International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

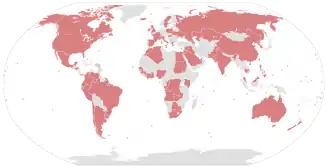

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) is an independent, Washington, D.C.-based international network of more than 200 investigative journalists and 100 media organizations in over 70 countries.[2] Launched in 1997 by the Center for Public Integrity,[3] ICIJ was spun off in February 2017 into a fully independent organization working on "issues such as "cross-border crime, corruption, and the accountability of power."[1][4] The ICIJ has exposed smuggling and tax evasion by multinational tobacco companies (2000),[5] "by organized crime syndicates; investigated private military cartels, asbestos companies,[6] and climate change lobbyists; and broke new ground by publicizing details of Iraq and Afghanistan war contracts."[1][4][7]

| |

| Abbreviation | ICIJ |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1997 |

| Location | |

Director | Gerard Ryle |

| Sheila Coronel (chair), Reginald Chua, Alex Papachristou, Rhona Murphy, Steven King and Gerard Ryle (non-executive director)[1] | |

Main organ | The Global Muckraker |

| Website | ICIJ |

The Panama Papers, was a collaboration of more than 100 media partners,[8] including members of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project,[9] with journalists who worked on the data, culminating in a partial release on 3 April 2016, garnering global media attention.[10][11] The set of 11.5 million confidential financial and legal documents from the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca included detailed information on more than 14,000 clients and more than 214,000 offshore entities, including the identities of shareholders and directors including noted personalities and heads of state[12]—government officials, close relatives and close associates of various heads of government of more than 40 other countries.[13][12][14] The German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung first received the released data from an anonymous source in 2015.[12] After working on the Mossack Fonseca documents for a year, ICIJ director Gerard Ryle described how the offshore firm had "helped companies and individuals with tax havens, including those that have been sanctioned by the U.S. and UK for dealing with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad."[15]

History

In 1997, the Center for Public Integrity began "assembling the world's first working network of premier investigative reporters." By 2000 the ICIJ consisted of 75 world-class investigative reporters in 39 countries."[16]:11

In early November 2014, the ICIJ's Luxembourg Leaks investigation revealed that Luxembourg under Jean-Claude Juncker's premiership had turned into a major European centre of corporate tax avoidance.[17]

In February 2015, the ICIJ website released information about bank accounts in Switzerland under the title Swiss Leaks: Murky Cash Sheltered by Bank Secrecy, which published information on 100,000 clients and their accounts at HSBC.

In February 2017, ICIJ was spun off into a fully independent organisation, which is now governed by three committees: a traditional board of directors with a fiduciary role; an Advisory Committee made of supporters; and an ICIJ Network Committee.[2]

ICIJ was granted nonprofit status from US tax authorities in July the same year.[2]

In 2017, the ICIJ, the McClatchy Company, and the Miami Herald won the Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting "for the Panama Papers, a series of stories using a collaboration of more than 300 reporters on six continents to expose the hidden infrastructure and global scale of offshore tax havens."[18] In total, the ICIJ won more than 20 awards for the Panama Papers.[19]

Selected reports

Global tobacco industry

From 2008 to 2011, the ICIJ investigated the global tobacco industry, revealing how Philip Morris International and other tobacco companies worked to grow businesses in Russia, Mexico, Uruguay and Indonesia.[20]:23

Offshore banking series

The ICIJ partnered with The Guardian, BBC, Le Monde, the Washington Post, SonntagsZeitung, The Indian Express, Süddeutsche Zeitung and NDR to produce an investigative series on offshore banking.[21][22] They reported on government corruption across the globe, tax avoidance schemes used by wealthy people and the use of secret offshore accounts in Ponzi Schemes.[23]

In June 2011, an ICIJ article revealed how an Australian businessman had helped his clients legally incorporate thousands of offshore shell entitles "some of which later became involved in the international movement of oil, guns and money."[24]

In April 2013, a report (Offshore Leaks) disclosing details of 130,000 offshore accounts some of which conducted international tax fraud.

In early 2014, the ICIJ revealed that relatives of China's political and financial elite were among those using offshore tax havens to conceal wealth.[25]

In July 2019, the Mauritius Leaks showed how Mauritius was being used as one such tax haven.

