Intraspecific competition

Intraspecific competition is an interaction in population ecology, whereby members of the same species compete for limited resources. This leads to a reduction in fitness for both individuals, but the more fit individual survives and is able to reproduce.[1] By contrast, interspecific competition occurs when members of different species compete for a shared resource. Members of the same species have rather similar requirements for resources, whereas different species have a smaller contested resource overlap, resulting in intraspecific competition generally being a stronger force than interspecific competition.[2]

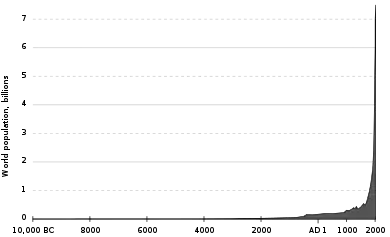

Individuals can compete for food, water, space, light, mates or any other resource which is required for survival or reproduction. The resource must be limited for competition to occur; if every member of the species can obtain a sufficient amount of every resource then individuals do not compete and the population grows exponentially.[1] Prolonged exponential growth is rare in nature because resources are finite and so not every individual in a population can survive, leading to intraspecific competition for the scarce resources.

When resources are limited, an increase in population size reduces the quantity of resources available for each individual, reducing the per capita fitness in the population. As a result, the growth rate of a population slows as intraspecific competition becomes more intense, making it a negatively density dependent process. The falling population growth rate as population increases can be modelled effectively with the logistic growth model.[3] The rate of change of population density eventually falls to zero, the point ecologists have termed the carrying capacity (K). However, a population can only grow to a very limited number within an environment.[3] The carrying capacity, defined by the variable k, of an environment is the maximum number of individuals or species an environment can sustain and support over a longer period of time.[3] The resources within an environment are limited, and are not endless.[3] An environment can only support a certain number of individuals before its resources completely diminish.[3] Numbers larger than this will suffer a negative population growth until eventually reaching the carrying capacity, whereas populations smaller than the carrying capacity will grow until they reach it.[3]

Intraspecific competition does not just involve direct interactions between members of the same species (such as male deer locking horns when competing for mates) but can also include indirect interactions where an individual depletes a shared resource (such as a grizzly bear catching a salmon that can then no longer be eaten by bears at different points along a river).

The way in which resources are partitioned by organisms also varies and can be split into scramble and contest competition. Scramble competition involves a relatively even distribution of resources among a population as all individuals exploit a common resource pool. In contrast, contest competition is the uneven distribution of resources and occurs when hierarchies in a population influence the amount of resource each individual receives. Organisms in the most prized territories or at the top of the hierarchies obtain a sufficient quantity of the resources, whereas individuals without a territory don’t obtain any of the resource.[1]

Mechanisms

Direct

Interference competition is the process by which individuals directly compete with one another in pursuit of a resource. It can involve fighting, stealing or ritualised combat. Direct intraspecific competition also includes animals claiming a territory which then excludes other animals from entering the area. There may not be an actual conflict between the two competitors, but the animal excluded from the territory suffers a fitness loss due to a reduced foraging area and is unable to enter the area as it risks confrontation from a more dominant member of the population. As organisms are encountering each other during interference competition, they are able to evolve behavioural strategies and morphologies to out-compete rivals in their population.[4]

.jpg.webp)

For example, different populations of the northern slimy salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) have evolved varying levels of aggression depending on the intensity of intraspecific competition. In populations where the resources are scarcer, more aggressive behaviours are likely to evolve. It is a more effective strategy to fight rivals within the species harder instead of searching for other options due to the lack of available food.[5] More aggressive salamanders are more likely obtain the resources they require to reproduce whereas timid salamanders may starve before reproducing, so aggression can spread through the population.

In addition, a study on Chilean flamingos (Phoenicopterus chilensis) found that birds in a bond were much more aggressive than single birds. The paired birds were significantly more likely to start an agonistic encounter in defense of their mate or young whereas single birds were typically non-breeding and less likely to fight.[6] Not all flamingos can mate in the population because of an unsuitable sex ratio or some dominant flamingos mating with multiple partners. Mates are a fiercely contested resource in many species as the production of offspring is essential for an individual to propagate its genes.

Indirect

Organisms can compete indirectly, either via exploitative or apparent competition. Exploitative competition involves individuals depleting a shared resource and both suffering a loss in fitness as a result. The organisms may not actually come into contact and only interact via the shared resource indirectly.

For instance, exploitative competition has been shown experimentally between juvenile wolf spiders (Schizocosa ocreata). Both increasing the density of young spiders and reducing the available food supply lowered the growth of individual spiders. Food is clearly a limiting resource for the wolf spiders but there was no direct competition between juveniles for food, just a reduction in fitness due to the increased population density.[7] The negative density dependence in young wolf spiders is evident: as the population density increases further, growth rates continues to fall and could potentially reach zero (as predicted by the logistic growth model). This is also seen in Viviparous lizard, or Lacerta vivipara, where the existence of color morphs within a population depends on the density and intraspecific competition.

