Icarians

The Icarians /ɪˈkɛriənz/ were a French-based utopian socialist movement, established by the followers of politician, journalist, and author Étienne Cabet. In an attempt to put his economic and social theories into practice, Cabet led his followers to the United States of America in 1848, where the Icarians established a series of egalitarian communes in the states of Texas, Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, and California. The movement split several times due to factional disagreements.

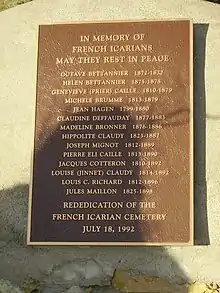

The last community of Icarians, located a few miles outside Corning, Iowa, disbanded voluntarily in 1898. The 46 years of tenure at this location made the Corning Icarian Colony one of the longest-lived non-religious communal living experiments in US history.[1]

History

Cabet as radical French politician

.jpg.webp)

Étienne Cabet was born in Dijon, France in 1788 to a middle-class family of artisans.[2] Cabet attended a Roman Catholic secondary school and continued his education, ultimately earning a Doctorate of Law degree in 1812.[2] Cabet was not inclined towards jurisprudence, however, preferring the rough and tumble of politics and journalism. Following the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1815, Cabet became active in the struggle against conservative theocratic monarchism, participating in political groups which espoused a constitutional and republican form of government under monarchical leadership.[2]

In 1820 Cabet moved to Paris, the political center of the French nation.[2] There he continued to participate in secret revolutionary societies, at considerable personal risk.[3] It ultimately took a decade for this underground political effort to bear fruit when in July 1830 revolution erupted seeking the fundamental change of the conservative regime which had gained power in the Bourbon Restoration following the fall of Napoleon.

This Revolution of 1830 in a matter of a few frenzied days forced the abdication of the conservative monarch Charles X and returned constitutional government to France. Cabet played a leading role in the revolution as a leading member of the so-called "Insurrection Committee," activity for which he was recognized with appointment as Attorney-General for Corsica following the coronation of Louis Philippe as king.[3]

Historian Morris Hillquit has argued that the posting of Cabet to Corsica was a calculated "shrewd move on the part of the government" to remove a prominent radical critic from the political hothouse of Paris "under the guise of a reward for his services during the revolution."[3] Be that as it may, despite his employment as a government functionary in Corsica, Cabet moved into criticism of the new Orléanist regime for its conservatism and half-measures with respect to constitutional rule and the democratic rights of the people. This brought about Cabet's prompt removal from office by the new regime in Paris, at whose pleasure Cabet served.[3] Following his dismissal as Corsican Attorney-General, Cabet turned his hand to writing, authoring a four-volume history of the French Revolution. He also remained active in politics and was elected as a deputy to the lower chamber of the National Assembly in 1834.[4] Cabet emerged as a fierce opponent of the new conservative regime and a potential revolutionary leader, drawing the attention of the regime and its repressive mechanism.[4] In an effort to eliminate the dangerous democratic agitator, Cabet was given the choice of two years' imprisonment or five years in foreign exile.[5] He decided upon the latter punishment and immediately went into exile in England.[6]

During his five years of English exile, Cabet dedicated himself to philosophical and economic study, carefully considering the relationship between political structures and economic welfare throughout history.[7] Cabet's findings were later summarized thus by one of his acolytes:

Studying, pondering the history of all ages and countries, he at length arrived at the conclusion that mere political reforms are powerless to give to society the ... welfare which it obstinately seeks. ... He found at all epochs the same phenomena: society sundered in twain; on one side a minority, cruel, idle, arrogant, usurping exclusive enjoyment of the products of a majority, passive, toiling, ignorant, who remained wholly destitute. ... To change all this, to find the means of preventing one portion of humanity from being eternally the prey of the other — such was his desire, the goal of all his efforts.[8]

Cabet turned to the idea of reorganization of society on a communal basis — known as "Communism" in the terminology of the day. His ideas for the modification of society closely paralleled those of a man he met in English exile, Robert Owen.[9]

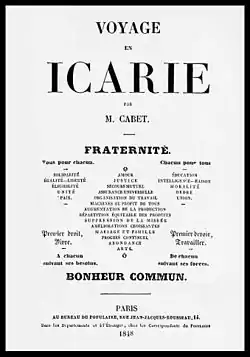

Voyage en Icarie

In 1839, his five years' exile in England completed, Cabet returned to his native France. Upon his return he began writing a book to expound his economic and social ideas, following the example of Thomas More and using the form of an allegorical novel which allowed not only the exposition of the ideal form of administration but an opportunity for cloaked criticism of the existing regime.[9]

The result of Cabet's writing was published in 1840 as Voyage en Icarie (Voyage to Icaria). A rough translation by Cabet was serialized in Icarian periodicals of the 1850s; an additional translation by academic specialist Robert Sutton has been deposited with the Library of Congress, although it remains unpublished.[11] a basic plot outline was published by Morris Hillquit in 1903:

Lord Carisdall, a young English nobleman, has by chance learned of the existence of a remote and isolated country known as Icaria. The unusual mode of life, habits, and form of government of the Icarians excite his lordship's curiosity, and he decides to visit their country. Voyage en Icarie purports to be a journal in which our traveler records his remarkable experiences and discoveries in the strange country.

