Isolichenan

Isolichenan, also known as isolichenin, is a cold-water soluble α-glucan occurring in certain species of lichens. It was first isolated as a component of an extract of Iceland moss in 1813, along with lichenin. After further analysis and characterization of the individual components of the extract, isolichenan was named in 1881. It is the first α-glucan to be described from lichens. The presence of isolichenan in the cell walls is a defining characteristic in several genera of the lichen family Parmeliaceae. Although most prevalent in that family, it has also been isolated from members of the families Ramalinaceae, Stereocaulaceae, Roccellaceae, and Lobariaceae. Experimental studies have shown that isolichenan is produced only when the two lichen components – fungus and alga – are growing together, not when grown separately. The biological function of isolichenan in the lichen thallus is unknown.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Isolichenin; (1→3)&(1→4) α-D-glucan | |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| Properties | |

| (C6H10O5)x | |

| Molar mass | Variable |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Early studies

Isolichenan was first isolated from Cetraria islandica in 1813 by Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius,[1] who also at the same time isolated the cellulose-like hot-water soluble glucan lichenan. Because in these experiments the isolichenan component of the lichen extract had a positive reaction with iodine staining (i.e. production of a blue colour), Berzelius thought it to be similar in nature to starch, and he called it "lichen starch".[2] It was thought to function as a reserve food source for the organism.[3] Later studies showed it to be a mixture of polysaccharides. In 1838,[4] Gerardus Johannes Mulder isolated the blue-staining component of the C. islandica extract, believing it to be starch.[2] Friedrich Konrad Beilstein gave the name "isolichenan" to this substance in 1881.[5] Isolichenan was the first α-glucan described from lichens.[6]

In 1947, Kurt Heinrich Meyer and P. Gürtler, discussing the preparation of lichenan, reported that the mother liquor contained a water-soluble glucan that could be purified by repeated freezing and thawing. In this process, which completely removed lichenan, they obtained isolichenan in a 0.55% yield.[7]

Structure

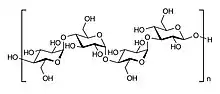

Isolichenan is a polymer of glucose units joined by a mixture of α-(1→3) and α-(1→4) linkages. Using the technique of partial acid hydrolysis, Stanley Peat and colleagues determined that the linkages are of the α-configuration.[5] The ratio of these linkages has been reported differently by various authors in the scientific literature: 11:9,[5] 3:2,[8] 2:1,[9] 3:1,[10] and 4:1.[11] Fleming and Manners found the ratio to be 56.5:43.5 and 57:43 in two separate experiments using the Smith degradation procedure. This technique uses the successive steps of periodate oxidation, borohydride reduction and mild acid hydrolysis in which acetal (but not glucosidic linkages), are hydrolysed.[12] The distribution of linkages was found to be somewhat irregular, with both types occurring in groups of two or more in at least some areas;[5] another study suggests that isolichenan has mostly groups of one or two α-(1→3) bonds surrounded by α-(1→4) bonds.[13] The relatively weak intensity of the iodine-staining reaction of isolichenan, compared with for example amylose (a linear α-(1→4)-linked glucan and the major component of starch), is thought to be a result of its preponderance of (1→3) linkages. This reduces the formation of the polyiodide-complex that gives the positive reaction its blue colour.[3]

The chain length of isolichenan was estimated at 42–44 glucose units.[8] The reported molecular weight of isolichenan also varies, from 26 kD[11] to 2000 kD.[9] The relatively short chain length of isolichenan may explain why it is soluble in cold water after it has been extracted from the lichen thallus.[3] Purified isolichenan has a high positive specific rotation in water. It has been reported as high as +272,[5] although different sources give differing values.[6]

The term "isolichenan-type" has been used as a general term for α-D-glucans having (1→3)-(1→4) linkages in their main chain.[6] Similar to isolichenan, the α-D-glucan known as Ci-3 consists of 1→3 and 1→4 linked α-D-glucose residues in ratio of 2:1, but with a much higher degree of polymerization and a molecular weight of about 2000 kD. It is also found in Cetraria islandica.[9] As the discrepancies in reported values demonstrate, lichens produce isolichenan-type polysaccharides with considerable variation in linkage ratios as well as molecular weight, even within the same species.[6]

The carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum of isolichenan was reported by Yokota and colleagues in 1979[14] and also by Gorin and Iacomini in 1984.[15]

Occurrence

Since its discovery in Cetraria islandica, isolichenan has been isolated from many other lichen species. It is predominant in the Parmeliaceae, a large and diverse family of the class Lecanoromycetes. Parmeliaceae genera and species containing isolichenan include: Alectoria (A. sulcata, A. sarmentosa); Cetraria (Cetraria cucullata, C. islandica, C. nivaris, C. richardsonii; Evernia (E. prunastri); Letharia (L. vulpina); Neuropogon (N. aurantiaco-ater); Parmelia (P. caperata, P. cetrarioides, P. conspersa, P. hypotrypella, P. laevior, P. nikkoensis, P. saxatilis, P. tinctorum); Parmotrema (P. cetrarum, P. araucaria, P. sulcata); and Usnea (U. barbata, U. baylei, U. faciata, U. longissima, U. meridionalis, U. rubescens). A few members of the family Ramalinaceae have been shown to contain isolichenan, including Ramalina celastri, R. ecklonii, R. scopulorum, and R. usnea. In the family Stereocaulaceae, isolichenan has been isolated from S. excutum, S. japonicum, and S. sorediiferum. It is also known to occur in single species in the Roccellaceae (Roccella montagnei) and the Lobariaceae (Pilophoron ocicularis).[6]