In January 2020, Luanda Leaks revealed how Angola's richest woman, Isabel dos Santos, used a network of Western advisors to amass a fortune.[26] The investigation exposed two decades of corrupt deals that made dos Santos Africa's wealthiest woman and left oil- and diamond-rich Angola one of the world's poorest countries.[27] The investigation showed how dos Santos and her husband, Sindika Dokolo built their empire taking advantage of many secrecy jurisdictions.[28]

Panama Papers

The Süddeutsche Zeitung received a leaked set of 11.5 million confidential documents from a secret source, created by the Panamanian corporate service provider Mossack Fonseca.[29] The so-called Panama Papers provided detailed information on more than 214,000 offshore companies, including the identities of shareholders and directors which included government officials, close relatives and close associates of various heads of government of more than 40 other countries.[12][14] Because of the leak the prime minister of Iceland, Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, was forced to resign on 5 April 2016.[11] By 4 April 2016 more than "107 media organisations in 76 countries"[30] had participated in analyzing the documents,[15] including BBC Panorama and the UK newspaper, The Guardian.[30] Based on the Panama Paper disclosure, Pakistan Supreme Court constituted the Joint Investigation Team to probe the matter and disqualified the Prime Minister Nawas Sharif on 28 July 2017 to hold any public office for life.

The ICIJ and Süddeutsche Zeitung received the Panama Papers in 2015 and distributed them to about 400 journalists at 107 media organizations[30] in more than 80 countries. The first news reports based on the set, along with 149 of the documents themselves,[29][31][32]

According to The New York Times,[11]

[T]he Panama Papers reveal an industry that flourishes in the gaps and holes of international finance. They make clear that policing offshore banking and tax havens and the rogues who use them cannot be done by any one country alone. Lost tax revenue is one consequence of this hidden system; even more dangerous is its deep damage to democratic rule and regional stability when corrupt politicians have a place to stash stolen national assets out of public view.

Paradise Papers

In 2017, the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung obtained a "cache" of "13.4 million leaked files"[33][34] regarding tax havens, known as the Paradise Papers, related to the Bermuda-based offshore specialist Appleby, "one of the world's largest offshore law firms." The files were shared with them the ICIJ and eventually 95 media outlets."[34] They revealed that many of the tax havens used by Appleby are in the Cayman Islands, which is a British territory that "levies no corporate or personal income tax on money earned outside its jurisdiction."[34][35] The Paradise Papers revealed the "offshore activities of some of the world's most powerful people and companies".[33]

China Cables

In November 2019, the ICIJ revealed classified Chinese government documents leaked by exiled Uighurs, dubbed the China Cables which prove mass surveillance and internment camps of Uighurs and other Muslim minorities in China's Xinjiang province.[36]

FinCEN Files

The FinCEN Files are leaked documents from the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) that describe suspicious financial transactions across multiple global financial institutions.[37]

Data journalism

In the course of the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers investigations, ICIJ was challenged to learn about and implement various technologies to manage international collaboration on terabytes of data – structured and unstructured (e.g. emails, PDFs) – and how to extract meaningful information from this data. Among the technologies used were the Neo4J graphic database management systems and Linkurious to search and visualize the data.[38] The data-intensive projects involved not just veteran investigative journalists, but also demanded data journalists and programmers.

Awards

The ICIJ organized the bi-annual Daniel Pearl Awards for Outstanding International Investigative Reporting. The award is currently not being awarded.[2][39][40][41][42][43]

GuideStar, a nonprofits evaluator, gave the ICIJ a "Gold Seal of Transparency" in 2019.[44]

See also

- European Investigative Collaborations

- Center for Public Integrity (United States)

References

- "About". ICIJ. 6 April 2016. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- "About the ICIJ". ICIJ. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- Vasilyeva, Natalya; Anderson, Mae (3 April 2016). "News Group Claims Huge Trove of Data on Offshore Accounts". The New York Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ICIJ, About the ICIJ

- Beelman, Maud; Campbell, Duncan; Ronderos, Maria Teresa; Schelzig, Erik J. (January 2000), "Major Tobacco Multinational Implicated in Cigarette Smuggling, Tax Evasion, Documents Show", International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

- "Dangers in the Dust" (PDF). International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- "Gerard Ryle". Center for Public Integrity.

