Ibibio people

The Ibibio people are a coastal people in southern Nigeria.[2] They are mostly found in Akwa Ibom, Cross River, and on the Eastern Part of Abia. They are related to the Annang Igbo and Efik peoples. During the colonial period in Nigeria, the Ibibio Union asked for recognition by the British as a sovereign nation (Noah, 1988). The Annang, Efik, Ekid, Oron and Ibeno share personal names, culture, and traditions with the Ibibio, and speak closely related varieties (dialects) of Ibibio which are more or less mutually intelligible.[3] The Ekpo/Ekpe society is a significant part of the Ibibio political system. They use a variety of masks to execute social control. Body art plays a major role in Ibibio art.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 10 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 8,482,000 | |

| 39,000 | |

| 2,700 | |

(Afro-Trinidadian and Tobagonian) | 371 (1813)[1] |

| Languages | |

| Ibibio, English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, traditional, | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Efik, Anaang, Ejagham, Oron, Igbo, Ijaw, Bahumono | |

Origin

The Ibibio people are reputed to be the earliest inhabitants of the south southern Nigeria. It is estimated that they arrived at their present home around 7000 B.C. In spite of the historical account, it is not clear when the Ibibio arrived at state. According to some scholars, they might have come from the central Benue valley, particularly, the Jukun influence in the old Calabar at some historical time period. Another pointer is the wide-spread use of the manila, a popular currency used by the Jukuns. Coupled with this is the Jukun southern drive to the coast which appears to have been recently compared with the formation of Akwa Ibom settlements in their present location.[4]

Another version described that the Cameroon will offer a more concise explanation of the Ibibio migration story. This was corroborated by oral testimonies by field workers who say that the core Ibibio people were of the Afaha lineage whose original home was Usak Edet in the Cameroon. This was premised on the fact that among the Ibibio people, Usak Edet is popularly known as Edit Afaha (Afaha’s Creek) which reflects the fact that Ibibio people originated from Usak Edet. After the first bulk of the people arrived in what later became Nigeria, they settled first at Ibom then in Arochukwu. The Ibibio must have lived in Ibom for quite some time. As a result of clashes with the Igbo people, culminating in the famous ‘Ibibio War’, which took place about 1300 and 1400 A.D., they left Ibom and moved to the present day Ibibio land.[5]

Geography

The Ibibio people are found predominantly in Akwa Ibom state and are related to the Anaang community, the Ibibio community and the Eket and Oron communities, although other groups usually understand the Ibibio language. Because of the larger population of the Ibibio people, they hold political control over Akwa-Ibom State, but the government is shared with the Anaangs, Eket and Oron. The political system follows the traditional method of consensus. Even though elections are held, practically, the political leaders are pre-discussed in a manner that is benefiting to all.

Location of Ibibioland

The Ibibio people are located in the South South geopolitical zone of Nigeria also known as Coastal Southeastern Nigeria. Prior to the existence of Nigeria as a nation, the Ibibio people were self-governed. The Ibibio people became a part of the Eastern Nigeria of Nigeria under British colonial rule. During the Nigerian Civil War, the Eastern region was split into three states. Southeastern State of Nigeria was where the Ibibio were located, one of the original twelve states of Nigeria after Nigerian independence. The Efik, Anaang, Oron, Eket, and their brothers and sisters of the Ogoja District, were also in the Southeastern State. The state (Southeastern State) was later renamed Cross Rivers State. On 23 September 1987, by Military Decree No.24, Akwa Ibom State was carved out of the then Cross Rivers State as a separate state. Cross Rivers State remains as one of neighbouring states.

Southwestern Cameroon was a part of the present Cross River State and Akwa Ibom State of Nigeria. During the then Eastern Region of Nigeria, it got partitioned into Cameroon in a 1961 plebiscite. This resulted in the Ibibio, Efik, and Annang being divided between Nigeria and Cameroon. However, the leadership of the Northern Region of Nigeria was able to keep the "Northwestern section" during the plebiscite that is now today's Nigerian Adamawa and Taraba states.

