Lunar Gateway

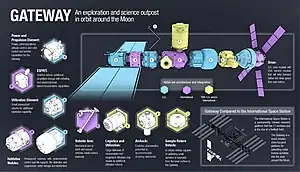

The Lunar Gateway, or simply the Gateway, is a planned small space station in lunar orbit intended to serve as a solar-powered communication hub, science laboratory, short-term habitation module, and holding area for rovers and other robots.[4]

.jpg.webp) Concept art of the Gateway as it is intended to appear in 2024; the PPE and HALO modules are visible with a cargo spacecraft docked. | |

| |

| Station statistics | |

|---|---|

| Crew | 4 (planned) |

| Launch | 2024 (planned) [1] |

| Carrier rocket | SpaceX Falcon Heavy, ULA Vulcan Centaur, and Blue Origin New Glenn |

| Launch pad | Kennedy Space Center |

| Mission status | Modules in development: Power and Propulsion Element HALO |

| Pressurised volume | ≥125 m3 (4,400 cu ft) (planned)[2] |

| Periselene altitude | 3,000 km (1,900 mi)[3] |

| Aposelene altitude | 70,000 km (43,000 mi) |

| Orbital inclination | Polar near-rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO) |

| Orbital period | ≈7 days |

| Configuration | |

Although not the final configuration, this infographic shows the current lineup of parts that will compose the Gateway.

US modules

International modules

TBD: US and/or international modules | |

Formerly known as the Deep Space Gateway (DSG), the station was renamed Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway (LOP-G) in NASA's 2018 proposal for the 2019 United States federal budget.[5][6] When the budgeting process was complete, US$332 million had been committed by Congress to preliminary studies.[7][8][9]

The science disciplines to be studied on the Gateway are expected to include planetary science, astrophysics, Earth observation, heliophysics, fundamental space biology, and human health and performance.[10] Gateway development includes four of the International Space Station partner agencies: NASA, ESA, JAXA, and CSA. Construction is planned to take place in the 2020s.[11][12][13] The International Space Exploration Coordination Group (ISECG), which is composed of more than 14 space agencies including all major ones, has concluded that Gateway will be critical in expanding a human presence to the Moon, Mars, and deeper into the Solar System.[14]

The Gateway is with its name and logo associated with the American frontier symbol of the St. Louis Gateway Arch.[15]

The project is expected to play a major role in NASA's Artemis program, after 2024. While the project is led by NASA, the Gateway is meant to be developed, serviced, and utilized in collaboration with the Canadian Space Agency, European Space Agency, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, and commercial partners. It will serve as the staging point for both robotic and crewed exploration of the lunar south pole, and is the proposed staging point for NASA's Deep Space Transport concept for transport to Mars.[16][11][17]

On 27 September 2017, an informal joint statement on cooperation regarding the program between NASA and Russia's Roscosmos was announced.[13] However, in October 2020 Dmitry Rogozin, director general of Roscosmos, said that the program is too “U.S.-centric” for Roscosmos to participate in.[18] In January 2021 Roscosmos announced that it will not participate in the program.[19]

History

Studies

An earlier NASA proposal for a cislunar station had been made public in 2012 and was dubbed the Deep Space Habitat. That proposal had led to funding in 2015 under the NextSTEP program to study the requirements of deep space habitats.[20] In February 2018, it was announced that the NextSTEP studies and other ISS partner studies would help to guide the capabilities required of the Gateway's habitation modules.[21] The solar electric Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) of the Gateway was originally a part of the now-canceled Asteroid Redirect Mission.[22][23] On 7 November 2017, NASA asked the global science community to submit concepts for scientific studies that could take advantage of the Deep Space Gateway's location in cislunar space.[10] The Deep Space Gateway Concept Science Workshop was held in Denver, Colorado from 27 February to 1 March 2018. This three-day conference was a workshop where 196 presentations were given for possible scientific studies that could be advanced through the use of the Gateway.[24]

In 2018, NASA initiated a Revolutionary Aerospace Systems Concepts Academic Linkage (RASC-AL) competition for universities to develop concepts and capabilities for the Gateway. The competitors are asked to employ original engineering and analysis in one of four areas; "Gateway Uncrewed Utilization and Operations", "Gateway-Based Human Lunar Surface Access", "Gateway Logistics as a Science Platform", and "Design of a Gateway-Based Cislunar Tug". Teams of undergraduate and graduate students were asked to submit a response by 17 January 2019 addressing one of these four themes. NASA will select 20 teams to continue developing proposed concepts. Fourteen of the teams presented their projects in person in June 2019 at the RASC-AL Forum in Cocoa Beach, Florida, receiving a US$6,000 stipend to participate in the Forum.[4]"Lunar Exploration and Access to Polar Regions" from the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez was the winning concept.[25]

