Sonoma County, California

Sonoma County is a county in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2010 United States Census, its population was 483,878.[3] Its county seat and largest city is Santa Rosa.[5] It is to the north of Marin County and the south of Mendocino County. It is west of Napa County and Lake County.

Sonoma County, California | |

|---|---|

| County of Sonoma | |

| |

Seal | |

| Motto(s): "Agriculture, Industry, Recreation" | |

Location in the U.S. state of California | |

Sonoma County, California Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 38.51°N 122.93°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Region | San Francisco Bay Area |

| Incorporated | February 18, 1850[1] |

| Named for | the city of Sonoma |

| County seat (and largest city) | Santa Rosa |

| Government | |

| • Body | Sonoma County Board of Supervisors |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,768 sq mi (4,580 km2) |

| • Land | 1,576 sq mi (4,080 km2) |

| • Water | 192 sq mi (500 km2) |

| Highest elevation | 4,483 ft (1,366 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 483,878 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 494,336 |

| • Density | 270/sq mi (110/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific Time Zone) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (Pacific Daylight Time) |

| Area code | 707 |

| FIPS code | 06-097 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1657246 |

| Website | sonomacounty |

Sonoma County includes the Santa Rosa-Petaluma Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is part of the San Jose-San Francisco-Oakland, CA Combined Statistical Area. It is the northernmost county in the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area region.

In California's Wine Country region, which also includes Napa, Mendocino, and Lake counties, Sonoma County is the largest producer. It has thirteen approved American Viticultural Areas and more than 350 wineries. The voters have twice approved open space initiatives[6] that have provided funding for public acquisition of natural areas, preserving forested areas, coastal habitat, and other open space. More than 8.4 million tourists visit each year, spending more than $1 billion in 2016.

In 2012, Sonoma County ranked as the 22nd county in the United States in agricultural production.[7] By 1920, Sonoma County was ranked as the eighth most agriculturally productive US county and a leading producer of hops, grapes, prunes, apples, and dairy and poultry products,[8] largely due to the extent of available, fertile agricultural land in addition to the abundance of high quality water for irrigation. As of 2009, agriculture was largely divided between two nearly monocultural uses: grapes and pasturage

History

The Pomo, Coast Miwok and Wappo peoples were the earliest human settlers of Sonoma County, between 8000 and 5000 BC, effectively living within the natural carrying capacity of the land. Archaeological evidence of these First people includes a number of occurrences of rock carvings, especially in southern Sonoma County; these carvings often take the form of pecked curvilinear nucleated design.

Spaniards, Russians, and other Europeans claimed and settled in the county from the late 16th to mid-19th century, seeking timber, fur, and farmland. The Russians were the first newcomers to establish a permanent foothold in Sonoma County, with the Russian-American Company establishing Fort Ross on the Sonoma Coast in 1812. This settlement and its outlying Russian settlements came to include a population of several hundred Russian and Aleut settlers and a stockaded fort with artillery. However, the Russians abandoned it in 1841 and sold the fort to John Sutter, settler and Mexican land grantee of Sacramento.

The Mission San Francisco Solano, founded in 1823 as the last and northernmost of 21 California missions, is in the present City of Sonoma, at the northern end of El Camino Real. El Presidio de Sonoma, or Sonoma Barracks (part of Spain's Fourth Military District), was established in 1836 by Comandante General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo. His duties included keeping an eye on the Russian traders at Fort Ross, secularizing the Mission, maintaining cooperation with the Native Americans of the entire region, and doling out the lands for large estates and ranches. The City of Sonoma was the site of the Bear Flag Revolt in 1846.

Sonoma was one of the original counties when California became a state in 1850,[9] with its county seat originally the town (now city) of Sonoma. However, by the early 1850s, Sonoma had declined in importance in both commerce and population, its county buildings were crumbling, and it was relatively remote. As a result, elements in the newer, rapidly growing towns of Petaluma, Santa Rosa, and Healdsburg began vying to move the county seat to their towns. The dispute ultimately was between the bigger, richer commercial town of Petaluma and the more centrally located, growing agricultural center of Santa Rosa. The fate was decided following an election for the state legislature in which James Bennett of Santa Rosa defeated Joseph Hooker of Sonoma and introduced a bill that resulted in Santa Rosa being confirmed as county seat in 1854.[10] Allegedly, several Santa Rosans, not caring to wait, decided to take action and, one night, rode down the Sonoma Valley to Sonoma, took the county seals and records, and brought them to Santa Rosa.[11] Some of the county's land was annexed from Mendocino County between 1850 and 1860.

Early post-1847 settlement and development focused primarily on the city of Sonoma, then the region's sole town and a common transit and resting point in overland travel between the region and Sacramento and the gold fields to the east. However, after 1850, a settlement that soon became the city of Petaluma began to grow naturally near the farthest navigable point inland up the Petaluma River. Originally a hunting camp used to obtain game to sell in other markets, by 1854 Petaluma had grown into a bustling center of trade, taking advantage of its position in the river near a region of highly productive agricultural land that was being settled. Soon, other inland towns, notably Santa Rosa and Healdsburg began to develop similarly due to their locations along riparian areas in prime agricultural flatland. However, their development initially lagged behind Petaluma which, until the arrival of railroads in the 1860s, remained the primary commercial, transit, and break-of-bulk point for people and goods in the region. After the arrival of the San Francisco and North Pacific Railroad in 1870, Santa Rosa began to boom, soon equalling and then surpassing Petaluma as the region's population and commercial center. The railroad bypassed Petaluma for southern connections to ferries of San Francisco Bay.

Six nations have claimed Sonoma County from 1542 to the present:

| Spanish Empire, 1542, by sea, voyage of Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo as far as the Russian River. Later validated by voyage of Sebastián Vizcaíno, 1602. | |

| Kingdom of England, June 1579, voyage of the Golden Hind under Captain Francis Drake at Bodega Bay (exact location disputed). | |

| Spanish Empire, October 1775, the Sonora at Bodega Bay, under Lt. Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, until 1821, when Mexico gained independence from Spain. | |

| Russian Empire, by Russian-American Company expedition led by Ivan Alexandrovich Kuskov, the founder of Fort Ross and, from 1812 to 1821, its colonial administrator. Note: There is an overlap of rule with the Mexican Empire (next item), until the Russians sold Fort Ross in 1841 to John Sutter, before leaving the area in 1842. | |

| First Mexican Empire, August 1821, under Emperor Agustin Iturbide (October 1822, probable time new flag raised in California), until 1823. | |

| Mexican Republic, 1823 until June 1846. | |

| California Republic, June 14, 1846 until July 9, 1846. | |

| United States of America, July 9, 1846 to present. |

Sonoma County was severely shaken by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. The displacements along the fault averaged 15 feet (4.6 m).[12]

In October 2017, the county was greatly affected by the Tubbs Fire[13] and the Nuns Fire. In late October and early November 2019, the Kincade Fire burned 77,758 acres (31,468 ha), almost all in Sonoma County. In August and September 2020, the Walbridge Fire burned 55,209 acres (22,342 ha) in the western part of the county; then in September-October the Glass fire affected the city of Santa Rosa and ultimately destroying 1,000+ buildings[14]The county also had a wildfire in the 1870s that is compared to the Hanley fire and Tubbs fire because they burned in the same path.

The Sonoma County Landmarks Commission recognizes nearly 200 formal historical landmarks and the Sonoma County Historical Society counts 380 landmarks recognized by several agencies.

Etymology

According to the book California Place Names, "The name of the Indian tribe is mentioned in baptismal records of 1815 as Chucuines o Sonomas, by Chamisso in 1816 as Sonomi, and repeatedly in Mission records of the following years."[15]

According to the Coast Miwok and the Pomo tribes that lived in the region, Sonoma translates as "valley of the moon" or "many moons". Their legends detail this as a land where the moon nestled, hence the names Sonoma Valley and the "Valley of the Moon."[16] This translation was first recorded in an 1850 report by General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo to the California Legislature.[17] Jack London popularized it in his 1913 novel The Valley of the Moon.

In the native languages there is also a constantly recurring ending tso-noma, from tso, the earth; and noma, village; hence tsonoma, "earth village."[18] Other sources say Sonoma comes from the Patwin tribes west of the Sacramento River, and their Wintu word for "nose". Per California Place Names, "the name is doubtless derived from a Patwin word for 'nose', which Padre Arroyo (Vocabularies, p. 22) gives as sonom (Suisun)." Spaniards may have found an Indian chief with a prominent protuberance and applied the nickname of Chief Nose to the village and the territory.[19] The name may have applied originally to a nose-shaped geographic feature.[15]

Jesse Sawyer argues that it is from Wappo tso-noma, meaning "redwood place."[20]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has an area of 1,768 square miles (4,580 km2), of which 1,576 square miles (4,080 km2) is land and 192 square miles (500 km2) (10.9%) is water.[21]

The county lies in the North Coast Ranges of northwestern California. Its ranges include the Mayacamas and the Sonoma Mountains, the southern peak of the latter being the prominent landform Sears Point. The highest peak in the Mayacamas within the county and the highest peak in the County is Mt. Saint Helena. It has uncommon occurrences of pygmy forest, dominated by Mendocino cypress. The highest peak of the Sonoma Mountains is Sonoma Mountain itself, which boasts two significant public access properties: Jack London State Historic Park and Fairfield Osborn Preserve.

