History of rugby union

The history of rugby union follows from various football games long before the 19th century, but it was not until the middle of that century that the rules were formulated and codified. The code of football later known as rugby union can be traced to three events: the first set of written rules in 1845, the Blackheath Club's decision to leave the Football Association in 1863 and the formation of the Rugby Football Union in 1871. The code was originally known simply as "rugby football". It was not until a schism in 1895, over the payment of players, which resulted in the formation of the separate code of rugby league, that the name "rugby union" was used to differentiate the original rugby code. For most of its history, rugby was a strictly amateur football code, and the sport's administrators frequently imposed bans and restrictions on players who they viewed as professional. It was not until 1995 that rugby union was declared an "open" game, and thus professionalism was sanctioned by the code's governing body, World Rugby—then known as the International Rugby Football Board (IRFB).

Antecedents of rugby union

Although rugby football was codified at Rugby School, many rugby playing countries had pre-existing football games not dissimilar to rugby.

Forms of traditional football similar to rugby have been played throughout Europe and beyond. Many of these involved handling of the ball, and scrummaging formations. For example, New Zealand had Ki-o-rahi, Australia marn grook, Japan kemari, Georgia lelo burti, the Scottish Borders Jeddart Ba' and Cornwall Cornish hurling, Central Italy Calcio Fiorentino, South Wales cnapan, East Anglia Campball and Ireland had caid, an ancestor of Gaelic football.

The first detailed description of what was almost certainly football in England was given by William FitzStephen in about 1174–1183. He described the activities of London youths during the annual festival of Shrove Tuesday:

- After lunch all the youth of the city go out into the fields to take part in a ball game. The students of each school have their own ball; the workers from each city craft are also carrying their balls. Older citizens, fathers, and wealthy citizens come on horseback to watch their juniors competing, and to relive their own youth vicariously: you can see their inner passions aroused as they watch the action and get caught up in the fun being had by the carefree adolescents.[1]

Numerous attempts were made to ban football games, particularly the most rowdy and disruptive forms. This was especially the case in England, and in other parts of Europe, during the Middle Ages and early modern period. Between 1324 and 1667, in England alone, football was banned by more than 30 royal and local laws. The need to repeatedly proclaim such laws demonstrated the difficulty in enforcing bans on popular games. King Edward II was so troubled by the unruliness of football in London that, on 13 April 1314, he issued a proclamation banning it:

- "Forasmuch as there is great noise in the city caused by hustling over large balls from which many evils may arise which God forbid; we command and forbid, on behalf of the King, on pain of imprisonment, such game to be used in the city in the future."

In 1531, Sir Thomas Elyot wrote that English "Footeballe is nothinge but beastlie furie and extreme violence".

Football games that included ball carrying continued to be played over the century, right up to the time of William Webb Ellis's alleged invention. One form, recorded as early as 1440[2] and which persisted until the 19th century, was an East Anglian game called variously Camping, Campan, Camp-ball and Campyon which was explicitly based on carrying the ball and tossing it from player to player in order to continue the advance. According to an observer writing in 1823 (ironically the year of rugby's "invention"),

- Each party has two goals, ten or fifteen yards apart. The parties, ten or fifteen on a side, stand in line, facing each other at about ten yards' distance midway between their goals and that of their adversaries. An indifferent spectator throws up a ball the size of a cricket ball midway between the confronted players and makes his escape. The rush is to catch the falling ball. He who first can catch or seize it speeds home, making his way through his opponents and aided by his own sidesmen. If caught and held or rather in danger of being held, for if caught with the ball in possession he loses a snotch, he throws the ball (he must in no case give it) to some less beleaguered friend more free and more in breath than himself, who if it be not arrested in its course or be jostled away by the eager and watchful adversaries, catches it; and he in like manner hastens homeward, in like manner pursued, annoyed and aided, winning the notch or snotch if he contrive to carry or throw it within the goals. At a loss and gain of a snotch a recommencement takes place.[3]

19th century

Early history

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Playing football has been a long tradition in England and versions of football had probably been played at Rugby School for 200 years before three boys published the first set of written rules in 1845. The rules had always been determined by the pupils instead of the masters and they were frequently modified with each new intake. Rule changes, such as the legality of carrying or running with the ball, were often agreed shortly before the commencement of a game. There were thus no formal rules for football during the time that William Webb Ellis was at the school (1816–25) and the story of the boy "who with a fine disregard for the rules of football as played in his time, first took the ball in his arms and ran with it" in 1823 is apocryphal. The story first appeared in 1876, some four years after the death of Webb Ellis, and is attributed to a local antiquarian and former Rugbeian Matthew Bloxam. Bloxam was not a contemporary of Webb Ellis and vaguely quoted an unnamed person as informing him of the incident that had supposedly happened 53 years earlier. The story has been dismissed as unlikely since an official investigation by the Old Rugbeian Society in 1895. However, the cup for the Rugby World Cup is named the Webb Ellis trophy in his honour, and a plaque at the school commemorates the "achievement".

Rugby football has strong claims to the world's first and oldest "football club": the Guy's Hospital Football Club, formed in London in 1843, by old boys from Rugby School. Around the English-speaking world, a number of other clubs formed to play games based on the Rugby School rules. One of these, Dublin University Football Club, founded in 1854, has arguably become the world's oldest surviving football club in any code. The Blackheath Rugby Club, in London, founded in 1858 is the oldest surviving non-university/school rugby club. Cheltenham College 1844, Sherborne School 1846 and Durham School 1850 are the oldest documented school's clubs. Francis Crombie and Alexander Crombie introduced rugby into Scotland via Durham School in 1854. The first rugby club in Wales was at St David's College, Lampeter, founded in around 1850 by Rowland Williams.[4]

The Ball

Until the late 1860s, rugby was played with a leather ball with an inner-bladder made of a pig's bladder. The shape of the bladder imparted a vaguely oval shape to the ball, but they were far more spherical in shape than they are today. A quote from Tom Brown's Schooldays, written by Thomas Hughes (who attended Rugby School from 1834 to 1842), shows that the ball was not a complete sphere:

.jpg.webp)

the new ball you may see lie there, quite by itself, in the middle, pointing towards the school goal

In 1851, a football of the kind used at Rugby School was exhibited at the first World's Fair, the Great Exhibition in London. This ball can still be seen at the Webb Ellis Rugby Football Museum and it has a definite ovoid shape. In 1862, Richard Lindon introduced rubber bladders and, because of the pliability of the rubber, balls could be manufactured with a more pronounced shape. As an oval ball was easier to handle, a gradual flattening of the ball continued over the years as the emphasis of the game moved towards handling and away from dribbling. In 1892, the RFU included compulsory dimensions for the ball for the first time in the Laws of the Game. In the 1980s, leather-encased balls, which were prone to water-logging, were replaced with balls encased in synthetic waterproof materials.[5]

The schism between the Football Association and Rugby Football

The Football Association (FA) was formed at the Freemason's Tavern, Great Queen Street, on Lincoln Inn Fields, London, on 26 October 1863, with the intention of framing a code of laws that would embrace the best and most acceptable points of all the various methods of play under the one heading of football. At the beginning of the fourth meeting, attention was drawn to the fact that a number of newspapers had recently published a new version of the Cambridge rules. The Cambridge rules differed from the draft FA rules in two significant areas, namely "running with the ball" and "hacking" (kicking an opponent in the shins). The two contentious draft rules were as follows:

IX. A player shall be entitled to run with the ball towards his adversaries' goal if he makes a fair catch, or catches the ball on the first bound; but in case of a fair catch, if he makes his mark he shall not run.

