STS-107

STS-107 was the disastrous 113th flight of the Space Shuttle program, and the 28th and final flight of Space Shuttle Columbia. The mission launched from Kennedy Space Center in Florida on 16 January 2003 and during its 15 days, 22 hours, 20 minutes, 32 seconds in orbit conducted a multitude of international scientific experiments.[1]

Spacehab's Research Double Module in Columbia's payload bay during STS-107 | |

| Mission type | Microgravity research |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 2003-003A |

| SATCAT no. | 27647 |

| Mission duration | 15 days, 22 hours, 20 minutes, 32 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 6,600,000 miles (10,600,000 km) |

| Orbits completed | 255 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Columbia |

| Launch mass | 263,706 pounds (119,615 kg) |

| Landing mass | 232,793 pounds (105,593 kg) (expected) |

| Payload mass | 32,084 pounds (14,553 kg) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 7 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 16 January 2003 15:39:00 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Decay date | 1 February 2003, 13:59:32 UTC Disintegrated during reentry |

| Landing site | Kennedy SLF Runway 33 (planned) |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 170 miles (270 km) |

| Apogee altitude | 177 miles (285 km) |

| Inclination | 39.0 degrees |

| Period | 90.1 minutes |

Rear (L-R): David Brown, Laurel Clark, Michael Anderson, Ilan Ramon; Front (L-R): Rick Husband, Kalpana Chawla, William McCool | |

An in-flight break up during reentry into the atmosphere on 1 February killed all seven crew members and disintegrated Columbia. Immediately after the disaster, NASA convened the Columbia Accident Investigation Board to determine the cause of the disintegration. The source of the failure was determined to have been caused by a piece of foam that broke off during launch and damaged the thermal protection system (reinforced carbon-carbon panels and thermal protection tiles) on the leading edge of the orbiter's left wing. During re-entry the damaged wing slowly overheated and came apart, eventually leading to loss of control and disintegration of the vehicle. The cockpit window frame is now exhibited in a memorial inside the Space Shuttle Atlantis Pavilion at the Kennedy Space Center.

The damage to the thermal protection system on the wing was similar to that Atlantis had sustained back in 1988 during STS-27, the second mission after the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. However, the damage on STS-27 occurred at a spot that had more robust metal (a thin steel plate near the landing gear), and that mission survived the re-entry.

Mission highlights

STS-107 carried the SPACEHAB Double Research Module on its inaugural flight, the Freestar experiment (mounted on a Hitchhiker Program rack), and the Extended Duration Orbiter pallet. SPACEHAB was first flown on STS-57.

One of the experiments, a video taken to study atmospheric dust, may have detected a new atmospheric phenomenon, dubbed a "TIGER" (Transient Ionospheric Glow Emission in Red).[2]

On board Columbia was a copy of a drawing by Petr Ginz, the editor-in-chief of the magazine Vedem, who depicted what he imagined the Earth looked like from the Moon when he was a 14-year-old prisoner in the Terezín concentration camp. The copy was in the possession of Ilan Ramon and was lost in the disintegration. Ramon also traveled with a dollar bill received from the Lubavitcher Rebbe.[3]

An Australian experiment, conducted by students from Glen Waverley Secondary College, was designed to test the reaction of zero gravity on the web formation of the Garden Orb Spider.[4]

Major experiments

Examples of some of the experiments and investigations on the mission.[5]

In SPACEHAB RDM:[5]

- 9 commercial payloads with 21 investigations,

- 4 payloads for the European Space Agency with 14 investigations

- 1 payload for ISS Risk Mitigation

- 18 payloads NASA's Office of Biological and Physical Research (OBPR) with 23 investigations

In the payload bay attached to RDM:[5]

- Combined Two-Phase Loop Experiment (COM2PLEX),

- Miniature Satellite Threat Reporting System (MSTRS)

- Star Navigation (STARNAV).

- Critical Viscosity of Xenon- 2 (CVX-2)

- Low Power Transceiver (LPT)

- Mediterranean Israeli Dust Experiment (MEIDEX)

- Space Experiment Module (SEM- 14)

- Solar Constant Experiment-3 (SOLCON-3)

- Shuttle Ozone Limb Sounding Experiment (SOLSE-2)

Additional payloads[5]

- Shuttle Ionospheric Modification with Pulsed Local Exhaust Experiment (SIMPLEX)

- Ram Burn Observation (RAMBO).

Because much of the data was transmitted during the mission, there was still large return on the mission objectives even though it was lost on re-entry. NASA estimated that 30% of the total science data was saved and collected through telemetry back to ground stations. Around 5-10% more data was saved and collected through recovering samples and hard drives intact on the ground after the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster, increasing the total data of saved experiments despite the disaster from 30% to 35-40%.[5][6]