The first part of the book contains a glowing account of the blessings of the cooperative system of industry of the Icarians, their varied occupations and accomplishments, comfortable mode of life, admirable system of education, high morality, political freedom, equality of sexes, and general happiness. The second part contains a history of Icaria. It appears that the social order of the country had been similar to that prevailing in the rest of the world, until 1782, when the great national hero, Icar, after a successful revolution, established the system of communism.

This recital gives Cabet the opportunity for a scathing criticism of the faults of the present social structure, and also to outline his favorite measures for the transition from that system to the new regime.

... The last part of the book is devoted to the history of development of the idea of communism, and contains a summary of the views of almost all known writers on the subject, from Plato down to the famous utopians of the early part of the 19th Century.[12]

Although regarded today as a "plodding melodrama"[13] in which the reader was inundated with "tedious details of incidental aspects of Icarian life,"[14] Cabet's book was well received by readers of his day, with the principles it outlined viewed by many as a blueprint for advancement from a disappointing present to a glorious future.[15] Multiple editions of the book followed in quick succession and with public interest awakened Cabet quickly made the transition from author to builder of a practical movement to advance the communal ideas which he had expounded.[15] In March 1841 Cabet launched a monthly magazine, Le Populaire, as well as an annual Icarian Almanac to help propagandize and organize the new political movement's supporters.[15]

So-called "Icarianism" attracted numerous supporters in such French cities as Reims, Leon, Nantes, Toulouse, and Toulon, with Cabet claiming the existence of 50,000 adherents of his ideas by the end of 1843.[16] These supporters began to see Cabet as a political messiah and sought to implement the leader's ideas in a practical setting.[16] It was gradually decided in this period that France did not present a favorable economic, political, or social environment for the implementation of the Icarian ideas; instead, the United States of America was chosen as a more fitting site for colonization – a nation with vast expanses of relatively inexpensive land and a democratic political tradition.[16]

In May 1847, Cabet's organ Le Populaire carried a lengthy article entitled "Allons en Icarie" (Let Us Go to Icaria), detailing the proposal to establish an American colony based upon the Icarian political and economic ideals and calling for those committed to building an artisanal and agrarian community to volunteer.[16] The wheels were thus set in motion for the formation of what was intended to be a prosperous and enviable collective entity.

Colonization begins

Cabet believed that at least 10,000 or 20,000 working men would immediately enlist in the American colonization scheme, with the number soon swelling to a million skilled workers and artisans.[17] Towns and huge cities bursting with industry would shortly follow, with accompanying schools and cultural facilities assuring the good life for a happy and fulfilled community.[17] Announcement of the plan was met with enthusiasm, and offers of participation along with gifts of money, seeds, farm implements, clothing, books, and other valuable and useful items began to flow in.[17]

Cabet gave himself the task of choosing a precise location for colonization. Cabet turned to his friend Robert Owen for advice, traveling to London in September 1847 to consult with his British co-thinker.[17] Owen recommended colonization in the new American state of Texas, a location reckoned to possess vast tracts of unoccupied land which would be as inexpensive as it was plentiful.[16] Cabet made contact with a Texas land agent, The Peters Company, which agreed to present to Owen title for 1 million acres of land so long as it was colonized by July 1, 1848.[18]

Icarian settlements

Denton County, Texas

On February 3, 1848 a so-called "advance guard" of 69 Icarians departed from Le Havre, France for a new life in Texas, leaving aboard the sailing ship Rome.[18] These were to proceed to the port of New Orleans and to make their way from there to the designated area in Texas, which was represented as being in close proximity to the Red River.[20] The advance guard arrived in America on March 27, 1848.[18]

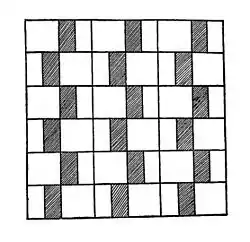

They were quick to discover that they had been deceived and that the actual lands designated for colonization were fully 25 miles away from the Red River; moreover, colony lands were not contiguous, but rather were separated into a checkerboard fashion,[21] alternating state and private lands, making integrated communal life not possible.[20] Moreover, instead of the promised 1 million acres, actual contractual terms of the land distribution provided for the distribution of 320 acres of land to 3,125 individuals or families who each had to construct a log cabin and occupy their allotment by the deadline date of July 1, 1848.[20] With only 69 hands available for the construction, there was little hope for construction of more than about 30 cabins by the deadline.[22] The promised 1 million acres was thereby transformed into perhaps 10,000. By 1849, only 281 Icarians stayed loyal to Cabet and remained to rebuild, whereas the rest went back to France.[21]

