Human presence in space

Human or anthropogenic presence in space (also humanity in space) is the physical presence of human activity in outer space, and in a broader sense includes the presence at any extraterrestrial astronomical body.

Humans have been present in space either, in the common sense, through their direct activity like human spaceflight, or through mediation of their activity like with uncrewed spaceflight and "telepresence".[1] Human presence in space particularly through mediation can take many physical forms from space debris, uncrewed spacecraft, artificial satellites, space observatories, crewed spacecraft, art in space, to human outposts in outer space such as space stations. While human presence in space, particularly its continuation and permanence can be a goal in itself,[1] human presence can have a range of purposes[2] and modes from space exploration, commercial use of space to space settlement or even colonization and militarisation of space. Human presence in space is realized and sustained through the advancement and application of space sciences, particularly astronautics in the form of spaceflight and space infrastructure.

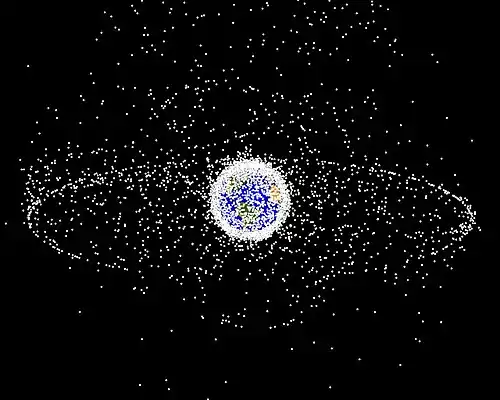

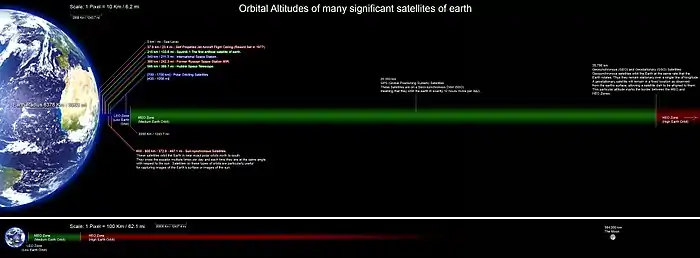

Humans have achieved some mediated presence throughout the Solar System, but the most extensive presence has been in orbit around Earth. Humans have sustained direct presence in orbit around Earth since the year 2000 through continuously crewing the ISS, and with few interruptions through crewing the space station Mir since the later 1980s.[3] The increasing and extensive human presence in orbital space around Earth, beside its benefits, has also produced a threat to it by carrying with it space debris, potentially cascading into the so-called Kessler syndrome.[4] This has raised the need for regulation and mitigation of such to secure a sustainable access to outer space.

Securing the access to space and human presence in space has been pursued and allowed by the establishment of space law and space industry, creating a space infrastructure. But sustainability has remained a challenging goal, with the United Nations seeing the need to advance long-term sustainability of outer space activities in space science and application,[5] and the United States having it as a crucial goal of its contemporary space policy and space program.[6][7]

Terminology

The United States has been using the term "human presence" to identify one of the long term goals of its space program and its international cooperation. While it traditionally means and is used to name direct human presence, it is also used for mediated presence.[1] Differentiating human presence in space between direct and mediated human presence, meaning human or non-human presence, such as with crewed or uncrewed spacecraft, is rooted in a history of how human presence is to be understood (see dedicated chapter).

Human, particularly direct, presence in space is sometimes referred to with "boots on the ground"[1] or equated with space colonization. But the term colonization and even settlement has been questioned to describe human presence in space, since they employ very particular concepts of appropriation, with historic baggage,[8][9][10] addressing the forms of human presence in a particular and not general way.

Alternatively some have used the term "humanization of space",[11][12][13] which differs in focusing on the general development, impact and structure of human presence in space.

On an international level the United Nations uses the phrase of "outer space activity" for the activity of its member states in space.[5]

History

Human presence in space began with the first launches of artificial objects into outer space in the mid 20th century.

Since then the activity and presence in outer space has increased to the point where Earth is orbited by a vast number of artificial objects and the far reaches of the Solar System have been visited and explored by a range of space probes. Human presence throughout the Solar System is continued by different contemporary and future missions, most of them mediating human presence through robotic spaceflight.

First a realized project of the Soviet Union and followed in competition by the United States, human presence in space is now an increasingly international and commercial field.