Political system

Traditionally Ibibio society consists of communities that are made up of large families with blood affinity each ruled by their constitutional and religious head known as the Ikpaisong. The Obong Ikpaisong ruled with the Mbong Ekpuk (Head of the Families) which together with the heads of the cults and societies constitute the 'Afe or Asan or Esop Ikpaisong' (Traditional Council or Traditional Shrine or Traditional Court'). The decisions of the Obong Ikpaisong were enforced by members of the Ekpo or Obon society who act as messengers of the spirits and the military and police of the community. Ekpo members are always masked when performing their policing duties. Although their identities are almost always known, fear of retribution from the ancestors prevents most people from accusing those members who overstep their social boundaries, effectively committing police brutality. Membership is open to all Ibibio males, but one must have access to wealth to move into the politically influential grades. The main purpose of Ekpo is to protect its people and act as a defense against potential attackers. They are concerned with issues and emergencies that pertain to the safety of the town as a whole. In addition, it serves as an outlet for men to productively use energy to benefit everyone.[6] In the months of June through December, the Ekpo society plays a large role in the community's life. Many activities such as farming, shopping, and obtaining food and water are prohibited on days in which the masks are out and being performed. Crimes also carry heavier consequences during this time period.[6] While the punishments are more lax today, a person caught stealing during this time period in the 1940s would be killed by members of the Ekpo.[6] The chief will send masked individuals to confront a rule-breaker if the need arises. It is known as a secret society despite the fact that the purpose and activities are widely known by the village. This is due to the fact that everyone must abide by certain laws during Ekpo season. The most important secrets are a series of code words and dance steps taught to initiates and used by members. Knowing these secrets allows members to travel freely during the season, and being caught traveling without knowing the secret terms and dance will result in being arrested.[6]

The Obon society, with its strong enticing traditional musical prowess and popular acceptability, openly executes its mandates with musical procession and popular participation by members which comprises children, youth, adults and brave elderly women.

Religion

Pre-Colonial Era

Ibibio religion (Inam) was of two dimensions, which centered on the pouring of libation, sacrifice, worship, consultation, communication and invocation of the God of Heaven (Abasi Enyong), God of the Earth (Abasi Isong) and the Supreme Being (Abasi Ibom) by the Constitutional and Religious King/Head of a particular Ibibio Community who was known from the ancient times as the Obong-Ikpaisong (the word 'Obong Ikpaisong' directly interpreted means King of the Principalities of the Earth' or 'King of the Earth and the Principalities' or Traditional Ruler).[7] The second dimension of Ibibio Religion centered on the worship, consultation, invocation, sacrifice, appeasement, etc. of the God of the Heaven (Abasi Enyong) and the God of the Earth (Abasi Isong) through various invisible or spiritual entities (me Ndem) of the various Ibibio Division such as Atakpo Ndem Uruan Inyang, Afia Anwan, Ekpo/Ekpe Onyong, Etefia Ikono, Awa Itam, etc. The Priests of these Deities (me Ndem) were the Temple Chief Priests/Priestesses of the various Ibibio Divisions. A particular Ibibio Division could consist of many interrelated autonomous communities or kingdoms ruled by an autonomous Priest-King called Obong-Ikpaisong, assisted by heads of the various large families (Mbong Ekpuk) which make up the Community. These have been the ancient political and religious system of Ibibio people from time immemorial. Tradition, interpreted in Ibibio Language, is 'Ikpaisong'. Tradition (Ikpaisong) in Ibibio Custom embodies the Religious and Political System. The word 'Obong' in Ibibio language means 'Ruler, King, Lord, Chief, Head' and is applied depending on the Office concern. In reference to the Obong-Ikpaisong, the word 'Obong' means 'King'. In reference to the Village Head, the word means 'Chief'. In reference to the Head of the Families (Obong Ekpuk), the word means 'Head' In reference to God, the word means 'Lord'. In reference to the Head of the various societies - e.g. 'Obong Obon', the word means 'Head or Leader'.

Sacred Lands (Akai)

Scattered throughout each village were sacred lands, akai (forest). They were called akai because no one was permitted to clear them for cultivation. All burial grounds, shrines for the village deities and spots for secret societies such as Ekpo Onyoho, Ekpe, Ekoong, Idiong, Ekong, and Obon, were sacred. Everything in these places were equally sacred. Non-members of the secret societies were not permitted to enter the spots set aside for such secret societies, even for the collection of firewood, sticks, fruits (like mkpook), vegetables (like afang and odusa) or snails, or to hunt the animals which abounded in the forests. The explanation is simple. If non-members were allowed to enter any secret society akai they might in due course discover the secrets of their time-honoured society, and wicked people might even desecrate the graves of their ancestors hence the ban.

The Soul and Life After Death

Like many Ibibio words, the name Ukpong (Soul) has four meanings. First, ethereal body, secondly, soul, thirdly, spirit, and fourthly, over-soul; the last always lives in the house of Abasi Ibom and it is quite separate from the individuality which between incarnations stays in the country of the dead. Though over-soul and spirit are combined, much of the Spirit is contained in that portion of the ego which is incarnated.