The party could only proceed by boat to Shreveport. A wagon was obtained and loaded it with provisions for a difficult overland trek via the Bonham Trail to a resting place halfway to the final destination. The first group of 25 men departed on April 8, followed in a second wagon by 14 others shortly thereafter.[23] Both wagons broke down en route and the 39 Icarians were forced to proceed in small groups, packing what they could on their backs. It was not until April 21 that they arrived at their resting place, still more than a hundred difficult miles from their goal.[24]

Only 27 intrepid French settlers were able to make the final leg of the trip from the farm designated as a resting place to their new Texan utopia, a site located in today's Denton County in Texas (northwest of Dallas).[24] The small group arrived June 2, 1848,[24] and immediately began a frenzied effort to construct dwellings in order to stake their land claims, attempting at the same time to plow and farm the prairie.[22] Virtually no time remained to meet the terms of the land concession. The hot summer sun began to bake the ground. Poorly fed, poorly housed, overworked and exhausted, the Icarian colonists next fell victim to an outbreaks of cholera and malaria, illnesses which killed four and sickened the rest.[25] Making a bad situation still worse, the one medical doctor in the company broke down into a state of insanity and deserted his fellows.[24]

Back home in France, the Revolution of 1848 had long been in full swing and King Louis Philippe overthrown. The necessity of emigration to achieve democratic reforms seemed less compelling and the volunteers for Icarian colonization in America melted away.[25] Some 1500 settlers were planned for the next wave of settlers; only 19 made the trip, of whom barely more than half ever made it to Texas to join the beleaguered "advance guard" in their Sisyphean task.[25]

The grim reality of their situation now clear, the Texas colonization venture was written off as a total loss by the participants and the survivors divided into small groups to make their way back to Shreveport and from there to New Orleans.[25] Four more died en route.[24] Finally arriving in New Orleans late in 1848, the Texas pioneers were met by several hundred colonization enthusiasts from France, who had been slowly congregating in that city.[25] Their mood was grim.

News of the Texas catastrophe reached Cabet in France and on December 13, 1848, he set out from Liverpool for America in an attempt to shore up the project.[26] After landing in New York, he shipped out again for New Orleans, disembarking there on January 19, 1849.[27] Cabet found his supporters in disarray, "in the deplorable spirit of a defeated army," to borrow words from an official history by the group.[26] A portion of the prospective colonists sought to abandon the project and to return to France; others sought to continue the colonization project in a more suitable locale.[26]

On January 21 the colonists held a general meeting to decide their fate. Cabet declared that if a majority sought to return home to France, he would support the decision — although with all the costs absorbed in the previous year such a move would have meant financial disaster for all.[28] A small majority of 280 decided to continue with the colonization project if a more suitable locale was found; 200 sought to return.[28] A formal split of the Icarians along these lines immediately followed, the first of three great factional rifts which would split the movement.

An amount of money was pared from the treasury to send the 200 disaffected Icarians home to Le Havre.[lower-alpha 1] Once back in France, many of the former Icarian colonists initiated legal proceedings against Cabet for fraud – charges which he was ultimately forced home to answer.[28]

The majority, consisting of about 280 people, joined Cabet in setting out for the Mississippi River town of Nauvoo, located in Hancock County, Illinois, where the Icarian experiment finally began in earnest.[29]

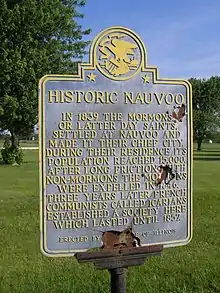

Nauvoo, Illinois

Nauvoo was founded in 1839 for the gathering of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Even though Joseph Smith, the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, was killed in 1844, by 1845 Nauvoo had grown to a community of about 15,000 people – dwarfing the city of Chicago, which had only about 8,000 inhabitants at that time.[29] Under threat of continuing violence from the surrounding communities and following a succession crisis, most of the Latter-day Saints, under Brigham Young left in 1846 for Salt Lake City, Utah, the current headquarters of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Latter-day Saints later sold their land to the Icarians in 1849.[30]

Nauvoo would become the first permanent Icarian Community, the Icarians immediately adopting the charter and structure described in Cabet's Voyage en Icarie. The structure included an annually elected president and one officer each to administrate finance, farming, industry, and education.[30] New members were admitted by a majority approval vote by the adult males, after living in the commune for four months, forfeiting all personal property, and pledging $80.[30] Nonetheless, visitors were welcome to stay as long as they wished in a hotel.[31]

Every family used the same amount of space (two rooms in an apartment building), and were allowed the same amount of furniture.[30] After the age of four, children lived apart from their parents at a boarding school, and visited families only on Sundays. This was done to foster a love for the community "without developing special affection for parents" from a young age,[31] theoretically instrumental to the smooth working of a Utopian society. Sundays were not what would be a typical religious Sunday; the Icarians practiced no religion,[31] but there were days people voluntarily gathered in a fellowship called "Cours icarien" to discuss Cabet's writings and Christian morals and ethics.[31]