X. If any player shall run with the ball towards his adversaries' goal, any player on the opposite side shall be at liberty to charge, hold, trip or hack him, or to wrest the ball from him, but no player shall be held and hacked at the same time.

At the fifth meeting, a motion was proposed that these two rules be expunged from the FA rules. Francis Maule Campbell, a member of the Blackheath Club, argued that hacking is an essential element of "football" and that to eliminate hacking would "do away with all the courage and pluck from the game, and I will be bound over to bring over a lot of Frenchmen who would beat you with a week's practice".[8] At the sixth meeting, on 8 December, Campbell withdrew the Blackheath Club, explaining that the rules that the FA intended to adopt would destroy the game and all interest in it. Other rugby clubs followed this lead and did not join the Football Association.

The formation of the first Rugby Union

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

On 4 December 1870, Edwin Ash of Richmond and Benjamin Burns of Blackheath published a letter in The Times suggesting that "those who play the rugby-type game should meet to form a code of practice as various clubs play to rules which differ from others, which makes the game difficult to play". On 26 January 1871, a meeting attended by representatives from 21 clubs was held in London at the Pall Mall restaurant.[9]

The 21 clubs and schools (all from London or the Home Counties) attended the meeting: Addison, Belsize Park, Blackheath (represented by Burns and Frederick Stokes the latter becoming the first captain of England[10]), Civil Service, Clapham Rovers, Flamingoes, Gipsies, Guy's Hospital, Harlequins, King's College, Lausanne, The Law Club, Marlborough Nomads, Mohicans, Queen's House, Ravenscourt Park, Richmond, St Paul's, Wellington College, West Kent, and Wimbledon Hornets.[11] The one notable omission was the Wasps who "In true rugby fashion … turned up at the wrong pub, on the wrong day, at the wrong time and so forfeited their right to be called Founder Members".[12]

As a result of this meeting, the Rugby Football Union (RFU) was founded. Algernon Rutter was elected as the first president of the RFU and Edwin Ash was elected as treasurer. Three lawyers, who were Rugby School alumni (Rutter, Holmes and L.J. Maton), drew up the first laws of the game; these were approved in June 1871.[9]

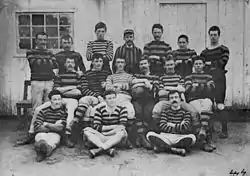

First international game

The first international football game resulted from a challenge issued in the sporting weekly Bell's Weekly on 8 December 1870 and signed by the captains of five Scottish clubs, inviting any team "selected from the whole of England" to a 20-a-side game to be played under the Rugby rules. The game was played at Raeburn Place, Edinburgh, the home ground of Edinburgh Academicals, on 27 March 1871.

This is not only the first international rugby match, but the first international of any form of football because, despite the fact that three England v Scotland fixtures had already been played according to Association Football rules at The Oval, London, in 1870 and 1871, these are not considered full internationals by FIFA as the players competing in the Scotland team were London-based players who claimed a Scottish family connection rather than being truly Scottish players.[14]

The English team wore all white with a red rose on their shirts and the Scots wore brown shirts with a thistle and white cricket flannels.[13] The England team was captained by Frederick Stokes of Blackheath, that representing Scotland was led by Francis Moncrieff; the umpire was Hely Hutchinson Almond, headmaster of Loretto College.

The game, played over two-halves, each of 50 minutes, was won by Scotland, who scored a goal with a successful conversion kick after grounding the ball over the goal line (permitting them to 'try' to kick a goal). Both sides achieved a further 'try' each, but failed to convert them to goals as the kicks were missed (see also 'Method of Scoring and Points' below).[15] Angus Buchanan of Royal High School FP and Edinburgh University RFC was the first man to score a try in international rugby.

In a return match at the Kennington Oval, London, in 1872, England were the winners.

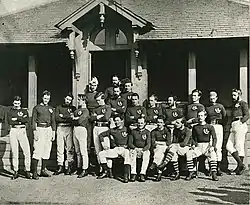

Growth within the British Empire

According to Rugby Australia, rugby football was an extremely early introduction to Australia, with games of the primitive code being played in the early to mid-19th century, and the first formal team, Sydney University Football Club being set up in 1864.[16] In 1869, Newington College was the first Australian school to play rugby in a match against the University of Sydney.[17] From this beginning, the first metropolitan competition in Australia developed, formally beginning in 1874.[16] This was organised by the Southern Rugby Union, which was administered by the rugby union at Twickenham, in England. Administration was given over to the Southern Rugby Union in 1881.

Introduction to New Zealand came later, but formal development took place around the same time as Australia. Christchurch Football Club was founded in 1863 and is regarded as the oldest rugby club in the country, with records of a football match played in August 1863.[18] however they did not 'change' to rugby football rules until after the 1868 formation of the Nelson Rugby Football Club. Rugby football was first introduced to New Zealand in 1870 by Charles John Monro, son of the then-Speaker of the House of Representatives, David Monro.[19] He encountered the game while studying at Christ's College Finchley, in East Finchley, London, England, and on his return introduced the game to Nelson College, who played the first rugby union match against Nelson football club on 14 May.[20] By the following year, the game had been formalised in Wellington, and subsequently rugby was taken up in Wanganui and Auckland in 1873 and Hamilton in 1874. It is thought that by the mid-1870s, the game had been taken up by the majority of the colony.

When Canon George Ogilvie became headmaster of Diocesan College in Cape Town, South Africa in 1861, he introduced the game of football, as played at Winchester College. This version of football, which included handling of the ball, is seen as the beginnings of rugby in South Africa. In around 1875 rugby began to be played in the Cape Colony, the following year the first rugby (as opposed to Winchester football) club was formed. Former England international William Henry Milton arrived in Cape Town in 1878. He joined the Villagers club and started playing and preaching rugby. By the end of that year, Cape Town had all but abandoned the Winchester game in favour of rugby. In 1883, the Stellenbosch club was formed in the predominantly Boer farming district outside Cape Town and rugby was enthusiastically adopted by the young Boer farmers. As British and Boer migrated to the interior, they helped spread the game from the Cape colony through the Eastern Cape, and Natal, and along the gold and diamond routes to Kimberley and Johannesburg. However, for a number of years, South African rugby would be hindered by systemic racial segregation.

Early forms of rugby football were being played in Canada from 1823 onwards, in east Canadian towns such as Halifax, Montreal and Toronto.[21] Rugby football proper in Canada dates to the 1860s. Introduction of the game and its early growth is usually credited to settlers from Britain and the British army and navy in Halifax, Nova Scotia and Esquimalt, British Columbia. In 1864, the first recorded game of rugby in Canada took place in Montreal, Quebec amongst artillery men. It is most likely that rugby got its start in British Columbia in the late 1860s or early 1870s, when brief mentions of "football" appeared in print. Canadian rugby, however, soon faced stiff competition from Canadian football.

Competition and influence on other football codes

Rugby league and association football were not the only early competitors to rugby union. In the late 19th century, a number of "national" football codes emerged around the world, including Australian rules football (originating in Victoria), Gaelic football (Ireland), and the gridiron codes: American and Canadian football.

Some of these codes took direct influence from rugby union, or rugby football, but all of these involved kicking and carrying the ball towards posts, meaning that they were in direct competition with rugby union. While American, Canadian, and Australian rules football are professional, and so competed for rugby union players' economic attentions, Gaelic football has remained staunchly amateur. The former three also use an oblong ball, superficially similar in appearance to a rugby football.