According to Talbot, it is the soul proper that spends part of its time as a were-animal or in a bush-beast in the forest or water and is called Ukpong Ikot, or bush-soul. The shadow is not thought to be connected with the ethereal body but to be an emanation of the soul and therefore to be directly affected by any action on it. The majority of the Ibibio believe that a person's soul can be invoked into his shadow, which is made to appear in a basin of water. The shadow is then speared, his blood is seen in the water in the basin and the man dies.

The Ibibio believe that after death the same kind of existence is led as during life on earth; for example, farmers, blacksmiths, hunters, and fishermen will continue with their former occupations while social intercouse and amusements will also proceed as before. The scenery, houses, crops and animals of the next world have the same appearance as in this world but only those beasts, plants and foodstuffs which have been sacrificed in honour of the dead are transported there. The land of the dead, like that of the living, is believed to be divided into various countries, towns, villages and lineages where different communities of people live as on earth. At death every man goes to the particular part inhabited by his people.

Obot (Nature)

The Ibibio believe in obot, that is, the individual creation of persons by God. If someone is wild, they say he was created that way; if he is kind, again that is how he was created by God to be; if he is poor or rich, that was his lot, etc., so there was nothing anyone could do to alter his lot, for he was moulded that way.

Essien Emana (destiny). The Ibibio also believe in the same way in destiny, essien emana or uwa. For instance, if a person died accidentally, this was how he had died in his previous incarnation and therefore he had to die that way. If he was rich, he was so in his previous incarnation and must be so now; if he was brilliant, that was how he was destined to be, etc. He could, however, reverse the situation if he consulted the Mbia Idiong, who alone could tell him what to do. The diviners could help him pin-point what it was he had done in his previous incarnation which was affecting his present life. They could then prescribe to him what to do to remedy the worsening situation. If the instructions were strictly followed, the position could be reversed, they believed. For instance, if a person had no issue a diviner might tell him that he had killed innocent children in his previous incarnation, and that the parents of the deceased and the general public had cursed him, saying that he would not have any issue and would continue to kill innocent children throughout his incarnations unless he gave certain things as sacrificial offerings. When the Mbia Idiong told him what the things were and he had offered them as sacrifices to Mother Earth, the Ibibio believed the situation would be reversed; otherwise, he would remain childless.

Colonial and Post-Colonial Era

The Ibibio were introduced to Christianity through the work of early missionaries in the nineteenth century. Samuel Bill started his work at Ibeno. He established the Qua Iboe Church which later spread places in the middle belt of Nigeria. Later, other churches were also introduced e.g. The Apostolic church. Independent churches such as Deeper Life Bible Church, came into the area in the second part of the twentieth century. Today Ibibio people are predominantly Christian.

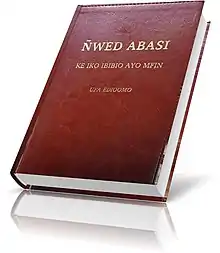

The Bible in Ibibio Language

History was made on the 27th day of August 2020 that the first-ever Ibibio Bible translation was presented at Ibom Hall in Uyo, the capital of Akwa Ibom. Published by the 200-year-old, American based International Bible Society (Biblica), the publishers of the NIV Version.

The Ibibio Bible was translated by Ibibio professors, including Professors Margaret Mary Okon, Bassey Okon, Eno-Abasi Urua, Inimbom Akpan, Udo Etuk, as well as Dr. Paulinus Noah, Dr. Effiong Ekpenyong and Rev. Fr. Dr. Donatus Udoette, a theologian who is well versed in Greek.[8]

Art

Masks

.jpg.webp)

The masks and accoutrements of the Ekpo society make up the greatest works of art in Ibibio society. Ibibio often purposefully play with proportions in their masks to distort the face.[9] A component that appears often in Ibibio masks is an articulated lower jaw.[9] Ibibio people have an overarching theme of contrasting male and female masks by using dark and light colors respectively. These masks are not always performed together, but there is a general understanding of their opposing relationship. Feminine masks are decorated with light colors such as white. Their features are delicate to emphasize their femininity. On the other hand, masculine masks use dark colors to represent the mystic forces of the forest. These masks often have large features and are created to be intentionally ugly. They achieve this by distorting the features in unnatural manners such as having bulging eyes or misplaced mouths. Many deformities present in the masks come from naturally occurring human diseases and illnesses. One that is often depicted is gangosa - a part of yaws.[10] Signs of baldness and walking sticks also show up often in order to portray symbols of karma and old age. Men's costumes incorporate natural materials from the wilderness such as raffia, and seed pod rattles. Women's costumes use materials such as light colored cloth to represent the order of living in the village.[9]