Power and propulsion

On 1 November 2017, NASA commissioned 5 studies lasting four months into affordable ways to develop the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE), hopefully leveraging private companies' plans. These studies had a combined budget of US$2.4 million. The companies performing the PPE studies were Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Orbital ATK, Sierra Nevada and Space Systems/Loral.[26][23] These awards are in addition to the ongoing set of NextSTEP-2 awards made in 2016 to study development and make ground prototypes of habitat modules that could be used on the Gateway as well as other commercial applications,[17] so the Gateway is likely to incorporate components developed under NextSTEP as well.[23][27] NASA officials stated that the most likely ion engine to be used on the PPE is the 14 kW Hall thruster called Advanced Electric Propulsion System (AEPS) which has an Isp of up to 2,600 s (25 km/s). The engine is being developed by Glenn Research Center, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and Aerojet Rocketdyne.[28] Four identical AEPS engines would consume the 50 kW generated.[28] In 2019, the contract to manufacture the PPE was awarded to MDA.[29] After a one-year demonstration period, NASA would then "exercise a contract option to take over control of the spacecraft".[30] Its expected service time is about 15 years.[31]

Orbit and operations

The Gateway is planned to be deployed in a highly elliptical seven-day near-rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO) around the Moon, which would bring the station within 3,000 km (1,900 mi) of the lunar north pole at closest approach and as far away as 70,000 km (43,000 mi) over the lunar south pole.[3][32][33] Traveling to and from cislunar space (lunar orbit) is intended to develop the knowledge and experience necessary to venture beyond the Moon and into deep space. The proposed NRHO would allow lunar expeditions from the Gateway to reach a low polar orbit with a delta-v of 730 m/s and a half a day of transit time. Orbital station-keeping would require less than 10 m/s of delta-v per year, and the orbital inclination could be shifted with a relatively small delta-v expenditure, allowing access to most of the lunar surface. Spacecraft launched from Earth would perform a powered flyby of the Moon (delta-v ≈ 180 m/s) followed by a ≈240 m/s delta-v NRHO insertion burn to dock with the Gateway as it approaches the apoapsis point of its orbit. The total travel time would be 5 days; the return to Earth would be similar in terms of trip duration and delta-v requirement if the spacecraft spends 11 days at the Gateway. The crewed mission duration of 21 days and ≈840 m/s delta-v are limited by the capabilities of the Orion life support and propulsion systems.[34]

One of the advantages of an NRHO is the minimal amount of communications blackout with the Earth.

Gateway will be the first mini-space station to be both human-rated, and autonomously operating most of the time in its early years, as well as being the first deep-space station, far from Low Earth orbit. This will be enabled by more sophisticated executive control software than on any prior space station, which will monitor and control all systems. The high-level architecture is provided by the Robotics and Intelligence for Human Spaceflight lab at NASA, and implemented at NASA facilities. The Gateway could conceivably also support in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) development and testing from lunar and asteroid sources,[35] and would offer the opportunity for gradual buildup of capabilities for more complex missions over time.[36]

Structure

For supporting the first crewed mission to the station (Artemis 3) planned for 2024, the Gateway will be a minimalistic mini-space station composed of only two modules: the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) and the Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO).[37][38] Various components of the Gateway were originally planned to be assembled using the Space Launch System (SLS) as co-manifested flights with the Orion spacecraft,[39] but will now be launched on commercial launch vehicles.[40] According to Roscosmos, they may also use Proton-M and Angara-A5M heavy launchers to fly payloads or crew;[13] however, this is no longer on the agenda.[41] All modules will be connected using the International Docking System Standard.[42] Both PPE and HALO will be assembled on Earth and launched together on a single launcher in January 2024,[43] and they are expected to reach lunar orbit after nine to ten months.[44] The Canadian Space Agency, the European Space Agency and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency plan to participate in the Gateway project, contributing a robotic arm, refueling and communications hardware, and habitation and research capacity. Those international elements will launch after the PPE and HALO are placed into lunar orbit.[45]

