Interstate 495 (New York)

Interstate 495 (I-495), commonly known as the Long Island Expressway (LIE), is an auxiliary Interstate Highway in the U.S. state of New York. It is jointly maintained by the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT), the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT), MTA Bridges and Tunnels (MTAB&T), and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ).

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long Island Expressway | ||||

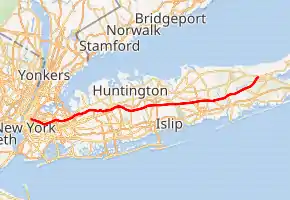

Map of Long Island with I-495 highlighted in red, and service routes in pink | ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Auxiliary route of I-95 | ||||

| Maintained by NYSDOT, NYCDOT, MTAB&T, and PANYNJ | ||||

| Length | 71.02 mi[1] (114.30 km) | |||

| Existed | 1958[2]–present | |||

| Restrictions | No hazardous goods allowed inside the Queens-Midtown Tunnel | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| West end | Queens–Midtown Tunnel portal in Murray Hill | |||

| East end | ||||

| Location | ||||

| Counties | New York, Queens, Nassau, Suffolk | |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

Spanning approximately 71 miles (114 km) along a west–east axis, I-495 traverses Long Island from the western portal of the Queens–Midtown Tunnel in the New York City borough of Manhattan to CR 58 in Riverhead in the east. I-495 intersects with I-295 in Bayside, Queens, through which it connects with I-95. The 2017 route log erroneously shows the section of highway between I-278 in Long Island City and I-678 in Corona as New York State Route 495 (NY 495).[3]

The Long Island Expressway designation, despite being commonly applied to I-495 in full, technically refers to the stretch of highway between Nassau and Suffolk counties. The section from the Queens–Midtown Tunnel to Queens Boulevard is known as the Queens–Midtown Expressway, and the section between Queens Boulevard and the Queens-Nassau county line is known as the Horace Harding Expressway. The service roads which run parallel to either side of the expressway in Queens are signed as Borden Avenue and Queens Midtown Expressway and as Horace Harding Expressway and Horace Harding Boulevard; from the Queens–Nassau line to Sills Road, they are designated as the unsigned New York State Route 906A and New York State Route 906B.

Route description

New York City

The expressway begins at the western portal of the Queens–Midtown Tunnel in the Murray Hill section of Manhattan. The route heads eastward, passing under FDR Drive and the East River as it proceeds through the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority-maintained tunnel to Queens. Once on Long Island, the highway passes through the tunnel's former toll plaza and becomes known as the Queens–Midtown Expressway as it travels through the western portion of the borough. A mile after entering Queens, I-495 meets I-278 (the Brooklyn–Queens Expressway) at exit 17. It continues to the Rego Park neighborhood, where it connects to New York State Route 25 (NY 25, named Queens Boulevard) and becomes the Horace Harding Expressway. I-495 heads northeast through Corona to Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, intersecting both the Grand Central Parkway and the Van Wyck Expressway (I-678) within the park limits. Because the interchanges in this area are close together, the highway employs two sets of collector/distributor roads through this area: one between 69th and 99th Streets, and one between the Grand Central Parkway and I-678.[4]

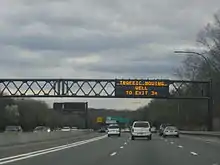

_4.JPG.webp)

The expressway continues east, veering to the southeast to bypass Kissena Park before curving back to the northeast to meet the Clearview Expressway (I-295) at the northern edge of Cunningham Park. Past I-295, I-495 passes by the "Queens Giant", the oldest and tallest tree in the New York metropolitan area. The tree, located just north of I-495 in Alley Pond Park, is visible from the highway's westbound lanes. To the east, the freeway connects to the Cross Island Parkway at exit 31 in the park prior to exiting the New York City limits, crossing into Nassau County, and becoming the Long Island Expressway (LIE).[4]

Although the Long Island Expressway name officially begins outside the New York City border, almost all locals and most signage use "the Long Island Expressway" or "the LIE" to refer the entire length of I-495.[6] The service roads of I-495 are called Borden Avenue and Queens Midtown Expressway between the Brooklyn–Queens Expressway and Queens Boulevard, and "Horace Harding Expressway" between Queens Boulevard and the Nassau County line.[4]

The Horace Harding Expressway section follows the path of Horace Harding Boulevard (also previously called Nassau Boulevard),[7][8] which was named for J. Horace Harding (1863–1929), a finance magnate who directed the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad and the New York Municipal Railways System. Harding used his influence to promote the development of Long Island's roadways, lending strong support to Robert Moses's "great parkway plan". Harding also urged construction of a highway from Queens Boulevard to the Nassau County Line, in order to provide better access to Oakland Country Club, where he was a member. After his death, the boulevard he helped build was named for him. Horace Harding was not related to the former President Warren G. Harding.[9]

Nassau and Suffolk counties

Heading into Nassau County, the expressway sports a High-Occupancy Vehicle Lane (HOV), which begins at exit 33 and runs to central Suffolk County. In its run through Nassau, it is the only major east–west highway that does not interchange with the Meadowbrook or Wantagh state parkways, both of which end to the south at the adjacent Northern State Parkway, which parallels the LIE through the county. The two highways meet three times, although it actually crosses only once at exit 46 near the county line. I-495 does, however, interchange with the Seaford–Oyster Bay Expressway (NY 135) as the east–west parkways do, and often has heavy traffic. In Suffolk County, the LIE continues its eight-lane configuration with the HOV lane to exit 64 (NY 112). At this point, the HOV lane ends and the highway narrows to six lanes; additionally, the concrete Jersey barrier gives way to a wide, grassy median, the asphalt road surface is replaced by a concrete surface, and the expressway is no longer illuminated by streetlights, reflecting the road's location in a more rural area of Long Island.[4]

From NY 112 east, the expressway runs through more rural, woodland areas on its trek towards Riverhead. Exit 68 (William Floyd Parkway) marks the terminus of the service roads, which are fragmented by this point. Exit 70 (CR 111) in Manorville is the last full interchange, as it is the last interchange that allows eastbound traffic on, and the first to allow westbound off. After exit 71 (NY 24 / Nugent Drive), the expressway begins to narrow as it approaches its eastern terminus. Until 2008, just before exit 72 (NY 25), the three eastbound lanes narrowed to two, which in turn narrowed almost immediately to a single lane at exit 73, which lies 800 feet (240 m) east of exit 72. As of 2008, of the two lanes, one lane is designated for exit 72 and the other is for exit 73, which ends the squeeze into a single lane that formerly existed at exit 73. At exit 73, all traffic along the expressway is diverted onto a ramp leading to eastbound CR 58, marking the east end of the route.[4]

