Niger Delta

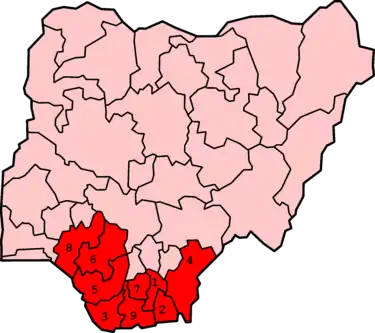

The Niger Delta is the delta of the Niger River sitting directly on the Gulf of Guinea on the Atlantic Ocean in Nigeria.[1] It is typically considered to be located within nine coastal southern Nigerian states, which include: all six states from the South South geopolitical zone, one state (Ondo) from South West geopolitical zone and two states (Abia and Imo) from South East geopolitical zone. Of all the states that the region covers, only Cross River is not an oil-producing state.

The Niger Delta is a very densely populated region sometimes called the Oil Rivers because it was once a major producer of palm oil. The area was the British Oil Rivers Protectorate from 1885 until 1893, when it was expanded and became the Niger Coast Protectorate. The delta is a petroleum-rich region and has been the center of international controversy over pollution.

Geography

The Niger Delta, as now defined officially by the Nigerian government, extends over about 70,000 km2 (27,000 sq mi) and makes up 7.5% of Nigeria's land mass. Historically and cartographically, it consists of present-day Bayelsa, Delta, and Rivers States. In 2000, however, Obasanjo's regime included Abia, Akwa-Ibom, Cross River State, Edo, Imo and Ondo States in the region.

The Niger Delta, and the South South geopolitical zone (which contains six of the states in Niger Delta) are two different entities. The Niger Delta separates the Bight of Benin from the Bight of Bonny within the larger Gulf of Guinea.

Demographics

Some 31 million people[2] of more than 40 ethnic groups including the Bini, Itsekiri, Efik, Esan, Ibibio, Annang, Yoruba, Oron, Ijaw, Igbo, Ikwerre, Abua/Odual, Isoko, Urhobo, Ukwuani, Kalabari, Okrika, Ogoni, Epie-Atissa people and Obolo people, are among the inhabitants of the political Niger Delta, speaking about 250 different dialects.

Language groups spoken in the Niger Delta include the Ijaw languages, Itsekiri language and Central Delta languages. Edoid languages and Ika languages are also spoken in peripheral areas.[3]

History

Colonial period

The area was the British Oil Rivers Protectorate from 1885 until 1893, when it was expanded and became the Niger Coast Protectorate. The core Niger Delta later became a part of the eastern region of Nigeria, which came into being in 1951 (one of the three regions, and later one of the four regions). The majority of the people were those from the colonial Calabar, Itsekiri and Ogoja divisions, the present-day Ogoja, Itsekiri, Annang, Ibibio, Oron, Efik, Ijaw and Ogoni peoples. The National Council of Nigeria and Cameroon (NCNC) was the ruling political party of the region. The NCNC later became the National Convention of Nigerian Citizens, after western Cameroon decided to separate from Nigeria. The ruling party of eastern Nigeria did not seek to preclude the separation and even encouraged it. The then Eastern Region had the third, fourth and fifth largest indigenous ethnic groups in the country including Igbo, Efik-Ibibio and Ijaw.

In 1953, the old eastern region had a major crisis due to the expulsion of professor Eyo Ita from office by the majority Igbo tribe of the old eastern region. Ita, an Efik man from Calabar, was one of the pioneer nationalists for Nigerian independence. The minorities in the region, the Ibibio, Annang, Efik, Ijaw and Ogoja, were situated along the southeastern coast and in the delta region and demanded a state of their own, the Calabar-Ogoja-Rivers (COR) state. The struggle for the creation of the COR state continued and was a major issue concerning the status of minorities in Nigeria during debates in Europe on Nigerian independence. As a result of this crisis, Professor Eyo Ita left the NCNC to form a new political party called the National Independence Party (NIP) which was one of the five Nigerian political parties represented at the conferences on Nigerian Constitution and Independence.