In stationary organisms, such as plants, exploitative competition plays a much larger role than interference competition because individuals are rooted to a specific area and utilise resources in their immediate surroundings. Saplings will compete for light, most of which will be blocked and utilised by taller trees.[8] The saplings can be easily out-competed by larger members of their own species, which is one of the reasons why seed dispersal distances can be so large. Seeds that germinate in close proximity to the parents are very likely to be out-competed and die.

Apparent competition occurs in populations that are predated upon. An increase in population of the prey species will bring more predators to the area, which increases the risk of an individual being eaten and hence lowers its survivorship. Like exploitative competition, the individuals aren’t interacting directly but rather suffer a reduction in fitness as a consequence of the increasing population size. Apparent competition is generally associated with inter rather than intraspecific competition, whereby two different species share a common predator. An adaptation that makes one species less likely to be eaten results in a reduction in fitness for the other prey species because the predator species hunts more intensely as food has become more difficult to obtain. For example, native skinks (Oligosoma) in New Zealand suffered a large decline in population after the introduction of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus).[9] Both species are eaten by ferrets (Mustela furo) so the introduction of rabbits resulted in immigration of ferrets to the area, which then depleted skink numbers.

Resource partitioning

Contest

Contest competition takes place when a resource is associated with a territory or hierarchical structure within the population. For instance: white-faced capuchin monkeys (Cebus capucinus) have different energy intakes based on their ranking within the group.[10] Both males and females compete for territories with the best access to food and the most successful monkeys are able to obtain a disproportionately large quantity of food and therefore have a higher fitness in comparison to the subordinate members of the group. In the case of Ctenophorus pictus lizards, males compete for territory. Among the polymorphic variants, red lizards have are more aggressive in defending their territory compared to their yellow counterparts.[11]

Aggressive encounters are potentially costly for individuals as they can get injured and be less able to reproduce. As a result, many species have evolved forms of ritualised combat to determine who wins access to a resource without having to undertake a dangerous fight. Male adders (Vipera berus) undertake complex ritualised confrontations when courting females. Generally, the larger male will win and fights rarely escalate to injury to either combatant.[12]

However, sometimes the resource may be so prized that potentially fatal confrontations can occur to acquire them. Male elephant seals, Mirounga augustirostris, engage in fierce competitive displays in an attempt to control a large harem of females with which to mate. The distribution of females and subsequent reproductive success is very uneven between males. The reproductive success of most males is zero; they die before breeding age or are prevented from mating by higher ranked males. In addition, just a few dominant males account for the majority of copulations.[13] The potential reproductive success for males is so great that many are killed before breeding age as they attempt to move up the hierarchy in their population.

Contest competition produces relatively stable population dynamics. The uneven distribution of resources results in some individuals dying off but helps to ensure that the members of the population that hold a territory can reproduce. As the number of territories in an area stays the same over time, the breeding population remains constant which produces a similar number of new individuals every breeding season.

Scramble

Scramble competition involves a more equal distribution of resources than contest competition and occurs when there is a common resource pool that an individual cannot be excluded from. For instance, grazing animals compete more strongly for grass as their population grows and food becomes a limiting resource. Each herbivore receives less food as more individuals compete for the same quantity of food.[4]

Scramble completion can lead to unstable population dynamics, the equal division of resources can result in very few of the organisms obtaining enough to survive and reproduce and this can cause population crashes. This phenomenon is called overcompensation. For instance, the caterpillars of cinnabar moths feed via scramble competition, and when there are too many caterpillars competing very few are able to pupate and there is a large population crash.[14] Subsequently, very few cinnabar moths are competing intraspecifically in the next generation so the population grows rapidly before crashing again.

Consequences of intraspecific competition

Slowed growth rates

The major impact of intraspecific competition is reduced population growth rates as population density increases. When resources are infinite, intraspecific competition does not occur and populations can grow exponentially. Exponential population growth is exceedingly rare, but has been documented, most notably in humans since 1900. Elephant (Loxodonta africana) populations in Kruger National Park (South Africa) also grew exponentially in the mid-1900s after strict poaching controls were put in place.[15]

.

dN(t)/dt = rate of change of population density

N(t) = population size at time t

r = per capita growth rate

K = carrying capacity

.JPG.webp)

The logistic growth equation is an effective tool for modelling intraspecific competition despite its simplicity, and has been used to model many real biological systems. At low population densities, N(t) is much smaller than K and so the main determinant for population growth is just the per capita growth rate. However, as N(t) approaches the carrying capacity the second term in the logistic equation becomes smaller, reducing the rate of change of population density.[16]

The logistic growth curve is initially very similar to the exponential growth curve. When population density is low, individuals are free from competition and can grow rapidly. However, as the population reaches its maximum (the carrying capacity), intraspecific competition becomes fiercer and the per capita growth rate slows until the population reaches a stable size. At the carrying capacity, the rate of change of population density is zero because the population is as large as possible based on the resources available.[4] Experiments on Daphnia growth rates showed a striking adherence to the logistic growth curve.[17] The inflexion point in the Daphnia population density graph occurred at half the carrying capacity, as predicted by the logistic growth model.