Planned modules

- The Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) started development at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory during the now canceled Asteroid Redirect Mission. The original concept was a robotic, high performance solar electric spacecraft that would retrieve a multi-ton boulder from an asteroid and bring it to lunar orbit for study.[46] When ARM was canceled, the solar electric propulsion was repurposed for the Gateway.[47][48] The PPE will allow access to the entire lunar surface and act as a space tug for visiting craft.[29] It will also serve as the command and communications center of the Gateway.[49][50] The PPE is intended to have a mass of 8-9 tons and the capability to generate 50 kW [23] of solar electric power for its ion thrusters, which can be supplemented by chemical propulsion.[51] It is currently planned to launch on a commercial launch vehicle in January 2024 with the HALO module.[43][52][53][54][55] In May 2019, Maxar Technologies was contracted by NASA to manufacture this module, which will also supply the station with electrical power and is based on Maxar's 1300 series satellite bus. The PPE will use Advanced Electric Propulsion System (AEPS) Hall-effect thrusters.[56][57] Maxar was awarded a firm-fixed price contract of US$375 million to build the PPE. NASA is supplying the PPE with an S-band communications system to provide a radio link with nearby vehicles and a passive docking adapter to receive the Gateway's future utilization module.[58]

- The Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO),[59][60] also called the Minimal Habitation Module (MHM) and formerly known as the Utilization Module,[61] will be built by Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems (NGIS).[37][62] A commercial launch vehicle will launch HALO in January 2024 along with the PPE module.[43][52][53] The HALO is based directly on a Cygnus Cargo resupply module[37][63] to the outside of which radial docking ports, body mounted radiators (BMRs), batteries and communications antennae will be added. The HALO will be a scaled-down habitation module,[64] yet it will feature a functional pressurized volume providing sufficient command, control and data handling capabilities, energy storage and power distribution, thermal control, communications and tracking capabilities, two axial and up to two radial docking ports, stowage volume, environmental control and life support systems to augment the Orion spacecraft and support a crew of four for at least 30 days.[62] On 5 June 2020, Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems was awarded a contract, by NASA, of US$187 million to complete the preliminary design of HALO. NASA will sign a separate contract with Northrop for the fabrication of the HALO, and for integration with the PPE, being built by Maxar.[65]

- The European System Providing Refueling, Infrastructure and Telecommunications (ESPRIT) service module will provide additional xenon and hydrazine capacity, additional communications equipment, and an airlock for science packages.[2] It will have a mass of approximately 4,000 kg (8,800 lb), and a length of 3.91 m (12.8 ft).[66]ESA has awarded two parallel design studies one mostly led by Airbus in partnership with Comex and OHB [67] and one led by Thales Alenia Space.[68] The construction of the module was approved in November 2019.[69][70] On 14 October 2020, Thales Alenia Space announced that they had been selected by ESA to build the ESPRIT module.[71][72] Early 2021, Thales Alenia Space announced effective contract signature.[73] The ESPRIT module will consist of two parts. The first part, called the Halo Lunar Communication System (HLCS) will provide the communications for the station. It will launch in 2024 pre-attached to the HALO module, for which Thales has separately been awarded a contract by NASA to construct its hull and micrometeoroid protection. The second part, called the ESPRIT Refueling Module (ERM), will contain the pressurised fuel tanks, docking ports and small windowed habitation corridor and launch in 2027.[71][72]

Thales Alenia Space Gateway team in front of sea-facing facilities in Cannes, France

Thales Alenia Space Gateway team in front of sea-facing facilities in Cannes, France

- The International Habitation Module (I-HAB) will be an additional habitation module built by ESA in collaboration with Japan.[69] Together with the HALO module, they will provide a combined 125 m3 (4,400 cu ft) of habitable volume to the station, after 2024.[2] On 14 October 2020, Thales Alenia Space announced that they had been selected by ESA to build the I-HAB module slated for launch in 2026. The module will also feature contributions from the other station partners, including a life support system from JAXA, avionics and software from NASA and robotics from Canadian Space Agency (CSA).[71][72]

Proposed modules

The concept for the Gateway is still evolving, and is intended to include the following modules:[74]

- The Gateway Logistics Modules will be used to refuel, resupply and provide logistics on board the mini-space station. The first logistics module sent to the Gateway will also arrive with a robotic arm, which will be built by the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).[75][76]

- The Gateway Airlock Module will be used for performing extravehicular activities outside the mini-space station and would have the docking port for the proposed Deep Space Transport.