The county includes the City of Sonoma and the Sonoma Valley, in which the City of Sonoma is located. However, these are not synonymous. The City of Sonoma is merely one of nine incorporated cities in the county. The Sonoma Valley is just the southeastern portion of the county, which includes many other valleys and geographic zones, including the Petaluma Valley, the Santa Rosa Plains, the Russian River, the Alexander Valley, and the Dry Creek Valley.

Distinct habitat areas within the county include oak woodland, redwood forest, northern coastal scrub, grassland, marshland, oak savanna and riparian woodland. The California oak woodland in the upper Yulupa Creek and Spring Creek watersheds in Annadel State Park is a relatively undisturbed ecosystem with considerable biodiversity. These forested areas have been characterized as some of the best examples of such woodlands.[22] An unusual characteristic of these forests is the high content of undisturbed prehistoric bunchgrass understory, testifying to the absence of historic grazing or other agriculture.

Trees of the oak woodland habitat include Pacific madrone, Douglas fir, coast live oak, Garry oak, and California laurel. Common understory plants are toyon, poison oak, and, at the fringes, coast silk-tassel.

Climate

Sonoma County, as is often the case with coastal counties in California, has a great degree of climatic variation and numerous, often very different, microclimates.[23][24] Key determining factors for local climate are proximity to the ocean, elevation, and the presence and elevation of hills or mountains to the east and west. This is in large part due to the fact that, as throughout California, the prevailing weather systems and wind come normally from the Pacific Ocean, blowing in from the west and southwest, so that places closer to the ocean and on the windward side of higher elevations tend to receive more rain from autumn through spring and more summer wind and fog. This itself is partly a result of the presence of high and low pressures in inland California, with persistent high summer temperatures in the Central Valley, in particular, leading to low pressures, drawing in moist air from the Pacific, cooling into damp cool breezes and fog over the cold coastal water. Those places further inland and particularly in the lee of significant elevations tend to receive less rain and less, in some cases no, fog in the summer.

The coast itself is typically cool and moist throughout summer, often foggy, with fog generally blowing in during the late afternoon and evening until it clears in the later morning becoming sunny, before repeating. Coastal summer highs are typically in the mid to high 60s, warming to the low 70s further from the ocean.

Certain inland areas, including the Petaluma area and the Santa Rosa Plain, are also prone to this normal fog pattern in general.[24] However, they tend to receive the fog later in the evening, the fog tends to be more short-lived, and mid-day temperatures are significantly higher than they are on the coast, typically in the low 80s F. This is particularly true for Petaluma, Cotati, and Rohnert Park, and, only slightly less so, Santa Rosa, Windsor, and Sebastopol. In large part, this results from lower elevations and the prominent Petaluma Gap in the hills between the ocean to the west and the Petaluma Valley and Santa Rosa Plain to the east.

Areas north of Santa Rosa and Windsor, with larger elevations to the west and further from the fog path, tend to receive less fog and less summer marine influence. Healdsburg, to the north of Windsor, is less foggy and much warmer, with summer highs typically in the higher 80s to about 90 °F (32 °C). Sonoma and the Sonoma Valley, east of Petaluma, are similar, with highs typically in the very high 70s F to 80 °F (27 °C). This is in part due to the presence of the Sonoma Mountains between Petaluma and Sonoma. Cloverdale, far to the north and outside of the Santa Rosa Plain, is significantly hotter than any other city in the county, with rare evening-morning fog and highs often in the 90s, reaching 100 °F (38 °C) much more frequently than the other cities. Notably, however, the temperature differences among the different areas of the county are greatest for the highs during mid-day, with the diurnal lows much more even throughout the entire county. The lows are closely tied to the evening-morning cooling marine influence, in addition to elevation, bringing similarly cool temperatures to much of region.

These weather patterns contribute to high diurnal temperature fluctuations in much of the county. In summer, daily lows and highs are typically 30–40 °F apart inland, with highs for Petaluma, Cotati, Rohnert Park, Santa Rosa, Windsor, and Sebastopol typically being in the very low 80s F and lows at or near 50 °F (10 °C). Healdsburg and the City of Sonoma, with similar lows, have even greater diurnal fluctuations due to their significantly warmer highs. On the other hand, the coast, with strong marine influence, tends to have low diurnal temperature fluctuation, with summer highs much cooler than the inland towns, typically 65–75 °F, yet lows in the high 40s to low 50s F, fairly comparable to most inland towns.

These microclimates are evident during the rainy seasons as well, with great variation in the amount of rainfall throughout the county. Generally, all of Sonoma County receives a fair amount of rain, with much of the county receiving between about 25 in (640 mm), comparable to areas such as Sonoma and Petaluma, and roughly 30 in (760 mm) normal for Santa Rosa. However, certain areas, particularly in the north-west portion of the county around the Russian River, receive significantly more rainfall. The Guerneville area, for example, typically receives about 50 in (1,300 mm) of rain a year, with annual rain occasionally going as high as 70 in (1,800 mm). Nearby Cazadero typically receives about 72 in (1,800 mm) of rain a year, many times has reached over 100 in (2,500 mm) a year, and sometimes over 120 in (3,000 mm) of rain in a year. The Cazadero region is the second wettest place in California after Gasquet.[25]

Snow is exceedingly rare in Sonoma County, except in the higher elevations on and around the Mayacamas Mountains, particularly Mount Saint Helena, and Cobb Mountain, whose peak is in Lake County.[26]

Ocean, bays, rivers and streams

Sonoma County is bounded on the west by the Pacific Ocean, and has 76 miles (122 km) of coastline. The major coastal hydrographic features are Bodega Bay, the mouth of the Russian River, and the mouth of the Gualala River, at the border with Mendocino County. All of the county's beaches were listed as among the cleanest in the state in 2010.[27]

Six of the county's nine cities, from Healdsburg south through Santa Rosa to Rohnert Park and Cotati, are in the Santa Rosa Plain. The northern Plain drains directly to the Russian River, or to a tributary; the southern Plain drains to the Russian River via the Laguna de Santa Rosa.

Russian River

Much of central and northern Sonoma County is in the watershed of the Russian River and its tributaries. The river rises in the coastal mountains of Mendocino County, north of the city of Ukiah, and flows into Lake Mendocino, a major flood control reservoir. The river flows south from the lake through Mendocino to Sonoma County, paralleled by Highway 101. It turns west at Healdsburg, receiving water from Lake Sonoma via Dry Creek, and empties into the Pacific Ocean at Jenner.

Laguna de Santa Rosa

The Laguna de Santa Rosa is the largest tributary of the Russian River.[28] It is 14 miles (23 km) long, running north from Cotati to the Russian River near Forestville. Its flood plain is more than 7,500 acres (30 km2). It drains a 254-square-mile (660 km2) watershed, including most of the Santa Rosa Plain.

The Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation says:[29]

The Laguna de Santa Rosa is Sonoma County's richest area of wildlife habitat, and the most biologically diverse region of Sonoma County (itself the second-most biologically diverse county in California)... It is a unique ecological system covering more than 30,000 acres (120 km2) and comprisedof a mosaic of creeks, open water, perennial marshes, seasonal wetlands, riparian forests, oak woodlands, and grasslands... As the receiving water of a watershed where most of the county's human population lives, it is a landscape feature of critical importance to Sonoma County's water quality, flood control, and biodiversity.

The Laguna's largest tributary is Santa Rosa Creek, which runs through Santa Rosa. Its major tributaries are Brush Creek, Mark West Creek, Matanzas Creek, Spring Creek, and Piner Creek. Santa Rosa Creek was shown to be polluted in Sonoma county first flush results.[30]

Other water bodies

The boundary with Marin County runs from the mouth of the Estero Americano at Bodega Bay, up Americano Creek, then overland to San Antonio Creek and down the Petaluma River to its mouth at the northwest corner of San Pablo Bay, which adjoins San Francisco Bay. The southern edge of Sonoma County comprises the northern shore of San Pablo Bay between the Marin County border at the Petaluma River and the border with Solano County at Sonoma Creek. Sonoma County has no incorporated communities directly on the shore of San Pablo Bay. At the present, there is only a private marina with related facilities called Port Sonoma near the mouth of the Petaluma River. However, the Petaluma River, which flows into San Pablo Bay, is navigable up to the city of Petaluma.

The Petaluma River, Tolay Creek, and Sonoma Creek enter the bay at the county's southernmost tip. The intertidal zone where they join the bay is the vast Napa Sonoma Marsh.

Americano Creek, the Petaluma River, Tolay Creek, and Sonoma Creek are the principal streams draining the southern portion of the county. The Sonoma Valley is drained by Sonoma Creek, whose major tributaries are Yulupa Creek, Graham Creek, Calabazas Creek, Schell Creek, and Carriger Creek; Arroyo Seco Creek is tributary to Schell Creek. Other creeks include Foss, Felta, and Mill.

Lakes and reservoirs in the county include Lake Sonoma, Tolay Lake, Lake Ilsanjo, Santa Rosa Creek Reservoir, Lake Ralphine, and Fountaingrove Lake.

Marine protected areas of Sonoma County

Like underwater parks, these marine protected areas help conserve ocean wildlife and marine ecosystems.