Tom Wills, the founder of Australian rules football, was educated at Rugby School. In Melbourne, in 1858, he umpired and played in several football matches using experimental rules. It was reported that "exceptions were taken … to some of the Rugby regulations",[22] and on 17 May 1859 Wills chaired a meeting to incorporate the Melbourne Football Club in which the club's rules (later the laws of Australian Football) were written down for the first time. While Wills was a fan of the rugby rules, his intentions were clear that he favoured rules that suited the drier and harder Australian fields. Geoffrey Blainey, Leonie Sandercock, Ian Turner and Sean Fagan have all written in support for the theory that rugby football was one of the primary influences on Australian rules football along with other games emanating from English public schools.[23][24]

American football resulted from several major divergences from rugby from 1869 onwards, most notably the rule changes instituted by Walter Camp, considered the "Father of American Football". Among these important changes were the introduction of the line of scrimmage and of down-and-distance rules.[25][26][27] Later developments such as the forward pass, and professionalism in American football made it diverge even further from its rugby origins.

Michael Cusack, one of the founders of the Gaelic Athletic Association, had been known as a rugby player in Ireland, and was involved with the game at Blackrock College and Clongowes Wood College. Cusack was a native Irishman who had been concerned with the decline of Irish football codes. Cusack, along with others, codified Gaelic football in 1887. The GAA retained some hostility to rugby and soccer until recent years, through its Rule 42, which prohibits the use of GAA property for games with interests in conflict with the interests of the GAA – such games are referred to by some as "garrison games" or "foreign sports".[28][29][30] In practice, the rule has only been applied to the sports of soccer, and rugby, which were perceived to be rivals to the playing of Gaelic games.[31]

Not all such codes were successful – Swedish football was created from a mixture of rugby and soccer rules, but was overtaken by soccer.

International appeal

By the end of the 19th century, rugby football and rugby union had spread far and wide. This spread was by no means confined to the British Empire.

Rugby football was an early arrival in Germany. The first German rugby team existed at Neuenheim College – now called Heidelberg College – in Heidelberg. Around 1850, the game started to attract the attention of the students. Students under the guidance of the teacher Edward Hill Ullrich were the ones who then founded the rugby department of the Heidelberger Ruderklub von 1872/Heidelberger Flaggenklub was established. (HRK 1872) in 1891, which today claims to be the oldest German rugby club.[32] The oldest still existing rugby department within a club is that of DSV 78 Hannover, formed in 1878 by Ferdinand-Wilhelm Fricke. German rugby has traditionally been centred on Heidelberg and Hanover, but has spread over the entire country in recent decades.

In the United States, rugby football-like games were being played early. For example, Princeton University students played a game called "ballown" in 1820. All of these games remained largely "mob" style games, with huge numbers of players attempting to advance the ball into a goal area, often by any means necessary.[33][34] By the 1840s, Harvard, Yale and Princeton were all playing rugby football stemming partly from Americans who had been educated in English schools.[35] However, in 1862, Yale dealt it a major blow by banning it for being too violent and dangerous. Unfortunately, American football's growth came at exactly the point at which rugby was beginning to establish itself in the States: in 1869, the first game of American football was played between Princeton and Rutgers, with rules substantially identical to rugby.[35] However, by 1882, the rules' innovations of Walter Camp, like the snap and downs, had distinguished the American game from rugby.[25]

Rugby union also reached South America early, a continent with few British colonies. The first rugby union match in Argentina was played in 1873, the game having been brought to South America by the British. In 1886 Buenos Aires Football Club played Rosario Athletic Club in Buenos Aires.[36] Early Argentinian rugby was not immune to political problems either. An 1890 game in Buenos Aires resulted in both teams, and all 2,500 spectators being arrested.[37] National president Juárez Celman was particularly paranoid after the Revolution of the Park in the city earlier in the year, and the police had suspected that the match was in fact a political meeting.[37] Rugby reached neighbouring Uruguay early, but it is disputed just how early. Cricket clubs were the incubators of rugby in South America, although rugby has survived much better in these countries than cricket has. It has been claimed that Montevideo Cricket Club (MVCC) played rugby football as early as 1865,[38] but the first certain match was between Uruguayans and British members of the MVCC in 1880.[38] The MVCC claims to be the oldest rugby club outside Europe.[39]

Rugby also appears to have been the first (non-indigenous) football code to be played in Russia, around a decade before the introduction of association football.[40] Mr Hopper, a Scotsman, who worked in Moscow arranged a match in the 1880s; the first soccer match was in 1892.[40] In 1886, however, the Russian police clamped down on rugby because they considered it "brutal, and liable to incite demonstrations and riots"[40]

The formation of the International Rugby Football Board

In 1884, England had a disagreement with Scotland over a try that England had scored but that the referee disallowed citing a foul by Scotland. England argued that the referee should have played advantage and that, as they made the Law, if they said it was a try then it was. The International Rugby Football Board (IRFB) was formed by Scotland, Ireland and Wales in 1886; but England refused to join, since they believed that they should have greater representation on the board because they had a greater number of clubs. They also refused to accept that the IRFB should be the recognised lawmaker of the game. The IRFB agreed that the member countries would not play England until the RFU agreed to join and accept that the IRFB would oversee the games between the home unions. England finally agreed to join in 1890. In 1930, it was agreed between the members that all future matches would be played under the laws of the IRFB. In 1997, the IRFB moved its headquarters from London to Dublin and a year later it changed its name to the International Rugby Board (IRB); in 2014, it changed its name again to the current World Rugby (WR).

Evolution of the laws of the game

Changes to the laws of the game have been made at various times and this process still continues day

Number of players

The number of players on the field for each team was reduced from 20 to 15 a side in 1877.[41]

Method of scoring and points

Historically, no points at all were awarded for a try, the reward being to "try" to score a goal (to kick the ball over the cross bar and between the posts). Modern points scoring was introduced in the late 1880s,[42] and was uniformly accepted by the Home Nations for the 1890/91 season.[42]

The balance in value between tries and conversions has changed greatly over the years. Until 1891, a try scored one point, a conversion two. For the next two years, tries scored two points and conversion three. In 1893, the modern pattern of tries scoring more was begun, with three points awarded for a try, two for a kick. The number of points from a try increased to four in 1971[42] and five in 1992.[43]

Penalties have been worth three points since 1891 (they previously had been worth two points). The value of the drop goal was four points between 1891 and 1948, three points at all other times.[42]

Before the 1937–38 northern hemisphere season, whenever a team chose to take a penalty kick, the offending team formed up at the point of the penalty, with the kicker retreating. Ever since, penalty kicks have been taken from the spot of the penalty, with the offending team required to retreat at least 10 yards toward their own try line.[44]

The goal from mark was made invalid in 1977, having been worth three points, except between 1891 and 1905 when it was worth four.[43] The field goal was also banned in 1905 after previously being worth 4.[43]

The defence was originally allowed to attempt to charge down a conversion kick from the moment the ball was placed on the ground, generally making it impossible for the kicker to place the ball himself and make any kind of a run-up. As a result, teams had a designated placer, typically the scrum-half, who would time the placement to coincide with the kicker's run-up. In 1958, the law governing conversions changed to today's version, which allows the kicker to place the ball and prohibits the defence from advancing toward the kicker until he begins his run-up.[45]

The beginning of rugby sevens

Rugby sevens was initially conceived by Ned Haig a Jedburgh butcher who moved to Melrose and David Sanderson as a fund-raising event for a local club in 1883. The first ever sevens match was played at the Greenyards, the Melrose RFC ground, where it was well received. Two years later, Tynedale was the first non-Scottish club to win one of the Borders Sevens titles at Gala in 1885.[46]

