Iron Gates

The Iron Gates (Romanian: Porțile de Fier; Serbian: Ђердапска клисура / Đerdapska klisura or Гвоздена врата / Gvozdena vrata; Bulgarian: Железни врата, romanized: Zhelezni vrata; German: Eisernes Tor; Hungarian: Vaskapu) is a gorge on the river Danube. It forms part of the boundary between Serbia (to the south) and Romania (north). In the broad sense it encompasses a route of 134 km (83 mi); in the narrow sense it only encompasses the last barrier on this route, just beyond the Romanian city of Orșova, that contains two hydroelectric dams, with two power stations, Iron Gate I Hydroelectric Power Station and Iron Gate II Hydroelectric Power Station.

At this point in the Danube, the river separates the southern Carpathian Mountains from the northwestern foothills of the Balkan Mountains. The Romanian side of the gorge constitutes the Iron Gates Natural Park, whereas the Serbian part constitutes the Đerdap National Park. A wider protected area on the Serbian side was declared the UNESCO global geopark in July 2020.[1][2]

Archaeologists have named the Iron Gates mesolithic culture, of the central Danube region circa 13,000 to 5,000 years ago, after the gorge. One of the most important archaeological sites in Serbia and Europe is Lepenski Vir, the oldest planned settlement in Europe, located on the banks of the Danube in the Iron Gate gorge.[3]

Toponymy

In English, the gorge is known as Iron Gates or Iron Gate. An 1853 article about the Danube in The Times of London referred to it as "the Iron Gate, or the Gate of Trajan."[4]

In languages of the region including Romanian, Hungarian, Polish, Slovak, Czech, German, and Bulgarian, names literally meaning "Iron Gates" are used to name the entire range of gorges. These names are Romanian: Porțile de Fier (pronounced [ˈport͡sile de ˈfjer]), Hungarian: Vaskapu, Slovak: Železné vráta, Polish: Żelazne Wrota, German: Eisernes Tor, and Bulgarian: Железни врата Železni vrata. An alternative Romanian name for the last part of the route is Defileul Dunării, literally "Danube Gorge".

In Serbian, the gorge is known as Đerdap (Ђердап; [d͡ʑě̞rdaːp]), with the last part named Đerdapska klisura (Ђердапска клисура; [d͡ʑě̞rdaːpskaː klǐsura], meaning Đerdap Gorge) from the Byzantine Greek Κλεισούρα (kleisoura), "enclosure" or "pass."

Both Đerdap and former Serbian name for it, Demir-kapija, are Turkish in origin. Demir-kapija means "iron gate" (demirkapı) and a translation of it entered most of the other languages as the name of the gorge, while đerdap comes from girdap which means whirlpool, vortex.[5]

Natural physical features

Gorges

The first narrowing of the Danube lies beyond the Romanian isle of Moldova Veche and is known as the Golubac gorge. It is 14.5 km long and 230 m (755 ft) wide at the narrowest point. At its head, there is a medieval fort at Golubac, on the Serbian bank. Through the valley of Ljupovska lies the second gorge, Gospodjin Vir, which is 15 km long and narrows to 220 m (722 ft). The cliffs scale to 500 m and are the most difficult to reach here from land. The broader Donji Milanovac forms the connection with the Great and the Small Kazan gorge, which have a combined length of 19 km (12 mi). The Orșova valley is the last broad section before the river reaches the plains of Wallachia at the last gorge, the Sip gorge.

The Great Kazan (kazan meaning "cauldron" or "reservoir") is the most famous and the most narrow gorge of the whole route: the river here narrows to 150 m and reaches a depth of up to 53 m (174 ft).

Navigation and channels

The riverbed rocks and the associated rapids made the gorge valley an infamous passage for shipping, even for the most seasoned boatmen. During the period of the Ottoman rule, the ships were guided through by the local navigators, familiar with the routes, called kalauz (from Turkish kalavuz, meaning guide, travel leader). During the rule of prince Miloš Obrenović, local Serbs gradually took over from the Ottomans, being officially appointed by the prince. In order not to aggravate the Ottomans further, the prince named Serbian navigators by a Turkish name, dumendžibaša, from dümen (rudder) and baş (head, chief, master). The navigation fee was divided among dumendžibaša, loc (river pilots) and regional municipalities.[6]

In German, the passage is still known as the Kataraktenstrecke, even though the cataracts are gone. Near the actual "Iron Gates" strait the Prigrada rock was the most important obstacle (until 1896): the river widened considerably here and the water level was consequently low. Upstream, the Greben rock near the "Kazan" gorge was notorious.