Uses

Although isolichenan is not nearly as constant at the genus level as lichenan,[3] the presence of isolichenan in the cell walls is a defining character in several genera of the lichen family Parmeliaceae, including Asahinea, Cetrelia, Flavoparmelia, and Psiloparmelia.[16] In contrast, the absence of isolichenan is a character of genus Xanthoparmelia.[3]

Isolichenan is used as an active ingredient in cough lozenges as a component of Cetraria islandica extract.[17]

Research

Isolichenan was shown to enhance hippocampal plasticity and behavioural performance in rats.[18] When administered orally, isolichenan was also shown to improve memory acquisition in mice impaired by ethanol, as well as in rats in which memory impairment had been induced by beta-amyloid peptide.[19][18] In more recent research, isolichenan was shown to improve cognitive function in healthy adults.[20][21]

The main α-glucan synthesized by lichens of the genus Ramalina in the symbiotic state is isolichenan. A series of experiments have shown, however, that it is not produced by either individual symbiont when cultivated apart from each other.[22][23][24] Its absence in this circumstance suggests that it may not have an importance as a structural part of the fungal cell wall; this contrasts with lichenan, where the (1→3)(1→4)-β-glucan has been shown to be involved in cell wall structure.[25] Isolichenan is synthesized by the mycobiont only in the presence of its symbiotic partner (the green alga Trebouxia) in a special microenvironment – the lichen thallus. The triggering of this phenomenon and the biological function of isolichenan in the symbiotic relationship between fungi and algae is still unknown.[26] In a study on the immunomodulatory effects of an aqueous Cetraria islandica extract, it was shown that the extract was able to upregulate the secretion of the cytokine interleukin 10. However, when the individual components of this extract (including lichenan, isolichenan, protolichesterinic and fumarprotocetraric acids) were tested with the same assay, isolichenan had no anti-inflammatory effects (only lichenan did).[27]

References

- Berzelius, Jöns Jacob. "Versuche über die Mischung des Isländischen Mooses und seine Anwendung als Nahrungsmittel". Schweigger's Journal für Chemie und Physik (in German). 7: 317–352.

- Smith, Anne L. (1920). Lichens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 210.

- Common, Ralph S. (1991). "The distribution and taxonomic significance of lichenan and isolichenan in the Parmeliaceae (lichenized Ascomycotina), as determined by iodine reactions. I. Introduction and methods. II. The genus Alectoria and associated taxa". Mycotaxon: 67–112.

- Mulder, G.J. (1838). "Ueber das Inulin und die Moosstärke". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 15 (1): 299–302. doi:10.1002/prac.18380150128.

- Peat, Stanley; Whelan, W. J.; Turvey, J. R.; Morgan, K. (1961). "125. The structure of isolichenin". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 623–629. doi:10.1039/jr9610000623.

- Olafsdottir, Elin S.; Ingólfsdottir, Kristín (2001). "Polysaccharides from Lichens: Structural Characteristics and Biological Activity". Planta Medica. 67 (3): 199–208. doi:10.1055/s-2001-12012. PMID 11345688.

- Meyer, Kurt H.; Gürtler, P. "Recherches sur l'amidon. XXXII. L'isolichenine". Helvetica Chimica Acta (in French). 30 (3): 761–765. doi:10.1002/hlca.19470300308.

- Chanda, N.B.; Hirst, E.L.; Manners, D.J. (1957). "375. A comparison of isolichenin and lichenin from Iceland moss (Cetraria islandica)". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 1951. doi:10.1039/jr9570001951.

- Olafsdottir, E.S.; Ingolfsdottir, K.; Barsett, H.; Smestad Paulsen, B.; Jurcic, K.; Wagner, H. (1999). "Immunologically active (1→3)-(1→4)-α-D-glucan from Cetraria islandica". Phytomedicine. 6 (1): 33–39. doi:10.1016/S0944-7113(99)80032-4.

- Stuelp, P.M; Carneiro Leão, A.M.A; Gorin, P.A.J.; Iacomini, M. (1999). "The glucans of Ramalina celastri: relation with chemotypes of other lichens". Carbohydrate Polymers. 40 (2): 101–106. doi:10.1016/S0144-8617(99)00048-X.

- Takeda, Tadahiro; Funatsu, Masami; Shibata, Shoji; Fukuoka, Fumiko (1972). "Polysaccharides of lichens and fungi. V. Antitumour active polysaccharides of lichens of Evernia, Acroscyphus and Alectoria spp". Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 20 (11): 2445–2449. doi:10.1248/cpb.20.2445. PMID 4650152.