HOV restrictions

There is one HOV lane in each direction, in the median of the highway, between exit 32 (Little Neck Parkway), near the Queens-Nassau border, to exit 64 (NY 112), in central Suffolk County.[2] From 6:00 am to 10:00 am and from 3:00 pm to 8:00 pm Monday through Friday, the HOV lanes are limited to buses, motorcycles, and Clean Pass vehicles without occupancy requirement and passenger vehicles with at least two occupants. Trailers and commercial trucks are always prohibited therein.[10]

History

Queens–Midtown Expressway

The Long Island Expressway was constructed in stages over the course of three decades. The first piece, the Queens–Midtown Tunnel linking Manhattan and Queens, was opened to traffic on November 15, 1940.[11] The highway connecting the tunnel to Laurel Hill Boulevard was built around the same time and named the "Midtown Highway".[12][13] The tunnel, the Midtown Highway, and the segment of Laurel Hill Boulevard between the highway and Queens Boulevard all became part of a realigned NY 24 in the mid-1940s.[13][14] Parts of this highway were built on the right of way of a streetcar line that extended from Hunters Point to southern Flushing.[15] In 1945, $60 million in funding was allocated toward a plan to upgrade roads in the New York City area. The plan included building the Queens-Midtown Expressway from the Midtown Tunnel to Queens Boulevard, and the Horace Harding Expressway from Queens Boulevard to the New York City border.[16]

In the early 1950s, work began along what was Borden Avenue as an eastward extension of the Midtown Highway. The road was completed between 48th and 58th Streets, in February 1955,[17] at which point it became known as the "Queens–Midtown Expressway".[18][19] November 5, 1955, was the official opening of the highway's 3.2-mile extension to the junction of Queens Boulevard (NY 24 and NY 25) and Horace Harding Boulevard (NY 25D).[20] However, NY 24 initially remained routed on Laurel Hill Boulevard (by this point upgraded into the Brooklyn–Queens Expressway) and Queens Boulevard.[21]

Horace Harding Expressway and western Nassau

| |

|---|---|

| Location | Long Island |

| Existed | 1958–? |

The LIE was built over much of Horace Harding Boulevard within Eastern Queens and Power House Road within western Nassau County. Prior to the LIE's construction, the route was designated as NY 25D. In May 1951, the New York City Board of Estimate approved the widening of Horace Harding Boulevard and Power House Road to 260 feet, and constructing an expressway in the road's median at a cost of $25 million.[22] The New York State Department of Public Works later modified the highway's route in the vicinity of Little Neck Parkway, near the Queens-Nassau border. At Little Neck Parkway, Horace Harding Boulevard continues northeast and then eastward, whereas the LIE takes a more southerly path. This modification was enacted because of complaints from nearby residents.[23] In 1955, New York State Governor Thomas E. Dewey approved plans for a 64-mile (103 km) extension of the LIE between the Queens-Nassau border and Riverhead in Suffolk County.[24]

Work began on the Horace Harding Expressway in 1955, but soon encountered delays because of weather conditions, construction worker strikes, and difficulties in building across existing roads and swampy land.[25] The highway had been extended east to Parsons Boulevard in Pomonok, Queens, by 1959, where the highway abruptly terminated and barriers funneled traffic onto the service road. Soon after, the highway was extended to Peck Avenue in Fresh Meadows.[26] Further east in Queens, a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) section of the highway in the vicinity of Alley Pond Park, between Cloverdale Boulevard in Bayside and Little Neck Parkway, officially opened on September 25, 1957.[27][28] The highway segment reduced the need for cars to use West Alley Road, a winding road that crossed the park.[27][29]

On September 30, 1958, the first section of the Long Island Expressway outside New York City, a 5-mile (8.0 km) segment from the Queens–Nassau line to Willis Avenue in Albertson, officially opened to traffic.[30] The section of the Long Island Expressway west of the Clearview Expressway was designated as I-495 in October 1958.[2] The Long Island Expressway's extension to Guinea Woods Road in Roslyn was officially opened on September 29, 1959, which allowed eastbound traffic to continue onto the eastbound Northern State Parkway by using a short ramp, and vice versa for westbound traffic. By this time, the Long Island Expressway was continuous between Bayside and Roslyn, although the portion of the Long Island Expressway near the Clearview Expressway (I-295) was not yet completed.[31]

By early 1960, the Long Island Expressway saw more than 120,000 vehicles per day, although congestion frequently built up at Bayside where there was a gap in the Long Island Expressway. The marshy land in the vicinity of Flushing Meadows–Corona Park caused cracking on the expressway's pavement.[32] The 0.9-mile (1.4 km) segment of the Long Island Expressway near the Clearview Expressway, between Peck Avenue and 224th Street, and the interchange's eight overpasses and ramps, officially opened on August 12, 1960.[33]

Segment east of Roslyn

After the opening of the Clearview interchange, the Long Island Expressway was open between Manhattan and Roslyn and entirely designated as NY 24. The old surface alignment of NY 24 south of the expressway became NY 24A.[34] The LIE was extended east from the Northern State Parkway split to NY 106/107 in Jericho by 1960,[34][35] and was then opened to South Oyster Bay Road in Syosset in December 1960.[36] By 1962, the NY 24 designation was removed from the LIE and reassigned to its former surface alignment to the south while the portion of the freeway east of the Clearview Expressway became NY 495 (and later, I-495).[35][37]

Over one-third of I-495 within Suffolk County—a 15-mile (24 km) section from Melville to Veterans Memorial Highway (now NY 454) near Islandia—was opened to traffic between 1962 and 1963.[37][38] A 5-mile extension of I-495 from Oyster Bay Road to NY 110 in Melville opened in August 1962, bringing the highway into Suffolk County.[39] This was followed by a 3.5-mile (5.6 km) extension from NY 110 to Deer Park Road in October of that year,[40] and a further 6.5-mile (10.5 km) extension to NY 454 in August 1963.[41]

Two more sections of I-495—from Islandia to exit 61 in Holbrook and from William Floyd Parkway to exit 71 near Riverhead—were completed in the mid-1960s.[42][43] The section of I-495 between William Floyd Parkway and Riverhead was opened as a discontinuous highway segment in June 1969,[44] and the freeway gap between Holbrook and William Floyd Parkway was filled in December 1969.[45][46] The last 2 miles (3.2 km) of I-495 from exit 71 to CR 58 were opened to traffic on June 28, 1972.[47][48] By the time I-495 had been completed, it was being used by over 150,000 vehicles a day.[48] From the outset, a minimum speed limit of 40 miles per hour (64 km/h) was enforced on the segment of I-495 in Nassau and Suffolk counties.[49]