Because long-term celibacy was viewed askance by the community, marriage was the norm. Divorce was acceptable under the assumption individuals would remarry soon.[31]

With the basic need of shelter immediately settled, a short period of energetic growth and relative prosperity followed. Farmland was rented, a saw mill and flour mill opened, workshops established, and schools and a theater founded.[32] A periodical press was launched, publishing in French, English, and German, and an office was established in Paris to recruit adherents for the American colony.[32] The Nauvoo cultural life thrived. The Icarians held regular band concerts and theatre productions. Their library consisted of an extensive collection, ranging from reference works to applied science to popular novels, all in English and French, and totaling over 4,000 volumes.[31] By 1855 there would be more than 500 participants in the Icarian project.[26]

Political disagreements and personal animosities would lead to the second major split of the Icarians in America. Étienne Cabet began in America in 1849 with the authority of the sect's unquestioned leader, status which was freely granted to him by those inspired to action by the man's writings.[32] This individual status as supreme decision-maker stood in marked contradiction to the democratic ideals of the community, however. Cabet himself realized as much and in 1850 he proposed a constitution which provided for an elected President and an elected board of directors, which would supplant the absolute, personal authority of the unitary leader.[32] This system functioned effectively for a time.

In 1852, a lawsuit was filed in Paris against Cabet by a number of dissident former Icarians, who claimed their property was obtained by him by means of fraud. Cabet returned to France for 18 months to fight these charges. When he returned to America, Cabet began to push through a series of restrictive rules, including the prohibition of talking in workshops, banning the use of tobacco or alcohol, and other regulations which were unpopular with some members of the community. He also moved to reestablish his own personal decision-making authority over the entire community, proposing in December 1855 to revise the constitution to provide for a powerful President elected to a four-year term.[32] This President, under Cabet's new scheme, would have the ability to control all aspects of the community's government.[32]

_P6081245.jpg.webp)

This position by Cabet was anathema to a majority of the Icarian cooperators, who were deeply inspired and influenced by the history and traditions of the Great French Revolution and its democratic ideals. Cabet's position was deeply held by him as essential to the preservation of the community's moral fiber, however, and in his position he was staunchly supported by "a strong minority."[32]

The factional battle continued for a year between the Dissidents, led by Alexis Armel Marchand and Jean Baptist Gerard,[33] and the Cabetists, finally resolving itself in a formal split.[32] The Cabetists were expelled, and Cabet led about 170 of his followers out of Nauvoo in October 1856, heading downstream along the Mississippi to the bustling metropolis of St. Louis to establish a new colony in that vicinity.

Shattered by the loss of about 40% of its members and no longer able to raise financial support in France, the Nauvoo colony of the majority faction ultimately encountered financial difficulties and was forced to disband in 1860. Many of the participants of the defunct Nauvoo colony would join the parallel Icarian colony in Iowa.

One legacy still continues in Nauvoo. Emile and Annette Baxte joined the Icarians in 1855 and then left in 1857 and founded Baxter's Vineyards and Winery. It has been operated by several generations of the family and is Illinois' oldest winery.[34][35]

Cheltenham, Missouri

The Icarians who had left Nauvoo owing to their support of personal leadership of Cabet and his restrictive behavioral agenda arrived in St. Louis on November 6, 1856. In an ironic twist of fate, the leader for whom they had executed the split of Icaria in Nauvoo, Étienne Cabet, died just two days later. The new leader became a thirty-two-year-old lawyer named Benjamin Mercadier.[33]

On February 15, 1858, a group of 151 Icarians took possession of a few hundred acres in Cheltenham, St. Louis, Missouri. These Cabetists used Cabet's money and put down $500 on a $25,000 mortgage for thirty-nine acres and three buildings southwest of this city.[33] Adjusting to a new area and new locals was difficult, but the Icarians adopted a constitution, a replica of the Nauvoo one, worked in the city, and enrolled their children into the local public schools.[33] The colony quickly fell into various arguments. During the Civil War, many young men joined the Union cause. By 1864, only about twenty residents remained on the property. For the rest of the people, epidemics of dysentery and cholera occurred in the warmer months.[33] Because the Icarians could not meet the mortgage payments, in March 1864, Arsène Sauva returned the keys to the property to St. Louis banker Thomas Allen (from whom the property had been purchased in 1858), leaving a large debt. That same year, most members left the community, and the Cheltenham Icaria was no longer extant.[33]

In 1872, the buildings went into a state of disrepair, and in 1875, a fire destroyed the buildings on this property, removing the last evidence of the Icarian colony.

Corning, Iowa

In 1852, Icarians purchased land in Adams County, Iowa to form a new permanent settlement, and Icarians began settling southwest of Queen City in 1853. In 1860, when the Nauvoo colony went bankrupt, many members of the community moved to the new site in Iowa. The settlers arrived with nothing but their skills along with $20,000 of debt. Their land was that of 4,000 acres (16 km2) where they first found shelter in mud hovels and then in crudely built log cabins. The colony near what became Corning, Iowa was granted a charter of incorporation by the state of Iowa in 1860. The community prospered during the Civil War by selling food at good prices, and they were able to pay their collective debt by 1870.

