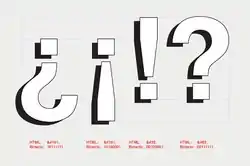

Inverted question and exclamation marks

Inverted question mark, ¿, and inverted exclamation mark, ¡, are punctuation marks used to begin interrogative and exclamatory sentences (or clauses), respectively, in written Spanish (both in Spain and Latin America) and sometimes also in languages which have cultural ties with Spain, such as the Galician, Asturian and Waray languages.[1]

| ¿ ¡ | |

|---|---|

Inverted question mark Inverted exclamation mark | |

| In Unicode | U+00BF ¿ INVERTED QUESTION MARK (HTML ¿ · ¿)U+00A1 ¡ INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK (HTML ¡ · ¡) |

.jpg.webp)

The initial marks are normally mirrored at the end of the sentence or clause by the 'ordinary' question mark, ?, or exclamation mark, !, used in most other languages. Unlike the ending marks, which are printed along the baseline of a sentence, the inverted marks (¿ and ¡) descend below the line.

Inverted marks were originally recommended by the Real Academia Española (Royal Spanish Academy) in 1754, and adopted gradually over the next century.

On computers, inverted marks are supported by various standards, including ISO-8859-1, Unicode, and HTML. They can be entered directly on keyboards designed for Spanish-speaking countries, or via alternative methods on other keyboards.

Usage

The inverted question mark, ¿, is a punctuation mark written before the first letter of an interrogative sentence or clause to indicate that a question follows. It is a rotated form of the standard symbol "?" recognized by speakers of other languages written with the Latin alphabet. Inverted punctuation is especially critical in Spanish since the syntax of the language means that both statements and questions or exclamations could have the same wording.[2]

In most languages, a single question mark is used, and only at the end of an interrogative sentence: "How old are you?" This was once true of the Spanish language. Spanish does retain this ending question mark as well as the initial inverted question mark.

Adoption

The inverted question mark was adopted long after the Real Academia's decision, published in the second edition of the Ortografía de la lengua castellana (Orthography of the Castilian language) in 1754[3] recommending it as the symbol indicating the beginning of a question in written Spanish—e.g. "¿Cuántos años tienes?" ("How old are you?"). The Real Academia also ordered the same inverted-symbol system for statements of exclamation, using the symbols "¡" and "!". This helps to recognize questions and exclamations in long sentences. "Do you like summer?" and "You like summer." are translated respectively as "¿Te gusta el verano?" and "Te gusta el verano." (There is not always a difference between the wording of a yes–no question and the corresponding statement in Spanish.) These new rules were slowly adopted; there are 19th-century books in which the writer uses neither "¡" nor "¿".

In sentences that are both declarative and interrogative, the clause that asks a question is isolated with the starting-symbol inverted question mark, for example: "Si no puedes ir con ellos, ¿quieres ir con nosotros?" ("If you cannot go with them, would you like to go with us?"), not "¿Si no puedes ir con ellos, quieres ir con nosotros?"

Some writers omit the inverted question mark in the case of a short unambiguous question such as: "Quién viene?" ("Who comes?"). This is the criterion in Galician[4] and Catalan.[5] Certain Catalan-language authorities, such as Joan Solà i Cortassa, insist that both the opening and closing question marks be used for clarity.

Some Spanish-language writers, among them Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda (1904–1973), refuse to use the inverted question mark.[6] It is common in Internet chat rooms and instant messaging now to use only the single "?" as an ending symbol for a question, since it saves typing time. Multiple closing symbols are used for emphasis: "Por qué dices eso??", instead of the standard "¿Por qué dices eso?" ("Why do you say that?"). Some may also use the ending symbol for both beginning and ending, giving "?Por qué dices eso?" Given the informal setting, this might be unimportant; however, teachers see this as a problem, fearing and claiming that contemporary young students are inappropriately and incorrectly extending the practice to academic homework and essays. (See Internet linguistics § Educational perspective)

History

In 1668, John Wilkins proposed using the inverted exclamation mark "¡" as a symbol at the end of a sentence to denote irony. He was one of many, including Desiderius Erasmus, who felt there was a need for such a punctuation mark, but Wilkins' proposal, as was true of the other attempts, failed to take hold.[7][8]