About 5-6 Columbia payloads encompassing many experiments were successfully recovered in the debris field. Scientists and engineers were able to recover 99% of the data for one of the six FREESTAR experiments, Critical Viscosity of Xenon-2 (CVX-2), that flew unpressurized in the payload bay during the mission after recovering the viscometer and hard drive damaged but fully intact in the debris field in Texas. NASA recovered a commercial payload, Commercial Instrumentation Technology Associates (ITA) Biomedical Experiments-2 (CIBX-2), and ITA was able to increase the total data saved from STS-107 from 0% to 50% for this payload. This experiment studied treatments for cancer, and the micro-encapsulation experiment part of the payload was completely recovered, increasing from 0% data to 90% data after recovering the samples fully intact for this experiment. In this same payload were numerous crystal-forming experiments by hundreds of elementary and middle school students from all across the United States. Miraculously most of their experiments were found intact in CIBX-2, increasing from 0% data to 100% fully recovered data. The BRIC-14 (moss growth experiment) and BRIC-60 (Caenorhabditis elegans ringworm experiment) samples were found intact in the debris field within a 12 mile radius in east Texas. 80-87% of these live organisms survived the catastrophe. The moss and ringworms experiments' original primary mission was not nominal due to the lack of having the samples immediately after landing in its original state (they were discovered many months after the crash), but these samples helped the scientific community greatly in the field of astrobiology and helped form new theories about microorganisms surviving a long trip in outer space while traveling on meteorites or asteroids.[7]

Unsuccessful re-entry

KSC landing was planned for Feb. 1 after a 16-day mission, but Columbia and crew were lost during re-entry over East Texas at about 9 a.m. EST, 16 minutes prior to the scheduled touchdown at KSC.

— NASA [5]

Columbia began re-entry as planned, but the heat shield was compromised due to damage sustained during the initial ascent. The heat of re-entry was free to spread into the damaged portion of the orbiter, ultimately causing its disintegration and the loss of all hands.

The accident triggered a 7-month investigation and a search for debris, and over 85,000 pieces were collected over the course of the initial investigation.[5] This amounted to roughly 38 percent of the orbiter vehicle.[5]

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Second and last spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Only spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Only spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | Second and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Second and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 4 | Only spaceflight | |

| Payload Specialist 1 | Only spaceflight | |

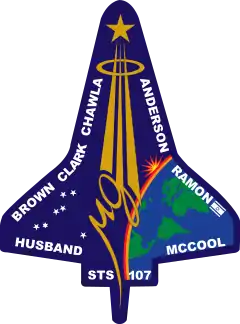

Insignia

The mission insignia itself is the only patch of the shuttle program that is entirely shaped in the orbiter's outline. The central element of the patch is the microgravity symbol, µg, flowing into the rays of the astronaut symbol.

The mission inclination is portrayed by the 39-degree angle of the astronaut symbol to the Earth's horizon. The sunrise is representative of the numerous experiments that are the dawn of a new era for continued microgravity research on the International Space Station and beyond. The breadth of science and the exploration of space is illustrated by the Earth and stars. The constellation Columba (the dove) was chosen to symbolize peace on Earth and the Space Shuttle Columbia. The seven stars also represent the mission crew members and honor the original astronauts who paved the way to make research in space possible. Six stars have five points, the seventh has six points like a Star of David, symbolizing the Israeli Space Agency's contributions to the mission.

An Israeli flag is adjacent to the name of Payload Specialist Ramon, who was the first Israeli in space. The crew insignia or 'patch' design was initiated by crew members Dr. Laurel Clark and Dr. Kalpana Chawla.[8] First-time crew member Clark provided most of the design concepts as Chawla led the design of her maiden voyage STS-87 insignia. Clark also pointed out that the dove in the Columba constellation was mythologically connected to the explorers the Argonauts who released the dove.[9]

Gallery

Launch of STS-107 from Launch Pad 39A at Kennedy Space Center.

Launch of STS-107 from Launch Pad 39A at Kennedy Space Center. Mission STS-107 crew in bunk beds on the middeck of the Space Shuttle.

Mission STS-107 crew in bunk beds on the middeck of the Space Shuttle. Reentry video frame.

Reentry video frame. View of the atmosphere and of the Moon.

View of the atmosphere and of the Moon..jpg.webp) A view of Mount Fuji and the surrounding area from Columbia

A view of Mount Fuji and the surrounding area from Columbia

References

- "HSF - STS-107 Science". NASA. 30 May 2003. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- "Columbia crew saw new atmospheric phenomenon". Newscientist.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- Brown, Irene (27 January 2003). "Israeli astronaut busy up in space". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Archived from the original on 30 November 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- "Australian space spiders perish". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 February 2003. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- KSC, Lynda Warnock. "NASA - STS-107". www.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- https://spaceflight.nasa.gov/shuttle/archives/sts-107/Science_Gained_05-30-03.pdf . Retrieved 5 December 2020

- https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20040111285/downloads/20040111285.pdf . Retrieved 5 December 2020

- "Space Shuttle – STS-107". Spacepatches.nl. 16 January 2003. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- "Constellation Columba". coldwater.k12.mi.us. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Literature

- William H. Starbuck, Moshe Farjoun (Eds.): Organization at the Limit: Lessons from the Columbia Disaster. Blackwell, Malden 2005, ISBN 140513108X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to STS-107. |

- NASA's Space Shuttle Columbia and Her Crew

- NASA STS-107 Crew Memorial web page

- NASA's STS-107 Space Research Web Site

- Spaceflight Now: STS-107 Mission Report

- Science Reports at the Wayback Machine (archived 23 April 2007)

- Press Kit

- Article describing experiments which survived the disaster

- Article: Astronaut Laurel Clark from Racine, WI

- Status reports Detailed NASA status reports for each day of the mission.

.jpg.webp)