In the spring of 1874 the Icarian colony near Corning was visited by Charles Nordhoff, who was travelling the United States doing investigative research on such communities in preparation for writing a book.[36] At that time Nordhoff found a two-story building, 60 feet by 24, which served as a collective dining hall, washhouse, and school[36] About a dozen cheaply built frame houses sheltered the colonists, who at the time included about 65 members in 11 families.[37] Most of those in the community were of French ethnicity, and French was the language spoken by the colonists, although among their number were included "one American, one Swiss, a Swede, a Spaniard, and two Germans."[36]

Nordhoff wrote:

The children look remarkably healthy, and on Sunday were dressed with great taste. The living is still of the plainest. In the common dining-hall they assemble in groups at the tables, which were without a cloth, and they drink out of tin cups, and pour their water from tin cans. 'It is very plain,' said one to me; 'but we are independent — no man's servants — and we are content.'[36]

Nordhoff noted that the Iowa colony sold to the market about 2,500 pounds of wool annually, as well as cattle and hogs and the product of its manufacturing facilities.[36] The group continued to operate under an elaborate constitution written by Cabet, "which lays down with great care the equality and brotherhood of mankind, and the duty of holding all things in common; abolishes servitude or service (or servants); commands marriage, under penalties; provides for education; and requires that the majority shall rule."[38] Governance was based upon weekly meetings of all adults each Saturday, with a President elected annually as formal head of the colony but officers for the conduct of meetings elected each week.[39] In addition to the President there were four elected directors, in charge of agriculture, clothing, industry, and construction, respectively.[39]

Nordhoff noted that the community had no formal religious observances.[39] Instead, "Sunday is a day of rest from labor, when the young men go out with guns, and the society sometimes has theatrical representations, or music, or some kind of amusement. The principle is to let each one do as he pleases."[39]

In the 1870s, the Icarian colony near Corning had another split. The "vieux icariens" were against allowing women the right to vote, but the "jeunes icariens" were in favor. By a vote of 31–17, the entire community voted against the franchise for women. After that, the jeunes icariens moved to a new site on the same property about one mile southeast. The move was done by moving eight frame houses from the original colony.[40] The vieux icariens community was no longer viable and was forced to disband due to bankruptcy in 1878. The new community established a new constitution in 1879.[41]

In 1898, this last community of Icarians disbanded voluntarily; the members chose to integrate into the surrounding towns.[1] Its 46 years in existence made the Corning Icarian community the longest-lived non-religious communal living experiment in American history.[1]

A historical exhibit about the Icarians can be found in the lobby of the Adams County hall in Corning, and a living history site is being rebuilt on the location of the site where the Icarians lived until 1898.[42]

| Icarians | |

|---|---|

California Registered Historical Landmark No. 981: Icaria-Speranza Utopian Colony | |

| Location | Sonoma County |

| Official name | Icaria-Sperenza Commune[43] |

| Designated | November 22, 1988 |

| Reference no. | 835 |

Cloverdale, California

A new colony of "Icaria Speranza" was established by Jules Leroux (brother of French socialist philosopher Pierre Leroux) and Armand Dehay, who in 1881 moved from Jeune Icarie to an area just south of Cloverdale, California. The group bought the 885-acre Bluxome ranch on the Russian River, which included vineyards, orchards, and arable land.[44] Originally named Speranza, after Leroux's review L'Esperance, the community gained remaining members of Young Icaria and became Icaria-Speranza.[45] At its height, the settlement had an estimated population of 55 individuals.[46] This settlement disbanded in 1886. Today there is an historical marker just south of town marking where their schoolhouse was.[47]

Community structure

Admissions

A charter created by the Society in 1853 specified that residents of the Nauvoo colony were required to donate all their worldly goods to the community, which had to include a minimum of $60. Those who passed a probationary period of four months would be allowed to move to the permanent colony in Iowa.

Equality

The Icarians lived in communal dwellings of dormitories that shared central living and dining areas. All families lived in two equal rooms in an apartment building and had the same kind of furniture. Children were raised in a communal creche, not just by their own parents. Tasks were divided among the group; one might be a seamstress and never need to cook.

Housing

When the Icarians first arrived at Nauvoo on March 15, 1849, they purchased a number of buildings, grounds, houses, cattle and the burned-out Mormon Temple which they intended to use as an academy or school.

After all purchases and repairs were done, the Nauvoo Icarian village consisted of a dwelling of individual apartments, two schools (one for girls and the other for boys), two infirmaries, a pharmacy, a large community kitchen with dining hall, a bakery, a butchery, and a room for laundry facilities. Soon thereafter, a steam-powered flour mill, a distillery, pigsty and sawmill were added. A local coal mine was worked for fuel.

Work

All work was divided by sex. Men worked as tailors, masons, wheelwrights, shoemakers, mechanics, blacksmiths, carpenters, tanners, and butchers. Women worked as cooks, seamstresses, washerwomen and ironers.

