at first, later paid for by the Crown, sometimes being offered plunder in return for their support. (Some failed to prosper in the role: the career of Andrew Harclay, 1st Earl of Carlisle, who had defended Carlisle in 1315 and became Warden of the West March, was a case in point).[143] A type of customary law grew up (March law) whereby disputes and criminal cases were dealt with by the wardens, rather than by Royal justice as elsewhere in the country. The wardens recognized special border tenant rights, in return for the supply of military service.[144]

The border 'names' (magnates) and lesser families indulged in warfare and raiding across the border, the lesser brigands often receiving protection from the greater lords. As a consequence, throughout the 14th-century, there was an increase in the building of castles by the greater magnates, and in the building of fortified houses (peel towers, mostly built during c.1350-1600; semi-fortified houses, c.1400–1600; and bastle houses, mostly built c.1540–1640) by the lesser families.[145] The authorities in Carlisle complained that the city's defences were being neglected as a result.[146]

The Church was not immune to the raiding: the monks of Holm Cultram even built a fortified church nearby at Newton Arlosh. Furness Abbey, St Bees Priory, Cartmel Priory, and, in particular, Lanercost Priory suffered : Lanercost in 1319 being described as 'waste'. (The Bishop of Carlisle, in 1337, even went as far as joining the Cliffords and Dacres on a raid to Scotland, enabling him to gain sufficient monies for him to fortify his own residence at Rose Castle). Payment of protection money was another way to stave off the Scots: Carlisle paid £200 during the 1346 invasion, for example.[147]

Edward III and the Hundred Years' War, 1327–1453

The humiliation of Bannockburn and the unsatisfactory terms, from the English point of view, of the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton of 1328 (recognising a fully independent Scotland), led the young Edward III of England to back the claims of the 'Disinherited' (those nobles who had lost lands in Scotland) in their attempt to install Edward Balliol on the throne of Scotland. The subsequent Second War of Scottish Independence lasted from 1332 to 1357, which, although boosting the credentials of Edward at home, ended in David II of Scotland retaining the throne of an independent country. During this period, the northern counties were invaded and suffered some destruction. As mentioned above, Carlisle paid protection money in 1346 to David II while on his way to the Battle of Neville's Cross (men from Cumberland fought on the English side there).

By 1337, Edward was beginning to be embroiled in what was to become the Hundred Years' War with France, with the Scots taking the side of France. It has been said that "it became a habit of the French to drag the Scots into the bigger Anglo-French dispute when they might well have stayed out."[148] Carlisle was besieged and the land round about laid waste in 1380, 1385 and 1387; in December 1388, Appleby "was almost completely destroyed"... and "never again achieved its former prosperity though it remained Westmorland's county town..." (Brougham Castle may have been destroyed in the same raid).[149] These were the years during which most of the peel towers and warning beacons were built, around the Lake District dome, chiefly in the Eden Valley, the Solway plain, the West Cumberland plain and the Kent valley.[150]

The Percies, the Nevilles, and the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses, fought between Lancastrian and Yorkist claimants to the throne of England, had some cause and effect in Cumbria, although no battle took place there. The intense rivalry between the landowners in Cumbria and elsewhere in the North fed into the factionalism at Court which was exacerbated by the mental instability of King Henry VI of England. The two main families were the Percies and the Nevilles. The Percies, a Yorkshire family, had come to prominence in Northumberland after supporting Edward I and through various marriages and confiscations of the territories of the Scottish lords. In 1375, they inherited the lands of Anthony de Luci in Egremont and Cockermouth.[151] They held the Wardenship of the East March, with the 1st Earl's eldest son holding that of the West March, which covered the north Cumbria region (1391–95).

The Nevilles had been promoted by King Richard II of England to counterbalance the growth of influence in the North of the Percies. In 1397, Ralph Neville of Raby was made Earl of Westmorland and also given the manors of Penrith and Sowerby, as well as being made sheriff of Westmorland. The Cliffords, based at Appleby and Brougham, were fearful of the rise in influence of the Neville family, (especially after the manors around Penrith had been given to them), and supported the Lancastrian Percy interest.[152]

The subsequent attempt by King Richard to lessen the power in the north of the two families, (the Crown had few estates in the North to counterbalance those of the noble families), caused both Percies and Nevilles to back Henry Bolingbroke to become King Henry IV of England in 1399. Percy power over the wardenships was restored and the Nevilles were also rewarded, although less so. The rise of the Percies was stopped, however, in 1402 when they rebelled against Henry, (partly because of the rewards garnered by the Nevilles), and they never really recovered their position thereafter. The Earl of Westmorland, who had fought against the Percies at the Battle of Shrewsbury, where the Percies were defeated, was rewarded with the wardenship of the West March. Although the Percy family still dominated Northumberland through their landed interests, (and in 1449 one of them was made Lord Egremont and another, in 1452, was made Bishop of Carlisle), in most of Cumbria the Nevilles were the greater force : the Dacres and Greystokes followed the Neville interest (Thomas Dacre, 6th Baron Dacre married the third daughter of the 1st Earl of Westmorland).

.jpg.webp)