Hurdia

Hurdia is an extinct genus of hurdiid radiodont that lived 505 million years ago during the Cambrian Period. As a radiodont like Peytoia and Anomalocaris, it is part of the ancestral lineage that led to euarthropods.[1]

| Hurdia | |

|---|---|

| |

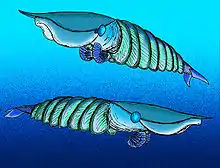

| Artist's reconstruction | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | †Dinocaridida |

| Order: | †Radiodonta |

| Family: | †Hurdiidae |

| Genus: | †Hurdia Walcott, 1912 |

| Type species | |

| †Hurdia victoria Walcott, 1912 | |

| Other species | |

| |

Description

Hurdia was one of the largest organisms in the Cambrian oceans, reaching approximately 20 cm (8 inches) in length.[1] Its head bore a pair of rake-like frontal appendages which shovelled food into its pineapple-ring-like mouth (oral cone). Like other hurdiids, Hurdia bore a large frontal carapace protruding from its head composed of three sclerites: a central component known as the H-element and two lateral components known as P-elements. The function of this organ remains mysterious; it cannot have been protective as there was no underlying soft tissue.[2] Body flaps ran along the sides of the organisms, from which large gills were suspended.

Ecology

Hurdia was a predator, or possibly a scavenger. Its frontal appendages are flimsier than those of Anomalocaris, suggesting that it fed on less robust prey. It displayed a cosmopolitan distribution; it has been recovered from the Burgess shale as well as sites in the USA, China and Europe.[1]

Taxonomic history

Hurdia was named in 1912 by Charles Walcott, with two species, the type species H. victoria and a referred species, H. triangulata.[3] The genus name refers to Mount Hurd.[3] It is possible that Walcott had described a specimen the year prior as Amiella, but the specimen is too fragmentary to identify with certainty, so Amiella is a nomen dubium.[4] Walcott's original specimens consisted only of H-elements of the frontal carapace, which he interpreted as being the carapace of an unidentified type of crustacean. P-elements of the carapace were described as a separate genus, Proboscicaris, in 1962.

In 1996, then-curator of the Royal Ontario Museum Desmond H. Collins erected the taxon Radiodonta to encompass Anomalocaris and its close relatives, and included both Hurdia and Proboscicaris in the group.[5] He subsequently recognized that Proboscicaris and Hurdia were based on different parts of the same animal, and recognized that a specimen previously assigned to Peytoia was also a specimen of the species.[4] He presented his ideas in informal articles,[6][7] and it was not until 2009, after three years of painstaking research, that the complete organism was reconstructed.[1][8][9][10]

Sixty-nine specimens of Hurdia are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they comprise 0.13% of the community.[11]

References

- Daley, A. C., Budd, G. E., Caron, J. B., Edgecombe, G. D., Collins, D. (2009). "The Burgess Shale anomalocaridid Hurdia and its significance for early euarthropod evolution". Science. 323 (5921): 1597–1600. Bibcode:2009Sci...323.1597D. doi:10.1126/science.1169514. PMID 19299617.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "ROM collections reveal 500 million-year-old monster predator" (Press release). Royal Ontario Museum. 2009-03-20. Archived from the original on 2019-02-15.

- Walcott, Charles D. (1912-03-13). "Middle Cambrian Branchiopoda, Malacostraca, Trilobita, and Merostomata". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 57 (6).

- Daley, Allison C.; Budd, Graham E.; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2013). "Morphology and systematics of the anomalocaridid arthropod Hurdia from the Middle Cambrian of British Columbia and Utah". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 11 (7): 743–787. doi:10.1080/14772019.2012.732723.

- Collins, Desmond (1996). "The "Evolution" of Anomalocaris and Its Classification in the Arthropod Class Dinocarida (nov.) and Order Radiodonta (nov.)". Journal of Paleontology. 70 (2): 280–293. JSTOR 1306391.

- D. Collins, in North American Paleontological Convention, Chicago, Abstracts with Programs, S. Lidgard, P. R. Crane, Eds. (The Paleontological Society, Special Publication 6, Chicago, IL, 1992), p. 66, 11.

- D. Collins (1999). "Dinocarids: the first monster predators on earth". Rotunda. Vol. 32. Royal Ontario Museum. p. 25.

- Fossil fragments reveal 500-million-year-old monster predator.

- New animal discovered by Canadian researcher.

- Scientists identify T-Rex of the sea

- Caron, Jean-Bernard; Jackson, Donald A. (October 2006). "Taphonomy of the Greater Phyllopod Bed community, Burgess Shale". PALAIOS. 21 (5): 451–65. doi:10.2110/palo.2003.P05-070R. JSTOR 20173022.