To earn money, the Icarians established commerce with the outside world by a small store outside St. Louis. Here they sold their handmade shoes, boots and dresses, and also sold items made by the mills and distillery.

Religion

The Icarians believed in a higher power and had a ten-section principle that briefly stated what they thought was needed in a perfect society.

The religion of choice should have an understanding of the following:

- Evil, Misfortune

- Intelligence

- Causes of Evil

- God and Perfection

- Destiny of Humanity, Happiness

- Sociability

- Perfectibility

- The Remedy

- God, Father of the Human Race

At eighteen years of age, the Icarians were instructed on world religions. Marriage in the community was highly encouraged, almost insisted upon. Divorce was allowed; however, members were encouraged to remarry as soon as possible.

Cabet's book Vrai christianisme (True Christianity) was often read from and formed the dominant influence on religious thought, though it was not intended as a specific instruction on religious observances. In the Iowa colony, the Icarians adopted the practice of an informal religious gathering known as the "Cours Icariens" ("Icarian Course") on Sunday afternoons. In addition to reading from Vrai christianisme and other books, these gatherings included quiet games and conversation.

Culture

Culture in Icaria was the second highest priority, second only to education. The community held several concerts and theatrical productions for the entertainment of its members, performing works such as "The Salamander", "Death to the Rats", "Six Heads in a Hat", or "Fisherman's Daughter".

In Nauvoo, there was a library of over 4,000 books, the biggest in Illinois at the time. The community also distributed a biweekly newspaper titled Colonie Icarienne.

The most important holidays were February 3, the anniversary of the First Departure of Icarians from France, and July 4, the summer festival. On July 4, the refectory was decorated with garlands and boughs; cardboard signs declared "Equality", "Freedom", and "Unity", and banners had quotations like "All for Each; Each for All", "To Each According to Their Needs", and "First Right is to Live; First Duty is to Work". They raised the American flag and played the "Star Spangled Banner" and "America". They travelled into Corning to watch the Fourth of July parade, but they remained apart from the anglophone Americans. At the end of the day, they returned to Icaria (three miles east) for a banquet, dance, and theatrical presentation. Icarians also celebrated Christmas, New Year's Day, and the Fete du Mais, a fall harvest corn festival similar to Thanksgiving.

Women's rights

Men and women were given equal participation opportunities in weekly community assemblies, voting on admissions, constitutional changes, and the election of the officer in charge of clothing and lodging.

Bibliography

- Cabet, Étienne (2009) [1854]. Ce que je ferais si j'avais cinq cent mille dollars (in French). Poitiers: Service Commun de Documentation de l'Université de Poitiers. ISBN 9782370760722. OCLC 864436728.

- Cabet, Étienne (1855). Colonie ou république Icarienne dans les Etats-Unis d'Amérique : son histoire (in French). Paris: Chez l'auteur. OCLC 85798566.

- Icarian Community; Cabet, Étienne (1854). Conditions of admission. Nauvoo, IL, US: Icarian Printing Establishment. OCLC 54271194.

- Cabet, Étienne (1855). Opinion icarienne sur le mariage : organisation icarienne, naturalisation (in French). Paris: Auteur. OCLC 255287992, 457217473, 29620127.

- Cabet, Étienne (1842). "Voyage en Icarie : roman philosophique et social" (in French). Paris: J. Mallet. OCLC 1102119037.

- Cabet, Étienne (April 1917). Translated by Teakle, Thomas. "History and constitution of the Icarian Community". Iowa Journal of History and Politics. Iowa City: The State Historical Society. 15 (2): 214–286. ISSN 0740-8579. OCLC 20683368.

See also

Notes

- Contemporary scholar Robert P. Sutton records this amount as 86,000 francs, or about $3,000 (Sutton 1994, p. 61), while the Brief History of Icaria records the figure as $5,000 (Icarian Community 1880, p. 6).

References

- What is America’s French Icarian Village?

- Roberts 1991, p. 77.

- Hillquit 1903, p. 121.

- Shaw 1884, p. 7.

- Shaw 1884, pp. 7–8.

- Shaw 1884, p. 8.

- Shaw 1884, p. 9.

- A. Sauva, Icarie. Quoted in Shaw 1884, p. 9

- Hillquit 1903, p. 122.

- Shaw 1884, p. 16.

- Roberts 1991, p. 92.

- Hillquit 1903, pp. 122–123.

- Roberts 1991, p. 83.

- Sutton 1994, p. 28.

- Hillquit 1903, p. 123.

- Roberts 1991, p. 79.

- Hillquit 1903, p. 124.

- Hillquit 1903, p. 125.

- Hillquit 1903, pp. 126–127.

- Hillquit 1903, p. 126.

- Pitzer & Boyer 1997, p. 281.

- Hillquit 1903, p. 127.

- Sutton 1994, p. 57.

- Sutton 1994, p. 58.

- Hillquit 1903, p. 128.