- Del Mar Landing State Marine Reserve

- Stewarts Point State Marine Reserve & Stewarts Point State Marine Conservation Area

- Salt Point State Marine Conservation Area

- Gerstle Cove State Marine Reserve

- Russian River State Marine Reserve and Russian River State Marine Conservation Area

- Bodega Head State Marine Reserve & Bodega Head State Marine Conservation Area

- Estero Americano State Marine Recreational Management Area

Threatened/endangered species

A number of endangered plants and animals are found in Sonoma County, including the California clapper rail (Rallus longirostris obsoletus), salt marsh harvest mouse (Reithrodontomys raviventris), northern red-legged frog (Rana aurora), Sacramento splittail (Pogonichthys macrolepidotus), California freshwater shrimp (Syncaris pacifica), showy Indian clover (Trifolium amoenum), and Hickman's potentilla (Potentilla hickmanii).

Species of special local concern include the California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense) and some endangered plants, including Burke's goldfields (Lasthenia burkei), Sebastopol meadowfoam (Limnanthes vinculans), and Sonoma sunshine or Baker's stickyseed (Blennosperma bakeri).

Endangered species that are endemic to Sonoma County include Sebastopol meadowfoam, Sonoma sunshine, and Pitkin Marsh lily (Lilium pardalinum subsp. pitkinense).

The Sonoma County Water Agency has had a Fisheries Enhancement Program since 1996. Its website says:[31]

"The primary focus of the FEP is to enhance habitat for three salmonids: Steelhead, Chinook salmon, and Coho salmon. These three species are listed as threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. The California Department of Fish and Game considers the Coho salmon endangered."

Adjacent counties

- Mendocino County, California – north

- Lake County, California – northeast

- Napa County, California – east

- Solano County, California – southeast

- Marin County, California – south

- Contra Costa County, California – south-southeast[32][33]

National protected area

Transportation

Major highways

U.S. Route 101 is the westernmost Federal highway in the U.S.A. Running north/south through the states of California, Oregon, and Washington, it generally parallels the coastline from the Mexico–US border to the Canada–US border. Highway 101 links seven of the county's nine incorporated cities: Cloverdale, Healdsburg, Windsor, Santa Rosa, Rohnert Park, Cotati, and Petaluma. It is a freeway for its entire length within the county.

The four-lane sections of the highway have been heavily congested during peak commute hours for many years and work is being done to widen part of the highway to six lanes. The segment from north of Petaluma (at Old Redwood Highway/Petaluma Boulevard North exit) to Windsor has been fully widened, as has the segment from the Petaluma River bridge to the Marin County border. The two new inner lanes are designated for vehicles with two or more occupants during commute hours. Work is being done around Petaluma to finish the widening within Sonoma County; the widening also involves upgrading the highway to full freeway standards.

Within Sonoma County, Highway 1 follows the coastline from the Mendocino County border, at the mouth of the Gualala River, to the Marin County border, at the Estero Americano (Americano Creek), southeast of Bodega Bay.

Highway 12 runs eastward from its intersection with Highway 116 in Sebastopol to Santa Rosa. There it turns south through the Valley of the Moon to Sonoma, then east into Napa County. The four-lane freeway section within Santa Rosa, between Fulton Road and Farmers Lane, is called the Luther Burbank Memorial Highway. That section, especially where it crosses Highway 101, is severely congested during peak commute hours.

The two-lane Bodega Highway runs west from the intersection of Highways 12 and 116 in Sebastopol, through the coastal hills to its intersection with Highway 1, east of Bodega Bay. East of Santa Rosa, Highway 12 is also called Sonoma Highway; and east of the City of Sonoma, Carneros Highway.

Highway 37 connects Highway 101 at Novato, in Marin County, with Interstate 80 in Vallejo, in Solano County, at the top of San Pablo Bay. Within Sonoma County, it is also called Sears Point Road.

Highway 116 is a winding, two-lane rural route that runs from Jenner, at the mouth of the Russian River on the coast, southeast to Arnold Drive near Sonoma. It is also called Guerneville Highway, between Guerneville and Forestville; Gravenstein Highway North, between Forestville and Sebastopol; and Gravenstein Highway South, between Sebastopol and Stony Point Road, west of Rohnert Park. East of Petaluma it is called Lakeville Highway, then Stage Gulch Road.

Highway 121 is a two-lane rural route running from Highway 37 near Sears Point Raceway to Highway 128 in Lake Berryessa, in Napa County.

The northernmost section of Highway 128 is a two-lane, rural route running southeast from Highway 101 at Geyserville, north of Healdsburg, through the Alexander Valley and into Napa County.

Public transportation

- Sonoma County Transit is the countywide transit operator, providing service to all cities in Sonoma County.

- CityBus operates within the city limits of Santa Rosa.[34]

- The cities of Cloverdale and Petaluma also provide their own local bus service.

- Golden Gate Transit connects Santa Rosa and points south with Marin County and San Francisco.

- Mendocino Transit Authority runs north from Santa Rosa to Ukiah (via US 101) and to the coast (via California Routes 12 and 1).

- Sonoma–Marin Area Rail Transit (SMART) is a commuter rail line eventually planned to go between Larkspur in Marin County and Cloverdale in Sonoma County. As of December 2020 the line operates between Larkspur and the Sonoma County Airport.

Airports

The Charles M. Schulz - Sonoma County Airport is at 2290 Airport Boulevard, west of Highway 101, between Santa Rosa and Windsor. Its main runway is 5,115 feet (1,559 m) long and 150 feet (46 m) wide, and can accommodate planes up to 95,000 pounds (43,000 kg) maximum gross takeoff weight. It offers fuel, major maintenance, hangar space, and tie-downs for local and transient aircraft. Alaska Airlines, American Airlines, and United Airlines offer regular daily commercial flights.

There are five general aviation airports within the county:

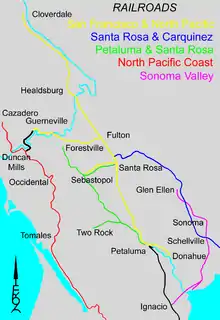

Railroads

In 1864, the Petaluma and Haystack Railroad connected the city of Petaluma to a ferry landing at the head of navigation on the Petaluma River.

In 1870, the San Francisco and North Pacific Railroad (SF&NP) connected the City of Santa Rosa to ferry connections at Donahue landing on the Petaluma River. Rail service was extended north to Healdsburg in 1871 and Cloverdale in 1872. In 1884 the railroad was extended south to an alternate ferry connection in Tiburon. This rail line serves as the primary route of Sonoma–Marin Area Rail Transit.[35]

The 3-foot-gauge North Pacific Coast Railroad extended northward in 1876 from a ferry connection at Sausalito through Valley Ford, Freestone, and Occidental to Monte Rio on the lower Russian River. Service was extended to Duncans Mills in 1877 and Cazadero in 1885. The standard gauge Fulton and Guerneville Railroad left the SF&NP at Fulton to reach Korbel in 1876 and Guerneville in 1877. Standard-gauge rails were extended down-river to Duncan Mills in 1909 after the Northwestern Pacific Railroad merger, and narrow-gauge service was discontinued in 1930. The standard-gauge route became River Road after tracks were removed in 1935.[36]

The unique Sonoma Valley Prismoidal Railway linked the city of Sonoma to bay ferries in 1876 and was replaced in 1879 by the 3-foot (0.91 m)-gauge Sonoma Valley Railroad to a ferry landing near the mouth of the Petaluma River. Service was extended from Sonoma to Glen Ellen in 1882. The southern end of the line was extended westward in 1888 to a connection with the SF&NP at Ignacio. This line was converted to standard-gauge in 1890 and remains (in 2018) as Sonoma County's connection to the national rail system at Schellville.

Southern Pacific subsidiary Santa Rosa and Carquinez Railroad extended eastward in 1888 to link Santa Rosa with the national rail system. The portion between Sonoma and Santa Rosa was dismantled in the 1940s after interchange shifted to the former Sonoma Valley line.[37]

A SF&NP branch line from Santa Rosa brought rail service to Sebastopol in 1890. The Petaluma and Santa Rosa Railroad extended interurban service north from a ferry connection in Petaluma to reach Sebastopol in 1904, Santa Rosa in 1905, and Forestville in 1906. Portions of this line were converted to the Joe Rodota Trail after tracks were removed in the 1980s.[38]

The Sonoma–Marin Area Rail Transit commuter rail line inaugurated passenger service on August 25, 2017,[39] utilizing the Northwestern Pacific Railroad right-of-way from Sonoma County Airport station to Larkspur Landing in Marin. The system is planned to extend to Cloverdale Depot.