Ekpo/Ekpe

The masks of this society were used to elicit fear and execute social control.[6] The most common type of mask is one made for the face with waist-length raffia attached. The affect of the masks and their intimidating quality is part of what gives them their power, in addition to the long history of the Ekpo. To put on an Ekpo mask is to surrender earthly identity and assume an ancestral one. Masks used may be ones owned by deceased ancestors, ones made to look like ancestors, or ones made to resemble to village heroes.[6] Many are carved from lightweight wood called ukot (palm wine tree). This makes them easier to wear and move around in. For additional support, the mask is secured to the wearer's head with a rope, and a horizontal piece of wood may be inserted into the mask in order to bite into. In addition to the raffia on the mask itself, performers also wear a knee-length raffia skirt. The lower legs, arms, and hands are painted with charcoal.[6] New raffia is added to the mask each season, and is displayed in the off-season in a family or village shrine.[6]

Ikot Ekpene

The Ibibio are known for their woodcarvings, raffia-weavings, and pottery making.[11] Ikot Ekpene is a town in Nigeria known for its marketplace in which crafts are sold to both tourists and middle-class Nigerians.[11] While the Ibibio are not known for metalworking, there is a significant number of craftspeople making this type of art to be sold.

Most metalwork objects produced have a practical purpose rather than a decorative one. Despite this, Ibibio coffins tend to be highly decorative. They feature ornamental painted metal motifs, colorful plastic sheets, and glass panels on the sides.[11]

Many people who carve Ekpo masks live in Ikot Ekpene.[6]

Body Art

Both temporary and permanent body modifications are used. Rhythm and nature are both considerable motifs at play in the designs.[12] Hairdressing, body painting, and body modification are the main focus of body art performed by the Ibibio. Intentional fattening of young women is another culturally important aspect of the Ibibio.[12]

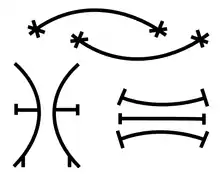

Body painting

In painting, the goal is to emphasize rather than obscure the wearer's face or other parts of the body. The symbol of the dot plays a key role in the understanding of beauty.[12] Okon Umetuk in his article "Body Art in Ibibio Culture", states that

A 'dot' is regarded as the only perfect mark to indicate and summarize beauty in Ibibio culture.[12]

Evidence of this is found in the abundance of dots that appear on the faces and bodies of decorated individuals. An 'X' symbol may be applied to the forehead, wrists, and ankles as a way to mark mediation.[12] When worn by a diviner, it may mark a connection with himself and the gods as well as his people. Members of a ritual may wear it to symbolize peace, humility, as well as acceptance.

Odung is a type of body painting that is used for events such as marriage, childbirth, coming-of-age, and death. It may also be used to show a man's status in the Ekpo society.[12] This process is commonly used among women. It is often done after the birth of a child. The stains that are left afterwards can stay on the skin for up to three months. Professionals are typically the ones who paint others, and the process may take from five to eight hours to complete.[12]

Iduot is another form of body painting which symbolizes fertility. The pigment is taken from crushed camwood and then added to water which produces a red substance. People's palms, feet, legs, and faces are decorated with the pigment. The Ibibio use it partially for its bleaching effect. After continuous usage, it produces a smooth and light skin complexion.[12]

Modern versions of body decoration such as eyeshadow, lipstick, and eyeliner are used by contemporary Ibibio people.[12] These products help them express themselves in conveniently, but are in now way a new form of expression. Body decoration has a long history to the Ibibio. Substances such as the Atido were used for eyelid decoration long before modern eyeshadow.[12] Similar to other cultures around the world, Ibibio women put heavy emphasis on the eye when it comes to make-up.[12]

Mbopo

The fattening of young women in preparation for marriage is an old custom which is dying out. The purpose of this is to enhance the beauty of an unmarried women and prepare her for married life.[12] Once a girl has undergone this ritual, she is considered an Mbopo. This term refers to the process of fattening a girl as well as the girl herself.[12] A key aspect of this is the teaching of future brides the ins and outs of childcare, motherhood, how to keep a home, and how she is expected to behave. The financial situation of a girl's parents determines how long she will stay in the fattening house. This can range anywhere from three months to seven years, but most stay for an average of three years. During their stay, the girls are fed well and not expected to do any labor.[12] This is due to the fact that historically, being overweight was a sign of wealth and good health to the Ibibio.[12]

Nursing mothers also undergo a fattening ritual which usually occurs for only their first child. Both the husband and the mother-in-law are expected to pay for the ritual. The Ibibio consider it natural for a mother to rest following the birth of a child, and therefore the mother performs no strenuous tasks.[12]