- Icarian Community 1880, p. 6.

- Sutton 1994, p. 56.

- Sutton 1994, p. 61.

- Hillquit 1903, p. 129.

- Pitzer & Boyer 1997, p. 282.

- Pitzer & Boyer 1997, p. 283.

- Icarian Community 1880, p. 7.

- Pitzer & Boyer 1997, p. 284.

- Soland 2017, p. 65.

- Baxter's Vineyards & Winery 2013.

- Nordhoff 1875, p. 337.

- Nordhoff 1875, p. 336.

- Nordhoff 1875, pp. 337–338.

- Nordhoff 1875, p. 338.

- Gauthier 1992, pp. 91–92.

- Shaw 1884, p. 127.

- French Icarian Colony Foundation.

- Office of Historic Preservation 2019.

- Shaw 1884, pp. 139–143.

- Gauthier 1992, p. 93.

- Ross & National Icarian Heritage Society 1989, p. 21.

- Hine 1973.

Sources

- "Baxter's History". Baxter's Vineyards & Winery. Nauvoo, Illinois. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- "French Icarian Colony Foundation". French Icarian Colony Foundation. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- Gauthier, Paul S (1992). Quest for Utopia : the Icarians of Adams County : with colonies in Denton County, Texas, Nauvoo, Illinois, Cheltenham, Missouri, and Cloverdale, California. Corning, IA: Gauthier Pub. Co. OCLC 26823716.

- Hillquit, Morris (1903). "History of socialism in the United States". New York; London: Funk & Wagnalls Co. OCLC 894101194.

- Hine, Robert V. (1973) [1953]. "California's utopian colonies". New York: Norton. pp. 58–77. OCLC 1028861073.

- Icarian Community (1880). "Brief history of Icaria : constitution, laws and regulations of the Icarian community". Lse Selected Pamphlets. Corning, IA: Office of Publication, Icaria. JSTOR 60214711. OCLC 778044712.

- Nordhoff, Charles (1875). The communistic societies of the United States : from personal visit and observation. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 331–339. OCLC 1020418629.

- Office of Historic Preservation (2019). "Icaria-Speranza Commune". California State Parks. Sacramento, CA, US: State of California. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019.

- Pitzer, Donald; Boyer, Paul S (1997). America's communal utopias. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 279–296. ISBN 9781469604459. OCLC 593295722.

- Reflections of Icaria, Flint, TX: National Icarian Heritage Society, 1994, OCLC 30870064, 942791990 The magazine of the National Icarian Heritage Society

- Roberts, Leslie J (1991). "Etienne Cabet and his Voyage en Icarie, 1840". Utopian Studies. 2 (1–2): 77–94. ISSN 1045-991X. JSTOR 20719028. OCLC 5542773652.

- Ross, D. W.; National Icarian Heritage Society (1989). A photographic history of Icaria-Speranza : a French utopian experiment at Cloverdale, California. Nauvoo, IL, US: The Society. OCLC 20328420.

- Shaw, Albert (1884). Icaria : a chapter in the history of communism. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 9780790569529. OCLC 681177676.

- Soland, Randall (2017). "Chapter 2: Etienne Cabet and the Icarians at Nauvoo, 1849–1860". Utopian communities of Illinois : heaven on the prairie. Charleston, SC: History Press. pp. 57–66. ISBN 9781439661666. OCLC 1004538134 – via Google Books.

- Sutton, Robert P. (1994). Les Icariens : the utopian dream in Europe and America. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252020674. OCLC 28215643.

- "What is America's French Icarian Village?". French Icarian Colony Foundation. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

Further reading

- Allain, Mathé (1978). France and North America, utopias and utopians : proceedings of the Third Symposium of French-American Studies, March 4-8, 1974. Symposium of French-American Studies. Lafayette, LA: Center for Louisiana Studies, Univ. of Southwestern Louisiana. OCLC 247265884.

- Barnes, Sherman B (June 1941). "An Icarian in Nauvoo". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 34 (2): 233–244. ISSN 0019-2287. JSTOR 40187993. OCLC 5542912492.

- Blick, Boris; Grant, H. Roger (October 1973). "French Icarians in St. Louis". The Bulletin - Missouri Historical Society. St. Louis, MO: Missouri Historical Society. 30: 3–28. ISSN 0026-6590. OCLC 485454966.

- Bush, Robert D. (December 1977). "Communism, Community and Charisma: The Crisis in Icaria at Nauvoo". Old Northwest : A Journal of Regional Life and Letters. Miami University. 13 (4): 409–28. ISSN 0360-5531. OCLC 1006094036.

- Fotion, Janice Clark (1966). Cabet and Icarian communism (PhD). Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa. OCLC 956744250.

- Garno, Diana M (1995). "Gender Dilemmas: 'Equality' and 'Rights' for Icarian Women". Utopian Studies. 6 (2): 52–74. ISSN 1045-991X. JSTOR 20719412. OCLC 5542770374.