- The Canadarm3, a robotic remote manipulator arm, similar to the Space Shuttle Canadarm and International Space Station Canadarm2. The arm is to be the contribution of the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) to this international endeavor. CSA contracted MDA (MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates) to build the arm. MDA previously built Canadarm2, while its former subsidiary, Spar Aerospace, built Canadarm.[77][78][79][80]

Construction

Crewed flights to the Gateway are expected to use Orion and SLS, while other missions are expected to be done by commercial launch providers. In March 2020, NASA announced SpaceX with its future spacecraft Dragon XL as a first commercial partner to deliver supplies to the Gateway.[81] The two modules (PPE and HALO) will be launched together on a single launcher in January 2024.[43]

| Year | Mission objective | Mission name | Launch vehicle | Human/robotic elements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 2024[43] | Launch of the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) [82] | Mini-space station Gateway | Commercial launch vehicle | Robotic |

| January 2024[43][83][84] | Launch of the Habitation, and Logistics Outpost (HALO) to the Gateway | Mini-space station Gateway | Commercial launch vehicle | Robotic |

| 2024 | Delivery of expendable or reusable ascent element for Artemis 3 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2024 | Delivery of expendable or reusable transfer element for Artemis 3 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2024 | Delivery of expendable or reusable descent element for Artemis 3 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2024 | Delivery of ESPRIT and Utilization modules | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| October 2024 | Delivery of Orion MPCV and logistics module | Artemis 3 | SLS Block 1 | Crewed |

| 2025 | (Proposed) delivery of expendable ascent element for Artemis 4 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2025 | (Proposed) delivery of expendable descent element for Artemis 4 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2025 | (Proposed) delivery of expendable transfer element for Artemis 4 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| March 2026[85] | (Proposed) Delivery of Orion MPCV and logistics module | Artemis 4 | SLS Block 1B | Crewed |

| 2026 | Delivery of iHAB to the Gateway | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2026 | (Proposed) delivery of reusable ascent element for Artemis 5 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2026 | (Proposed) delivery of reusable transfer element for Artemis 5 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2026 | (Proposed) delivery of descent element for Artemis 5 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2026 | (Proposed) Delivery of Orion MPCV and logistics module | Artemis 5 | SLS Block 1B | Crewed |

| 2027 | (Proposed) delivery of a Gateway station module | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2027 | (Proposed) refueling of ascent element for Artemis 6 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2027 | (Proposed) refueling of transfer element for Artemis 6 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2027 | (Proposed) delivery of descent module for Artemis 6 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2027 | (Proposed) Delivery of Orion MPCV and logistics module | Artemis 6 | SLS Block 1B | Crewed |

| 2028 | (Proposed) delivery of a Gateway station module | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2028 | (Proposed) refueling of ascent element for Artemis 7 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2028 | (Proposed) refueling of transfer element for Artemis 7 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2028 | (Proposed) delivery of descent module for Artemis 7 | Artemis support mission | Commercial launch vehicles | Robotic |

| 2028 | (Proposed) Delivery of Orion MPCV and logistics module | Artemis 7 | SLS Block 1B | Crewed |

Reactions

NASA officials promote the Gateway as a "reusable command module" that could direct activities on the lunar surface.[86] However, the Gateway has received both positive and negative reactions from space professionals.

Michael D. Griffin, a former NASA administrator, said that the Gateway could be useful only after there are facilities on the Moon producing propellant that could be transported to the Gateway. Griffin thinks that after that is achieved, the Gateway would then serve as a fuel depot.[86]

Former NASA Associate Administrator Doug Cooke wrote in an article on The Hill stating, "NASA can significantly increase speed, simplicity, cost and probability of mission success by deferring Gateway, leveraging SLS, and reducing critical mission operations". He also wrote, "NASA should launch the lander elements (ascent and descent/transfer) on a SLS Block 1B. If an independent transfer element is required, it can be launched on a commercial launcher".[87] George Abbey, a former director of NASA's Johnson Space Center said, "The Gateway is, in essence, building a space station to orbit a natural space station, namely the Moon. [...] If we are going to return the Moon, we should go directly there, not build a space station to orbit it".[88]