Despite sevens' popularity in the Scottish Borders, it did not catch on elsewhere until after WWI, in the 1920s and 1930s.[47] The first sevens tournament outside Scotland was the Percy Park Sevens at North Shields in north east England in 1921.[46] Because it was not far from the Scottish Borders, it attracted interest from the code's birthplace, and the final was contested between Selkirk (who won) and Melrose RFC (who didn't).[46] In 1926, England's major tournament, the Middlesex Sevens was set up by Dr J.A. Russell-Cargill, a London-based Scot.[46]

The schism between union and league

It is believed that Yorkshire inaugurated amateurism rules in 1879; their representatives along with Lancashire's, are credited with formalising the RFU's first amateur rules in 1886. Despite popular belief, these Northern bodies were strong advocates of amateurism, leading numerous crusades against veiled professionalism. However, conflict arose over the controversy regarding broken time, the issue of whether players should receive compensation for taking time off work to play. The northern clubs were heavily working class, and thus, a large pool of players had to miss matches due to working commitments, or forego pay to play rugby. In 1892, charges of professionalism were laid against rugby football clubs in Bradford and Leeds, both in Yorkshire, after they compensated players for missing work, but these were not the first allegation towards these northern bodies, nor was it unheard of for southern clubs to be faced with similar circumstances. The RFU became concerned that these broken time payments were a pathway to professionalism.

This was despite the fact that the Rugby Football Union (RFU) was allowing other players to be paid, such as the 1888 England team that toured Australia, and the account of Harry Hamill of his payments to represent New South Wales (NSW) against England in 1904.

In 1893, Yorkshire clubs complained that southern clubs were over-represented on the RFU committee and that committee meetings were held in London at times that made it difficult for northern members to attend. By implication, they were arguing that this affected the RFU's decisions on the issue of "broken time" payments (as compensation for the loss of income) to the detriment of northern clubs, who made up the majority of English rugby clubs. The professional Football League had been formed in 1888, comprising 12 association football (soccer) clubs from northern England, and this may have inspired the northern rugby officials to form their own professional league.

On 29 August 1895, at a meeting at the George Hotel, Huddersfield, 20 clubs from Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cheshire decided to resign from the RFU and form the Northern Rugby Football Union, which from 1922 was known as the Rugby Football League. In 1908, eight clubs in Sydney, Australia, broke away from union and formed the New South Wales Rugby League. The dispute about payment was one which at the time was also affecting soccer and cricket. Each game had to work out a compromise; rugby's stance was the most radical. Amateurism was strictly enforced, and anyone accepting payment or playing rugby league was banned. It would be a century before union legalised payments to players and would allow players who had played a game of league, even at an amateur level, to play in a union game.

20th century

Summer Olympics

Pierre de Coubertin, the revivor of the Olympics, introduced rugby union to the Summer Olympics at the 1900 games in Paris. Coubertin had previous associations with the game, refereeing the first French domestic championship as well as France's first international. France, the German Empire and Great Britain all entered teams in the 1900 games (Great Britain was represented by Moseley RFC),[48] Germany by the SC 1880 Frankfurt.[49] France won gold defeating both opponents. The rugby event drew the largest crowd at that particular games. Rugby was next played at the 1908 games in London. A Wallaby team, on tour in the United Kingdom, took part in the event, winning the gold, defeating Great Britain who were represented by a team from Cornwall.[48] The United States won the next event, at the 1920 Summer Olympics, defeating the French. The Americans repeated their achievement at the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, again defeating France. Though rugby had attracted bigger crowds than the track and field events in 1924, it was dropped from next Games and has not been included since.

In October 2009, the International Olympic Committee voted to return a form of rugby to the Olympics, with rugby sevens contested for the first time in Rio de Janeiro in 2016.[50]

1900s and early 1910s

Between 1905 and 1908, all three major Southern Hemisphere rugby countries sent their first touring teams to the Northern Hemisphere: New Zealand in 1905, followed by South Africa in 1906 and then Australia in 1908. All three teams brought new styles of play, fitness levels and tactics,[51] and were far more successful than critics had expected.[52] The New Zealand 1905 touring team performed a haka before each match, leading Welsh Rugby Union administrator Tom Williams to suggest that Wales player Teddy Morgan lead the crowd in singing the Welsh National Anthem, Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau, as a response. After Morgan began singing, the crowd joined in: the first time a national anthem was sung at the start of a sporting event.[53] In 1905, France played England in its first international match.[51]

World War I

The horrific bloodshed and suffering of World War I affected all sports, including rugby union.

The Five Nations Championship was suspended in 1915 and was not resumed until 1920, though in Britain in 1919, a tournament was arranged between Forces teams; it was won by the New Zealand Army.

One hundred and thirty-three international players were killed during the conflict. The Queensland Rugby Union was disbanded after the war and was not reformed until 1929. NSW took responsibility for rugby union in Australia until the formation of the Australian Rugby Union, now known as Rugby Australia, in 1949.

1920s

Centenary of rugby

As 1923 approached, there were discussions of a combined England and Wales XV playing a Scottish-Irish team in celebration of when William Webb Ellis picked up the football and ran with it in 1823. The planned game was controversial in that there was a disagreement over whether it should be held at Rugby School, or be played at Twickenham, where an obviously larger crowd could witness the match. In the end, the match was taken to Rugby School.[54]

Formation of FIRA

For many years, there had been suspicion that the governing body of French rugby union, the French Rugby Federation (FFR) was allowing the abuse of the rules on amateurism, and in 1931 the French Rugby Union was suspended from playing against the other IRFB nations. As a result, Fédération Internationale de Rugby Amateur (FIRA) was founded in 1932.[55]

In 1934, the Association was formed at the instigation of the French. It was designed to organise rugby union outside the authority of the International Rugby Football Board (as it was known at the time). The founder members were Italy, Romania, Netherlands, Catalonia, Portugal, Czechoslovakia, and Sweden.[55][56] In the 1990s, the organisation recognised the IRB as the governing body of rugby union worldwide and in 1999 changed its name to FIRA – Association of European Rugby, an organisation to promote and rule over rugby union in the European area. The organisation changed its name again in 2014 to Rugby Europe.

Until its eventual merger with the IRB, Rugby Europe was the most multinational rugby organisation in the world, partly because the IRB had concentrated on the Five Nations, Tri Nations, and from 1987 the Rugby World Cup, competitions. Rugby Europe has generally been a positive force in spreading the sport beyond the English-speaking world.[55]

Interesting times – 1930s

In 1931, Lord Bledisloe, the Governor-General of New Zealand, donated a trophy for competition between Australia and New Zealand. The Bledisloe Cup became one of the great rivalries in international rugby union.

Following the suspension of the French Rugby Federation (FFR) in 1931, many French players turned to rugby league, which soon became the dominant game in France, particularly in the south west of the country.

In 1934, the Federation Internationale de Rugby Amateur (FIRA) was formed at the instigation of the French. It was designed to organise rugby union outside the authority of IRB. In the 1990s, the organisation recognised the IRB as the governing body of rugby union worldwide and later changed its name twice—in 1999 to FIRA—Association of European Rugby, and in 2014 to Rugby Europe. Today, Rugby Europe promotes and rules over rugby union in the European area.

In 1939, the FFR was invited to send a team to the Five Nations Championship for the following season, but when war was declared, international rugby was suspended. Eighty-eight international rugby union football players were killed during the conflict.

World War II

During World War II, the RFU temporarily lifted its ban on rugby league players, many of whom played in the eight "internationals" between England and Scotland that were played by Armed Services teams under the rugby union code. The authorities also allowed the playing of two "Rugby League v Rugby Union" fixtures as fund-raisers for the war effort. The rugby league team (which included some pre-war professionals) won both matches, which were held under union rules.