Hairstyles

Hair styles are another way for the Ibibio to symbolically mark certain occasions. Styles of hair in Ibibioland include both elaborate braiding with and without the use of thread.[12] Some styles are symbolic of stories or events that have occurred in the wearer's life. If a married woman has unkempt hair, this indicates that someone she is close to, typically her husband, a child, or another relative, has died.[12] Other styles may be indicative of age, marital status, or social standing. There also exists hairstyles without any meaning that are simply worn for fashion purposes.[12]

Ibibio tribes and ethnic groups

The Ibibio are divided into six subcultural groups: Eastern Ibibio, or Ibibio Proper; Western Ibibio, or Annang; Northern Ibibio, or Enyong; Southern Ibibio, or Eket; Delta Ibibio, or Andoni-Ibeno; and Riverine Ibibio, or Efik.[13]

Ibibio numbers

Numbers from zero to ten:[14]

| No. | English | Ibibio |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Zero | Ikpoikpo |

| 1 | One | Keed |

| 2 | Two | Iba |

| 3 | Three | Ita |

| 4 | Four | Inañ |

| 5 | Five | Ition |

| 6 | Six | Itiokeed |

| 7 | Seven | Itiaba |

| 8 | Eight | Itiaita |

| 9 | Nine | Usokeed |

| 10 | Ten | Duop |

Demographics

- Akwa Ibom State of Nigeria

- Cross River State of Nigeria

- Benue Area of Nigeria (Efik-Ibibio people were fourth largest ethnic group of original settlers of Benue of Nigeria)

Ndi Ibibio

Nnyin Ido Ibibio

We are Ibibio people. "Ndi" is an Efik word that means "I am". While "Ndo" is Ibibio just like "Nde" is Annang, it is mostly used by the Efik and Ibibio.

See also

References

- Higman, B. W. (1995). Slave populations of the British Caribbean, 1807-1834 (reprint ed.). The Press, University of the West Indies. p. 450. ISBN 976-640-010-5.

- "Our Story". Indigenous People of Biafra USA. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Essien, Okon E. (1 January 1990). Grammar of the Ibibio Language. University Press Limited. ISBN 9789782491534.

- "Nigerian Arts and Culture Directory - Akwa Ibom State". Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- "Nigerian Arts and Culture Directory - Akwa Ibom State". Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- Akpan, Joseph (Autumn 1994). "Ekpo Society Masks of the Ibibio". African Arts. 27 (4): 48–53. doi:10.2307/3337318. JSTOR 3337318.

- Okon, Gall Patrick (1 January 1984). The Phenomenon of Witch[c]raft Among the Ibibio People of Nigeria. Pontificia Universitas Urbaniana, Facultas Philosophica.

- https://www.newsfrontonline.com.ng/ibibio-bible-is-here/

- Cole, Herbert M., and Dierk Dierking. Invention and Tradition: the Art of Southeastern Nigeria. Prestel, 2012.

- Ebong, Inih (December 1995). "The Aesthetics of Ugliness in Ibibio Dramatic Arts". African Studies Review. 38 (3): 43–59. doi:10.2307/524792. JSTOR 524792.

- Nicklin, Keith (October 1976). "Ibibio Metalwork". African Arts. 10 (1): 20–23. doi:10.2307/3335252. JSTOR 3335252.

- Umetuk, Okon (1985). "Body Art in Ibibio Culture". Nigeria Magazine. 52: 40–56 – via EBSCO.

- Offiong, Daniel A. (1983). "Social Relations and Witch Beliefs among the Ibibio of Nigeria". Journal of Anthropological Research. 39 (1): 81–95. doi:10.1086/jar.39.1.3629817.

- Ñgwed Ikö Anaañ:: Apa Ñgwed 1. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Monday Efiong Noah, Proceedings of the Ibibio Union 1928-1937. Modern Business Press Ltd, Uyo.

- Council of Traditional Rulers, Mbiabong Etim, briefing to Mbiabong Etim Graduates Forum on origin and migration of Mbiabong Etim people of Ini LGA, Akwa Ibom State, 2009.

- Ikpe, Emmanuel Dominic, “Ibibio Nation" 2018. University of Uyo student's Union Government.

- Udo, Edet A. (1983) Who are the Ibibio? Africana-Feb Publishers Limited. Onitsha, Nigeria. ISBN 9781750871

External links

Further reading

- Woman's Mysteries of a Primitive People (published 1915) by D. Amaury Talbot, focuses on the life of women in that culture.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ibibio people. |