Crime

The following table includes the number of incidents reported and the rate per 1,000 persons for each type of offense in the year of 2009.

| Population and crime rates | ||

|---|---|---|

| Population[40] | 478,551 | |

| Violent crime[41] | 1,917 | 4.01 |

| Homicide[41] | 9 | 0.02 |

| Forcible rape[41] | 163 | 0.34 |

| Robbery[41] | 318 | 0.66 |

| Aggravated assault[41] | 1,427 | 2.98 |

| Property crime[41] | 4,537 | 9.48 |

| Burglary[41] | 1,993 | 4.16 |

| Larceny-theft[41][note 1] | 6,671 | 13.94 |

| Motor vehicle theft[41] | 786 | 1.64 |

| Arson[41] | 85 | 0.18 |

Cities by population and crime rates

| Cities by population and crime rates | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Population[42] | Violent crimes[42] | Violent crime rate per 1,000 persons |

Property crimes[42] | Property crime rate per 1,000 persons | |||

| Cloverdale | 8,775 | 6 | 0.68 | 157 | 17.89 | |||

| Cotati | 7,398 | 54 | 7.30 | 85 | 11.49 | |||

| Healdsburg | 11,458 | 18 | 1.57 | 271 | 23.65 | |||

| Petaluma | 58,995 | 167 | 2.83 | 822 | 13.93 | |||

| Rohnert Park | 41,716 | 192 | 4.60 | 770 | 18.46 | |||

| Santa Rosa | 170,862 | 636 | 3.72 | 3,818 | 22.35 | |||

| Sebastopol | 7,512 | 8 | 1.06 | 170 | 22.63 | |||

| Sonoma | 10,841 | 27 | 2.49 | 193 | 17.80 | |||

| Windsor | 27,293 | 67 | 2.45 | 318 | 11.65 | |||

Demographics

2011

| Population, race, and income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population[40] | 478,551 | ||||

| White[40] | 390,474 | 81.6% | |||

| Black or African American[40] | 7,161 | 1.5% | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native[40] | 5,962 | 1.2% | |||

| Asian[40] | 19,249 | 4.0% | |||

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander[40] | 1,513 | 0.3% | |||

| Some other race[40] | 37,977 | 7.9% | |||

| Two or more races[40] | 16,215 | 3.4% | |||

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race)[43] | 116,222 | 24.3% | |||

| Per capita income[44] | $33,119 | ||||

| Median household income[45] | $64,343 | ||||

| Median family income[46] | $78,227 | ||||

Places by population, race, and income

| Places by population and race | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | Type[47] | Population[40] | White[40] | Other[40] [note 2] |

Asian[40] | Black or African American[40] |

Native American[40] [note 3] |

Hispanic or Latino (of any race)[43] |

| Bloomfield | CDP | 186 | 93.0% | 0.0% | 7.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.2% |

| Bodega | CDP | 132 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Bodega Bay | CDP | 772 | 87.2% | 3.5% | 9.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4.9% |

| Boyes Hot Springs | CDP | 7,284 | 74.8% | 20.8% | 3.4% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 52.7% |

| Carmet | CDP | 22 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Cazadero | CDP | 305 | 92.8% | 7.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 8.9% |

| Cloverdale | City | 8,390 | 81.1% | 13.6% | 4.6% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 30.2% |

| Cotati | City | 7,154 | 87.9% | 6.2% | 4.4% | 1.2% | 0.2% | 10.5% |

| Eldridge | CDP | 1,899 | 74.6% | 22.9% | 1.8% | 0.5% | 0.2% | 19.0% |

| El Verano | CDP | 3,555 | 80.6% | 13.3% | 5.5% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 28.2% |

| Fetters Hot Springs-Agua Caliente | CDP | 4,034 | 88.7% | 7.1% | 2.9% | 0.7% | 0.6% | 41.2% |

| Forestville | CDP | 3,268 | 86.6% | 10.0% | 3.1% | 0.0% | 0.2% | 10.7% |

| Fulton | CDP | 691 | 54.6% | 36.0% | 9.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 36.0% |

| Geyserville | CDP | 1,024 | 58.1% | 37.6% | 2.4% | 0.0% | 1.9% | 56.7% |

| Glen Ellen | CDP | 549 | 91.4% | 7.3% | 0.0% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 10.4% |

| Graton | CDP | 1,621 | 83.0% | 14.4% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 2.3% | 22.8% |

| Guerneville | CDP | 4,187 | 90.6% | 5.4% | 0.3% | 2.1% | 1.6% | 11.6% |

| Healdsburg | City | 11,161 | 79.1% | 17.7% | 0.3% | 0.8% | 2.2% | 33.0% |

| Jenner | CDP | 113 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Kenwood | CDP | 509 | 80.6% | 17.3% | 2.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 18.3% |

| Larkfield-Wikiup | CDP | 8,569 | 88.3% | 7.7% | 3.3% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 17.6% |

| Monte Rio | CDP | 1,044 | 91.9% | 5.9% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 1.4% | 2.4% |

| Occidental | CDP | 1,264 | 88.8% | 5.9% | 4.0% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 4.8% |

| Penngrove | CDP | 2,428 | 90.6% | 8.6% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 12.8% |

| Petaluma | City | 57,265 | 83.5% | 9.2% | 5.1% | 1.0% | 1.1% | 21.3% |

| Rohnert Park | City | 40,741 | 78.6% | 11.5% | 6.6% | 2.0% | 1.4% | 23.3% |

| Roseland | CDP | 6,628 | 67.6% | 27.1% | 2.9% | 1.8% | 0.5% | 58.5% |

| Salmon Creek | CDP | 95 | 93.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6.3% | 0.0% |

| Santa Rosa | City | 164,976 | 78.2% | 12.5% | 5.1% | 2.3% | 1.9% | 28.2% |

| Sea Ranch | CDP | 812 | 97.9% | 0.7% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 7.4% |

| Sebastopol | City | 7,359 | 88.8% | 6.8% | 1.2% | 0.7% | 2.5% | 10.8% |

| Sereno del Mar | CDP | 119 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Sonoma | City | 10,430 | 87.5% | 8.0% | 2.1% | 0.4% | 1.9% | 16.6% |

| Temelec | CDP | 1,510 | 97.3% | 1.7% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 10.2% |

| Timber Cove | CDP | 165 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 13.9% |

| Valley Ford | CDP | 85 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 43.5% |

| Windsor | Town | 26,229 | 80.1% | 12.7% | 3.0% | 0.6% | 3.7% | 32.2% |

| Places by population and income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | Type[47] | Population[48] | Per capita income[44] | Median household income[45] | Median family income[46] |

| Bloomfield | CDP | 186 | $31,592 | $85,515 | $85,735 |

| Bodega | CDP | 132 | $26,221 | $21,750 | $40,972 |

| Bodega Bay | CDP | 772 | $52,512 | $73,250 | $122,500 |

| Boyes Hot Springs | CDP | 7,284 | $24,218 | $47,123 | $48,382 |

| Carmet | CDP | 22 | [49] | [49] | [49] |

| Cazadero | CDP | 305 | $32,407 | $46,875 | $53,500 |

| Cloverdale | City | 8,390 | $25,745 | $56,649 | $71,233 |

| Cotati | City | 7,154 | $38,863 | $62,969 | $77,350 |

| Eldridge | CDP | 1,899 | $28,397 | $94,688 | $105,724 |

| El Verano | CDP | 3,555 | $27,189 | $49,731 | $53,409 |

| Fetters Hot Springs-Agua Caliente | CDP | 4,034 | $29,849 | $59,315 | $63,879 |

| Forestville | CDP | 3,268 | $32,773 | $53,095 | $65,135 |

| Fulton | CDP | 691 | $25,734 | $42,692 | $125,417 |

| Geyserville | CDP | 1,024 | $23,915 | $49,375 | $51,250 |

| Glen Ellen | CDP | 549 | $33,389 | $45,558 | $56,250 |

| Graton | CDP | 1,621 | $36,676 | $77,574 | $91,946 |

| Guerneville | CDP | 4,187 | $30,594 | $39,459 | $61,250 |

| Healdsburg | City | 11,161 | $34,031 | $63,666 | $72,235 |

| Jenner | CDP | 113 | $45,432 | $81,161 | $42,422 |

| Kenwood | CDP | 509 | $76,096 | $56,250 | $144,318 |

| Larkfield-Wikiup | CDP | 8,569 | $33,798 | $71,046 | $92,243 |

| Monte Rio | CDP | 1,044 | $21,861 | $31,667 | $41,544 |

| Occidental | CDP | 1,264 | $46,895 | $67,205 | $104,375 |

| Penngrove | CDP | 2,428 | $39,270 | $84,315 | $98,407 |

| Petaluma | City | 57,265 | $35,111 | $76,185 | $92,192 |

| Rohnert Park | City | 40,741 | $28,203 | $56,950 | $71,726 |

| Roseland | CDP | 6,628 | $20,518 | $54,255 | $60,104 |

| Salmon Creek | CDP | 95 | $70,087 | $80,694 | $80,694 |

| Santa Rosa | City | 164,976 | $30,085 | $60,850 | $69,944 |

| Sea Ranch | CDP | 812 | $48,998 | $57,227 | $79,063 |

| Sebastopol | City | 7,359 | $35,459 | $60,000 | $85,391 |

| Sereno del Mar | CDP | 119 | $120,019 | $162,986 | $162,986 |

| Sonoma | City | 10,430 | $42,261 | $63,262 | $104,942 |

| Temelec | CDP | 1,510 | $37,406 | $39,274 | $44,960 |

| Timber Cove | CDP | 165 | $39,092 | $42,143 | $58,250 |

| Valley Ford | CDP | 85 | [49] | [49] | [49] |

| Windsor | Town | 26,229 | $31,009 | $77,157 | $86,425 |

2010

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 560 | — | |

| 1860 | 11,867 | 2,019.1% | |

| 1870 | 19,819 | 67.0% | |

| 1880 | 25,926 | 30.8% | |

| 1890 | 32,721 | 26.2% | |

| 1900 | 38,480 | 17.6% | |

| 1910 | 48,394 | 25.8% | |

| 1920 | 52,090 | 7.6% | |

| 1930 | 62,222 | 19.5% | |

| 1940 | 69,052 | 11.0% | |

| 1950 | 103,405 | 49.7% | |

| 1960 | 147,375 | 42.5% | |

| 1970 | 204,885 | 39.0% | |

| 1980 | 299,681 | 46.3% | |

| 1990 | 388,222 | 29.5% | |

| 2000 | 458,614 | 18.1% | |

| 2010 | 483,878 | 5.5% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 494,336 | [4] | 2.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[50] 1790–1960[51] 1900–1990[52] 1990–2000[53] 2010–2015[3] | |||