Former NASA astronaut Terry W. Virts, who was a pilot of STS-130 aboard Space Shuttle Endeavour and commander of the ISS on Expedition 43, wrote in an Op-ed on Ars Technica that the Gateway would "shackle human exploration, not enable it". He also said, "If we don't have the goal [of Gateway], we are putting the proverbial chicken before the egg by developing "Gemini" before we know what "Apollo" will look like. Regardless of a future destination, as someone who lived on the ISS for 200 days, I cannot envision a new technology that would be developed or validated by building another modular space station. Without a specific goal, we're unlikely to ever identify one". Terry further criticized NASA for abandoning its planned goal of separating crew from cargo, which was put in place following the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003.[89] Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin stated that he is "quite opposed to the Gateway" and that "using the Gateway as a staging area for robotic or human missions to the lunar surface is absurd". Aldrin also questioned the benefit of the idea to "send a crew to an intermediate point in space, pick up a lander there and go down". On the other hand, Aldrin expressed support for Robert Zubrin's Moon Direct concept which involves lunar landers traveling from Earth orbit to the lunar surface and back.[90]

Pei Zhaoyu, deputy director of the Lunar Exploration and Space Program Center of the China National Space Administration (CNSA), concluded that, from a cost-benefit standpoint, the Gateway would have "low cost-effectiveness".[91] Pei said the Chinese plan is to focus on a national research station on the surface.[92] In July 2019, Pei announced that China was holding discussions with Russia and the ESA on international co-operation [93] and in August 2020 unveiled China's concept; the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) [94] with co-operation from Russia and tentative agreement from ESA.

Mars advocacy and Mars Society founder Robert Zubrin called the Gateway "NASA's worst plan yet" in an article in the National Review. He said, "We do not need a lunar-orbiting station to go to the Moon. We do not need such a station to go to Mars. We do not need it to go to near-Earth asteroids. We do not need it to go anywhere. Nor can we accomplish anything in such a station that we cannot do in the Earth-orbiting International Space Station, except to expose human subjects to irradiation – a form of medical research for which a number of Nazi doctors were hanged at Nuremberg". Zubrin also stated, "If the goal is to build a Moon base, it should be built on the surface of the Moon. That is where the science is, that is where the shielding material is, and that is where the resources to make propellant and other useful things are to be found".[95]

Retired aerospace engineer Gerald Black stated that the Gateway is "useless for supporting human return to the lunar surface and a lunar base". He added that it was not planned to be used as a rocket fuel depot and that stopping at the Gateway on the way to or from the Moon would serve no useful purpose and cost propellant.[96]

Mark Whittington, who is a contributor to The Hill newspaper and an author of several space exploration studies, stated in an article that the "lunar orbit project doesn't help us get back to the Moon". Whittington also pointed out that a lunar orbiting space station was not utilized during the Apollo program and that a "reusable lunar lander could be refueled from a depot on the lunar surface and left in a parking orbit between missions without the need for a big, complex space station".[97]

Astrophysicist Ethan Siegel wrote an article in Forbes titled "NASA's Idea For A Space Station In Lunar Orbit Takes Humanity Nowhere". Siegel stated that "Orbiting the Moon represents barely incremental progress; the only scientific "advantages" to being in lunar orbit as opposed to low Earth orbit are twofold: 1. You're outside of the Van Allen belts. 2. You're closer to the lunar surface", reducing the time delay. His final opinion was that the Gateway is "a great way to spend a great deal of money, advancing science and humanity in no appreciable way".[98]

On 10 December 2018, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said at a presentation "There are people who say we need to get there, and we need to get there tomorrow", speaking of a crewed mission to the Moon, countering with "What we're doing here at NASA is following Space Policy Directive 1", speaking of the Gateway and following up with "I would argue that we got there in 1969. That race is over, and we won. The time now is to build a sustainable, reusable architecture. [...] The next time we go to the moon, we're going to have American boots on the moon with the American flag on their shoulders, and they're going to be standing side-by-side with our international partners who have never been to the moon before".[99]

Dan Hartman, the program manager for Gateway, on 30 March 2020, told Ars Technica that the benefits of using Gateway are extending the mission duration, buying down risk, providing research capability and the capability to re-use ascent modules. "When you go single, I'll say direct mission to the Moon, you're limited on the supplies, either with the Lander or with Orion. With the Gateway, with just with one logistics module, we think we can extend to about twice the mission duration, so 30 days to 60 days. Obviously, the more crew time you have in lunar orbit helps us with research in the human aspects of living in deep space. The more duration we have, certainly that'll help us buy down significant risk with the extreme environments that we're going to be subjecting our crews to. Because we've got to go figure out how to operate in deep space. Obviously we'll demonstrate new hardware and offer that sustainable flexible path for our Lunar Lander system. With the Gateway, the thinking is we'll be able to reuse the ascent modules potentially multiple times. And again, if we can get mission duration beyond the 30 days, it's going to offer us some additional environmental capabilities. We think it's a tremendous risk buy down asset, not only to explore the Moon sustainably, but to prove out some things that we need to do to get to Mars".[100]

