House of the Seven Gables

The House of the Seven Gables (also known as the Turner House or Turner-Ingersoll Mansion) is a 1668 colonial mansion in Salem, Massachusetts, named for its gables. It was made famous by Nathaniel Hawthorne's 1851 novel The House of the Seven Gables. The house is now a non-profit museum, with an admission fee charged for tours, as well as an active settlement house with programs for children. It was built for Captain John Turner and stayed with the family for three generations.[2]

House of the Seven Gables Historic District | |

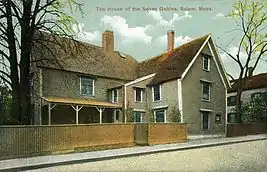

_-_Salem%252C_Massachusetts.jpg.webp) The House of the Seven Gables, Salem, Massachusetts. View of front and side. | |

| |

| Location | Salem, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°31′19″N 70°53′5″W |

| Built | 1668 |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Colonial, Georgian |

| NRHP reference No. | 73000323[1] |

| Added to NRHP | May 8, 1973 |

The house

_-_Salem%252C_Massachusetts.JPG.webp)

The earliest section of the House of the Seven Gables was built in 1668 for Capt. John Turner. It remained in his family for three generations, descending from John Turner II to John Turner III. Facing south towards Salem Harbor, it was originally a two-room, 2 1⁄2-story house with a projecting front porch and a massive central chimney. This portion now forms the middle of the house. Four windows of the original ground-floor room (which became a dining room) remain in the house's side wall.

A few years later, a kitchen lean-to and a new north kitchen ell to the rear of the house were added. By 1676, Turner had added a spacious south (front) extension with its own chimney, containing a parlor on the ground floor, with a large bed chamber above it. Ceilings in this new wing are higher than the very low ceilings in older parts of the house. The new wing featured double casement windows and an overhang with carved pendants; it was capped with a three-gabled garret.

In the first half of the 18th century, John Turner II remodeled the house in the new Georgian style, adding wood paneling and sash windows. These alterations are preserved, very early examples of Georgian decor. The House of the Seven Gables is one of the oldest surviving timber-framed mansion houses in continental North America, with 17 rooms and over 8,000 square feet (700 m2) including its large cellars.

After John Turner III lost the family fortune, the house was acquired by the Ingersolls, who remodeled it again. Gables were removed, porches replaced, and Georgian trim added.

Inspiration for Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne, a relative of the Ingersolls, was infamous for being reclusive during his time living in Salem, in part because Hawthorne himself exaggerated his reputation. He occasionally played whist, for example, with his sister Louisa, his second cousin Susannah Ingersoll, and Ingersoll's adopted son Horace Connolly.[3] Hawthorne was occasionally entertained in the house by Susannah but, by Hawthorne's time, the house had only three gables after a renovation to match more current architectural trends.[4] His cousin told him the house's history, and showed him beams and mortises in the attic indicating locations of former gables. Hawthorne was more inspired by the way "seven gables" sounded than what the house looked like. As he wrote in a letter, "The expression was new and struck me forcibly... I think I shall make something of it."[5] The idea inspired Hawthorne's novel The House of the Seven Gables.

Hawthorne wrote of the house as if it were a living thing. It is described as such in the novel: "The aspect of the venerable mansion has always affected me like a human countenance... It was itself like a great human heart, with a life of its own, and full of rich and sombre reminisces. The deep projection of the section story gave the house a meditative look, that you could not pass it without the idea that it had secret to keep."[6] In writing the book, Hawthorne compared the process to constructing an actual house. In January 1851, he wrote to his publisher James T. Fields that the book was nearly finished, "only I am hammering away a little on the roof, and doing a few odd jobs that were left incomplete."[7] He sent the finished manuscript to Fields by the end of the month.[8] The House of the Seven Gables was published in April 1851.[9]

Horace Ingersoll, Susanna's adopted son, told Hawthorne a story of Acadian lovers that later inspired Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1847 poem Evangeline.