- Hinds, William Alfred (2004) [1908]. American communities and co-operative colonies (2nd ed.). Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific. pp. 361–395. ISBN 9781410211521. OCLC 609764632.

- Holloway, Mark (1966). Heavens on earth : utopian communities in America, 1680-1880. New York: Dover Publications. OCLC 1035599611.

- Johnson, Christopher H. (1971). "Communism and the Working Class before Marx: The Icarian Experience". The American Historical Review. Washington, DC: American Historical Association. 76 (3): 642–689. doi:10.2307/1851621. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 1851621. OCLC 4646471755.

- Johnson, Christopher H (1968). Etienne Cabet and the Icarian communist movement in France, 1839-1848 (PhD). University of Wisconsin. OCLC 10566214.

- Johnson, Christopher H (1974). Utopian communism in France : Cabet and the Icarians, 1839-1851. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801408953. OCLC 1223569.

- Larsen, Dale R (1998). Soldiers of humanity : a history and census of the Icarian communities. Nauvoo, IL, US: National Icarian Heritage Society. OCLC 40393187.

- Luke, Kenneth Otto (1973). Nauvoo, Illinois, since the exodus of the Mormons, 1846-1973 (PhD). St. Louis, MO: Saint Louis University. OCLC 1428599.

- National Icarian Heritage Society (1995). Icaria-Speranza : final utopian experiment of Icarians in America : proceedings of the 1989 Cours Icarien Symposium. Navoo, IL, US: National Icarian Heritage Society. OCLC 36656124.

- Piotrowski, Sylvester Anthony (1975) [1935]. Étienne Cabet and the Voyage en Icarie : a study in the history of social thought. Westport, Conn: Hyperion Press. ISBN 9780883552438. OCLC 1857976.

- Rees, Thomas (January 1929). "Nauvoo, Illinois, under Mormon and Icarian Occupations". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 21 (4): 506–524. ISSN 0019-2287. JSTOR 40187583. OCLC 847886264.

- Snider, Felicie Cottet; Graves, William H; Vaughn, T.; Morrison, A. B. (1914). "A Short Sketch of the Life of Jules Leon Cottet, a Former Member of the Icarian Community". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 7 (3): 200–217. ISSN 0019-2287. JSTOR 40194201. OCLC 5542896947.

- Snyder, Lillian M, ed. (1994). Assimilation of Icarians into American life : proceedings of the 1988 Cours Icarien symposium, Nauvoo, Illinois, July 9, 1988. Sunnyvale, CA, US: National Icarian Heritage Society. OCLC 31853938.

- Snyder, Lillian (Autumn 1983). "Family life in the Icarian colony". International Journal of Sociology of the Family. 13 (2): 83–95. ISSN 0020-7667. JSTOR 23027177. OCLC 5547558627.

- Snyder, Lillian M, ed. (1980). Humanistic values of the Icarian movement : proceedings of the Symposium on the "Revelance [sic] of the Icarian Movement to Today's world" (1st ed.). The Country Printer. OCLC 903226311.

- Snyder, Lillian M. (1996). The search for brotherhood, peace, and justice : the story of Icaria. Deep River, IA: Brennan Printing. ISBN 9780965304009. OCLC 1084967766.

- Snyder, Lillian M; Sutton, Robert P, eds. (1987). Immigration of the Icarians to Illinois : proceedings of the Icarian weekend in Nauvoo, Nauvoo, Illinois, July 19 & 20, 1986. Macomb, IL, US: Yeast Printing. OCLC 891986356.

- Sutton, Robert P.; National Icarian Heritage Society, eds. (1993) [1987]. Adaptation of the Icarians to America : proceedings of the 1987 Cours Icarien Symposium, Corning, Iowa and Omaha, Nebraska, July 18 & 19, 1987. Nauvoo, IL, US: National Icarian Heritage Society. OCLC 28203956.

- Sutton, Robert P. (Spring 1986). "Utopian Fraternity: Ideal and Reality in Icarian Recreation". Western Illinois Regional Studies. Macomb IL, US: University Library and the College of Arts and Sciences, Western Illinois University. 9: 19–33. ISSN 0192-1355. OCLC 197969243.

- Vallet, Emile (1971) [1917]. An Icarian communist in Nauvoo: commentary. Springfield: Illinois State Historical Society. ISBN 9780912226064. OCLC 1041132701, 247463.

- Wiegenstein, Steve (August 1, 2006). "The Icarians and Their Neighbors". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 10 (3): 289–295. doi:10.1007/s10761-006-0011-5. ISSN 1092-7697. JSTOR 20853106. OCLC 5544765396. S2CID 143907906.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article "Icarians". |

- "Baxter-Snyder Center for Icarian Studies". wiu.edu. Macomb, IL, US: University Libraries, Western Illinois University. 2010. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011.

- "Lillian Snyder Icarian Living History Foundation". icarianfoundation.org. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- "About Us". French Icarian Colony Foundation. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- "Icarian Community records". Manuscript Collection Descriptions, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU. July 8, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2019.