1960s and 1970s

Traffic volumes on I-495 had grown steadily through the 1960s, growing twenty percent in a three-year period between 1964 and 1967. By the late 1960s, some sections of the highway could no longer handle the amount of traffic that used it each day, and average rush-hour speeds were about 5 miles per hour (8.0 km/h). Major chokepoints existed at the intersections of I-278, the Grand Central Parkway, I-678, I-295, and the Cross Island Parkway. Other bottlenecks existed in Elmhurst, Queens, where a westbound exit to Junction Boulevard was immediately adjacent to a westbound entrance from 108th Street.[49]

In 1966, the New York City Board of Estimate approved the reconstruction of the cloverleaf interchange between I-495 and I-278 in Queens.[50] The intersection would be rebuilt and replaced over three years at a cost of $68 million. At that location, tight ramps and traffic lights would be replaced with a three-level grade-separated interchange, and a new double-decked highway would be built between Maurice Avenue and 48th Street.[49] A ramp from the eastbound I-495 to I-278 opened in 1968.[51]

In 1970, work commenced on a two-year project to install a Jersey barrier in the median of I-495 from 108th Street to Little Neck Parkway. Previously, there was only a 12-foot-wide (3.7 m) reservation separating opposing traffic.[52]

Plans to widen I-495 between I-278 and I-678 were announced by New York City mayor John Lindsay in 1968. The expressway would be expanded from three to five lanes in each direction between these two interchanges.[53] In the 1970s, the federal government gave $270 million for the project.[54] However, by 1978, the New York state government had retracted the interstate designation for that segment. The funds were split three ways for mass transit, highways, and improvements to the Long Island Expressway.[54][55] The LIE was allocated $80 million to improve medians and widen shoulders.[55] By the 1980s, the stretch of the LIE between I-278 and the Grand Central Parkway was frequently carrying 110% of its traffic capacity. In 1981, officials proposed several improvements for that highway segment, including adding a two-lane grade-separated service road between the two highways; realigning service roads at 69th and 108th Streets; and improving entrance and exit ramps.[54]

Lighting

Initially, I-495 lacked proper lighting along its route in Nassau and Suffolk counties for many years. Because of this, during the night, motorists would be driving into complete darkness after crossing the Queens-Nassau border. Despite constant requests from Nassau local officials, no immediate plans were made until 1980, when the first streetlights were installed in eastern Nassau County. The state government planned to add about 1,425 lamps between the Queens-Nassau border and Nicolls Road (exit 62) since that segment of I-495 was heavily used. East of Nicolls Road, vehicle usage dropped sharply, so no lights were planned.[56] The final streetlights were installed between exits 39 and 40 in 2002 in Nassau County.[2]

HOV lanes

In 1988, as part of a proposed $3 billion bond issue, the New York state government proposed adding a fourth lane in each direction to I-495 between Jericho and Medford.[57] After years of discussion, in 1991, the state approved the construction of the fourth lanes to I-495 east of the Cross Island Parkway; the additional lanes would be marked as high-occupancy vehicle lanes (HOV).[58] The lanes were built in subsequent sections. The first section to open, a 12-mile section in western Suffolk County, was opened in May 1994.[59] The lanes soon became well known due to a combination of advertising and free publicity in news articles, and they were heavily patronized even outside of peak hours.[60] The lanes were completed on June 30, 2005, at which point they ran from exit 32 in eastern Queens to exit 64 at Medford in Suffolk County.[2]

Construction of the HOV lanes within Queens was delayed due to opposition from local officials and the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.[61] The HOV segment in Queens was later canceled altogether in 1998, when governor George Pataki announced that the additional lanes between exits 30 and 32 in Queens would be entrance and exit lanes, rather than HOV lanes.[62] In addition, the HOV project would have rebuilt many bridges along I-495 between exits 33 and 40 in Nassau County. As a concession to homeowners, the HOV lanes were narrowed and built within the existing roadbed, and the bridges were largely kept as is.[63]

Interchange improvements

Starting in 1998, I-495 was rebuilt between exit 15 (Van Dam Street) and exit 22 (Grand Central Parkway).[64] The renovation cost $200 million and entailed renovating the highway's main and service roads; improving bridges; and replacing drains.[2] The service roads for exit 19 were rebuilt between 74th Street and Queens Boulevard. There were also plans to rebuild westbound exit 16 to Greenpoint Avenue in Long Island City.[64]

The state announced a plan to renovate I-495 in the vicinity of Alley Pond Park and the Cross Island Parkway in 1995.[65] In 2000, Pataki and New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani announced that this segment of I-495 between exits 29 and 32, near Alley Pond Park and the Cross Island Parkway, would be rebuilt at a cost of $112 million.[66][67][68] The project was announced after the cancellation of the HOV lanes within Queens.[68] Work started in August 2000 and was substantially completed by 2005.[69] The project included the restoration of 12 acres (4.9 ha) within the park, as well as the construction of new ramps to and from the Cross Island Parkway at exit 30.[64] As part of the reconstruction, two cloverleaf ramps were replaced with flyovers; the shoulders in each direction were converted into travel lanes; the westbound exit 31 to Douglaston Parkway was closed; and new collector-distributor ramps were installed east of the Cross Island Parkway interchange.[69][68]

Starting in 2004, the NYSDOT examined proposals to reconfigure exit 22 with I-678 and the Grand Central Parkway in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. These included plans to construct direct ramps between the highways; relocating the service roads of I-495 so the mainline expressway could be widened; and rebuilding the at-grade junction between College Point Boulevard and Horace Harding Expressway.[70] The interchange with Grand Central Parkway was rebuilt from spring 2015 to February 2018, with the replacement of the three overpasses carrying I-495 over the parkway. The $55 million reconstruction included extending merge lanes, replacing and adding lighting, and improving drainage structures.[71][72][73]