Mixtures

It is acceptable in Spanish to begin a sentence with an opening inverted exclamation mark ("¡") and end it with a question mark ("?"), or vice versa, for statements that are questions but also have a clear sense of exclamation or surprise such as: ¡Y tú quién te crees? ("And who do you think you are?!"). Normally, four signs are used, always with one type in the outer side and the other in the inner side (nested) (¿¡Y tú quién te crees!?, ¡¿Y tú quién te crees?![9])

Unicode 5.1 also includes U+2E18 ⸘ INVERTED INTERROBANG, which is an inverted version of the interrobang (also known as a "gnaborretni"[note 1] (/ŋˌnɑːbɔːrˈɛt.ni/)), a nonstandard punctuation mark used to denote both excitement and a question in just one glyph.

Computer usage

Encodings

¡ and ¿ are both located within the Unicode Common block, and are both inherited from ISO-8859-1:

- U+00A1 ¡ INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK

- U+00BF ¿ INVERTED QUESTION MARK

The characters also appear in most extended ASCII encodings.

In Windows, an inverted question mark is valid in a file or directory name, whereas the normal question mark is a reserved character which cannot be used.

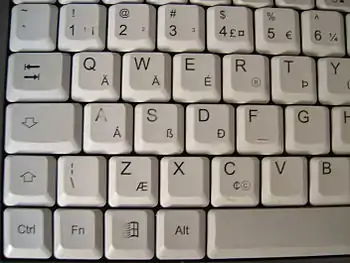

Typing the character

¿ and ¡ are available in all keyboard layouts for Spanish-speaking countries. Smart phones typically offer these if you hold down ? or ! in the on-screen keyboard. Auto-correct will often turn a normal mark typed at the start of a sentence to the inverted one.

| ¡ | ¿ | |

|---|---|---|

| Windows | Alt+173 Alt+0161 |

Alt+168 Alt+0191 |

| Microsoft Word | Ctrl+Alt+⇧ Shift+1 | Ctrl+Alt+⇧ Shift+/ |

| International keyboards | AltGr+1 | AltGr+/ |

| Linux | Compose!! Ctrl+⇧ Shift+uA1 |

Compose?? Ctrl+⇧ Shift+uBF |

| macOS | ⌥ Option+1 | ⌥ Option+⇧ Shift+/ |

| HTML | ¡ ¡ | ¿ ¿ |

| LaTeX | !` \textexclamdown |

?` \textquestiondown |

See also

Notes

- Interrobang spelled backwards.

References

- De Veyra, Vicente I. (1982). "Ortograpiya han Binisaya". Kandabao: Essays on Waray language, literature, and culture.

- Rosetta Stone Inc. (September 5, 2019). "What's Up With The Upside Down Question Mark?". rosettastone.com. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Ediciones de la Ortografía Académica" [Editions of the Academic Orthography] (PDF). Real Academia Española.

- "7. Os signos de interrogación e de admiración" (PDF). Normas ortográficas e morfolóxicas do idioma galego [Orthographic rules and morphology of the Galician language] (in Galician) (23ª ed.). Real Academia Galega. 2012. p. 38. ISBN 978-84-87987-78-6. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

Para facilitar a lectura e evitar ambigüidades pode-rase indicar o inicio destas entoacións cos signos ¿ e ¡, respectivamente.

- Institut d'Estudis Catalans (1996), "Els signes d'interrogació i d'admiració (Acord de l'11 de juny de 1993)", Documents de la Secció Filològica, III, pp. 92–94, archived from the original on 2011-09-06

- Pablo Neruda, "Antología Fundamental". Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. (556 KB), (June 2008). ISBN 978-956-16-0169-7. p. 7 (in Spanish)

- Houston, Keith (24 September 2013). Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks. W. W. Norton. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-393-24154-9.

- Popova, Maria. "Ironic Serif: A Brief History of Typographic Snark and the Failed Crusade for an Irony Mark". Brain Pickings. Retrieved 1 Sep 2014.

- RAE's (in Spanish)