After the defeat of France in 1940, the French Rugby Union authorities worked with the German collaborating Vichy regime to re-establish the dominance of their sport. Rugby union's amateur ethos appealed to the occupier's view of the purity of sport. Rugby league, along with other professional sports, was banned. Many players and officials of the sport were punished, and all of the assets of the Rugby League and its clubs were handed over to the Union. The consequences of this action reverberate to this day, as these assets were never returned. Although the ban on rugby league was lifted, it was prevented from calling itself "rugby" until the mid-1980s, having to use the name Jeu à Treize (Game of Thirteen) in reference to the number of player in a rugby league side.[57]

Post-War, late 1940s and 1950s

In 1947, the Five Nations Championship resumed with France taking part.

In 1948, the worth of a drop goal was reduced from 4 points to 3 points.

In 1949, the Australian Rugby Union was formed and took over the administration of the game in Australia from the New South Wales Rugby Union.

In 1958, long after the legend of William Webb Ellis had become engrained in rugby culture, Ross McWhirter managed to relocate his grave "le cimetière du vieux château" at Menton in Alpes Maritimes (has since been renovated by the French Rugby Federation).

1960s

During the 1960s, there was stronger and stronger condemnation of the racist apartheid regime in South Africa. This racism extended to rugby union, and the sport soon found itself involved in its most serious controversy since 1895. By 1969, the Halt All Racist Tours campaign group had been set up in New Zealand.

1970s

1970 saw the invention of mini rugby, a form of the game still used to train children.

In 1971, Scotland appointed Bill Dickinson as their head coach, after years of avoidance, as it was their belief that rugby should remain an amateur sport. The 1971 Springbok tour to Australia was famous for its political protests against South Africa's apartheid system. The 1970s were a golden era for Wales with the team capturing five Five Nations titles and dominating the Lions selections throughout the decade. In the middle of the decade, after overseeing the rise in popularity of rugby union in the United States, members' bodies met in Chicago in 1975 and formed the United States of America Rugby Football Union, today known as USA Rugby.

1980s

The 1981 Springbok Tour to New Zealand was also marked by political protests and is still referred to by New Zealanders as The Tour. The tour divided New Zealand society and rugby lost some of its prestige, which was not restored until New Zealand won the inaugural 1987 Rugby World Cup. In 1983, the WRFU (Women's Rugby Football Union) was formed, with 12 inaugural clubs, the body being responsible for women's rugby in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. In 1984 the Wallabies completed their first grand slam, defeating all four nations of the British Isles, and announcing their emergence as a power in world rugby.

The Rugby World Cup

.jpg.webp)

2007 Rugby World Cup

The first Rugby World Cup was played in 1987. New Zealand hosted the tournament, with some games, including both semi-finals, being played in Australia. The All Blacks defeated France in the final.

In 1991, England hosted the second tournament, losing to Australia in the final.

The World Cup of 1995 proved to be a turning point for the game. The competition was held in South Africa, newly readmitted from international exile. Giant wing Jonah Lomu scored four tries for the All Blacks against England. South Africa, who had not been allowed to compete in the first two tournaments, won the final, beating the All Blacks 15–12, the winning score coming from a drop-goal by Joel Stransky. The tournament became a point of reconciliation for the new South Africa, as South African President Nelson Mandela, dressed in a Springbok jersey, which was long a symbol of apartheid, bearing the name and number six of South Africa's captain François Pienaar, handed him the William Webb Ellis Trophy.

The 1999 Rugby World Cup was held in Wales and was won by Australia, who defeated France in the final after the latter had come from behind to record a shock win against tournament favourites, the All Blacks, at the semi-final stage.

In 2003, Australia hosted the tournament and reached the final for the third time. In a closely fought game, which went into extra time, Australia narrowly lost to England, thanks to a last-minute drop goal by Jonny Wilkinson.

France was the host nation for the 2007 Rugby World Cup, though several games were played in Edinburgh and Cardiff, and France played its quarter-final in Wales, against the All Blacks, who had started the tournament as odds-on favourites. In a repeat of 1999, France gained a shock win, consigning the favourites to their worst result in World Cup history. France went on to lose against England at the semi-final stage. England, in turn, lost in the final to the Springboks, who equalled Australia's record of two World Cup wins.

The breakthrough team in that competition was Argentina who started with a narrow win over France in the opener, and defeated Ireland to finish atop their pool. They lost in the semifinals to South Africa, but rebounded with a comprehensive win over France in the third-place game. This result led to calls to include the Pumas in one of the major hemispheric national team competitions, such as the Six Nations or Tri Nations. Ultimately, it was decided that the Pumas would be steered toward a future place in the Tri Nations, and they would join that competition in 2012, at which time it was renamed The Rugby Championship.

Rugby union and apartheid

Even before the apartheid laws were passed in South Africa after 1948, sporting teams going to South Africa had felt it necessary to exclude non-white players. In 1906, the South Africans objected to the selection of black England international James Peters when he turned out for Devon; but were persuaded to play by officials. Though, when England faced South Africa later in the tour, Peters was not selected.[58] New Zealand rugby teams in particular had done this, and the exclusion of George Nepia and Jimmy Mill from the 1928 All Blacks tour,[59][60] and the dropping of Ranji Wilson from the New Zealand Army team nine years before that,[61] had attracted little comment at the time. However, in 1960 international criticism of apartheid grew in the wake of The Wind of Change speech and the Sharpeville massacre.[62]

From this point onward, the Springboks were increasingly the target of international controversy and protest.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1960 | An All Blacks team with no Maori players toured South Africa, despite a campaign based on the slogan of "No Maoris, No Tour", and a 150,000 signature petition opposing it.[63] |

| 1969 | Throughout the 1969 Springbok tour of Great Britain and Ireland, large anti-apartheid demonstrations were a feature, and many matches had to be played behind barbed wire fences. |

| 1971 | The Springbok Rugby Union tour of Australia is marked by protests. |

| 1976 | Twenty-eight nations boycott the 1976 Summer Olympics in protest against the International Olympic Committee's refusal to ban New Zealand from the games for defying the IOC's ban on sporting contact with South Africa. |

| 1981 | The 1981 tour of New Zealand went ahead in defiance of the Gleneagles Agreement. The tour and the massive civil disruption in New Zealand had ramifications far beyond rugby. |

| 1984 | In the 1984 England rugby union tour of South Africa, only Ralph Knibbs of Bristol refused to tour for political reasons. |

| 1985 | A planned All Black tour of South Africa was stopped by the New Zealand High Court. A rebel tour took place the next year by a team known as the Cavaliers. |

| 1989 | A World XV sanctioned by the International Rugby Board went on a mini-tour of South Africa. All traditional rugby nations bar New Zealand supplied players to the team with ten Welshmen, eight Frenchmen, six Australians, four Englishmen, one Scot and one Irishman. |

Professionalism

On 26 August 1995, the International Rugby Board declared rugby union an "open" game and thus removed all restrictions on payments or benefits to those connected with the game. It did this because of a committee conclusion that to do so was the only way to end the hypocrisy of shamateurism and to keep control of rugby union.