The 2010 United States Census reported that Sonoma County had a population of 483,878. The racial makeup of Sonoma County was 371,412 (76.8%) White, 7,610 (1.6%) African American, 6,489 (1.3%) Native American, 18,341 (3.8%) Asian, 1,558 (0.3%) Pacific Islander, 56,966 (11.8%) from other races, and 21,502 (4.4%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 120,430 persons (24.9%).[54]

| Population reported at 2010 United States Census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Population | American | American | Islander | races | more races | or Latino (of any race) | |||

| Sonoma County | 483,878 | 371,412 | 7,610 | 6,489 | 18,341 | 1,558 | 56,966 | 21,502 | 120,430 |

cities and towns | Population | American | American | Islander | races | more races | or Latino (of any race) | ||

| Cloverdale | 8,618 | 6,458 | 48 | 156 | 98 | 7 | 1,530 | 321 | 2,824 |

| Cotati | 7,265 | 5,929 | 122 | 75 | 283 | 30 | 427 | 399 | 1,255 |

| Healdsburg | 11,254 | 8,334 | 56 | 205 | 125 | 18 | 2,133 | 383 | 3,820 |

| Petaluma | 57,941 | 46,566 | 801 | 353 | 2,607 | 129 | 5,103 | 2,382 | 12,453 |

| Rohnert Park | 40,971 | 31,178 | 759 | 407 | 2,144 | 179 | 3,967 | 2,337 | 9,068 |

| Santa Rosa | 167,815 | 119,158 | 4,079 | 2,808 | 8,746 | 810 | 23,723 | 8,491 | 47,970 |

| Sebastopol | 7,379 | 6,509 | 72 | 60 | 120 | 19 | 298 | 301 | 885 |

| Sonoma | 10,648 | 9,242 | 52 | 56 | 300 | 23 | 711 | 264 | 1,634 |

| Windsor | 26,801 | 19,798 | 227 | 594 | 810 | 51 | 4,052 | 1,269 | 8,511 |

places | Population | American | American | Islander | races | more races | or Latino (of any race) | ||

| Bloomfield | 345 | 282 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 52 | 7 | 62 |

| Bodega | 220 | 209 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 9 |

| Bodega Bay | 1,077 | 951 | 2 | 4 | 33 | 4 | 49 | 34 | 126 |

| Boyes Hot Springs | 6,656 | 4,505 | 48 | 91 | 84 | 9 | 1,674 | 245 | 3,270 |

| Carmet | 47 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Cazadero | 354 | 318 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 18 | 23 |

| El Verano | 4,123 | 3,054 | 22 | 22 | 101 | 12 | 717 | 195 | 1,559 |

| Eldridge | 1,233 | 988 | 10 | 3 | 36 | 6 | 144 | 46 | 325 |

| Fetters Hot Springs-Agua Caliente | 4,144 | 2,926 | 25 | 39 | 68 | 8 | 895 | 183 | 1,925 |

| Forestville | 3,293 | 2,914 | 32 | 36 | 53 | 6 | 153 | 99 | 406 |

| Fulton | 541 | 349 | 3 | 12 | 11 | 1 | 149 | 16 | 186 |

| Geyserville | 862 | 609 | 5 | 7 | 14 | 0 | 192 | 35 | 328 |

| Glen Ellen | 784 | 693 | 3 | 9 | 16 | 3 | 18 | 42 | 67 |

| Graton | 1,707 | 1,402 | 10 | 29 | 25 | 3 | 144 | 94 | 322 |

| Guerneville | 4,534 | 3,926 | 31 | 68 | 47 | 12 | 226 | 224 | 553 |

| Jenner | 136 | 125 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 8 |

| Kenwood | 1,028 | 930 | 1 | 1 | 23 | 2 | 45 | 26 | 79 |

| Larkfield-Wikiup | 8,884 | 7,042 | 81 | 168 | 292 | 19 | 878 | 404 | 1,979 |

| Monte Rio | 1,152 | 1,047 | 10 | 6 | 11 | 1 | 16 | 61 | 79 |

| Occidental | 1,115 | 992 | 7 | 7 | 31 | 0 | 23 | 55 | 81 |

| Penngrove | 2,522 | 2,212 | 19 | 24 | 54 | 2 | 112 | 99 | 292 |

| Roseland | 6,325 | 3,235 | 130 | 224 | 276 | 15 | 2,078 | 367 | 3,773 |

| Salmon Creek | 86 | 86 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sea Ranch | 1,305 | 1,220 | 15 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 37 | 20 | 117 |

| Sereno del Mar | 126 | 118 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Temelec | 1,441 | 1,376 | 4 | 4 | 31 | 5 | 5 | 16 | 68 |

| Timber Cove | 164 | 152 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 |

| Valley Ford | 147 | 105 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 8 | 52 |

unincorporated areas | Population | American | American | Islander | races | more races | or Latino (of any race) | ||

| All others not CDPs (combined) | 90,835 | 76,431 | 930 | 1,008 | 1,871 | 183 | 7,375 | 3,037 | 16,303 |

2000

At the 2000 census,[55] there were 458,614 people, 172,403 households, and 112,406 families in Sonoma County. The population density was 291/sq mi (112/km2). There were 183,153 housing units at an average density of 116/sq mi (45/km2).

Of the 172,403 households, 50.3% were married couples living together, 34.8% were non-families, and 10.4% had a female householder with no husband present. 31.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 25.7% were individuals, and 10.0% were 65 years of age or older living alone. The average household size was 2.60, and the average family size was 3.12.

The median age was 38 years. 24.5% were under 18, 8.8% from 18 to 24, 29.2% from 25 to 44, 24.9% from 45 to 64, and 12.6% were 65 years of age or older. For every 100 females there were 97 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94 males.

The median household income was $53,076, and the median family income was $61,921. Males had a median income of $42,035, females $32,022. The per capita income for the county was $25,724. About 4.7% of families and 8.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 8.4% of those under age 18 and 5.7% of those age 65 or over.

Metropolitan Statistical Area

The United States Office of Management and Budget has designated Sonoma County as the Santa Rosa-Petaluma, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area.[56] The United States Census Bureau ranked the Santa Rosa-Petaluma, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area as the 105th most populous metropolitan statistical area of the United States as of July 1, 2012.[57]

The Office of Management and Budget has further designated the Santa Rosa-Petaluma, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area as a component of the more extensive San Jose-San Francisco-Oakland, CA Combined Statistical Area,[56] the 5th most populous combined statistical area and primary statistical area of the United States as of July 1, 2012.[57][58]

Government

Sonoma County's governing board and legislative body is the five-member Sonoma County Board of Supervisors.[59] Supervisors are elected by district[60] at the Consolidated Primary Election, and serve for four years. The Supervisors also sit as directors of several local jurisdictions, such as Sonoma Water,[61] and the Agricultural Preservation & Open Space District.[62]

The current supervisors (as of January 2020) are:

- District 1: Susan Gorin,

- District 2: David Rabbitt,

- District 3: Shirlee Zane,

- District 4: James Gore, and

- District 5: Lynda Hopkins.[63]

The Supervisors appoint the members of 59 boards, commissions, and committees.[64]

The County Administrator[65] is the county's chief executive officer, reporting to the Board of Supervisors. The administrator manages the county's departments, such as the regional parks department.

On December 15, 2009, the Board announced[66] the appointment of Veronica Ferguson to be the first woman County Administrator. She assumed office on February 1, 2010.

On May 1, 2014, the county launched a public utility named Sonoma Clean Power.[67] This utility was created under the guidelines of Community Choice Aggregation.

State and federal representation

Sonoma County is split between California's 2nd and 5th congressional districts, represented by Jared Huffman (D–San Rafael) and Mike Thompson (D–St. Helena), respectively.[68]

In the California State Assembly, Sonoma County is split between the 2nd, 4th, and 10th districts, which are held by Democrat Jim Wood, Democrat Cecilia Aguiar-Curry, and Democrat Marc Levine, respectively.[69] In the California State Senate, the county is split between the 2nd Senate District, represented by Democrat Mike McGuire, and the 3rd Senate District, represented by Democrat Bill Dodd.