- "About the investigation". Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- "ICIJ/OCCRP Panama Papers project yields unprecedented access to high level offshore corruption". www.occrp.org. Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists". ICIJ. April 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- Board, The Editorial (5 April 2016). "The Panama Papers' Sprawling Web of Corruption". New York Times. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- Vasilyeva, Natalya; Anderson, Mae (3 April 2016). "News Group Claims Huge Trove of Data on Offshore Accounts". The New York Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- Garside, Juliette; Pegg, David (6 April 2016). "Panama Papers reveal offshore secrets of China's red nobility: Disclosures show how havens such as British Virgin Islands hide links between big business and relatives of top politician". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- "Panama Papers: The Power Players". International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Epatko, Larisa (4 April 2016). "Here's what we know so far about the leaked Panama papers". PBS. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- "2000 Center for Public Integrity Annual Report" (PDF). Center for Public Integrity. 2000. p. 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- "Luxembourg tax files: how tiny state rubber-stamped tax avoidance on an industrial scale". The Guardian. 5 November 2014.

- "Explanatory Reporting". Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- "ICIJ's Awards". Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- Freudenberg, Nicholas (21 January 2014). Lethal But Legal: Corporations, Consumption, and Protecting Public Health. Oxford University Press. p. 344. ISBN 9780199937196.

- Pitzke, Marc (4 April 2013). "Offshore Leaks: Vast Web of Tax Evasion Exposed". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- "Offshore secrets: what is the Guardian investigation based on?". London: guardian.co.uk. 25 November 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Guevara, Marina Walker; Hager, Nicky; Cabra, Mar; Ryle, Gerard; Menkes, Emily. Who Uses the Offshore World (Report). Secrecy for Sale: Inside the Global Offshore Money Maze. [International Consortium for Investigative Journalists http://www.icij.org]. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- Ryle, Gerard (28 June 2011). "Inside the shell: Drugs, arms and tax scams". Secrecy for sale: inside the global offshore money maze. ICIJ. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- Gerard Ryle (21 January 2014). "China's elite linked to secret offshore entities". ICIJ. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- "Western advisers helped an autocrat's daughter amass and shield a fortune". Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- "Luanda Leaks | Africa's richest woman exploited family ties, shell companies and inside deals". Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- "Explore: How to build a business empire". Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- "DocumentCloud 149 Results Source: Internal documents from Mossack Fonseca (Panama Papers) – Provider: Amazon Technologies / Owner: Perfect Privacy, LLC USA". Center for Public Integrity. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- "Panama Papers: Government announces creation of 'panel of experts'", BBC News, BBC, 7 April 2016, retrieved 7 April 2016

- Obermaier, Frederik; Obermayer, Bastian; Wormer, Vanessa; Jaschensky, Wolfgang (3 April 2016). "About the Panama Papers". Süddeutsche Zeitung. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "The Panama Papers: Data Metholodogy". ICIJ. 3 April 2016. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "ICIJ releases new investigation: the Paradise Papers". International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. 5 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- McIntire, Mike; Chavkin, Sasha; Hamilton, Martha M. (5 November 2017). "Commerce Secretary's Offshore Ties to Putin 'Cronies'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- "'Paradise Papers' documents touch Trump administration". POLITICO. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Shiel, Fergus (23 November 2019). "China Cables,China's Operating Manuals for Mass Internment". International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Donkin, Karissa; Zalac, Frédéric (25 September 2020). "2 shadowy Canadian companies flagged by banks for millions received in suspicious transfers". CBC News. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- Ghosh, Shona (8 November 2017). "How a nerdy Swedish database startup with $80m in funding cracked the Paradise Papers". Business Insider. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "Razzle-Dazzle 'Em Ethics Reform". New York Times. 26 June 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Galvin, Kevin (1996). "Buchanan Campaign Chief Has Military Ties". Associated Press.

- Goldstein, Steve (16 February 1996). "'Outsider' Runs Filled With 'Insider' Advisers". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Center for Public Integrity. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- "The States Get a Poor Report Card". New York Times. 19 March 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- "International Consortium of Investigative Journalists Inc - GuideStar Profile". GuideStar.org. Retrieved 1 January 2020.