Representation and participation

Participation and representation of humanity in space is an issue of human access to and presence in space ever since the beginning of spaceflight.[14] Different space agencies, space programs and interest groups such as the International Astronomical Union have been formed supporting or producing humanity's or a particular human presence in space. Representation has been shaped by the inclusiveness, scope and varying capabilities of these organizations and programs.

Some rights of non-spacefaring countries to partake in spaceflight have been secured through international space law, declaring space the "province of all mankind", understanding spaceflight as its resource, though sharing of space for all humanity is still criticized as imperialist and lacking.[14]

Additionally to international inclusion the inclusion of women[15] and people of colour has also been lacking. To reach a more inclusive spaceflight some organizations like the Justspace Alliance[14] and IAU featured Inclusive Astronomy[16] have been formed in recent years.

Law and governance

Space activity is legally based on the Outer Space Treaty, the main international treaty. Though there are other international agreements such as the significantly less ratified Moon Treaty.

The Outer Space Treaty established the basic ramifications for space activity in article one: "The exploration and use of outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all mankind."

And continued in article two by stating: "Outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means."[17]

The development of international space law has revolved much around outer space being defined as common heritage of mankind. The Magna Carta of Space presented by William A. Hyman in 1966 framed outer space explicitly not as terra nullius but as res communis, which subsequently influenced the work of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS).[14][18]

Forms of human presence

Signals and radiation

Humans have been sending unintentionally and intentionally signals into space since stronger radio technology has been used in the 20th century, well before any physical human presence in space. Traveling at light speed these relatively faint signals have reached distant star systems as far away as the age of the signals.[19]

The extensive activity of humans on Earth and beyond has produced a range of radiation traveling into and from space, causing particularly issues for human activity in the form of radio spectrum pollution and light pollution.

Space junk and human impact

Space junk as product and form of human presence in space has existed ever since the first spaceflights and comes mostly in the form of space debris in outer space. Space debris has been for example possibly the first human objects to have been present in space beyond Earth, reaching its escape velocity after being launched by an Aerobee rocket in 1957.[20] Most space debris is in orbit around Earth, it can stay there for years to centuries if at altitudes from hundrets to thousands of kilometers, before it falls to Earth.[21] Space debris is a hazard since it can hit and damage spacecraft. Having reached considerable amounts around Earth, policies have been put into place to prevent space debris.

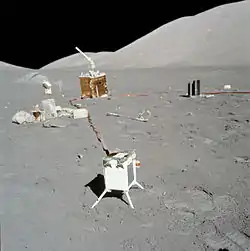

But space junk can also come as result of human activity on astronomical bodies, such as the remains of space missions, like the many artificial objects left behind on the Moon.[22]

Robotic

Human presence in space has been strongly based on the many robotic spacecraft, particularly as the many artificial satellites in orbit around Earth.

Many firsts of human presence in space have been achieved by robotic missions. The first sustained presence in space was established by Sputnik in 1958. Followed by a rich number of robotic space probes achieving human presence and exploration throughout the Solar system for the first time.

Human presence at the Moon was established by the Luna programme, with an impactor in 1959 (Luna 2), a lander (Luna 9) as well as an orbiter in 1966 (Luna 10) and in 1970 with the first rover (Lunokhod 1) on an extraterrestrial body.

Interplanetary presence was established at Venus by the Venera program, with a flyby in 1961 (Venera 1) and a crash in 1966 (Venera 3).[23][24]

Presence in the outer Solar System was achieved by Pioneer 10 in 1972[25] and continuous presence in interstellar space by Voyager 1 in 2012.[26]

The 1958 Vanguard 1 is the fourth artificial satellite and the oldest spacecraft still in space and orbit around Earth, though inactive.[27]

Presence of non-human life from Earth

As participants of human outer space activities non-human animals, plants[29] and microorganisms have been present as subjects of research in space, particularly bioastronautics and astrobiology, being closely monitored and used for diverse tests. The first animals (including humans) in space were fruit flies and mammals like the Albert monkeys and the dog Laika in the 1940s and 1950s, becoming also the first fatalities of animals (including humans) of spaceflight and in space.

Microorganisms have also been present in space since the very beginning of spaceflight. They have been the subject of planetary protection, because of the problem of interplanetary contamination, and are used and studied as subjects in space research.