Law enforcement

The Sonoma County Sheriff's Department is the law enforcement agency for the unincorporated area of the county. It also contracts to provide the police forces of the City of Sonoma and the Town of Windsor. The department has more than 1,000 employees, including more than 275 Deputy Sheriffs, in four bureaus. More than 300 Correctional Officers and staff work in two jail facilities; Main Area Detention Facility and the North County Detention Facility, with a total daily population of nearly 1,200 inmates.[70] Police shootings in 2007 led to calls for an independent civilian police review board;[71] which was established in 2015.[72]

Economy

Forbes Magazine ranked the Santa Rosa metropolitan area—essentially the entire county—185th out of 200, on its 2007 list of Best Places For Business And Careers.[73] It was second on the list five years before. Sonoma County was downgraded because of an increase in the cost of doing business, and reduced job growth, both blamed on increases in the cost of housing.

Winemaking—both the growing of the grapes and their vinting—is an important part of the economic and cultural life of Sonoma County. In 2004, growers harvested 165,783 short tons (150,396 t)s) of wine grapes worth US$310 million. In 2006 the Sonoma County grape harvest amounted to over 185,000 tons, exceeding Napa County's harvest by more than 30 percent.[74] About 80 percent of non-pasture agricultural land in the county is for growing wine grapes—58,280.4 acres (235.852 km2) in 2014 of vineyards, with over 1100 growers. The most common varieties planted are Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Pinot noir, though the area is also known for its Merlot and Zinfandel.[75]

Sonoma County is home to more than 350 wineries with eleven distinct and two shared American Viticultural Areas, including the Sonoma Valley AVA, Russian River Valley AVA, Alexander Valley AVA, Bennett Valley AVA and Dry Creek Valley AVA, the last of which is known for the production of high-quality Zinfandels.

Politics

For most of the 20th century, Sonoma County was a Republican stronghold in presidential elections. From 1880 until 1988, the only Democrats to carry Sonoma were Winfield Scott Hancock in 1880, Grover Cleveland in 1888 and 1892, Woodrow Wilson in 1912, Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 and 1936, and Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964.[76] Like the rest of the Bay Area, it has since become a Democratic stronghold.

The last Republican to win a majority in the county was Ronald Reagan in 1984, and the last Republican to represent a significant part of the county in Congress was Representative Donald H. Clausen, who left office in January 1983.

| Year | GOP | DEM | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 23.0% 61,825 | 74.5% 199,938 | 2.4% 6,554 |

| 2016 | 22.0% 51,408 | 68.8% 160,435 | 9.2% 21,460 |

| 2012 | 25.3% 54,784 | 71.0% 153,942 | 3.8% 8,139 |

| 2008 | 24.0% 55,127 | 73.6% 168,888 | 2.3% 5,336 |

| 2004 | 30.9% 68,204 | 67.2% 148,261 | 1.9% 4,225 |

| 2000 | 32.3% 63,529 | 59.5% 117,295 | 8.2% 16,182 |

| 1996 | 29.5% 53,555 | 55.6% 100,738 | 14.9% 27,004 |

| 1992 | 24.1% 47,619 | 52.8% 104,334 | 23.1% 45,738 |

| 1988 | 41.9% 67,725 | 56.5% 91,262 | 1.6% 2,596 |

| 1984 | 51.1% 76,447 | 47.6% 71,295 | 1.3% 1,915 |

| 1980 | 48.2% 60,722 | 36.2% 45,596 | 15.6% 19,667 |

| 1976 | 47.7% 50,555 | 47.5% 50,353 | 4.8% 5,044 |

| 1972 | 54.7% 57,697 | 41.5% 43,746 | 3.8% 3,991 |

| 1968 | 48.8% 38,088 | 43.0% 33,587 | 8.2% 6,384 |

| 1964 | 38.4% 27,677 | 61.5% 44,354 | 0.2% 105 |

| 1960 | 54.1% 34,641 | 45.5% 29,147 | 0.4% 244 |

| 1956 | 61.9% 33,659 | 37.9% 20,616 | 0.2% 86 |

| 1952 | 66.1% 35,605 | 32.8% 17,675 | 1.1% 594 |

| 1948 | 55.2% 22,077 | 40.1% 16,026 | 4.7% 1,881 |

| 1944 | 50.4% 16,309 | 49.3% 15,949 | 0.3% 111 |

| 1940 | 51.9% 16,819 | 47.0% 15,230 | 1.0% 330 |

| 1936 | 39.0% 11,185 | 60.2% 17,273 | 0.9% 248 |

| 1932 | 35.7% 9,161 | 61.1% 15,686 | 3.2% 822 |

| 1928 | 59.7% 12,891 | 39.4% 8,506 | 0.9% 194 |

| 1924 | 56.0% 9,535 | 10.4% 1,767 | 33.6% 5,726 |

| 1920 | 66.9% 10,377 | 26.2% 4,070 | 6.9% 1,065 |

| 1916 | 50.4% 9,733 | 43.4% 8,377 | 6.3% 1,214 |

| 1912 | 0.2% 32 | 45.8% 6,500 | 54.0% 7,667[note 4] |

| 1908 | 57.5% 5,427 | 33.6% 3,168 | 8.9% 844 |

| 1904 | 61.6% 5,269 | 32.9% 2,816 | 5.4% 463 |

| 1900 | 54.0% 4,381 | 43.4% 3,517 | 2.6% 209 |

| 1896 | 51.9% 4,053 | 46.0% 3,595 | 2.2% 168 |

| 1892 | 43.4% 3,016 | 49.7% 3,451 | 7.0% 483 |

| 1888 | 46.9% 3,293 | 48.4% 3,394 | 4.6% 324 |

| 1884 | 49.4% 3,044 | 47.7% 2,944 | 2.7% 172 |

| 1880 | 45.4% 2,290 | 52.1% 2,628 | 2.4% 122 |

| Year | GOP | DEM |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 27.7% 58,338 | 72.3% 152,040 |

| 2014 | 25.2% 36,249 | 74.8% 107,328 |

| 2010 | 30.1% 55,472 | 64.7% 119,079 |

| 2006 | 47.0% 81,608 | 44.6% 77,392 |

| 2003 | 35.0% 54,651 | 40.7% 63,588 |

| 2002 | 29.9% 43,408 | 50.4% 73,079 |

| 1998 | 29.0% 46,616 | 64.3% 103,235 |

| 1994 | 45.7% 73,234 | 49.7% 79,720 |

| 1990 | 38.6% 54,706 | 55.8% 79,093 |

| 1986 | 59.4% 75,003 | 37.9% 47,859 |

| 1982 | 45.1% 55,968 | 51.2% 63,542 |

| 1978 | 35.9% 37,584 | 54.3% 56,920 |

| 1974 | 48.0% 40,339 | 48.5% 40,756 |

| 1970 | 58.6% 44,823 | 39.2% 29,953 |

| 1966 | 60.7% 41,516 | 39.3% 26,898 |

| 1962 | 49.7% 29,647 | 49.2% 29,373 |

On November 4, 2008, Sonoma County voted 66.4% against Proposition 8 which amended the California Constitution to ban same-sex marriages.

According to the California Secretary of State, as of February 2019, there are 277,665 registered voters in Sonoma County.[80] Of those, 143,054 (51.5%) are registered Democratic, 49,386 (17.8%) are registered Republican, and 70,244 (25.3%) declined to state a political party. Every city, town, and the unincorporated areas of Sonoma County have more registered Democrats than Republicans.

Voter registration statistics

| Population and registered voters | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total population[3] | 502,146 | |

| Registered voters[81][note 5] | 261,706 | 54.7% |

| Democratic[81] | 134,896 | 51.5% |

| Republican[81] | 56,428 | 21.6% |

| Democratic–Republican spread[81] | +78,468 | +29.9% |

| Independent[81] | 6,619 | 2.5% |

| Green[81] | 4,640 | 1.8% |

| Libertarian[81] | 1,833 | 0.7% |

| Peace and Freedom[81] | 792 | 0.3% |

| Americans Elect[81] | 3 | 0.0% |

| Other[81] | 829 | 0.3% |

| No party preference[81] | 55,666 | 21.3% |

Cities by population and voter registration

| Cities by population and voter registration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Population[40] | Registered voters[81] [note 5] |

Democratic[81] | Republican[81] | D–R spread[81] | Other[81] | No party preference[81] |

| Cloverdale | 8,390 | 51.8% | 49.1% | 24.7% | +24.4% | 7.9% | 21.1% |

| Cotati | 7,154 | 57.4% | 52.8% | 17.8% | +35.0% | 10.3% | 22.4% |

| Healdsburg | 11,161 | 56.5% | 52.6% | 21.7% | +30.9% | 7.5% | 20.6% |

| Petaluma | 57,265 | 57.5% | 52.3% | 20.5% | +31.8% | 7.8% | 22.0% |

| Rohnert Park | 40,741 | 50.1% | 49.6% | 21.3% | +28.3% | 8.8% | 23.2% |

| Santa Rosa | 164,976 | 50.9% | 52.1% | 21.4% | +30.7% | 7.7% | 21.4% |

| Sebastopol | 7,359 | 69.6% | 61.4% | 11.4% | +50.0% | 9.8% | 19.5% |

| Sonoma | 10,430 | 65.0% | 51.2% | 22.8% | +28.4% | 8.1% | 20.8% |

| Windsor | 26,229 | 54.4% | 46.6% | 27.5% | +19.1% | 7.5% | 21.1% |

Education

Higher education

- Empire College, Santa Rosa

- Golden Gate University (Rohnert Park satellite of Walnut Creek Campus)

- Santa Rosa Junior College

- Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park

- University of San Francisco (Santa Rosa Campus)

The educational system of Sonoma County is similar to that of other counties in California, with a large number of independent districts.