Gause’s 1930s lab experiments showed logistic growth in microorganisms. Populations of yeast grown in test tubes initially grew exponentially. But as resources became scarcer, their growth rates slowed until reaching the carrying capacity.[3] If the populations were moved to a larger container with more resources they would continue to grow until reaching their new carrying capacity. The shape of their growth can be modeled very effectively with the logistic growth model.

See also

- Competition (biology)

- Interspecific competition

- Logistic model

- Plant density

- Population ecology

- Sexual dimorphism

- Sexual selection

- Female intrasexual competition

- War – extreme result of intraspecific competition in humans

References

- Townsend (2008). Essentials of Ecology. pp. 103–105. ISBN 978-1-4051-5658-5.

- Connell, Joseph (November 1983). "On the prevalence and relative importance of interspecific competition: evidence from field experiments" (PDF). American Naturalist. 122 (5): 661–696. doi:10.1086/284165. S2CID 84642049. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-26.

- Gause, Georgy (October 1932). "Experimental studies on the struggle for existence". Journal of Experimental Biology. 9 (4): 389–402.

- Keddy, Paul (2001). Competition. Dordrecht. ISBN 978-1402002298.

- Nishikawa, Kiisa (1985). "Competition and the evolution of aggressive behavior in two species of terrestrial salamanders" (PDF). Evolution. 39 (6): 1282–1294. doi:10.2307/2408785. JSTOR 2408785. PMID 28564270.

- Perdue, Bonnie M.; Gaalema, Diann E.; Martin, Allison L.; Dampier, Stephanie M.; Maple, Terry L. (2010-02-22). "Factors affecting aggression in a captive flock of Chilean flamingos (Phoenicopterus chilensis)". Zoo Biology. 30 (1): 59–64. doi:10.1002/zoo.20313. PMID 20186725.

- Wise, David; Wagner (August 1992). "Evidence of exploitative competition among young stages of the wolf spider Schizocosa ocreata". Oecologia. 91 (1): 7–13. doi:10.1007/BF00317234. PMID 28313367. S2CID 19268804.

- Connell, Joseph (1990). Perspectives on Plant Competition. The Blackburn Press. pp. 9–23. ISBN 978-1930665859.

- Norbury, Grant (December 2001). "Conserving dryland lizards by reducing predator-mediated apparent competition and direct competition with introduced rabbits". Journal of Applied Ecology. 38 (6): 1350–1361. doi:10.1046/j.0021-8901.2001.00685.x.

- Vogel, Erin (August 2005). "Rank differences in energy intake rates in white-faced capuchin monkeys, Cebus capucinus: the effects of contest competition". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 58 (4): 333–344. doi:10.1007/s00265-005-0960-4. JSTOR 25063623. S2CID 29039152.

- Olsson, Mats; Schwartz, Tonia; Uller, Tobias; Healey, Mo (February 2009). "Effects of sperm storage and male colour on probability of paternity in a polychromatic lizard". Animal Behaviour. 77 (2): 419–424. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.10.017. S2CID 53164664.

- Madsen, Thomas; Shine, Richard (1993). "Temporal variability in sexual selection acting on reproductive tactics and body size in male snakes". The American Naturalist. 141 (1): 166–171. doi:10.1086/285467. JSTOR 2462769. PMID 19426025. S2CID 2390755.

- Le Bouef, Burney (1974). "Male-male Competition and Reproductive Success in Elephant Seals". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 14 (1): 163–176. doi:10.1093/icb/14.1.163.

- Crawley, Mick; Gillman (April 1990). "A comparative evaluation of models of cinnabar moth dynamics". Oecologia. 82 (4): 437–445. doi:10.1007/BF00319783. PMID 28311465. S2CID 9288133.

- Young, Kim; Ferreira, Van Aarde (March 2009). "The influence of increasing population size and vegetation productivity on elephant distribution in the Kruger National Park". Austral Ecology. 34 (3): 329–342. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2009.01934.x.

- Hanson, Floyd (1981). "Logistic growth with random density independent disasters". Theoretical Population Biology. 19 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1016/0040-5809(81)90032-0.

- Schoener, Thomas (March 1973). "Population growth regulated by intraspecific competition for energy or time: Some simple representations". Theoretical Population Biology. 4 (1): 56–84. doi:10.1016/0040-5809(73)90006-3. PMID 4726010.