Service roads and proposed interchange

As I-495 was being built across Long Island, it was specifically designed to accommodate certain topographical conditions and proposed interchanges. Exit 30 was originally a partial cloverleaf interchange with the Cross Island Parkway, while eastbound exit 30S was for Easthampton Boulevard with a connecting ramp to the southbound Cross Island Parkway. Exit 31 was originally a westbound only interchange for Douglaston Parkway;[74] it was later combined with the exit for the Little Neck Parkway. Exit 39A was intended for the proposed extension of the Wantagh State Parkway near Powell Road in Old Westbury. It was intended to be a full Y interchange with an east-to-southbound-only off-ramp and a north-to-westbound-only on-ramp running beneath Powell Road.[75][76]

Exit 40 originally had only same-directional off-ramps under the expressway providing access to realigned sections of NY 25. When exit 41 was originally constructed, it had no south-to-west connecting ramp. Westbound access to the expressway was provided at the nearby exit 40 on-ramp at NY 25.[77] An alternate design for exit 42 called for it to be similar to the one proposed for NY 135 and Bethpage State Parkway,[78] and westbound exit 46 was originally a partial cloverleaf.[79][80] Exit 47 was intended for the extension of the Bethpage State Parkway near Washington Avenue in Plainview. This was to be a partial cloverleaf with southbound-only off-ramps and northbound-only on-ramps in both directions. The west-to-southbound ramp would also have an additional connecting ramp to a two-way frontage road for a development and an industrial area near exit 46.[81] The site of exit 47 is now a truck inspection site between exits 46 and 48, which opened in 2006.[82]

The original rights-of-way for the service roads between exits 48 and 49 were intended to weave around the steep Manetto Hills area of the main road, rather than running parallel to the road as it does today. The land between the service road and the main road was reserved for housing developments. The right-of-way for the original westbound service road still weaves through the development on the north side of the road.[83] Exit 49 was originally a cloverleaf interchange with the outer ramps connecting to the service roads at a point closer to NY 110. This was in preparation for NY 110's formerly proposed upgrade into the Broad Hollow Expressway. After the project was canceled in the 1970s, the west-to-northbound on-ramp was moved to nearby CR 3 (Pinelawn Road), and the original ramp was replaced with a park and ride.

Exit 52 (Commack Road/CR 4) was intended to be moved west to an interchange with the formerly proposed Babylon–Northport Expressway (realigned NY 231) in the vicinity of the two parking areas. These ramps would have been accessible from the service roads. The westbound off-ramp and service road at exit 54 (Wicks Road/CR 7) originally terminated at Long Island Motor Parkway, east of Wicks Road. The westbound on-ramp was squeezed between the northwest corner of the Wicks Road bridge and exit 53. Excessive weaving between exits 52, 53, and 54 caused NYSDOT to reconstruct all three interchanges into one, and replace the west-to-southbound off-ramp to Sagtikos State Parkway with a flyover ramp.[84] Exit 55A was meant to be a trumpet interchange for the Hauppauge Spur of NY 347, between Long Island Motor Parkway (exit 55) and NY 111 (exit 56). The service roads were intended to go around the interchange, rather than run parallel to the main road. Ramps on the east side of Motor Parkway and west side of NY 111 would be eliminated as part of the interchange's construction. Between exits 57 and 58, there was a proposed extension of Northern State Parkway.[85]

Prior to the construction of the interchange with CR 97 (Nicolls Road), exit 62 was for Morris Avenue and Waverly Avenue eastbound, and Morris Avenue westbound.[86][87] Between exits 63 and 64, the eastbound service road was intended to weave around a recharge basin and replace a local residential street. Residents would have lived on both sides of the service road, similar to the segment between exits 59 and 60.[88] Exit 68 was originally planned to be built as a cloverleaf interchange without collective-distributor roads.[89] Additionally in the 1970s, Suffolk County Department of Public Works proposed an extension of East Main Street in Yaphank (CR 102) that would have terminated at the west end of this interchange.[90]

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Suffolk County Planning Department considered extending CR 55 to the Grumman Calverton Naval Air Base between exits 70 and 71. This would have provided an additional interchange known as exit 70A. Exit 71 itself was intended to be a cloverleaf interchange with CR 94 (Nugent Drive) and the Hamptons Spur of the Long Island Expressway.[91] After the Hamptons Spur proposal was cancelled, the plans for exit 71 were altered to call for a complete diamond interchange.

Unbuilt expansions

Extensions of the expressway

Across Manhattan

Plans for I-495 called for it to extend across Manhattan on the Mid-Manhattan Expressway to the Lincoln Tunnel, which it would follow into New Jersey and connect to I-95 in Secaucus. The I-495 designation was assigned to the New Jersey approach to the tunnel in anticipation of the Mid-Manhattan Expressway being completed.[42] However, the project was cancelled and the Mid-Manhattan Expressway was officially removed from I-495 on January 1, 1970.[92] The New Jersey stretch of I-495 became New Jersey Route 495 in 1979.[93]

Manhattan Borough President Samuel Levy first proposed the Mid-Manhattan Expressway connector in 1936.[94] The plan called for an expressway link crossing midtown Manhattan near 34th Street, then, as now, a heavily traveled crosstown surface street. The original idea was a pair of two-laned tunnels, the Mid-Manhattan Expressway or M.M.E. (sometimes called the Mid-Manhattan Elevated Expressway) connecting the West Side Highway on Hudson River and the Franklin D. Roosevelt East River Drive on the East River. By 1949, Robert Moses, New York City Parks Commissioner and Arterial Coordinator, proposed a six-lane elevated expressway along 30th Street. The expressway was to have two exits, to connect to the West Side Highway and the Lincoln Tunnel on the west side of Manhattan, and also to the Queens–Midtown Tunnel and FDR Drive on the east side of the island.[95] It would be constructed within a 100-foot (30 m)-wide right-of-way immediately south of 30th Street. The viaduct would require substantial demolition of high-rise buildings within Midtown Manhattan. To cover the costs of construction, Moses suggested charging tolls on the new roadway, which was estimated to cost $26 million to construct plus another $23 million for the land needed for the project.[96]

A later proposal had the roadway situated ten stories above valuable commercial real estate. Air rights above the expressway would be sold and new high-rise buildings would be constructed above the expressway; buildings would be constructed below the viaduct as well. One unusual variation involved running the roadway through the sixth and seventh floors of the Empire State Building.[97][98] In 1963, plans for the expressway were finalized, and it received the I-495 designation. Beginning from its elevated connections to 12th Avenue (NY 9A) or the West Side Elevated Highway, the Mid-Manhattan Expressway would mostly follow 30th Street east of Ninth Avenue. The expressway would travel east as a six-lane elevated route, ten stories above the city streets to allow for commercial development both above and below the skyway deck. At Second Avenue, it would swing north for connections with the FDR Drive. Between First and Second Avenues, ramps would be constructed to provide access to the Queens–Midtown Tunnel.[99][100]