Post-colonial period

In 1961, another major crisis occurred when the then eastern region of Nigeria allowed present-day Southwestern Cameroon to separate from Nigeria (from the region of what is now Akwa Ibom and Cross River states) through a plebiscite while the leadership of the then Northern Region took the necessary steps to keep Northwestern Cameroon in Nigeria, in present-day Adamawa and Taraba states. The aftermath of the 1961 plebiscite has led to a dispute between Cameroon and Nigeria over the small territory of Bakassi.

A new phase of the struggle saw the declaration of an Independent Niger Delta Republic by Isaac Adaka Boro during Nigerian president Ironsi's administration, just before the Nigerian Civil War.

Also just before the Nigerian civil war, Southeastern State of Nigeria was created (also known as Southeastern Nigeria or Coastal Southeastern Nigeria), which had the colonial Calabar division, and colonial Ogoja division. Rivers State was also created. Southeastern state and River state became two states for the minorities of the old eastern region, and the majority Igbo of the old eastern region had a state called East Central state. Southeastern state was renamed Cross River state and was later split into Cross River state and Akwa Ibom state. Rivers state was later divided into Rivers state and Bayelsa State.

Nigerian Civil War

The people of the eastern region suffered heavily and sustained many deaths during 1967–1970 Nigerian Civil War, also known as the Biafran War, in which the eastern region declared an independent state named Biafra that was eventually defeated, thereby preserving the sovereignty and indivisibility of the Nigerian state, which led to the loss of many souls.[4][5][6]

Non-violent resistance

During the next phase of resistance in the Niger Delta, local communities demanded environmental and social justice from the federal government, with Ken Saro Wiwa and the Ogoni tribe as the lead figures for this phase of the struggle. Cohesive oil protests became most pronounced in 1990 with the publication of the Ogoni Bill of Rights. The indigents protested against the lack of economic development, e.g. schools, good roads, and hospitals, in the region, despite all the oil wealth created. They also complained about environmental pollution and destruction of their land and rivers by foreign oil companies. Ken Saro Wiwa and nine other oil activists from Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) were arrest and killed under Sani Abacha in 1995. Although protests have never been as strong as they were under Saro-Wiwa, there is still an oil reform movement based on peaceful protests today as the Ogoni struggle served as a modern-day eye opener to the Peoples of the region.[7]

Recent armed conflict

Unfortunately, the struggle got out of control, and the present phase has become militant. When long-held concerns about loss of control over resources to the oil companies were voiced by the Ijaw people in the Kaiama Declaration in 1998, the Nigerian government sent troops to occupy the Bayelsa and Delta states. Soldiers opened fire with rifles, machine guns, and tear gas, killing at least three protesters and arresting twenty-five more.[8]

Since then, local indigenous activity against commercial oil refineries and pipelines in the region have increased in frequency and militancy. Recently foreign employees of Shell, the primary corporation operating in the region, were taken hostage by outraged local people. Such activities have also resulted in greater governmental intervention in the area, and the mobilization of the Nigerian army and State Security Service into the region, resulting in violence and human rights abuses.

In April 2006, a bomb exploded near an oil refinery in the Niger Delta region, a warning against Chinese expansion in the region. MEND stated: "We wish to warn the Chinese government and its oil companies to steer well clear of the Niger Delta. The Chinese government, by investing in stolen crude, places its citizens in our line of fire."[9]

Government and private initiatives to develop the Niger Delta region have been introduced recently. These include the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC), a government initiative, and the Development Initiative (DEVIN), a community development non-governmental organization (NGO) based in Port Harcourt in the Niger Delta. Uz and Uz Transnational, a company with a strong commitment to the Niger Delta, has introduced ways of developing the poor in the Niger Delta, especially in Rivers State.

In September 2008, MEND released a statement proclaiming that their militants had launched an "oil war" throughout the Niger Delta against both, pipelines and oil-production facilities, and the Nigerian soldiers that protect them. Both MEND and the Nigerian Government claim to have inflicted heavy casualties on one another.[10] In August 2009, the Nigerian government granted amnesty to the militants; many militants subsequently surrendered their weapons in exchange for a presidential pardon, rehabilitation programme, and education.