The threat to amateur rugby union was especially large in Australia where Super League was threatening to entice players to rugby league with large salaries.[64] SANZAR was formed in 1995 by the New Zealand, Australian and South African Rugby Unions to try to counter the Super League threat.[65] SANZAR proposed a provincial competition with teams from all three countries. This competition became the Super 12 (later Super 14 in 2005, and Super Rugby since 2011). The SANZAR proposals also included an annual competition between each country's Test teams, the Tri Nations Series. They were eventually able to get backing for the competition from Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation, with a contract totalling $US 550 million for ten years of exclusive TV and radio broadcasting rights. The deal was signed during the 1995 Rugby World Cup and revealed at a press conference on the eve of World Cup final.[66]

SANZAR's proposals were under serious threat from a Sydney-based group called the World Rugby Corporation (WRC). WRC was formed by lawyer Geoff Levy and former Wallaby player Ross Turnbull. Both wanted a professional worldwide rugby competition funded by Kerry Packer, who had already developed professional cricket.[67] At one point the WRC had a majority of the All Blacks and Wallaby teams signed up to their competition. In addition to this the Springboks had also signed the WRC contracts but had decided not to hand them over and instead signed up with the South African Rugby Union.[68] The players had been told they would never play for their country again if they committed to the WRC.[69] Most of the All Blacks then followed their Springbok counterparts by signing with their Union. The Australians, realising that without the New Zealanders and South Africans WRC's proposal could not succeed, relented and signed for the Australian Rugby Union.[70]

The Heineken Cup was formed in 1995 as a competition for 12 European clubs. By the time it was replaced in 2014 by the European Rugby Champions Cup, it included teams from all of the Six Nations countries; the current Champions Cup still involves these countries.

Professionalism opened the door for the emergence of a new rugby generation in Italy. The Italian domestic leagues had attracted a degree of tax relief in the 1990s, and were able to attract both strong corporate sponsorship and also high quality coaches and players with recent Italian heritage from Australia and Argentina. These improvements led to a national team capable of competing with the national teams of the British Isles, proven by a famous victory against Ireland in 1995. Lobbying was successful to have Italy included in the century-old tournament for the top European rugby nations which became the Six Nations championship in 2000.

A key benefit that professionalism brought to rugby union as a whole was the elimination of the constant defection of union players who were attracted to the money of rugby league. The rugby union authorities of the time also hoped that as players could now play in either code, in the long term most of the sponsorship and interest would gravitate away from league to the more international game of union. However, rugby union has not managed to lure away more than a handful of elite players from rugby league, as the two codes have become quite different over the decades of separation in both culture and in aspects of play. The preferred body type and skill sets of players differ, especially in the play of the forwards. With access to players of different types, some more suited to one code and some to the other, some English rugby union clubs have even formed partnerships with a rugby league club which plays in the premier rugby league competitions – the most notable example being Harlequins with London Broncos (formerly Harlequins Rugby League), and between Wigan Warriors and Saracens.

In some countries rugby union's administration and structure have not developed along with its professionalism. In Australia the constant flow of rugby union juniors to rugby league clubs has slowed, but Australian rugby union has failed to successfully promote a club or franchise league below the elite level. With professional club games every weekend, Australian rugby league has maintained its dominance over union, especially in its traditional heartlands of New South Wales and Queensland.

The many smaller unions across the globe have struggled both financially and in playing terms to compete with the major nations since the start of the open era. In England whilst some teams flourished in the professional era others such as Richmond, Wakefield, Orrell, Waterloo and London Scottish found the going much harder and have either folded or dropped down to minor leagues. In the other Home Nations, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, the professional era had a traumatic effect on the traditional structure of the sport, which had been based around local clubs. Professional rugby in these three countries is now regionally based. In Ireland, each of the four traditional provinces supports one professional team. Scotland currently has two regional teams, each based in one of the country's two largest cities. Wales adopted a regional franchise model, originally with five teams but now with four. These three countries have a joint professional competition, originally known as the Celtic League. In 2010, two Italian super-regional teams joined the competition, which was renamed the Pro12, and in 2017, two South African franchises joined the Pro14 competition.

21st century

Alterations to the laws of rugby union were trialled by students of Stellenbosch University in South Africa in 2006, and were adopted in competitions in Scotland and Australia since 2007, though only a few of the rules were universally adopted. The law variations are an attempt to make rugby union easier to understand by referees, fans and players, but the laws were controversial and far from being endorsed by all members of these groups.[71] After a number of trials around half of the proposed changes were permanently added to the laws of the sport.

In 2012, the Tri Nations was expanded to include Argentina, with the competition being renamed The Rugby Championship. The competition's organiser, now known as SANZAAR after the Argentine Rugby Union became a full member in 2016, has also expanded Super Rugby in the 21st century, first expanding from 12 to 14 teams in 2006, then to 15 teams in 2011, and most recently to 18 teams in 2016. The last of these expansions spread Super Rugby's geographic scope outside of its founding countries (South Africa, Australia, New Zealand) for the first time, adding new teams in Argentina and Japan.

In 2014, the European club competition structure was revamped. The top-level Heineken Cup and second-level European Challenge Cup were respectively replaced by the European Rugby Champions Cup and European Rugby Challenge Cup. The most significant changes to the structure were a reduction in the number of clubs taking part in the top competition from 24 to 20, plus the introduction of a play-off to determine one place in the Champions Cup.

Scoring

The scoring system used in rugby has changed many times over the years. In the original games completing a "touch down" allowed the team to "try" a kick at goal. This is the derivation of the word "try". Prior to 1890, games were won by goals scored. A goal was awarded for a successful conversion after a try, a drop goal or from a goal from mark. If the game was drawn, then unconverted tries were tallied to give a winner. This system led to score lines more akin to association football with far more games resulting in draws than are experienced in the modern game. One of the first tasks undertaken by the International Rugby Football Board, formed in 1886, was to introduce a standard point scoring system. One point was awarded for a try, two points for a successful kick at goal after scoring a try (a conversion) and three points for a dropped goal or for a penalty goal. Most of the changes have been to increase the value of tries compared to goals (conversions, penalties, dropped-goals, and goals from mark) in order to promote positive, attacking play. Field goals were considered valid methods of scoring until the RFU and IRFB banned them in 1905 with the value at abolition being 4 points.[72]

| Date | Try | Conversion | Penalty | Dropped goal | Goal from mark | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1871–1875 | no score | 1 goal | 1 goal | 1 goal | N/A | RFU systems prior to inception of the International Rugby Football Board (IRFB) |

| Match decided by a majority of goals | ||||||

| 1876–1885 | 1 try | 1 goal | 1 goal | 1 goal | N/A | |

| Match decided by a majority of goals, or if the number of goals is equal by a majority of tries | ||||||

| 1886–1891 | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points | 3 points | N/A | Scoring systems after the administration of the game was taken over by the IRFB – now known as World Rugby |

| 1891–1894 | 2 points | 3 points | 3 points | 4 points | 4 points | |

| 1894–1904 | 3 points | 2 points | 3 points | 4 points | 4 points | |

| 1905–1947 | 3 points | 2 points | 3 points | 4 points | 3 points | |

| 1948–1970 | 3 points | 2 points | 3 points | 3 points | 3 points | |

| 1971–1977 | 4 points | 2 points | 3 points | 3 points | 3 points | |

| 1977–1991 | 4 points | 2 points | 3 points | 3 points | N/A | |

| 1992–present | 5 points | 2 points | 3 points | 3 points | N/A | |

Timeline of the foundation of national rugby unions

The first national rugby union was the Rugby Football Union, founded in England in 1871. This was followed over the next decade by the home nations of Scottish Football Union (1873, later SRU), Irish Rugby Football Union (1879) and Welsh Rugby Union (1881). The French Federation (1919) and most recent addition to the 6 Nations Italy (1928).

In the southern hemisphere the traditional rugby powers of South Africa and New Zealand formed their Unions before the end of the 19th century. The white South African Rugby Board merged with the non-racial South African Rugby Union in 1992 following the fall of apartheid. In Australia the third traditional southern rugby power, the Southern Rugby Union (later the New South Wales Rugby Union) and the Northern Rugby Union (later the Queensland Rugby Union) were formed in 1874 and 1883 respectively, before eventually helping form the Australian Rugby Union, now known as Rugby Australia, in 1949. Recent addition to The Rugby Championship Argentina founded its union in 1899.