Museum

.jpg.webp)

In 1908, the house was purchased by Caroline O. Emmerton, founder of the House of Seven Gables Settlement Association, and she restored it from 1908 to 1910 as a museum whose admission fees would support the association. Boston architect Joseph Everett Chandler supervised the restoration, which among other alterations reconstructed missing gables. In some cases historical authenticity was sacrificed in the interest of appealing to visitors, who expected the house to match the one Hawthorne described in his romantic novel. Thus, for example, Emmerton added a "cent-shop" resembling that operated by the author's fictional character Hepzibah Pyncheon.[10] A representation of "Maule's Well" was added to the garden.[11]

She also added what looks like a wood closet but has a false back. When opened, the back leads to a secret staircase which leads up to the attic.

Many interesting features of the original mansion remain, including unusual forms of wall insulation, original beams and rafters, and extensive Georgian paneling.

The Nathaniel Hawthorne Birthplace is now immediately adjacent to the House of the Seven Gables, and access to it is granted with the regular admission fee. Although it is indeed the house in which Hawthorne was born and lived to the age of four, the house was sited a few blocks away on Union Street when he inhabited it.

In 1994, the Seamans Visitor Center was opened at the historic site. The visitor center was named in honor of the Seamans family; Donald C. Seamans was responsible for the building project when he was president of the House of the Seven Gables Settlement Association.[12]

On March 29, 2007, the House of the Seven Gables Historic District was designated a National Historic Landmark District.[13]

See also

- List of historic houses in Massachusetts

- List of the oldest buildings in Massachusetts

- List of the oldest buildings in the United States

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Massachusetts

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Salem, Massachusetts

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Essex County, Massachusetts

References

Notes

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- "House of Seven Gables Historic District". NPS.gov. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- Miller, Edwin Haviland. Salem is My Dwelling Place: A Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991: 87. ISBN 0-87745-332-2

- Schmidt, Shannon McKenna and Joni Rendon. Novel Destinations: Literary Landmarks from Jane Austen's Bath to Ernest Heminway's Key West. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2008: 296. ISBN 978-1-4262-0277-3

- Schmidt, Shannon McKenna and Joni Rendon. Novel Destinations: Literary Landmarks from Jane Austen's Bath to Ernest Heminway's Key West. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2008: 297. ISBN 978-1-4262-0277-3

- Schmidt, Shannon McKenna and Joni Rendon. Novel Destinations: Literary Landmarks from Jane Austen's Bath to Ernest Heminway's Key West. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2008: 293. ISBN 978-1-4262-0277-3

- Mellow, James R. Nathaniel Hawthorne in His Times. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1980: 353. ISBN 0-395-27602-0

- Wineapple, Brenda. Hawthorne: A Life. New York: Random House, 2004: 257. ISBN 0-8129-7291-0

- Wineapple, Brenda. Hawthorne: A Life. New York: Random House, 2004: 238. ISBN 0-8129-7291-0

- North Shore Community College. "Hawthorne in Salem: Images Related to the Turner-Ingersoll House, aka "The House of the Seven Gables"". Retrieved 2006-05-31.

- Schmidt, Shannon McKenna and Joni Rendon. Novel Destinations: Literary Landmarks from Jane Austen's Bath to Ernest Heminway's Key West. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2008: 297. ISBN 978-1-4262-0277-3

- Killeen, Wendy (1994-10-16). "Night & Day". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- "National Register of Historic Places Listings: April 13, 2007". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

Further reading

- Goodwin, Lorinda B. R. "Salem's House of Seven Gables as Historic Site." In Salem: Place, Myth, and Memory, edited by Dane Anthony Morrison and Nancy Lusignan Schultz. UPNE, 2005.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to House of the Seven Gables. |

- House of the Seven Gables, official site

- Listing and photographs at the Historic American Buildings Survey

- Official audio tour of the House of the Seven Gables by UniGuide at SoundCloud

- House of the Seven Gables at Destination Salem

- House of the Seven Gables at Atlas Obscura