Library system

The Sonoma County Library system offers a Central Library in downtown Santa Rosa, plus ten branch libraries and two rural stations. More than half of Sonoma County's residents have library cards, and borrow more than 2.5 million items a year. The Library's website and catalog receive over 200,000 visits annually. Staff answer nearly half a million reference questions annually for individuals, businesses and government agencies. During a typical school year over 750 classes, more than half the county total, either visit a library or are visited by a children's librarian. The Library operates an adult literacy program, training volunteers to tutor individuals who lack basic reading ability. Computer terminals are made available for free Internet access.[82]

Museums

- The Pacific Coast Air Museum is on the southeast corner of the Charles M. Schulz Sonoma County Airport, next to the airplane hangar used in the 1963 Hollywood all-star comedy movie, It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

- Charles M. Schulz Museum , Santa Rosa

- Sonoma County Museum , Santa Rosa

- Luther Burbank Home and Gardens , Santa Rosa

- Healdsburg Museum & Historical Society , Healdsburg

- Hand Fan Museum of Healdsburg , Healdsburg

- Petaluma Historical Library and Museum , Petaluma

- Wildlife & Natural Science Museum Petaluma

- Military Antiques & Museum Petaluma

- Sonoma Valley Museum of Art ,Sonoma

- Depot Park Museum ,Sonoma

- West County Museum ,Sebastopol

- History Museum (aka The Gould-Shaw House Museum), Cloverdale

- California Indian Museum and Cultural Center , Santa Rosa

- Cotati Museum , Cotati

Places of interest

- Hood Mountain Regional Park

- Safari West

- Sonoma Raceway

- Sonoma Coast State Beach,[83] including Arched Rock Beach, Gleason Beach and Goat Rock Beach.

- Spring Lake Regional Park

- Sugarloaf Ridge State Park

- Bodega Bay

- Doran Regional Park

- Fort Ross, former Russian fur trade outpost

- Luther Burbank Home and Gardens

- Luther Burbank Gold Ridge Experiment Farm

- Quarryhill Botanic Garden

- Lake Sonoma

- Tolay Lake Regional Park

- Jack London State Historic Park, author Jack London's Beauty Ranch, in Glen Ellen

- Rancho Petaluma Adobe

- Mission San Francisco Solano, across from Sonoma Plaza

- Armstrong Redwoods State Reserve

- Stillwater Cove

- Sonoma TrainTown Railroad

Populated places

Incorporated

Sonoma County has nine incorporated municipalities.

| Incorporated communities | Population[84] | Incorporation Date[85] |

|---|---|---|

| City of Cloverdale | 8,618 | February 28, 1872 |

| City of Cotati | 7,265 | July 16, 1963 |

| City of Healdsburg | 11,254 | February 20, 1867 |

| City of Petaluma | 57,941 | April 12, 1858 |

| City of Rohnert Park | 40,971 | August 28, 1962 |

| City of Santa Rosa | 167,815 | March 26, 1868 |

| City of Sebastopol | 7,379 | June 13, 1902 |

| City of Sonoma | 10,648 | September 3, 1883 |

| Town of Windsor | 26,801 | July 1, 1992 |

Unincorporated

The county also includes the following populated places which are not incorporated:

Census-designated places

- Bloomfield

- Bodega

- Bodega Bay

- Boyes Hot Springs

- Carmet

- Cazadero

- El Verano

- Eldridge

- Fetters Hot Springs-Agua Caliente

- Forestville

- Fulton

- Geyserville

- Glen Ellen

- Graton

- Guerneville

- Jenner

- Kenwood

- Larkfield-Wikiup

- Monte Rio

- Occidental

- Penngrove

- Roseland

- Salmon Creek

- Sea Ranch

- Serena del Mar

- Temelec

- Timber Cove

- Valley Ford

Other unincorporated places

- Annapolis

- Asti

- Bodega Harbor

- Bridgehaven

- Buena Vista

- Cadwell

- Camp Meeker

- Carneros

- Cozzens Corners

- Cunningham

- Diamond A Ranch

- Duncans Mills

- El Bonita

- Forest Hills

- Freestone

- The Geysers

- Guernewood Park

- Hacienda

- Hessel

- Hilton

- Hollydale

- Jimtown

- Kellogg

- Knowles Corner

- Korbel

- Lakeville

- Lytton

- Mark West

- Mark West Springs

- Mercuryville

- Mesa Grande

- Mirabel Heights

- Mirabel Park

- Mission Highlands

- Monte Cristo

- Montesano

- Noel Heights

- Northwood

- Oakmont

- Odd Fellows Park

- Rancho Abajo

- Rio Dell

- Rio Nido

- Rolands

- Russian River Terrace

- Schellville

- Soda Springs

- Stewarts Point

- Summerhome Park

- Two Rock

- Vacation Beach

- Venado

- Villa Grande

- Vineburg

Former townships

At the time of its formation, the county comprised four civil townships. It was restructured several times, and by 1880 was made up of 14 townships:[86]

- Analy

- Bodega

- Cloverdale

- Knight's Valley

- Mendocino

- Ocean

- Petaluma

- Redwood

- Russian River

- Salt Point

- Santa Rosa

- Sonoma

- Vallejo

- Washington

Population ranking

The population ranking of the following table is based on the 2010 census of Sonoma County.[87]

† county seat

| Rank | City/Town/etc. | Municipal type | Population (2010 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | † Santa Rosa | City | 167,815 |

| 2 | Petaluma | City | 57,941 |

| 3 | Rohnert Park | City | 40,971 |

| 4 | Windsor | Town | 26,801 |

| 5 | Healdsburg | City | 11,254 |

| 6 | Sonoma | City | 10,648 |

| 7 | Larkfield-Wikiup | CDP | 8,884 |

| 8 | Cloverdale | City | 8,618 |

| 9 | Sebastopol | City | 7,379 |

| 10 | Cotati | City | 7,265 |

| 11 | Boyes Hot Springs | CDP | 6,656 |

| 12 | Roseland | CDP | 6,325 |

| 13 | Guerneville | CDP | 4,534 |

| 14 | Fetters Hot Springs-Agua Caliente | CDP | 4,144 |

| 15 | El Verano | CDP | 4,123 |

| 16 | Forestville | CDP | 3,293 |

| 17 | Penngrove | CDP | 2,522 |

| 18 | Graton | CDP | 1,707 |

| 19 | Temelec | CDP | 1,441 |

| 20 | Sea Ranch | CDP | 1,305 |

| 21 | Eldridge | CDP | 1,233 |

| 22 | Monte Rio | CDP | 1,152 |

| 23 | Occidental | CDP | 1,115 |

| 24 | Bodega Bay | CDP | 1,077 |

| 25 | Kenwood | CDP | 1,028 |

| 26 | Geyserville | CDP | 862 |

| 27 | Glen Ellen | CDP | 784 |

| 28 | Fulton | CDP | 541 |

| 29 | Cazadero | CDP | 354 |

| 30 | Bloomfield | CDP | 345 |

| 31 | Bodega | CDP | 220 |

| 32 | Timber Cove | CDP | 164 |

| 33 | Valley Ford | CDP | 147 |

| 34 | Jenner | CDP | 136 |

| 35 | Sereno del Mar | CDP | 126 |

| 36 | Salmon Creek | CDP | 86 |

| 37 | Stewarts Point Rancheria[88] | AIAN | 78 |

| 38 | Carmet | CDP | 47 |

In popular culture

Film

Due to the varied scenery in Sonoma County and proximity to the city of San Francisco, a large number of motion pictures have been filmed using venues within the county. Some of the earliest U.S. filmmaking occurred in Sonoma County, including Salomy Jane (1914) and one of Broncho Billy Anderson's 1915 Westerns.

Many of these films are classics in American cinematography, such as the 1947 film The Farmer's Daughter (starring Joseph Cotten and Loretta Young) and two Alfred Hitchcock films, Shadow of a Doubt of 1943, filmed and set in Santa Rosa, and The Birds of 1963, filmed largely in Bodega Bay and Bodega. Many other modern classics have used Sonoma County as a filming venue, including American Graffiti, filmed largely in Petaluma.

Other films produced partially in Sonoma County include:

|

Sonoma County

Cloverdale

Glen Ellen

|

Petaluma

Russian River

Santa Rosa

Sebastopol

Sonoma

|

Other

Bliss, the default computer wallpaper of Microsoft's Windows XP operating system, is a photograph of a green hill and blue sky with clouds in Sonoma County. Taken in 1996 by Charles O'Rear, it is the most viewed photo in the world.[89]

See also

Notes

- Only larceny-theft cases involving property over $400 in value are reported as property crimes.

- Other = Some other race + Two or more races

- Native American = Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander + American Indian or Alaska Native

- This total comprised 5,806 votes for Progressive Theodore Roosevelt (who was official Republican nominee in California), 1,494 votes for Socialist Eugene V. Debs and 367 votes for Prohibition Party nominee Eugene W. Chafin.

- Percentage of registered voters with respect to total population. Percentages of party members with respect to registered voters follow.