Sub-regions

Western Niger Delta

Western Niger Delta consists of the western section of coastal South-South Nigeria which includes Delta, and the southernmost parts of Edo, and Ondo States. The western (or Northern) Niger Delta is an heterogeneous society with several ethnic groups including the Itsekiri, Urhobo, Isoko, Ijaw (or Izon) and Ukwuani groups in Delta State; the Bini, Esan,Auchi,Esako,oral,igara and Afenmai in Edo State; and the Yoruba (Ilaje) in Ondo State. Their livelihoods are primarily based on fishing and farming. History has it that the Western Niger was controlled by chiefs of the four primary ethnic groups the Itsekiri, Isoko, Ijaw, and Urhobo with whom the British government had to sign separate "Treaties of Protection" in their formation of "Protectorates" that later became southern Nigeria.

Central Niger Delta

Central Niger Delta consists of the central section of coastal South-South Nigeria which includes Bayelsa, Rivers, Abia and Imo States. The Central Niger Delta region has the Ijaw (including the Nembe-Brass, Ogbia, Kalabari people, Ibani of Opobo & Bonny, Abua, Okrika, Engenni and Andoni clans), the Ogoni People (Khana, Gokana, Tai and Eleme) and the Etche, Ogba, Ikwerre, Ndoni, Ekpeye and Ndoki in Rivers State and the Igbo tribe in Abia State and Imo State, Nigeria

Eastern Niger Delta

Eastern Niger Delta consists of Cross River State and Akwa Ibom State.

Nigerian oil

Nigeria has become West Africa's biggest producer of petroleum. Some 2 million barrels (320,000 m3) a day are extracted in the Niger Delta. It is estimated that 38 billion barrels of crude oil still reside under the delta as of early 2012.[11] The first oil operations in the region began in the 1950s and were undertaken by multinational corporations, which provided Nigeria with necessary technological and financial resources to extract oil.[12] Since 1975, the region has accounted for more than 75% of Nigeria's export earnings.[13] Together oil and natural gas extraction comprise "97 per cent of Nigeria's foreign exchange revenues".[14] Much of the natural gas extracted in oil wells in the Delta is immediately burned, or flared, into the air at a rate of approximately 70 million m³per day. This is equivalent to 41% of African natural gas consumption and forms the largest single source of greenhouse gas emissions on the planet. In 2003, about 99% of excess gas was flared in the Niger Delta,[15] although this value has fallen to 11% in 2010.[16] (See also gas flaring volumes). The biggest gas flaring company is the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Ltd, a joint venture that is majority owned by the Nigerian government. In Nigeria, "...despite regulations introduced 20 years ago to outlaw the practice, most associated gas is flared, causing local pollution and contributing to climate change."[17] The environmental devastation associated with the industry and the lack of distribution of oil wealth have been the source and/or key aggravating factors of numerous environmental movements and inter-ethnic conflicts in the region, including recent guerrilla activity by the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND).

In September 2012 Eland Oil & Gas purchased a 45% interest in OML 40, with its partner Starcrest Energy Nigeria Limited, from the Shell Group. They intend to recommission the existing infrastructure and restart existing wells to re-commence production at an initial gross rate of 2,500 barrels (400 m3) of oil per day with a target to grow gross production to 50,000 barrels (7,900 m3) of oil per day within four years.

Oil revenue derivation

Oil revenue allocation has been the subject of much contention well before Nigeria gained its independence. Allocations have varied from as much as 50%, owing to the First Republic's high degree of regional autonomy, and as low as 10% during the military dictatorships. This is the table below.

| Year | Federal | State* | Local | Special Projects | Derivation Formula** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958 | 40% | 60% | 0% | 0% | 50% |

| 1968 | 80% | 20% | 0% | 0% | 10% |

| 1977 | 75% | 22% | 3% | 0% | 10% |

| 1982 | 55% | 32.5% | 10% | 2.5% | 10% |

| 1989 | 50% | 24% | 15% | 11% | 10% |

| 1995 | 48.5% | 24% | 20% | 7.5% | 13% |

| 2001 | 48.5% | 24% | 20% | 7.5% | 13% |

* State allocations are based on 5 criteria: equality (equal shares per state), population, social development, land mass, and revenue generation.

**The derivation formula refers to the percentage of the revenue oil-producing states retain from taxes on oil and other natural resources produced in the state. World Bank Report

Media

The documentary film Sweet Crude, which premiered April 2009 at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival, tells the story of Nigeria's Niger Delta.