In December 1965, Moses canceled his plans for the Mid-Manhattan Expressway due to opposition from the city government, which wanted to build a crosstown tunnel instead.[101] The Mid-Manhattan Expressway project was ultimately canceled and the I-495 designation removed from the expressway on January 1, 1970.[102] In 1971, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller removed state plans for the Mid-Manhattan Expressway, along with about a dozen other highway plans including I-78 through New York City, of which another crosstown highway known as the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX) was part.[103]

Across Suffolk County

Long Island, meanwhile, lobbied to extend I-495 east over NY 495. The extension took place in the early 1980s, at which time the NY 495 signs were taken down and I-495 was extended to the east end of the LIE. The section of I-495 in the vicinity of the Lincoln Tunnel was redesignated as NY 495 at this time. The extension of I-495 to Riverhead makes the highway a spur, which should have an odd first digit according to the Interstate Highway System's numbering scheme. Even first digits are usually assigned to bypasses, connectors, and beltways, as I-495 was prior to the 1980s.[2] A proposed Long Island Crossing would have extended the LIE across Long Island Sound to I-95 in either Guilford, Connecticut, Old Saybrook, Connecticut, or Rhode Island via a series of existing and man-made islands, but a lack of funding as well as public opposition led to the demise of these proposals.[104]

CR 48 in Suffolk County was originally intended to become part of the North Fork extension of the Long Island Expressway.[83][105]

Subway line

A New York City Subway line along the Long Island Expressway corridor had been proposed in the 1929 and 1939 IND Second System plans as an extension of the BMT Broadway Line east of the 60th Street Tunnel, prior to the construction of the expressway.[106][107][108] These were the predecessors to a line proposed in 1968 as part of the Program for Action. It would have split from the IND Queens Boulevard Line west of the Woodhaven Boulevard station and go to Kissena Boulevard via a right-of-way parallel and adjacent to the LIE.[109] In Phase I, it would go to Kissena Boulevard at Queens College, and in Phase II, to Fresh Meadows and Bayside.[106] This "Northeastern Queens" line would have been built in conjunction with the planned widening of the expressway. The subway tracks would have been placed under the expressway or its service roads, or in the median of a widened LIE in a similar manner to the Blue Line of the Chicago "L".[109][106][110][111][112] It had been previously proposed to run the line from the 63rd Street tunnel under Northern Boulevard to Flushing (near the current Main Street station), then south under Kissena and Parsons Boulevards to meet with the LIE at Queens College.[112]

The LIE line was approved in July 1968.[113] The line was opposed by many residents of the surrounding communities because it would entail widening I-495, which would necessitate the demolition of nearby homes.[114] By 1973, the final design for the Northeast Queens LIE line was published.[106] However, later that year, the LIE line was canceled because New York state voters had declined a $3.5 billion bond measure that would have paid for five subway extensions, including the LIE line. This was the second time that voters declined a bond issue to finance this extension, with the first being on November 2, 1971, for $2.5 billion.[115]

Exit list

| County | Location | mi[1][116] | km | Exit | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manhattan | Murray Hill | 0.00 | 0.00 | 34th Street / 35th Street / Second Avenue / 37th Street / Third Avenue / 38th Street / 41st Street – Downtown, Crosstown, Uptown | Westbound exits from the Queens–Midtown Tunnel | |

| Second Avenue / 34th Street / 40th Street | Eastbound entrances to the Queens–Midtown Tunnel | |||||

| East River | 1.01 | 1.63 | Queens–Midtown Tunnel (toll) | |||

| Queens | Hunters Point | 1.43 | 2.30 | 13 | Borden Avenue – Pulaski Bridge | Eastbound exit and entrance |

| 1.53 | 2.46 | 14 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance; western terminus of NY 25A | |||

| Long Island City | 2.09 | 3.36 | 15 | Van Dam Street – Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge | Westbound exit and entrance | |

| 2.34 | 3.77 | 16 | Hunters Point Avenue / Greenpoint Avenue – Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | ||

| 2.61 | 4.20 | 17W | Exits 35A-B on I-278; access via service roads | |||

| 17E | Westbound exit is via exit 17W and 48th Street | |||||

| Maspeth | 3.47 | 5.58 | 18 | Maurice Avenue | Eastbound exit is part of exit 17 | |

| Elmhurst | 4.30 | 6.92 | – | 69th Street / Grand Avenue | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance; part of exit 19 | |

| 5.27 | 8.48 | 19 | No eastbound entrance from Woodhaven Boulevard | |||

| 5.58 | 8.98 | 20 | Junction Boulevard | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | ||

| Corona | 6.91 | 11.12 | 21 | 108th Street | Westbound exit is part of exit 22A | |

| 7.25 | 11.67 | 22A | Signed eastbound as exits 22A (east) and 22B (west); exits 10E-W on Grand Central Parkway | |||

| 7.35 | 11.83 | 22B | Signed eastbound as exits 22C (I-678 south), 22D (I-678 north), 22E (C.P. Blvd); exits 12A-B on I-678 | |||

| Flushing | 8.45 | 13.60 | 23 | Main Street | ||

| 9.10 | 14.65 | 24 | Kissena Boulevard | Eastbound access to 164th Street | ||

| Fresh Meadows | 10.02 | 16.13 | 25 | Utopia Parkway / 164th Street / 188th Street – St. John's University | Signed for 188th Street eastbound and 164th Street westbound | |

| 11.04 | 17.77 | 26 | Francis Lewis Boulevard | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| Bayside | 11.43 | 18.39 | 27 | Signed as exits 27S (south) and 27N (north); exits 4E-W on I-295 | ||

| 11.93 | 19.20 | 28 | Oceania Street / Francis Lewis Boulevard | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance; also serves 188th Street | ||

| 12.31 | 19.81 | 29 | Springfield Boulevard | |||

| 12.91 | 20.78 | 30 | East Hampton Boulevard / Douglaston Parkway | Eastbound exit only | ||

| Oakland Gardens | 13.27 | 21.36 | 31S | Exits 30E-W on Cross Island Parkway | ||

| 31N | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |||||

| Little Neck | 14.25 | 22.93 | 32 | Little Neck Parkway / Douglaston Parkway | No eastbound signage for Douglaston Parkway | |

| Nassau | Lake Success | 15.43 | 24.83 | 33 | Lakeville Road (CR 11) / Community Drive (CR 11A) – Great Neck | |