Direct human presence in space

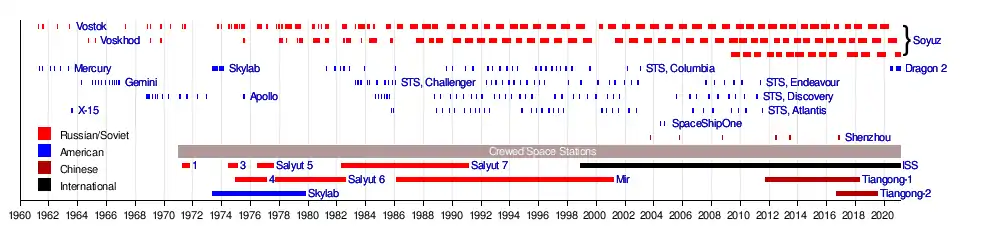

Direct human presence in space was achieved with Yuri Gagarin flying a space capsule in 1961 for one orbit around Earth for the first time. With Alexei Leonov in 1965 the first human went out of a spacecraft into open space in an extravehicular activity.

Though Valentina Tereshkova was in 1963 the first woman in space, women saw no further presence in space until the 1980s and are still underrepresented, e.g. with no women ever being present on the Moon.[15] A diversification of direct human presence in space started with the first meeting of two crews of the Apollo–Soyuz mission in 1975 and at the end of the 1970s with the Interkosmos program.

Space stations have harboured so far the only long-duration direct human presence in space, starting with Salyut 1 in 1971. Since the 1980s an almost continuous direct human presence in space has been achieved with the operation of the stations Mir and its successor the ISS.[3] At times the number of people present in space at the same time has climbed up to 13 people.[30]

Non-governmental persons have been present in space as spaceflight participants since 2001.

Beyond Earth the Moon has been the only astronomical object which so far has seen direct human presence through the short-term Apollo missions between 1968 and 1972, beginning with the first orbit by Apollo 8 in 1968 and with the first landing by Apollo 11 in 1969.

By the end of the 2010s several hundred people from more than 40 countries have gone into space, most of them reaching orbit. 24 people have traveled beyond low Earth orbit and 12 of them walked on the Moon.[31] Space travelers have spent over 29,000 person-days (or a cumulative total of over 77 years) in space including over 100 person-days of spacewalks.[32]

Space infrastructure

A permanent human presence in space depends on an established space infrastructure which harbours, supplies and maintains human presence. Such infrastructure has originally been Earth ground-based, but with increased numbers of satellites and long-duration missions beyond the near side of the moon space-to-space based infrastructure is being used. First simple interplanetary infrastructures have been created by space probes particularly when employing a system which combines a lander and a relaying orbiter.

Space stations as space habitats have provided a crucial infrastructure for sustaining a continuous direct human, including non-human, presence in space. Space stations have been continuously present in orbit around Earth from Skylab in 1973, to the Salyut stations, Mir and eventually ISS. The planned Artemis program includes the Lunar Gateway a future space station around the Moon as a multimission waystation.[33]

Artistic

Human presence has also been expressed artistically through permanent installations on celestial bodies like on the Moon.

Religion

Presence of religion in space has been realized through people like Apollo 15 Mission Commander David Scott who left a Bible on their lunar rover during an extravehicular activity on the Moon, or with people on the ISS celebrating Christmas.

Human presence at extraterrestrial bodies

Humanity has reached different types of astronomical bodies, but the longest and most diverse presence (including non-human, e.g. sprouting plants[29]) has been on the Moon, particularly because it is the first and only extraterrestrial body having been directly visited by humans.

Space probes have been mediating human presence on other astronomical bodies since their first visits to Venus. Mars has seen a continuous presence since 1997,[34] after being first flown by in 1964 and landed on in 1971. A group of missions have been present on Mars since 2001, including continuous presence by a series of rovers since 2003.

Beside having reached some planetary-mass objects (that is planets, dwarf planets or the largest, so-called planetary-mass moons), humans have also reached, landed and in some cases even returned from some small Solar System bodies, like asteroids and comets, with a range of space probes.

Future direct human presence is planned with crewed research stations on Mars and the Moon, e.g. through the Artemis program, which have been in development, but have yet to be established.