Some of the channels created included:[7]

- Stenka, 1,900 m (6,200 ft) long, with 10 navigational signals (originally, the balloons were used)

- Izlaz-Tahatlija, 2,351 m (7,713 ft), with 7 signals

- Svinița, 1,200 m (3,900 ft), with 4 signals

- Juc, 1,260 m (4,130 ft), with 5 signals

- Sip, 4,375 m (14,354 ft)

- Mali Đerdap, 1,050 m (3,440 ft), as an extension of Sip Channel

In total, 15,465 m (50,738 ft) of navigable channels was created.[7] They were flooded when the artificial Lake Đerdap was created (early 1970s). The results of these efforts were slightly disappointing. The currents in the Sip Channel were so strong at 15kts (8 m/s) that until 1973, ships had to be dragged upstream along the canal by locomotive. The Iron Gates thus remained an obstacle of note.[7][8][9]

Dams

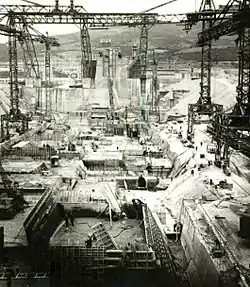

The construction of the joint Romanian-Yugoslavian mega project commenced in 1964. In 1972 the Iron Gate I Dam was opened, followed by Iron Gate II Dam, in 1984, along with two hydroelectric power stations, two sluices and navigation locks for shipping.

The construction of these dams gave the valley of the Danube below Belgrade the nature of a reservoir, and additionally caused a 35 m rise in the water level of the river near the dam. The old Orșova, the Danube island of Ada Kaleh (below) and at least five other villages, totaling a population of 17,000, had to make way. People were relocated and the settlements have been lost forever to the Danube.

When designed and built without adequate attention to the natural functioning of a river, dams have the effect of cutting a river into ecologically isolated compartments, which do not allow free movement and migration of species.[10] Migratory fish are particularly badly hit, being rendered unable to move upstream or downstream between their spawning grounds and areas used at other times in their life cycle. The construction of the Iron Gates had a major impact on the local fauna and flora as well—for example, the spawning routes of several species of sturgeon were permanently interrupted. Beluga sturgeon was the largest, and the largest specimen was recorded in 1793, at 500 kg (1,100 lb).[11] There have also been significant regional economic impacts – notably on the productivity of Danube fisheries.[12] The status of the Danube’s migratory fish species is a strong indicator of the ecological health of the entire Danube River Basin, which in turn has wider economic and strategic consequences.

The flora and fauna, as well as the geomorphological, archaeological and cultural historical artifacts of the Iron Gates have been under the protection of both nations since the construction of the dam. In Serbia this was done with the Đerdap National Park (since 1974, 636.08 km2 (245.59 sq mi)) and in Romania by the Porțile de Fier National Park (since 2001, 1,156.55 km2 (446.55 sq mi)).

History

Prehistoric and Roman era

Sandstone statues dated to the early Neolithic era indicate that the area has been inhabited for a very long time. Even more significant are the Iron Gates Mesolithic (c. 13,000 to 5,000 BP) sites – in particular, the gorge of Gospodjin Vir, which contains the major archaeological site of Lepenski Vir (unearthed in the 1960s). Lepenski Vir is often regarded as the most important Mesolithic site in south-east Europe.

East of the Great Kazan the Roman emperor Trajan built the legendary bridge erected by Apollodorus of Damascus. Construction of the bridge ran from 103 through 105, preceding Trajan's final conquest of Dacia. (On the right (Serbian) bank a Roman plaque commemorates him. On the Romanian bank, at the Small Kazan, a likeness of Decebalus, Trajan's Dacian opponent, was carved in rock in 1994–2004.)

Ada Kaleh

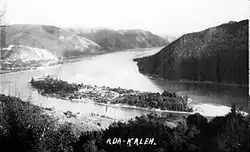

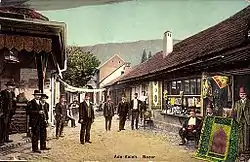

Perhaps the most evocative consequence of the Đerdap dam's construction was the flooding of an islet named Ada Kaleh. A former Turkish exclave, it had a mosque and a thousand twisting alleys, and was known as a free port and smuggler's nest. Many other ethnic groups lived there beside Turks.

The island was about 3 km (1.9 mi) downstream from Orșova and measured 1.7 by 0.4-0.5 km. It was walled; the Austrians built a fort there in 1669 to defend it from the Turks, and that fort would remain a bone of contention for the two empires. In 1699 the island came under Turkish control, from 1716 to 1718 it was Austrian, after a four-month siege in 1738 it was Turkish again, followed by the Austrians reconquering it in 1789, only to have to yield it to the Turks in the following peace treaty.