Other foundations of note include nations that have featured in several or indeed all of the Rugby World Cups today including Fiji (1913), Tonga (1923), Samoa (1923), Japan (1926), Canada (1965) and USA (1975).

Some of the pre-1925 foundations such as Rhodesia/Zimbabwe (1895), Germany (1900), Ceylon/Sri Lanka (1908), Morocco (1916), Malaya/Malaysia (1921), Catalonia (1922, later disbanded by Francisco Franco), Spain (1923) and Kenya (1923) are second and third tier nations.

Many other governing bodies have been set up in recent years, with the most recent being Jordan (2007), Ecuador (2008), Turkey (2009) and the United Arab Emirates (2010).

Important international competitions

- 1883: First Home Nations Championship between England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales.

- 1900: Rugby union features at the 1900 Olympics – and finishes in the 1924 Olympics.

- 1910: The Home Nations Championship becomes the Five Nations Championship when France joins.

- 1930: European Cup, outside the Five Nations, but interrupted by WWII.

- 1951: South American Rugby Championship commences.

- 1952: European Cup restarts.

- 1981: Rugby union at the Maccabiah Games commences.

- 1982: Pacific Tri-Nations between Tonga, Fiji and Samoa

- 1987: First Rugby World Cup.

- 1991: First Women's Rugby World Cup, though the competition would not be operated by World Rugby until 1998, and its pre-1998 winners would not be officially recognised by World Rugby until 2009.

- 1995: PARA Pan American Championship

- 1996: The Tri Nations Series begins between Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.

- 1996 The Women's Home Nations Championship begins.

- 1998: Rugby sevens at the Commonwealth Games and Asian Games commences. Also, the first Women's Rugby World Cup to be officially sanctioned by the IRB takes place.

- 1999:

- World Rugby Sevens Series commences as IRB Sevens World Series.

- The Women's Home Nations Championship becomes the Women's Five Nations Championship when France joins.

- 2000:

- The Five Nations becomes the Six Nations Championship when Italy joins.

- Africa Cup commences.

- 2002: The Women's Five Nations Championship becomes the Women's Six Nations Championship when Spain join full-time.

- 2003: Churchill Cup commences with Canada, the US, and England Saxons (England "A") as permanent participants and one invited team (later three).

- 2004: CAR Development Trophy (Africa) commences.

- 2006: Pacific Nations Cup/Pacific Rugby Cup and IRB Nations Cup commence.

- 2007: The (men's) Six Nations committee formally takes over the Women's Six Nations; Spain is replaced with Italy to align the men's and women's competitions.

- 2008: Asian Five Nations founded. The IRB folds its former under-19 and under-21 world championships into a new two-tiered under-20 structure, with the competitions now known as the World Rugby Under 20 Championship and World Rugby Under 20 Trophy.

- 2011: The Churchill Cup holds its final edition. From 2012 on, the US and Canada have been included in the WR international tour calendar.

- 2012: The Tri Nations adds Argentina, and is renamed The Rugby Championship.[73]

- 2013: The World Rugby Women's Sevens Series commences as the IRB Women's Sevens World Series.

- 2016:

- The Americas Rugby Championship is established in its current "Six Nations" format, with Argentina's "A" side, now known as Argentina XV, joined by the senior sides of Brazil, Canada, Chile, Uruguay and the USA.

- The first Olympic sevens tournaments took place.

- 2018: Women's sevens will make its Commonwealth Games debut.

List of Rugby World Cup Finals

For more details see the article Rugby World Cup

- 1987: New Zealand defeated France 29–9 at Eden Park, Auckland, in the first Rugby World Cup, held in New Zealand and Australia.

- 1991: Australia defeated England 12–6 at Twickenham, London, in the second Rugby World Cup, held in the British Isles and France.

- 1995: South Africa defeated New Zealand 15–12 (after extra time) at Ellis Park, Johannesburg in the third Rugby World Cup, held in South Africa.

- 1999: Australia defeated France 35–12 at the Millennium Stadium, Cardiff in the fourth Rugby World Cup, held in Wales with matches also being played in England, Scotland, Ireland and France.

- 2003: England defeated Australia 20–17 (after extra time) at Stadium Australia, Sydney in the fifth Rugby World Cup, held in Australia.

- 2007: South Africa defeated England 15–6 at Stade de France, Saint-Denis in the sixth Rugby World Cup, held in France with matches also being played in Scotland and Wales.

- 2011: New Zealand defeated France 8–7 at Eden Park, Auckland, in the seventh Rugby World Cup, held in New Zealand.

- 2015: New Zealand defeated Australia 34–17 at Twickenham, London, in the eighth Rugby World Cup, held in England with matches also being played in Wales.

- 2019: South Africa defeated England 32–12 at Yokohama, Japan, in the ninth Rugby World Cup, held in Japan.

Notable games

- 1871: First recognised international match, played between England and Scotland at Raeburn Place.[74]

- 1905: Wales narrowly beat the first touring New Zealand team, dubbed 'The Game of the Century'.[75][76]

- 1973: The Barbarians defeat the All Blacks at Cardiff Arms Park[77]

- 1978: Irish provincial side Munster defeat the All Blacks 12–0 at Thomond Park. It is the All Blacks only defeat on the 1978 tour.[78]

- 1999: France upsets the heavily favoured All Blacks in the 1999 Rugby World Cup semi-finals.[79]

- 2000: New Zealand narrowly defeats Australia at Stadium Australia in front of a world-record crowd of 109,874.[80]

International debuts of Tier 1 & 2 nations

- 1871: Scotland and England after Scottish invitation.

- 1875: Ireland.

- 1881: Wales

- 1891: South Africa (against a British Isles side.)

- 1899: Australia (against a British Isles side.)

- 1903: New Zealand

- 1906: France (against New Zealand).

- 1910: Argentina (against a British Isles side.)

- 1912: United States (against Australia.)

- 1919: Romania.

- 1924: Samoa and Fiji (against one another) and also Tonga (against Fiji in a different match.)

- 1929: Italy (against Spain).

- 1932: International debut of Canada and Japan, against one another.

See also

- England v Scotland representative football matches (1870–1872) First ever international Association Football match, organised by the Football Association.

- List of oldest rugby union competitions

- McGill University – Athletics The inventions of North American football, hockey, rugby and basketball are all related to McGill in some way. In 1865, the first recorded game of rugby in Canada (and North America) occurred in Montreal, between British army officers and McGill students.

Notes

- Alsford, Stephen. "Florilegium Urbanum". Retrieved 5 April 2006.

- The first ever English-Latin dictionary, Promptorium parvulorum (ca. 1440), offers the following definition of camp-ball: "Campan, or playar at foott balle, pediluson; campyon, or champion"

- Moor, Edward, Suffolk Words and Phrases: Or, An Attempt to Collect the Lingual Localisms. London: R. Hunter,(1823).

- "Celebrating the roots of Welsh rugby". Welsh Rugby Union. 22 March 2016.

- Price, Oliver (5 February 2006). "Blood, mud and aftershave". The Observer. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- Shortell, Peter. "Hacking – a history (membership needed)". Cornwall Referees Society. Archived from the original on 3 March 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- Marindin, Francis. "Ebenezer Cobb Morley". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- Staff.World Rugby Chronology Archived 21 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine,World Rugby Museum Archived 14 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2008-11-10. See 1 December 1863 – 5th FA meeting."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Dunning, Eric; Sheard, Kenneth (2005), Barbarians, Gentlemen and Players: A Sociological Study of the Development of Rugby Football (2nd, illustrated, revised ed.), Psychology Press, pp. 105–106, ISBN 978-0-7146-5353-2

- Lewis, Steve (2008). One Among Equals. London: Vertical Editions. p. 9.