.jpg.webp)

Human presence at particular orbits

Humans have been present beyond high planetary orbits soon after the first spaceflight.[20]

Human presence in interplanetary orbits or heliocentric orbit has been the case with a range of artificial objects since the beginning of spaceflight.[20]

Humans have also used and occupied co-orbital configurations, particularly at different liberation points with halo orbits, to harness the benefits of those so called Lagrange points.

Human presence in the outer Solar System

Human presence in the outer Solar System has been established and continued by mediating space probes since the first visit to Jupiter in 1973 by Pioneer 10.[25]

The Saturn moon Titan, with its special lunar atmosphere, has so far been the only body in the outer Solar system to be landed on by the Cassini–Huygens lander Huygens in 2005.

Outbound

Several probes have reached Solar escape velocity, with Voyager 1 being the first to cross after 36 years of flight the heliopause and enter interstellar space on August 25, 2012 at distance of 121 AU from the Sun.[26]

Living in space

Space, particularly microgravity, make life different to life on Earth. Mundane needs such as air, pressure, temperature and light, as well as movement, hygiene and food intake are confronted with challenges.

Human health is mostly effected by long-duration stays particularly by the prevalent radiation exposure and the health effects of microgravity. Human fatalities have been the case due to accidents during spaceflight, particularly at launch and reentry. With the last in-flight accident killing humans, the Columbia accident in 2003, the sum of in-flight fatalities has risen to 15 astronauts and 4 cosmonauts, in five separate incidents.[36][37] Over 100 others have died in accidents during activity directly related to spaceflight or testing.

People have worked in bioastronautics, space medicine, space technology and space architecture which address and work on alleviating the effects of space on humans and non-humans.

Impact of human presence: environmental protection and sustainability

Human space activity, and its subsequent presence, can and has been having an impact on space as well as on the capacity to access it. This impact of human space activity and presence, or its potential, has caused the need to address its issues from planetary protection, space debris, radio pollution and light pollution, to the reusability of launch systems.

Sustainability has been a goal of space law, space technology and space infrastructure, with the United Nations seeing the need to advance long-term sustainability of outer space activities in space science and application,[5] and the United States having it as a crucial goal of its contemporary space policy and space program.[6][7]

Human presence in space is particularly being felt in orbit around Earth. The orbital space around Earth has seen increasing and extensive human presence, beside its benefits it has also produced a threat to it by carrying with it space debris, potentially cascading into the so-called Kessler syndrome.[4] This has raised the need for regulation and mitigation of such to secure a sustainable access to outer space.

Study of and reflections on space and presence

Individually or as a society humans have engaged since pre-history in developing their perception of space above the ground, or the cosmos at large, and developing their place in it.

Social sciences have been studying such works of people from pre-history to the contemporary with the fields of archaeoastronomy to cultural astronomy. With actual human activity and presence in space the need for fields like astrosociology and space archaeology have been added.

Human presence observed from space

Earth observation has been one of the first missions of spaceflight, resulting in a dense contemporary presence of Earth observation satellites, having a wealth of uses and benefits for life on Earth.

Viewing human presence from space, particularly by humans directly, has been reported by some astronauts to cause a cognitive shift in perception, especially while viewing the Earth from outer space, this effect has been called the overview effect.

Observation of space from space

Parallel to the above overview effect the term "ultraview effect" has been introduced for a subjective response of intense awe some astronauts have experienced viewing large "starfields" while in space.[38]

Space observatories like the Hubble Space Telescope have been present in Earth's orbit, benefiting from advantages from being outside Earth's atmosphere and away from its radio noise, resulting in less distorted observation results.

Location in space

The location of human presence has been studied throughout history by astronomy and was significant in order to relate to the heavens, that is to space and its bodies.

The historic argument between geocentrism and heliocentrism is one example about the location of human presence.

Scenarios of and relations to space beyond human presence

Realizations of the scales of space, have been taken as subject to discuss human and life's existence or relations to space and time beyond them, with some understanding humanity's or life's presence as a singularity or one to be in isolation, pondering on the Fermi paradox.

A diverse range of arguments of how to relate to space beyond human presence have been raised, with some seeing space beyond humans as reason to venture out into space and exploringt it, some aiming for contact with extraterrestrial life, to arguments for protection of humanity or life from its possibilities.[39][40]

Direct and mediated human presence

Related to the long discussion of what human presence constitutes and how it should be lived, the discussion about direct (e.g. crewed) and mediated (e.g. uncrewed) human presence, has been decisive for how space policy makers have chosen human presence and its purposes.[41]

The relevance of this issue for space policy has risen with the advancement and resulting possibilities of telerobotics,[1] to the point where most of the human presence in space has been reallized robotically, leaving direct human presence behind.