| – | HOV 2+ Lane east | Western terminus of HOV lane | ||||

| North Hills | 16.37 | 26.34 | 34 | New Hyde Park Road (CR 5B) | ||

| 17.57 | 28.28 | 35 | Shelter Rock Road (CR 8) – Manhasset | Westbound exit is via exit 36 | ||

| 18.43 | 29.66 | 36 | Searingtown Road (CR 101) – Port Washington | |||

| Roslyn Heights | 18.95 | 30.50 | 37 | Willis Avenue – Mineola, Roslyn | ||

| East Hills | 20.14 | 32.41 | 38 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance; exit 29A on Northern Parkway | ||

| Old Westbury | 20.31 | 32.69 | 39 | Glen Cove Road (CR 1) – Hempstead, Glen Cove | ||

| Jericho | 24.07 | 38.74 | 40 | Signed as exits 40W (west) and 40E (east) | ||

| 25.23 | 40.60 | 41 | Signed as exits 41S (south) and 41N (north) | |||

| 26.05 | 41.92 | 42 | Same-directional exit ramps only; entrance ramps located west of exit 46 | |||

| Syosset | 43A | Robbins Lane | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |||

| 27.07 | 43.56 | 43 | South Oyster Bay Road (CR 9) – Bethpage, Syosset | |||

| 27.83 | 44.79 | 44 | Signed as exits 44S (south) and 44N (north) eastbound; exits 13E-W on NY 135 | |||

| Plainview | 28.17 | 45.34 | 45 | Manetto Hill Road – Plainview, Woodbury | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |

| 28.95 | 46.59 | 46 | Sunnyside Boulevard – Plainview | |||

| 29.65 | 47.72 | Truck inspection station (eastbound) | ||||

| Nassau–Suffolk county line | Plainview–Melville hamlet line | 29.68 | 47.77 | 48 | Round Swamp Road (CR 110) – Old Bethpage, Farmingdale | |

| Suffolk | Melville | 31.82 | 51.21 | 49 | Signed as exits 49S (south) and 49N (north) | |

| Dix Hills | 34.25 | 55.12 | 50 | Bagatelle Road – Dix Hills, Wyandanch | ||

| 35.87 | 57.73 | 51 | ||||

| 37.00 | 59.55 | Rest Area & Long Island Welcome Center (eastbound) | ||||

| Dix Hills | 38.56 | 62.06 | 52 | Westbound exit is part of exit 53 | ||

| Brentwood | 39.28 | 63.22 | 53 | Exits S1E-W on Sagtikos Parkway | ||

| 54 | Now an unnumbered interchange via exit 53 | |||||

| 41.72 | 67.14 | 55 | ||||

| Hauppauge | 42.66 | 68.65 | 56 | |||

| Islandia | 44.30 | 71.29 | 57 | |||

| 45.64 | 73.45 | 58 | Old Nichols Road – Central Islip, Nesconset | |||

| Ronkonkoma | 47.50 | 76.44 | 59 | |||

| 48.19 | 77.55 | 60 | ||||

| Holbrook | 49.62 | 79.86 | 61 | |||

| Holtsville | 51.24 | 82.46 | 62 | |||

| Farmingville | 53.04 | 85.36 | 63 | |||

| Medford | 54.29 | 87.37 | 64 | |||

| – | HOV 2+ Lane west | Eastern terminus of HOV lane | ||||

| 55.44 | 89.22 | 65 | ||||

| Yaphank | 57.41 | 92.39 | 66 | |||

| 58.55 | 94.23 | 67 | ||||

| 60.17 | 96.83 | 68 | Signed as exits 68S (south) and 68N (north) westbound | |||

| Manorville | 64.05 | 103.08 | 69 | Wading River Road (CR 25) – Wading River, Center Moriches | ||

| 65.25 | 105.01 | 70 | Northern terminus of CR 111; no westbound signage for NY 27 | |||

| Calverton | 69.27 | 111.48 | 71 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance; northbound terminus of NY 24 | ||

| 70.75 | 113.86 | 72 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |||

| 71.02 | 114.30 | 73 | ||||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| ||||||

Mid-Manhattan Expressway (canceled)

If built, the Mid-Manhattan Expressway would have the following exits:[95]

| mi | km | Destinations | Notes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 0.00 | Continuation into New Jersey | ||||||

| 0.20 | 0.32 | |||||||

| 1.50 | 2.41 | |||||||

| 1.65 | 2.66 | Continuation into Queens | ||||||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| ||||||||

See also

- 495 Productions - Reality show production company named for the highway

- L.I.E. - 2001 film whose title is based on the initials of the highway

References

- "2008 Traffic Volume Report for New York State" (PDF). New York State Department of Transportation. June 16, 2009. pp. 239–241. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- Anderson, Steve. "Long Island Expressway". NYCRoads. Archived from the original on April 2, 2010. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- New York State Department of Transportation (January 2017). Official Description of Highway Touring Routes, Bicycling Touring Routes, Scenic Byways, & Commemorative/Memorial Designations in New York State (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- Google (April 21, 2018). "I-495, New York" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- Popik, Barry. "Entry from June 29, 2011 World's Longest Parking Lot (Long Island Expressway". Archived from the original on September 29, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- "Long Island Expressway". Historical Sign Listings. New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. November 27, 2001. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- "Plans Are Changed For Queens Subway: Traffic Crossings At Nassau And Woodhaven Boulevards Altered To Avoid Congestion. Viaduct Project Dropped; Main Driveway To Be Depressed, Side Routes To Be At Grade-- New Bids Due Soon". The New York Times. June 22, 1930. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- "Highway Program Aids Long Island Growth". The New York Times. April 27, 1930. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- Walsh, Kevin (November 2013). "NYC STREETS FEATURING FULL NAMES". Forgotten NY. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- "HOV Lane Information". MetroPool Long Island. Archived from the original on October 25, 2010. Retrieved November 6, 2010.

- "$58,000,000 Tunnel to Queens Opened". The New York Times. November 16, 1940. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- New York (Map). Cartography by General Drafting. Esso. 1940.

- New York with Pictorial Guide (Map). Cartography by General Drafting. Esso. 1942.

- Official Highway Map of New York State (Map) (1947–48 ed.). Cartography by General Drafting. State of New York Department of Public Works.

- "Queens Trolley in the 1930s: Future Sites of the Long Island Expressway" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s449jDBcyWM

- "Road Plan Allots 60 Million To City; Agreement Reached On Terms Of Legislation At Albany By Moses And Board". The New York Times. February 20, 1945. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- "Queens Expressway Link Open". The New York Times. June 26, 1955. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- New York (Map). Cartography by Rand McNally and Company. Sunoco. 1952.