Environmental issues

The effects of oil in the fragile Niger Delta communities and environment have been enormous. Local indigenous people have seen little if any improvement in their standard of living while suffering serious damage to their natural environment. According to Nigerian federal government figures, there were more than 7,000 oil spills between 1970 and 2000.[18] It has been estimated that a clean-up of the region, including full restoration of swamps, creeks, fishing grounds and mangroves, could take 25 years.[19]

See also

References

- C. Michael Hogan, "Niger River", in M. McGinley (ed.), Encyclopedia of Earth Archived 2013-04-20 at the Wayback Machine, Washington, DC: National Council for Science and Environment, 2013.

- CRS Report for Congress, Nigeria: Current Issues. Updated 30 January 2008.

- Blench, Roger (2019). An Atlas of Nigerian Languages (4th ed.). Cambridge: Kay Williamson Educational Foundation.

- "Chronology of Important Events in the Nigerian Civil War", The International Politics of the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970, Princeton University Press, 2015-12-31, pp. xv–xx, doi:10.1515/9781400871285-003, ISBN 978-1-4008-7128-5

- Heerten, Lasse; Moses, A. Dirk (2017-07-06), "The Nigeria-Biafra War", Postcolonial Conflict and the Question of Genocide, Routledge, pp. 3–43, doi:10.4324/9781315229294-1, ISBN 978-1-315-22929-4

- Ekwe-Ekwe, Herbert. (1991). The Biafra War : Nigeria and the aftermath. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-88946-235-6. OCLC 476261625.

- Strutton, Laine (2015). The New Mobilization from Below: Women's Oil Protests in the Niger Delta, Nigeria (Ph.D.). New York University.

- "State of Emergency Declared in the Niger Delta". Human Rights Watch. 1998-12-30. Archived from the original on 2012-08-05. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- Ian Taylor, "China's environmental footprint in Africa" Archived 2007-02-23 at the Wayback Machine, China Dialogue, 2 February 2007.

- "Nigeria militants warn of oil war" Archived 2008-09-15 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 14 September 2008.

- Isumonah, V. Adelfemi (2013). "Armed Society in the Niger Delta". Armed Forces & Society. 39 (2): 331–358. doi:10.1177/0095327x12446925. S2CID 110566551.

- Pearson, Scott R. (1970). Petroleum and the Nigerian Economy. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-8047-0749-9.

- Akpeninor, James Ohwofasa (2012-08-28). Giant in the Sun: Echoes of Looming Revolution?. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4772-1868-6.

- Nigeria: Petroleum Pollution and Poverty in the Niger Delta. United Kingdom: Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat, 2009, p. 10.

- "Nigeria's First National Communication Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change" (PDF). UNFCC. Nov 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- Global Gas Flaring reduction, The World Bank Archived 2012-03-01 at the Wayback Machine, "Estimated Flared Volumes from Satellite Data, 2006–2010."

- "Gas Flaring in Nigeria" (PDF). Friends of the Earth. October 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- John Vidal, "Nigeria's agony dwarfs the Gulf oil spill. The US and Europe ignore it" Archived 2016-12-15 at the Wayback Machine, The Observer, 30 May 2010.

- Vidal, John (1 June 2016). "Niger delta oil spill clean-up launched – but could take quarter of a century". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

Sources

- Niger Delta-Archive of News, Interviews, Articles, Analysis from 1999 to Present

- Proceedings of the Ibibio Union 1928–1937. Edited by Monday Efiong Noah. Modern Business Press Ltd, Uyo.

- Urhobo Historical Society (4 August 2003). Urhobo Historical Society Responds to Itsekiri Claims on Wari City and Western Niger Delta.

- "Nigeria's agony dwarfs the Gulf oil spill. The US and Europe ignore it"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Niger Delta. |

- National Geographic Magazine: "Curse of the Black Gold, Hope, and betrayal on the Niger Delta" — February 2007 issue.

- Nigerdeltaforum.com: forum on the Niger Delta and its people

- Niger-Delta Development Commission, Niger Delta: A Brief History

- American Association for the Advancement of Science, Niger Delta

- Environmental Rights Action

- News on the Niger Delta