See also

- CAPSTONE (spacecraft) – A NASA satellite to test the Lunar Gateway orbit

- Commercial Resupply Services – Series of contracts awarded by NASA from 2008-present for delivery of cargo and supplies to the ISS

- Exploration Gateway Platform – Original station design concept of the Lunar Gateway

- Lunar Orbital Station – Proposed Russian space station on Moon orbit

- Lunar outpost (NASA) – Concepts for an extended human presence on the Moon

- Orbital Piloted Assembly and Experiment Complex – Proposed Russian space station

- Project Prometheus – NASA nuclear electric propulsion project 2003-2006

References

- Mahoney, Erin (30 October 2018). "Q&A: NASA's New Spaceship". NASA. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Sloss, Philip (11 September 2018). "NASA updates lunar Gateway plans". NASASpaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- Angelic halo orbit chosen for humankind's first lunar outpost. Archived 11 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine European Space Agency, Published by PhysOrg 19 July 2019

- Jackson, Shanessa (11 September 2018). "Competition Seeks University Concepts for Gateway and Deep Space Exploration Capabilities". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Davis, Jason (26 February 2018). "Some snark (and details!) about NASA's proposed lunar space station". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- Yuhas, Alan (12 February 2018). "Trump's Nasa budget: flying 'Jetson cars' and a return to the Moon". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/fy_2021_budget_book_508 Archived 27 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine - p. 4|access-date=2020-04-01

- Foust, Jeff (12 June 2018). "Senate bill restores funding for NASA science and technology demonstration missions". Space News. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- "NASA just got its best budget in a decade". planetary.org. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Mahoney, Erin (24 August 2018). "NASA Seeks Ideas for Scientific Activities Near the Moon". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Kathryn Hambleton. "Deep Space Gateway to Open OpportunitiesArtemis for Distant Destinations". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "РОСКОСМОС - NASA СОВМЕСТНЫЕ ИССЛЕДОВАНИЯ ДАЛЬНЕГО КОСМОСА (ROSCOSMOS - NASA JOINT RESEARCH OF FAR COSMOS)". Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Weitering, Hanneke (27 September 2017). "NASA and Russia Partner Up for Crewed Deep-Space Missions". Space.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- NASA (2 May 2018). "Gateway Memorandum for the Record" (PDF). nasa.gov. NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Robert Z. Pearlman (18 September 2019). "NASA Reveals New Gateway Logo for Artemis Lunar Orbit Way Station". space.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Gebhardt, Chris (6 April 2017). "NASA finally sets goals, missions for SLS – eyes multi-step plan to Mars". nasaspaceflight.com. NASASpaceflight. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- Robyn Gatens, Jason Crusan. "Cislunar Habitation and Environmental Control and Life Support System". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Russia skeptical about participating in lunar Gateway". SPACENEWS. 12 October 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ""Роскосмос" подтвердил выход из лунного проекта Gateway". Interfax. 25 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- Doug Messier on (11 August 2016). "A Closer Look at NextSTEP-2 Deep Space Habitat Concepts". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- Warner, Cheryl (2 May 2018). "NASA's Lunar Outpost will Extend Human Presence in Deep Space". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - NASA Seeks Information on Developing Deep Space Gateway Module Archived 7 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine Jeff Foust, Space.com 29 July 2017

- Foust, Jeff (3 November 2017). "NASA issues study contracts for Deep Space Gateway element". SpaceNews. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Program and Presenter Information". Lunar and Planetary Institute. Universities Space Research Association. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- "Students Blaze New Trails in NASA Space Exploration Design Competition". NASA. 21 June 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jimi Russell. "NASA Selects Studies for Gateway Power and Propulsion Element". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Erin Mahoney. "NextSTEP Partners Develop Ground Prototypes to Expand our Knowledge of Deep Space Habitats". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Overview of the Development and Mission Application of the Advanced Electric Propulsion System (AEPS) Archived 2 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Daniel A. Herman, Todd A. Tofil, Walter Santiago, Hani Kamhawi, James E. Polk, John S. Snyder, Richard R. Hofer, Frank Q. Picha, Jerry Jackson and May Allen. NASA, NASA/TM—2018-219761; 35th International Electric Propulsion Conference. Atlanta, Georgia, 8-12 October 2017. Accessed 27 July 2018