Purposes and uses

Space and human presence in it has been the subject of different agendas.

Human presence in space at its beginnings, was marked by the Cold War and its outgrowing the Space Race. During this time technological, nationalist, ideological and military competition were dominant driving factors of space policy[42] and the resulting activity and, particularly direct human, presence in space.

With the waning of the Space Race, concluded by cooperation in human spaceflight, focus shifted in the 1970s further to space exploration and telerobotics, fueled by its rich achievements and technological advances.[43] Space exploration meant by then also an engagement by governments in the search for extraterrestrial life.

Since human activity and presence in space has been producing benefits beyond the above purposes as spin-off and for civilian use such as Earth communication satellites, international cooperation to advance these grew with time.[44] The United Nations has been set to safeguard human activity in outer space in a sustainable way, for the purpose of continuing the benefits of space infrastructure and space science.[5]

With the contemporary so-called NewSpace, the aim of commercialization of space has grown, as well as a public narrative of space habitation for the survival of some humans without Earth, which has been criticized as space colonialism.[45]

Overview of different purposes and uses

- Space research

- Communication

- Spaceflight/Space transportation

- Commercial use of space

- For presence, in it self (see Human outpost basing)

- Space habitation

- Emigration from Earth

- Integration

- Demographic push (e.g. due to overconsumption)

- Forced displacement

- Space and survival

- Escapism

- Space colonization (see also Settler colonialism, Exceptionalism and Utopianism)

- Emigration from Earth

- Space development as a purpose (see also New Frontier and Progress)

- Expansionism (see also Manifest destiny)

- Terraforming

- Panspermia

- Planetary protection

- National or private potency and competition (see Space Race)

- Militarization of space

See also

- Interplanetary contamination

- Extremophile

- Outline of space science

- Outline of space exploration

- Timeline of Solar System exploration

- List of spaceflight records

- Astrobiology

- Extraterrestrial life

- Human impact on the environment

- Human ecology

- Technosignature

- World Ocean § Anthropogenic presence and impact

References

- Dan Lester (November 2013). "Achieving Human Presence in Space Exploration". Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments. MIT Press. 22 (4): 345–349. doi:10.1162/PRES_a_00160. S2CID 41221956.

- Barbara Imhof; Maria João Durãmo; Theodore Hall (December 2017). "Next steps in sustaining human presence in space". Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Rebecca Boyle (2 November 2010). "The International Space Station Has Been Continuously Inhabited for Ten Years Today". Popular Science. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- William Poor (19 January 2021). "Outer space is a mess that Moriba Jah wants to clean up". Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- "Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities". United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- "2020 COPUOS STSC – U.S on Long-Term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities". 3 February 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- Jennifer A. Manner (22 December 2020). "Building on the Artemis Accords to address space sustainability". Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- Mike Wall (25 October 2019). "Bill Nye: It's Space Settlement, Not Colonization". Space.com. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- DNLee (26 March 2015). "When discussing Humanity's next move to space, the language we use matters". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Drake, Nadia (2018-11-09). "We need to change the way we talk about space exploration". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2019-10-16. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- Peter Dickens; James Ormrod (2016). "Introduction: the production of outer space". In James Ormrod; Peter Dickens (eds.). The Palgrave handbook of society, culture and outer space. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–43. ISBN 9781137363510.

- Arcynta Ali Childs (2011-06-11). "Q & A: Nichelle Nichols, AKA Lt. Uhura, and NASA". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

Ten years after "Star Trek" was cancelled, almost to the day, I was invited to join the board of directors of the newly formed National Space Society. They flew me to Washington and I gave a speech called “New Opportunities for the Humanization of Space” or “Space, What's in it for me?” In [the speech], I'm going where no man or woman dares go. I took NASA on for not including women and I gave some history of the powerful women who had applied and, after five times applying, felt disenfranchised and backed off. [At that time] NASA was having their fifth or sixth recruitment and women and ethnic people [were] staying away in droves. I was asked to come to headquarters the next day and they wanted me to assist them in persuading women and people of ethnic backgrounds that NASA was serious [about recruiting them]. And I said you’ve got to be joking; I didn't take them seriously. . . . John Yardley, who I knew from working on a previous project, was in the room and said 'Nichelle, we are serious.' I said OK. I will do this and I will bring you the most qualified people on the planet, as qualified as anyone you’ve ever had and I will bring them in droves. And if you do not pick a person of color, if you do not pick a woman, if it's the same old, same old, all-white male astronaut corps, that you’ve done for the last five years, and I'm just another dupe, I will be your worst nightmare.