Thereafter, the island lost its military importance. The 1878 Congress of Berlin forced the Ottoman Empire to retreat far into the south, but the island remained the property of the Turkish sultan, allegedly because the treaty neglected to mention it. The inhabitants enjoyed exemption from taxes and customs and were not conscripted. In 1923, when the Ottoman monarchy had disappeared, the island was given to Romania in the Treaty of Lausanne.

The Ada Kaleh mosque dated from 1903 and was built on the site of an earlier Franciscan monastery. The mosque's carpet, a gift from the Turkish sultan Abdülhamid II, has been located in the Constanța mosque since 1965.

Most Ada Kaleh inhabitants emigrated to Turkey after the evacuation of the island. A smaller part went to Northern Dobruja, another Romanian territory with a Turkish minority.

19th century's Hungarian initiatives

By the early 19th century, freedom of navigation on the Danube was regarded as important by many different states in the region and beyond. Allowing passage through the Iron Gates by larger vessels had become a priority. By 1831 a plan had been drafted to make the passage navigable, at the initiative of Hungarian politician István Széchenyi. Not being satisfied with the solutions compiled by the Austrio-Hungarian government and the Austro-Turkish commission, the government of Hungary formed its own commission for the organization of the navigation through the Iron Gates. The project was finished in 1883. Appointed in 1883 and again in 1886, Minister of Trade and Transportation Gábor Baross, Hungary's "Iron Minister", presided over modernization projects at Hungary's sea port in Fiume (Rijeka), and regulation of the Upper Danube and Iron Gate.[13]

Works on the gorge section were done by the Hungarian Technical Administration over 11 years from 1889. The works were divided in two sectors, the upper and the lower Iron Gates. The channels in the upper section, at the town of Orșova (the tripoint between Austria-Hungary, Romania and Serbia at the time) were up to 60 m (197 ft) wide and 2 m (7 ft) deep, at the zero water level in Orșova. In the southern section, the channels were 60 m (197 ft) wide and 3 m (10 ft) deep, except for the Sip Channel, which was 73 m (240 ft) wide.[7] In 1890, near Orșova, the last border town of Hungary, rocks were cleared by explosion over a 2 km (1.2 mi) stretch in order to create channels. A spur of the Greben Ridge was removed across a length of over 2 km (1.2 mi). Here, a depth of 2 m (7 ft) sufficed. On 17 September 1896, the Sip Channel thus created (named after the Serbian Sip village on the right bank) was inaugurated by the Austro-Hungarian emperor Franz Joseph, the Romanian king Carol I, and the Serbian king Alexander Obrenovich.[7][8][9]

Cultural references to the Iron Gates

Literature

- A plan to blow up the Iron Gates gorge and thereby block the Danube grain trade is included in the proposed acts of sabotage in the Balkan Trilogy section of the Fortunes of War novels (1960-1980) by Olivia Manning. A similar plot device, to prevent oil barges reaching Nazi Germany, is used by Dennis Wheatley in his 1946 Duke de Richleau novel, Codeword: Golden Fleece.

- Two novels – The Valley of Horses (1982) and The Plains of Passage (1990) – in Jean M. Auel's series Earth's Children focus on the difficulties of prehistoric people traveling through or around the Iron Gates in both during scene sequences detailing travel adventures whilst the protagonists navigate between the upper and lower Danube valleys.

- The 1986 book Between the Woods and the Water, by travel writer Patrick Leigh Fermor, describes a night on the now submerged island Ada Kaleh and a trip by ferry through the Iron Gates, in August, 1934.

Film

- The 2003 film Donau, Duna, Dunaj, Dunav, Dunarea contains several minutes of film of the Iron Gates.

Music

- The Iron Gates are mentioned in the second verse of the Zvonko Bogdan song Rastao sam pored Dunava.

- The folk song Jugoslavijo by Milutin Popović, commonly called Od Vardara pa do Triglava, includes a mention of the Iron Gates in the beginning.

Gallery

Ponicova cave

Ponicova cave Mraconia Monastery

Mraconia Monastery.jpg.webp)

See also

- Tourism in Romania

- Seven Wonders of Romania

- Commissions of the Danube River – International river management bodies

- Danube River Conference of 1948 – International diplomatic meeting

- Defile (geography) – A narrow pass or gorge between mountains or hills

- Energy in Romania

References

- https://plus.google.com/+UNESCO (2020-07-10). "UNESCO designates 15 new Geoparks in Asia, Europe, and Latin America". UNESCO. Retrieved 2020-07-13.

- Dimitrije Bukvić (19 July 2020). "Đerdap – prvi srpski geopark" [Đerdap – first Serbian geopark]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 9.