- New York with Special Maps of Putnam–Rockland–Westchester Counties and Finger Lakes Region (Map) (1955–56 ed.). Cartography by General Drafting. Esso. 1954.

- "3 Road Links to Open: Parts of Big Highway System to Go Into Use Nov. 5". The New York Times. October 13, 1955. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- "New York with Special Maps of Putnam–Rockland–Westchester Counties and Finger Lakes Region" (Map). Esso. Cartography by General Drafting. 1956.

- "Plan Board Adopts Express Way Route: 8-Mile Section Across Queens to Nassau County Line to Be Financed by State". The New York Times. May 24, 1951. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- "Nassau Road Route Set: Horace Harding Expressway Link to Cut Through Deepdale Club". The New York Times. July 26, 1952. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- "Dewey Speeds L. I. Expressway: Approves Bill to Add 64 Miles: Governor Speeds L. I. Expressway". The New York Times. March 28, 1954. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- Stengren, Bernard (June 10, 1958). "Road Crews Work on 3 'Knots' Here: Queens and Brooklyn Snarls to Be Unraveled by '60, Some Experts Predict". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- Godbout, Oscar (August 15, 1959). "Perilous Detour in Queens to End: Work on L. I. Expressway to Eliminate Barrier That Caused 31 Accidents". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- "L. I. Expressway Opens Queens Link Tomorrow". The New York Times. September 24, 1957. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- "$8.75-million Expwy Link to Open". Daily News (New York, New York). September 24, 1957. p. B7.

- "Expwy Link Slighted — Wait Till Weekend". Daily News (New York, New York). September 26, 1957. p. XQ3.

- "News from the Field of Travel". The New York Times. September 28, 1958. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- "L. I. Expressway to Open 2 Links: Stretch at Roslyn and New Northern State Access to Go Into Use Tuesday". The New York Times. September 26, 1959. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- Stengren, Bernard (February 7, 1960). "L.I. EXPRESSWAY 2D BUSIEST HERE; 120,616 Vehicles Use Artery Daily -- Bottlenecks Are Problems in Bayside". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- "18-Month Bottleneck Is Ended On L.L. Expressway at Clearview". The New York Times. August 13, 1960. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- New York and New Jersey Tourgide Map (Map). Cartography by Rand McNally and Company. Gulf Oil Company. 1960.

- New York and Metropolitan New York (Map) (1961–62 ed.). Cartography by H.M. Gousha Company. Sunoco. 1961.

- "L.I. Expressway Link Opened". The New York Times. December 16, 1960. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- New York with Sight-Seeing Guide (Map) (1962 ed.). Cartography by General Drafting. Esso. 1962.

- New York Happy Motoring Guide (Map) (1963 ed.). Cartography by General Drafting. Esso. 1963.

- "EXPRESSWAY LINK IS OPENED ON L.I.; New 5-Mile Section Extends Highway to Route 110 in Suffolk County". The New York Times. August 16, 1962. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- "EXPRESSWAY ADDS 3 %-MILE SECTION; Huntington Link Completes Half of Long Island Road". The New York Times. October 4, 1962. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- "2 ROAD SECTIONS ARE READY ON L.I.; Expressway and Wantagh Extensions to Open". The New York Times. August 21, 1963. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- New York (Map). Cartography by Rand McNally and Company. Mobil. 1965.

- New York (Map) (1969–70 ed.). Cartography by General Drafting. Esso. 1968.

- "L.I. Expressway Section to Open". The New York Times. June 10, 1969. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "Expressway Route to Open". The New York Times. December 17, 1969. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- New York Thruway (Map). Cartography by Rand McNally and Company. New York State Thruway Authority. 1971.

- Eichel, Larry (June 29, 1972). "It's the End of the Road for the LIE". Newsday. New York City.

- Andelman, David A. (June 24, 1972). "L. I. Expressway Nears End of 32‐Year Construction". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- Ingraham, Joseph C. (August 21, 1967). "L.I. Expressway to Be Snarled for Years; Improvements Begun but Many Obstacles Slow the Work L.I. Expressway to Be Snarled for Many Years". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- Bennett, Charles G. (May 21, 1966). "$32-Million Queens Cloverleaf Approved by Board of Estimate; It Will Link Brooklyn-Queens and Long Island Expressways 50 Maspeth Homeowners Protest Vainly". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "Queens Changes in Effect On L.I. Expressway Today". The New York Times. September 16, 1968. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "L.I. Xway Divider Job Will Take Two Years". Daily News. New York. July 14, 1970. p. 280. Retrieved January 13, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ingraham, Joseph C. (January 27, 1968). "City to Widen a 5-Mile Stretch Of L. I. Expressway in Queens; Plans Call for 4 New Lanes Along the Busiest Section --Work to Start in 1970 CITY WILL WIDEN L. I. EXPRESS WAY". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- Dallas, Gus (October 4, 1981). "Paving way for decongesting LIE". Daily News. New York. p. 491. Retrieved January 2, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Dembart, Lee (December 23, 1978). "City to Ask Trade‐In of Aid Set for L.I. Expressway". The New York Times. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- McQuiston, John T. (April 12, 1981). "LIGHTS GO UP ON THE EXPRESSWAY". The New York Times. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- "Pact to Widen L.I. Expressway Is Announced". The New York Times. September 29, 1988. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- Lyall, Sarah (January 3, 1991). "Long Island Expressway to Get a Fourth Lane, for Ride Sharers". The New York Times. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- "For Traffic-Jammed Drivers on Long Island, 12 Miles of Relief". The New York Times. May 26, 1994. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- Lutz, Phillip (October 30, 1994). "H.O.V. Lane Fulfills Goals In Peak Time". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- Lii, Jane H. (July 14, 1996). "NEIGBORHOOD REPORT: DOUGLASTON;2 Suits Slow Plans for a Speedier Long Island Expressway". The New York Times. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- Rohde, David (May 14, 1998). "Pataki Cancels Plan to Widen Expressway in Part of Queens". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- Rather, John (August 22, 1993). "Officials Garner Concessions on L.I.E. Widening in Nassau". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- Louis, Kathleen (August 23, 2001). "LIE Construction In Queens Will Last At Least Two More Years". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- Lii, Jane H. (December 10, 1995). "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: DOUGLASTON;More L.I.E., Fewer Trees?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- Harney, James (February 16, 2000). "Major LIE upgrading agreed on". New York Daily News. p. 200. Retrieved April 12, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