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "NASA Awards Artemis Contract for Lunar Gateway Power, Propulsion" (Press release). NASA. 23 May 2019. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - NASA updates Lunar Gateway plans Archived 6 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine Philip Sloss, NASASpaceflight.com 11 September 2018

- Gateway Update Archived 3 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine NASA Advisory Council, Human Exploration and Operations Committee, Jason Crusan, 7 December 2018

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Halo orbit selected for Gateway space station. Archived 11 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine David Szondy, New Atlas 18 July 2019

- Foust, Jeff (16 September 2019). "NASA cubesat to test lunar Gateway orbit". SpaceNews. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Whitley, Ryan; Martinez, Roland (21 October 2015). "Options for Staging Orbits in Cis-Lunar Space" (PDF). nasa.gov. NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20180002054.pdf Archived 31 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine Research Possibilities Beyond Deep Space Gateway] David Smitherman, Debra Needham, Ruthan Lewis, NASA February 28, 2018

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/march_2017_nac_charts_architecturejmf_rev_3_tagged.pdf Archived 2 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate - Architecture Status] Jim Free NASA 28 March 2017

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Foust, Jeff (23 July 2019). "NASA to sole source Gateway habitation module to Northrop Grumman". SpaceNews. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- NASA's Grand Plan for a Lunar Gateway Is to Start Small. Archived 23 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine Mike Wall, Space.com - 24 May 2019

- Godwin, Curt (1 April 2017). "NASA's human spaceflight plans come into focus with announcement of Deep Space Gateway". Spaceflight Insider. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "America to the Moon 2024 - Optimized" (PDF). nasa.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- NASA Unveils the Keys to Getting Astronauts to Mars and Beyond Archived 27 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine Neel V. Patel, The Inverse - April 4, 2017

- "Report No. IG-21-004: NASA's Management of the Gateway Program for Artemis Missions" (PDF). OIG. NASA. 10 November 2020. pp. 5–7. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- Foust, Jeff (14 May 2020). "NASA refines plans for launching Gateway and other Artemis elements". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- https://spaceflightnow.com/2020/05/06/nasa-plans-to-launch-first-two-gateway-elements-on-same-rocket/ Archived 6 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine - 6 Mai 2020

- Greicius, Tony (20 September 2016). "JPL Seeks Robotic Spacecraft Development for Asteroid Redirect Mission". NASA. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "NASA closing out Asteroid Redirect Mission". SpaceNews. 14 June 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Asteroid Redirect Robotic Mission". jpl.nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Deep Space Gateway and Transport: Concepts for Mars, Moon Exploration Unveiled". Science News. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Clark, Stephen. "NASA chooses Maxar to build keystone module for lunar Gateway station". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Chris Gebhardt. "NASA finally sets goals, missions for SLS – eyes multi-step plan to Mars". NASASpaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://spaceflightnow.com/2020/05/06/nasa-plans-to-launch-first-two-gateway-elements-on-same-rocket/ Archived 6 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine - 7 May 2020

- "NASA FY 2019 Budget Overview" (PDF). NASA. 9 February 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

Supports launch of the Power and Propulsion Element on a commercial launch vehicle as the first component of the LOP-Gateway.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Foust, Jeff (30 March 2018). "NASA considers acquiring more than one gateway propulsion module". SpaceNews. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Foust, Jeff (23 May 2019). "NASA selects Maxar to build first Gateway element". SpaceNews. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Status of Advanced Electric Propulsion Systems for Exploration Missions. Archived 13 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine R. Joseph Cassady, Sam Wiley, Jerry Jackson, Aerojet Rocketdyne, October 2018

- Clark, Stephen (24 May 2019). "NASA chooses Maxar to build keystone module for lunar Gateway station". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- Foust, Jeff (30 August 2019). "ISS partners endorse modified Gateway plans". SpaceNews. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- NASA Asks American Companies to Deliver Supplies for Artemis Moon Missions. NASA Press Release M019-14, 23 August 2019