- Sormaz, Andela (5 May 2020). "Lepenski Vir". ancient.eu. Ancient History Encyclopedia Limited. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

The overall architecture at Lepenski Vir is of a specific shape with all the houses built according to a plan.

- "The Seat of War on the Danube," The Times, December 29, page 8

- Dimitrije Bukvić (3 July 2017), "Mitovi i legende iza gvozdenih vrata" [Myths and legends from behind the iron doors], Politika (in Serbian), p. 08

- "Да ли знате: Како су некада звали спроводнике лађа на Ђердапу?" [Do you know: how the Đerdap navigators were used to be called?]. Politika (in Serbian). 31 January 2018. p. 32.

- "Da li znate? - Kada je regulisana plovidba kroz đerdapski sektor?" [Do you know? - When was the navigation through the Iron Gates sector regulated?], Politika (in Serbian), p. 30, 8 October 2017

- "Sipska lokomotiva i locovi na Dunavu" [Sip locomotive and locs on the Danube] (in Serbian). Biblioteka Centar za Kulturu Kladovo. 4 December 2015.

- Miroslav Stefanović (14 January 2018). "Политикин времеплов: Како је Сипским каналом укроћен Дунав" [Politika's chronicle: How the Sip Canal tamed the Danube]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1059 (in Serbian). pp. 28–29.

- Claudio Comoglio (2011). "FAO Scoping mission at Iron Gates I and II dams (Romania and Serbia). Preliminary assessment of the feasibility for providing free passage to migratory fish species" (PDF).

- Miroslav Stefanović (22 April 2018). "Мегдани аласа и риба грдосија" [Fights between the fishermen and the giant fishes]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1073 (in Serbian). pp. 28–29.

- Holcik, Juraj (1989). The freshwater fishes of Europe Vol.I Part II General introduction to fishes. Wiesbaden: Aula Verlag.

- "THE HISTORY OF PASSENGER NAVIGATION IN HUNGARY MFTR (1895) - MAHART (1955) - MAHART PassNave (1994)". MAHART PassNave. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

Further reading

- Bonsall, Clive; Lennon, Rosemary; McSweeney, Kathleen; Stewart, Catriona; Harkness, Douglas; Boronean, Vasile; Bartosiewicz, László; Payton, Robert; Chapman, John (1997). "Mesolithic and Early Neolithic in the Iron Gates: A Paiaeodietary Perspective". Journal of European Archaeology. 5 (1): 50–92. doi:10.1179/096576697800703575. Archived from the original on 2013-01-26.

- Bonsall, C; Cook, G T; Hedges, R E M; Higham, T F G; Pickard, C; Radovanović, I (2004). "Radiocarbon and stable isotope evidence of dietary change from the Mesolithic to the Middle Ages in the iron gates: New results from Lepenski Vir". Radiocarbon. 46 (1): 293–300. doi:10.1017/S0033822200039606.

- Teodoru, Cristian; Wehrli, Bernhard (2005). "Retention of Sediments and Nutrients in the Iron Gate I Reservoir on the Danube River". Biogeochemistry. 76 (3): 539–65. doi:10.1007/s10533-005-0230-6. hdl:20.500.11850/57912.

- Micić, Vesna; Kruge, Michael; Körner, Petra; Bujalski, Nicole; Hofmann, Thilo (2010). "Organic geochemistry of Danube River sediments from Pančevo (Serbia) to the Iron Gate dam (Serbia–Romania)". Organic Geochemistry. 41 (9): 971–4. doi:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2010.05.008.

- Roksandic, Mirjana; Djurić, Marija; Rakočević, Zoran; Seguin, Kimberly (2006). "Interpersonal violence at Lepenski Vir Mesolithic/Neolithic complex of the Iron Gates Gorge (Serbia-Romania)". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 129 (3): 339–48. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20286. PMID 16323188.

- Boric, Dusan; Miracle, Preston (2004). "Mesolithic and Neolithic (Dis)Continuities in the Danube Gorges: New Ams Dates from Padina and Hajducka Vodenica (Serbia)". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 23 (4): 341–71. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.2004.00215.x.

- Bonsall, Clive (2008). "The Mesolithic of the Iron Gates". In Bailey, Geoff; Spikins, Penny (eds.). Mesolithic Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 238–79. ISBN 978-0-521-85503-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iron Gate (Danube). |

- (in Romanian) Porțile de Fier National Park

- (in Serbian) Iron Gates in 1965 on YouTube

- (in Serbian) Lepenski Vir

- (in German) Ada Kaleh, die Inselfestung, also the source of the Ada Kaleh section in this article