- RFU Museum staff, World Rugby 1871–1888, RFU, archived from the original on 23 February 2013, retrieved 23 February 2013

- "History 1867–1930 London Wasps". Wasps.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 July 2014.

- Glasgow Herald (Glasgow, Scotland), Tuesday, 28 March 1871; Issue 9746

- "The birth of international football: England v Scotland, 1870". lordkinnaird.com. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- Richards, Huw (2007). A Game for Hooligans. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84596-255-5.

- History of the ARU Archived 24 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Hickie, Thomas V. (1998). A Sense of Union – A History of the Sydney University Football Club. Playright Publishing. p. 22.

- Early rugby in Christchurch on Christchurch City Council

- Wright-St Clair, Rex. "Monro, David 1813–1877". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- "New Zealand Rugby". activenewzealand.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- Marsh, James H. (1999). The Canadian Encyclopedia. p. 2050. ISBN 0-7710-2099-6.

- The Argus 16 May 1859

- Davis, Richard (1991). Irish and Australian Nationalism: the Sporting Connection: Football & Cricket. 3. Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies Bulletin. pp. 49–50.

- O'Dwyer, B. W. (1989). The Shaping of Victorian Rules Football. 60. Victorian Historical Journal.

- "Camp and His Followers: American Football 1876–1889" (PDF). The Journey to Camp: The Origins of American Football to 1889. Professional Football Researchers Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- "The History of Football". The History of Sports. Saperecom. 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- "NFL History 1869–1910". NFL.com. NFL Enterprises LLC. 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- "A long way from Dublin's bloody past". BBC News. 3 February 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- Ward, Paul (2004). Britishness since 1870. London: Routledge. p. 79.

- Coogan, Tim Pat (2000). Wherever the Green Is Worn. New York: Palgrave. p. 179.

- "The odd couple: Soccer and GAA remain bitter enemies". Irish Independent. 24 March 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- Bath, Richard (1997), p.67

- "No Christian End!". The Journey to Camp: The Origins of American Football to 1769. Professional Football Researchers Association. Archived from the original on 4 April 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- Meacham, Scott (2006). "Old Division Football, The Indigenous Mob Soccer of Dartmouth College (pdf)" (PDF). dartmo.com. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- Bath (1977) p77

- Bath (1997) pp. 62–63

- Cotton (1984), p.29

- Richards (2007), p.54

- Montevideo Cricket Club in history Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, p5, retrieved 31 August 2009

- Riordan (1977), p.22

- Griffiths (1987), 1:4.

- Griffiths (1987), x

- "Scoring through the ages rugbyfootballhistory.com". rugbyfootballhistory.com. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- Richards, Huw (16 March 2018). "England and Scotland served up 'spectacular' Calcutta Cup to usher in TV era". ESPN (UK). Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Griffiths, John (2 August 2010). "The players with the most Test wins, Welshmen in Italy and the conversion kick". Ask John. ESPN Scrum. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- Bath (2007), p.82

- Starmer-Smith (1986), p.60

- Barker, Philip. "Rugby World Cup Stirs Olympic Memories". British Olympic Association. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- "Rugby im 80" (in German). sc1880.de. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- "Golf & rugby voted into Olympics". BBC. 9 October 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- Godwin 1981, p. 18

- Thomas 1954, p. 27 "When they arrived in this country [Britain] they were regarded as an unknown quantity, but it was not anticipated that they would give the stronger British teams a great deal of opposition. The result of the very first match against Devon was regarded as a foregone conclusion by most British followers."

- "The anthem in more recent years". BBC Cymru Wales history. BBC Cymru Wales. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- "Centenary of Rugby Football Match 1923". rugbyrelics.com. Retrieved 18 May 2006.

- Bath, p 27

- Girling (1978), p.221

- Schofield, Hugh (8 October 2002). "French rugby league fights for rights". BBC. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Making rugby history". BBC News. 29 January 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- Jimmy Mill at AllBlacks.com

- Harding (2000), pg 31

- Ranji Wilson at AllBlacks.com

- Harding (2000), pg 73

- "'No Maoris – No Tour' poster, 1960". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 10 September 2007. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- Howitt (2005), p.8

- Howitt (2005), p.9

- Howitt (2005), p.12

- Howitt (2005), p.10

- Howitt (2005), p.18

- Howitt (2005), p.15

- Howitt (2005), p.20

- Harlow, Phil (6 December 2006). "Rewriting rugby's laws". BBC. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- http://www.rugbyfootballhistory.com/scoring.htm

- "SANZAR invites Argentina to join the Tri Nations from 2012". 14 September 2009. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "The first international rugby match". BBC. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Reliving victory over the All Blacks 1905-style". BBC. 20 October 2005. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "The History of Wales vs New Zealand". rugbyrelics.com. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "History of the Barbarians". BBC. 21 May 2003. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- Address by Dr. James McDaid, T.D., Minister for Tourism, Sport and Recreation at the launch of the statutory Irish Sports Council, in St Patrick's Hall, Dublin Castle at 2.30p.m. Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 30 June 1999, "He was the inspiration behind the historic Munster victory against the All Blacks in 1978."

- Hodgetts, Rob (7 October 2007). "Deja vu for KO'd Kiwis". BBC.

- "Tale of the Tri-Nations". BBC. 8 July 2002. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

References

- Bath, Richard, ed. (1997). The Complete Book of Rugby. Seven Oaks Ltd. ISBN 1-86200-013-1.

- Bath, Richard, ed. (2007). The Scotland Rugby Miscellany. Vision Sports Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-905326-24-2.

- Collins, Tony (2009). A Social History of English Rugby Union. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-47660-7.

- Rhys, Chris (1984). Cotton, Fran (ed.). The Book of Rugby Disasters & Bizarre Records. London: Century Publishing. ISBN 0-7126-0911-3.

- Howitt, Bob (2005). SANZAR Saga: Ten Years of Super 12 and Tri-Nations Rugby. Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 1-86950-566-2.

- FitzSimmons, Peter (2003). The Rugby War. Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 0-7322-7882-1.

- Girling, D.A., ed. (1978). Everyman's Encyclopedia. 5 (6th ed.). JM Dent & Sons Ltd. ISBN 0-460-04017-0.

- Godwin, Terry; Rhys, Chris (1981). The Guinness Book of Rugby Facts & Feats. Enfield: Guinness Superlatives Ltd. ISBN 0-85112-214-0.

- Griffiths, John (1987). The Phoenix Book of International Rugby Records. London: Phoenix House. ISBN 0-460-07003-7.

- Jones, J.R. (1976). Encyclopedia of Rugby Union Football. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7091-5394-5.

- Richards, Huw (2007). A Game for Hooligans: The History of Rugby Union. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84596-255-5.

- Riordan, James (1977). Sport in Soviet Society – development of sport and physical education in Russia and the USSR. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Starmer-Smith, Nigel, ed. (1986). Rugby – A Way of Life, An Illustrated History of Rugby. Lennard Books. ISBN 0-7126-2662-X.

External links

- A.A. Thomson, "Rugger My Pleasure" Chapter 2: Unhistorical Survey of Rugby

- N Trueman, Rugby Football History

- Scrum V's history of rugby—BBC

- The History of The British & Irish Lions on the website of www.lions-tour.com

- The Development ofknmik Rugby in the River Plate Region