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Planetary Society. "Humans in Deep Space". planetary.org. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Justification for other than full and open competition (JOFOC) for the Minimal Habitation Module (MHM)". Federal Business Opportunities. Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Gebhardt, Chris. "Northrop Grumman outlines HALO plans for Gateway's central module". NASASpaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Messier, Doug (23 July 2019). "NASA Awards Contract to Northrop Grumman for Gateway Habitat Module". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "NASA signs Gateway habitat design contract with Northrop Grumman". Spaceflight Now. 9 June 2020. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ESA develops logistics vehicle for cis-lunar outpost Archived 4 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine Anatoly Zak, Russian Space Web 8 September 2018

- Comex and Airbus join forces around a module of the future lunar station. Archived 29 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine Comex, press release, 21 November 2018

- "Back to the Moon, a step towards future exploration missions". Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Funding Europe's space ambitions. Archived 29 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine Jeff Foust, The Space Review December 2019

- Hera mission is approved as ESA receives biggest ever budget. Archived 10 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine Kerry Hebden, Room' 29 November 2019

- "Europe steps up contributions to Artemis Moon plan". BBC. 14 October 2020. Archived from the original on 14 October 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- "Thales Alenia Space on its way to reach the Moon". thalesgroup.com. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- https://www.thalesgroup.com/en/worldwide/space/news/thales-alenia-space-heart-lunar-industrial-challenges

- Cursan, Jason (27 March 2018). "Future Human Exploration Planning:Lunar Orbital Platform – Gateway and Science Workshop Findings" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Mortillaro, Nicole (28 February 2019). "Canada's heading to the moon: A look at the Gateway". CBC News. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "Canadian Space Agency to build robotic arms for lunar space station". Global News. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- "About Canadarm3". Canadian Space Agency. 16 December 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- Canadian Space Agency (26 June 2020). "Building the next Canadarm". Government of Canada.

- "Canadian Space Agency awards Canadarm3 contract worth $22.8 million to MDA". CTV News. The Canadian Press. 8 December 2020.

- MDA (8 December 2020). "MDA Announces Contract for Canadarm3 on NASA-led Gateway". Yahoo News. CNW.

- "SpaceX wins NASA commercial cargo contract for lunar Gateway". 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Daines, Gary (1 December 2016). "Crew Will Mark Important Step on Journey to Mars". nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Foust, Jeff (23 July 2019). "NASA to sole source Gateway habitation module to Northrop Grumman". SpaceNews. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Messier, Doug (23 July 2019). "NASA Awards Contract to Northrop Grumman for Lunar Gateway Habitat Module". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "NASA's Management of the Gateway Program for Artemis Missions" (PDF). OIG. NASA. 10 November 2020. p. 3. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

Artemis IV is scheduled to launch in March 2026 (as of August 2020).

- Is the Gateway the right way to the Moon? Jeff Foust, SpaceNews 25 December 2018

- Cooke, Doug. "Getting back to the moon requires speed and simplicity". The Hill. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Abbey, George. "The Moon is "a God-given space station orbiting Earth" [Opinion]". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- "Op-ed: The Deep Space Gateway would shackle human exploration, not enable it". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- Foust, Jeff. "Advisory group skeptical of NASA lunar exploration plans". SpaceNews. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- Berger, Eric. "Chinese space official seems unimpressed with NASA's lunar gateway". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- Kapoglou, Angeliki. "twitter.com/Capoglou". twitter.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-07/22/c_138248065.htm

- https://spacenews.com/china-is-aiming-to-attract-partners-for-an-international-lunar-research-station/

- "NASA's Worst Plan Yet". National Review. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- The Lunar Orbital Platform – Gateway: an unneeded and costly diversion Archived 21 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine Gerald Black, The Space Review 14 May 2018

- Whittington, Mark. "NASA's unnecessary US$504 million lunar orbit project doesn't help us get back to the Moon". The Hill. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- Siegel, Ethan. "NASA's Idea For A Space Station In Lunar Orbit Takes Humanity Nowhere". Forbes. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Foust, Jeff (15 December 2018). "Is the Gateway the right way to the moon?". spacenews.com. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Eric, Berger (30 March 2020). "NASA officials outline plans for building a lunar Gateway in the mid-2020s". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

External links

- Deep Space Gateway to Open Opportunities for Distant Destinations - NASA Moon to Mars

- First human outpost near the Moon – RussianSpaceWeb page about the Gateway

- History of the Gateway planning

.svg.png.webp)