References

- "Chronology". California State Association of Counties. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- "Cobb Mountain-Southwest Peak". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- "American FactFinder". Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District". Sonoma County. Archived from the original on December 31, 2006. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- "Sonoma County Indicators: 2007" (PDF). Sonoma County. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved July 17, 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Sonoma County Flood Control and Water Conservation District: History". Sonoma County Water Agency. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009.

- "California County History". CSAC.org. California State Association of Counties. 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- "Sonoma County History". Calarchives4u.com. Archived from the original on March 19, 2014. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- "History of Sonoma County". ap.net. AccessPort. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012.

- "Sonoma County General Plan – Public Safety Element". October 11, 2008. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008.

- Jones, Kevin L. (October 11, 2017). "Bernie Krause's Equipment, Decades of Musical Memorabilia Lost in Fires". KQED Arts. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- SFGATE, Amanda Bartlett (September 28, 2020). "Everything you need to know about the Glass Fire". SFGATE. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- Gudde, Erwin Gustav; Bright, William (1998). California Place Names: The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographical Names (Second ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. g. 370. ISBN 0-520-21316-5.

- May, James (May 19, 2003). "Why Graton is trying to get into gaming". Indian Country Today. Retrieved January 25, 2009.

- Hanna, Phil Townsend (1951). The Dictionary of California Land Names. Los Angeles: The Automobile Club of Southern California. p. 311.

- Alfred Louis Kroeber (1976). Handbook of the Indians of California. New York City, N.Y.: Dover Publications.

- Alfred L. Kroeber, AAE 29:354 [1932]

- Jesse O. Sawyer (1980). "The Naming of Sonoma". University of California, Berkeley: The Bear Flag News.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Annadel State Park". Parks and Recreation in Sonoma County. Archived from the original on October 11, 1997.

- "Sonoma County Climatic Zones" (PDF). University of California Cooperative Extension. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2007. Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- Forrey, Rip. "Climate data for various locations in Sonoma, Napa, Mendocino, Lake and Marin counties, California" (PDF). University of California Cooperative Extension Sonoma County. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2007. Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- Freedman, Wayne (April 5, 2006). "Rainiest Town In The Bay Area Up For Sale". KGO-TV News. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- "Subsection M261Be Konocti Flows". U.S. Forest Service. Archived from the original on September 22, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- Carolyn Jones (May 27, 2010). "Bay Area beaches grade well for safe swimming". San Francisco Chronicle.

- "The Ecology of the Laguna de Santa Rosa". lagunafoundation.org. Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- "Ecology". lagunadesantarosa.org. Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007.

- "Damage to Creeks, Water Supply Analyzed After Sonoma County Fires". www.govtech.com. 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- "Fisheries Enhancement Program". Sonoma County Water Agency. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009.

- Marin, Solono, Sonoma and Contra Costa Counties' borders come to a common point approx. 6 miles into San Francisco Bay. Thus, Contra Costa County is an adjacent county. Hittell, Theodore Henry (1876). The codes and statutes of the State of California. A. L. Bancroft. p. 515. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

3955.

- "California Codes, Government Codes, section 23149". Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- "CityBus". City of Santa Rosa. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- "About SMART". sonomamarintrain.org. September 26, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- Codoni, Fred; Trimble, Paul Castelhun (2006). Northwestern Pacific Railroad. Arcadia Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 0738531219.

- "Sonoma Valley Railroads". Sonoma Valley. LocalWiki. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- "West County and Joe Rodota Trails". Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- "Smart Train Service Between Marin, Sonoma County To Start Aug. 25". KPIX 5 CBS San Francisco. CBS Broadcasting, Inc. August 17, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B02001. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- Office of the Attorney General, Department of Justice, State of California. Table 11: Crimes – 2009 Archived December 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States, 2012, Table 8 (California). Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B03003. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19301. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19013. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19113. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B01003. U.S. Census website . Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- Data unavailable

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- "2010 Census P.L. 94-171 Summary File Data". United States Census Bureau.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- "OMB Bulletin No. 13-01: Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas" (PDF). United States Office of Management and Budget. February 28, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". 2012 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2013. Archived from the original (CSV) on April 1, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- "Table 2. Annual Estimates of the Population of Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". 2012 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2013. Archived from the original (CSV) on May 17, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- "Board of Supervisors". Sonoma County. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- "Supervisorial Districts". sonoma-county.org. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- "Sonoma County Water Agency". scwa.org. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- "Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District". sonomaopenspace.org. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- "Board of Supervisors". County of Sonoma. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- "Boards, Commissions, Committees & Task Forces". sonoma-county.org. June 29, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- "County Administrators Office". Departments and Agencies. Sonoma County. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014.

- "Press Release: Supervisors Announce New County Administrator" (PDF). Sonoma County. December 15, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - GNECKOW, ERIC (May 1, 2014). "Sonoma Clean Power flips switch for first customers". The North Bay Business Journal. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- "California's 5th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- "Members Assembly". State of California. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- "Sheriff's Department Overview". Sonoma County Sheriff's Office. April 19, 2002. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- Santa Rosa Press Democrat, 3/30/07: Fatal police shootings rekindle review debate/Recent cases raise decade-old concerns over agencies' abilities to investigate each other

- "THE HISTORY OF THE INDEPENDENT OFFICE OF LAW ENFORCEMENTREVIEW AND OUTREACH (IOLERO)" (PDF). Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- Kurt Badenhausen (April 5, 2007). "Best Places For Business And Careers". Forbes. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- "2006 Sonoma County grape harvest statistics: Sonoma County Vintners association". Sonoma County Vintner. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017.

- "Sonoma County Crop Report 2014" (PDF). www.sonoma-county.org/agcomm. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- Menendez, Albert J.; The Geography of Presidential Elections in the United States, 1868–2004, pp. 152–155 ISBN 0786422173

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- "Current Election Results". Sonoma County Registrar of Voters. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- "Final Results for Consolidated General Election – November 4, 2014". Sonoma County Registrar of Voters. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- https://elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov/ror/ror-odd-year-2019/politicalsub.pdf

- California Secretary of State. February 10, 2013 – Report of Registration Archived July 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- "California Library Statistics Archived February 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine" California Library Statistics – 2011–2012 Retrieved February 10, 2015

- "Sonoma County Regional Parks". parks.sonomacounty.ca.gov. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- "Places in California listed alphabetically". U.S. Census. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on February 21, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- Munro-Fraser, J. P. (1880). History of Sonoma County: Including Its Geology, Topography, Mountains, Valleys and Streams ... Alley, Bowen & Co. OCLC 06846293.

- "2010 U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- https://www.census.gov/2010census/popmap/ipmtext.php?fl=3985%5B%5D

- Heisler, Yoni (July 23, 2015). "The Most Viewed Photo in the History of the World". BGR. Retrieved July 15, 2018.

Further reading

- An Illustrated History of Sonoma County, California. Lewis Publishing Company. 1889. OCLC 04107195.

- California Gazetteer. Wilmington: American Historical Publications. 1985. ISBN 0937862754. OCLC 12372425.

- Finley, Ernest L. (1937). History of Sonoma County, California: Its People and Its Resources. Santa Rosa: Press Democrat Pub. Co. OCLC 21868591.

- Gille, Frank H. ed. (1998). The Encyclopedia of California. St. Clair Shores: Somerset Publishers, Inc. ISBN 9780403098705. OCLC 894506127.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Gregory, Thomas Jefferson (1911). History of Sonoma County, California, with Biographical Sketches of the Leading Men and Women of the County, Who Have Been Identified with Its Growth and Development from the Early Days to the Present Time. Los Angeles: Historic Record Company. OCLC 04387962.

- Hansen, Harvey J.; Miller, Jeanne Thurlow (1962). Wild Oats in Eden; Sonoma County in the 19th Century. Santa Rosa. OCLC 01847987.

- Historical Atlas Maps of Sonoma County, California. Oakland: Thos. H. Thompson & Co. 1877. OCLC 06166297.

- Munro-Fraser, J. P. (1880). History of Sonoma County: Including Its Geology, Topography, Mountains, Valleys and Streams ... Alley, Bowen & Co. OCLC 06846293.

- Taber, George M. (2005). Judgment of Paris: California vs. France and the Historic 1976 Paris Tasting that Revolutionized Wine. NY: Scribner. ISBN 9780743247511. OCLC 58843337.

- Thompson, Robert A. (1877). Historical and Descriptive Sketch of Sonoma County, California. L.H. Everts & Co. p. 1. OCLC 06840554.

- Thompson, Robert A. (1884). Central Sonoma: A Brief Description of the Township and Town of Santa Rosa, Sonoma County, California, Its Climate and Resources. W.M. Hinton & Company. OCLC 11855702.

- Thompson, Robert A. (1896). Conquest of California: Capture of Sonoma by Bear Flag Men June 14, 1846. Raising of the American Flag in Monterey by Commodore John D. Sloat, July 7, 1846. Sonoma Democrat. OCLC 02540771.

- Thompson, Robert A. (1896). The Russian Settlement in California. Sonoma Democrat Publishing Company. OCLC 15538413.

- Tuomey, Honoria (1926). History of Sonoma County, California. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Pub. Co. OCLC 12074234., Volume one, Volume two

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sonoma County, California. |