- Fleming, M.; Manners, D.J. (1966). "The fine structure of isolichenin". Biochemical Journal. 100 (2): 24P. doi:10.1042/bj1000017P. PMC 1265181.

- Mccleary, Barry V.; Matheson, Norman K. (1987). "Enzymic analysis of polysaccharide structure". Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry Volume 44. Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry. 44. pp. 147–276 (see p. 265). doi:10.1016/S0065-2318(08)60079-7. ISBN 9780120072446. PMID 3101407.

- Yokota, Itsuro; Shibata, Shoji; Saitô, Hazime (1979). "A 13C-n.m.r. analysis of linkages in lichen polysaccharides: an approach to chemical taxonomy of lichens". Carbohydrate Research. 69 (1): 252–258. doi:10.1016/S0008-6215(00)85771-7.

- Gorin, Philip A.J.; Iacomini, Marcello (1984). "Polysaccharides of the lichens Cetraria islandica and Ramalina usnea". Carbohydrate Research. 128 (1): 119–132. doi:10.1016/0008-6215(84)85090-9.

- Thell, Arne; Crespo, Ana; Divakar, Pradeep K.; Kärnefelt, Ingvar; Leavitt, Steven D.; Lumbsch, H. Thorsten; Seaward, Mark R. D. (2012). "A review of the lichen family Parmeliaceae – history, phylogeny and current taxonomy". Nordic Journal of Botany. 30 (6): 641–664. doi:10.1111/j.1756-1051.2012.00008.x.

- Krämer, P; Wincierz, U; Grübler, G; Tschakert, J; Voelter, W; Mayer, H (1995). "Rational approach to fractionation, isolation, and characterization of polysaccharides from the lichen Cetraria islandica". Arzneimittel-forschung. 45 (6): 726–731. PMID 7646581.

- Smriga, Miro; Saito, Hiroshi (2000). "Effect of selected thallophytic glucans on learning behaviour and short-term potentiation". Phytotherapy Research. 14 (3): 153–155. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(200005)14:3<153::AID-PTR666>3.0.CO;2-J. PMID 10815005.

- Smriga, Miro; Chen, Ji; Zhang, Jun-Tian; Narui, Takao; Shibata, Shoji; Hirano, Eiko; Saito, Hiroshi (1999). "Isolichenan, an α-glucan isolated from the lichen Cetrariella islandica, repairs impaired learning behaviour and facilitates hippocampal synaptic plasticity". Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B. 75 (7): 219–223. doi:10.2183/pjab.75.219.

- Di Meo, Francesco; Donato, Stella; Di Pardo, Alba; Maglione, Vittorio; Filosa, Stefania; Crispi, Stefania (2018). "New therapeutic drugs from bioactive natural molecules: The role of gut microbiota metabolism in neurodegenerative diseases". Current Drug Metabolism. 19 (6): 478–489. doi:10.2174/1389200219666180404094147. PMID 29623833.

- Raval, Urdhva; Harary, Joyce M.; Zeng, Emma; Pasinetti, Giulio M. (2020). "The dichotomous role of the gut microbiome in exacerbating and ameliorating neurodegenerative disorders". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 20 (7): 673–686. doi:10.1080/14737175.2020.1775585. PMC 7387222. PMID 32459513.

- Cordeiro, Lucimara M.C.; Stocker-Wörgötter, Elfriede; Gorin, Philip A.J.; Iacomini, Marcello (2003). "Comparative studies of the polysaccharides from species of the genus Ramalina—lichenized fungi—of three distinct habitats". Phytochemistry. 63 (8): 967–975. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00336-4. PMID 12895548.

- Cordeiro, Lucimara M.C.; Iacomini, Marcello; Stocker-Wörgötter, Elfie (2004). "Culture studies and secondary compounds of six Ramalina species". Mycological Research. 108 (5): 489–497. doi:10.1017/S0953756204009402. PMID 15230001.

- Cordeiro, L.; Stockerworgotter, E.; Gorin, P.; Iacomini, M. (2004). "Elucidation of polysaccharide origin in symbiosis". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 238 (1): 79–84. doi:10.1016/j.femsle.2004.07.020. PMID 15336406.

- Honegger, Rosmarie; Haisch, Annette (2001). "Immunocytochemical location of the (1→3) (1→4)-beta-glucan lichenin in the lichen-forming ascomycete Cetraria islandica (Icelandic moss)". New Phytologist. 150 (3): 739–746. doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00122.x.

- Cordeiro, Lucimara M.C.; Messias, Douglas; Sassaki, Guilherme L.; Gorin, Phillip A.J.; Iacomini, Marcello (2011). "Does aposymbiotically cultivated fungus Ramalina produce isolichenan?". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 321 (1): 50–57. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02309.x. PMID 21585515.

- Freysdottir, J.; Omarsdottir, S.; Ingólfsdóttir, K.; Vikingsson, A.; Olafsdottir, E.S. (2008). "In vitro and in vivo immunomodulating effects of traditionally prepared extract and purified compounds from Cetraria islandica". International Immunopharmacology. 8 (3): 423–430. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2007.11.007. PMID 18279796.