- Dickens, Peter; Ormrod, James (Nov 2010). The Humanization of the Cosmos - to What End?. Monthly Review. Archived from the original on 2016-10-03. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- Haris Durrani (19 July 2019). "Is Spaceflight Colonialism?". Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Alice Gorman (16 June 2020). "Almost 90% of astronauts have been men. But the future of space may be female". Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Website of the IAU100 Inclusive Astronomy project

- "Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Alexander Lock (6 June 2015). "Space: The Final Frontier". The British Library – Medieval manuscripts blog. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Emily Lakdawalla (24 February 2012). "This is how far human radio broadcasts have reached into the galaxy". Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- Maurer, S.M. (2001), "Idea Man" (PDF), Beamline, 31 (1), retrieved 2020-11-20

- "Frequently Asked Questions: Orbital Debris". NASA. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- Jonathan O'Callaghan. "What is space junk and why is it a problem?". Natural History Museum, London. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Siddiqi, Asif A. (2018). Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration, 1958–2016 (PDF). The NASA history series (second ed.). Washington, DC: NASA History Program Office. p. 1. ISBN 9781626830424. LCCN 2017059404. SP2018-4041.

- "Venera 3". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive.

- Chris Gebhardt (15 July 2017). "Pioneer 10: first probe to leave the inner solar system & precursor to Juno". Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Morin, Monte (September 12, 2013). "NASA confirms Voyager 1 has left the Solar System". Los Angeles Times.

- "Vanguard 1, Oldest Manmade Satellite, Turns 60 This Weekend". AmericaSpace. Ben Evans. March 18, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- Isachenkov, Vladimir (11 April 2008), "Russia opens monument to space dog Laika", Associated Press, archived from the original on 26 September 2015, retrieved 30 August 2020

- Zheng, William (15 January 2019). "Chinese lunar lander's cotton seeds spring to life on far side of the moon". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Tariq Malik (27 March 2009). "Population in Space at Historic High: 13". Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "Astronaut/Cosmonaut Statistics". www.worldspaceflight.com. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. Retrieved 2007-02-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Greg Autry (22 August 2019). "NASA must shift its focus to infrastructure and capabilities that support dynamic missions". SpaceNews. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- Clark, Stephen (4 July 2017). "NASA marks 20 years of continuous Mars exploration". Spaceflightnow. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- Jackson, Shanessa (11 September 2018). "Competition Seeks University Concepts for Gateway and Deep Space Exploration Capabilities". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Harwood (2005).

- Musgrave, Larsen, Tommaso (2009), p. 143.

- Weibel, Deana (13 August 2020). "The Overview Effect and the Ultraview Effect: How Extreme Experiences in/of Outer Space Influence Religious Beliefs in Astronauts". Religions. 11 (8): 418. doi:10.3390/rel11080418. S2CID 225477388.

- Michael Greshko (2 May 2018). "Stephen Hawking's Most Provocative Moments, From Evil Aliens to Black Hole Wagers". National Geographic. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- Joel Achenbach (1 March 2015). "Searching for life beyond Earth: Scientists debate danger of messages to 'hostile' aliens". The Independent. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- Alex Ellery (1999). "A robotics perspective on humdn spaceflight". Earth, Moon, and Planets. Kluwer Academic Publishers. 87 (3): 173–190. doi:10.1023/A:1013190908003. S2CID 116182207. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- "Space Race". National Cold War Exhibition. Royal Air Force Museum. 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- Launiusa, Roger; McCurdyb, Howard (2007). "Robots and humans in space flight: Technology, evolution, and interplanetary travel". Technology in Society. Elsevier Ltd. 29 (3): 271–282. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2007.04.007.

- Gurtuna, Ozgur (2013). Fundamentals of Space Business and Economics. SpringerBriefs in Space Development. Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London: Springer. p. 31. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6696-3. ISBN 978-1-4614-6695-6.

- Joon Yun (January 2, 2020). "The Problem With Today's Ideas About Space Exploration". Worth.com. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

.jpg.webp)