. - "Press Release Archives - GOVERNOR PATAKI AND MAYOR GIULIANI ANNOUNCE LONG ISLAND EXPRESSWAY PLAN TO IMPROVE ALLEY POND PARK AND MOTORIST SAFETY". Welcome to NYC.gov. February 7, 2000. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- "LIE, Cross Island lanes to close for construction". TimesLedger. June 20, 2002. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- "NYSDOT-LIE/CIP, Queens Reconstruction Project". New York State Department of Transportation. December 1, 2004. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- Brodsky, Robert (May 13, 2004). "State Eyes Traffic Changes At L.I.E./GCP/Van Wyck Interchange". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- "Extensive construction work on the LIE in Flushing is complete". TimesLedger. February 8, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- Mascali, Nikki M. (February 7, 2018). "Bridge reconstruction on LIE/GCP reaches final phase: Cuomo". Metro US. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- "Governor Cuomo Announces Completion of the $58 Million Reconstruction of Three Bridges at the Long Island Expressway/Grand Central Parkway Interchange in Queens". Governor Andrew M. Cuomo. February 6, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- Saltzman, Jeff. "LIE/Cross Island Interchange Reconstruction 2001". Archived from the original on May 16, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- Anderson, Steve. "Wantagh State Parkway". NYCRoads. Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- "Long Island Expressway near proposed Wantagh Parkway Extension (WikiMapia)". Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- "Long Island Expressway & Jericho Turnpike Interchange (WikiMapia)". Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- Map of Nassau County, Long Island, New York (Map). Hagstrom Map. 1940. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- "Long Island Expressway and Sunnyside Boulevard (Original exit 46)". Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- NY 135/LIE Interchange project – Recommended Modified Alternative (Map). New York State Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on February 28, 1997. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- "Long Island Expressway at the vicinity of formerly proposed Bethpage State Parkway Interchange (WikiMapia)". Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- Domash, Shelly Feuer (April 9, 2006). "Checking Trucks, for Safety's Sake". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Atlas of Suffolk County, New York (Map). Hagstrom Map. 1969.

- Vincent, Stuart (March 30, 1988). "Unsnarling a Dangerous Interchange; Remedies eyed for Commack troublespot". Newsday. New York City.

- Map of proposed interchange (Map). Suffolk County Department of Public Works. 1963. Archived from the original on November 29, 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- Aerial Photo by Lockwood, Kessler & Bartlett, Incorporated Consulting Engineers of Syosset, New York (Pre-1971 Nicolls Road)

- Street Map of Lake Ronkonkoma, Holbrook, Farmingville, and Vicinity (Map). Mooney, Frank J. 1971–72.

- [1975 NYSDOT Map (but other evidence exists)]

- Proposed Park and Ride Center at Yaphank (Map). Suffolk County Department of Planning.

- "County Road System – County of Suffolk, New York" (PDF). Suffolk County Department of Public Works. December 29, 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 20, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- Proposed Park and Ride Center at Calverton (Map). Suffolk County Department of Planning.

- State of New York Department of Transportation (January 1, 1970). Official Description of Touring Routes in New York State (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- "Route 495 Straight Line Diagram" (PDF). Internet Archives WayBack Machine. New Jersey Department of Transportation. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 21, 2006. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- "CROSSTOWN TUNNEL DEMANDED BY LEVY; $28,000,000 Bore Through Bed Rock Would Link New Traffic Tubes to Queens and Jersey". The New York Times. September 24, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 27, 2018. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- Anderson, Steve. "Mid-Manhattan Expressway (I-495, unbuilt)". NYCRoads. Archived from the original on April 1, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- Ingraham, Joseph C. (December 30, 1949). "Mid-City Toll Road Backed By Moses". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 27, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- Radlauer, Steve. Non-Driving New Yorker. New York Magazine. New York Media, LLC. p. 76. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- Mansfield, H. (2004). The Bones of the Earth. Shoemaker Hoard. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-59376-040-3. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- "Future Arterial Program for New York City", Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (1963).

- "Moses Urges 3d Queens Tunnel, With Condition; Asserts It Would Be Useless Without City Approval of 2 Expressway Links". The New York Times. June 10, 1963. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Ingraham, Joseph C. (December 29, 1965). "3d Midtown Tube to Start Soon, Moses Says, Shelving Road Plan; Midtown Tube to Start Soon, Moses' Says, Shelving Road Plan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- State of New York Department of Transportation (January 1, 1970). Official Description of Touring Routes in New York State (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- Vines, Francis X. (March 25, 1971). "Lower Manhattan Road Killed Under State Plan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- Anderson, Steve. "Eastern Long Island Sound Crossings". NYCRoads. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- Atlas of Suffolk County, New York (Map). Hagstrom Map. 1973.

- Raskin, Joseph B. (2013). The Routes Not Taken: A Trip Through New York City's Unbuilt Subway System. New York, New York: Fordham University Press. doi:10.5422/fordham/9780823253692.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-82325-369-2.

- Project for Expanded Rapid Transit Facilities, New York City Transit System, dated July 5, 1939

- Duffus, R.L. (September 22, 1929). "Our Great Subway Network Spreads Wider; New Plans Of Board Of Transportation Involve The Building Of More Than One Hundred Miles Of Additional Rapid Transit Routes For New York". The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- "Regional Transportation Program". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- Burks, Edward C. (February 21, 1971). "New Line May Get Double Trackage: Transit Unit Shift on Queens Super-Express". The New York Times. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

- Program for Action maps Archived June 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine from thejoekorner.com

- Kihss, Peter (April 13, 1967). "Study is Started for New Subways: 3 Routes Proposed to Aid Growing Queens Areas". The New York Times. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- "Number One Transportation Progress An Interim Report". thejoekorner.com. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. December 1968. Archived from the original on August 29, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- Schumach, Murray (November 1, 1971). "To Elmhurst Residents, the Issue Is Homes Versus Highways". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- 1968–1973, the Ten-year Program at the Halfway Mark. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 1973.

-

- "New York County Inventory Listing" (CSV). New York State Department of Transportation. August 7, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "Queens County Inventory Listing" (CSV). New York State Department of Transportation. August 7, 2015. Archived from the original on June 28, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "Nassau County Inventory Listing" (CSV). New York State Department of Transportation. August 7, 2015. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "Suffolk County Inventory Listing" (CSV). New York State Department of Transportation. August 7, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

.svg.png.webp)