Solubility

Solubility is the property of a solid, liquid or gaseous chemical substance called solute to dissolve in a solid, liquid or gaseous solvent. The solubility of a substance fundamentally depends on the physical and chemical properties of the solute and solvent as well as on temperature, pressure and presence of other chemicals (including changes to the pH) of the solution. The extent of the solubility of a substance in a specific solvent is measured as the saturation concentration, where adding more solute does not increase the concentration of the solution and begins to precipitate the excess amount of solute.

Insolubility is the inability to dissolve in a solid, liquid or gaseous solvent.

Most often, the solvent is a liquid, which can be a pure substance or a mixture. One may also speak of solid solution, but rarely of solution in a gas (see vapor–liquid equilibrium instead).

Under certain conditions, the equilibrium solubility can be exceeded to give a so-called supersaturated solution, which is metastable.[1] Metastability of crystals can also lead to apparent differences in the amount of a chemical that dissolves depending on its crystalline form or particle size. A supersaturated solution generally crystallises when 'seed' crystals are introduced and rapid equilibration occurs. Phenylsalicylate is one such simple observable substance when fully melted and then cooled below its fusion point.

Solubility is not to be confused with the ability to dissolve a substance, because the solution might also occur because of a chemical reaction. For example, zinc dissolves (with effervescence) in hydrochloric acid as a result of a chemical reaction releasing hydrogen gas in a displacement reaction. The zinc ions are soluble in the acid.

The solubility of a substance is an entirely different property from the rate of solution, which is how fast it dissolves. The smaller a particle is, the faster it dissolves although there are many factors to add to this generalization.

Crucially, solubility applies to all areas of chemistry, geochemistry, inorganic, physical, organic and biochemistry. In all cases it will depend on the physical conditions (temperature, pressure and concentration) and the enthalpy and entropy directly relating to the solvents and solutes concerned. By far the most common solvent in chemistry is water which is a solvent for most ionic compounds as well as a wide range of organic substances. This is a crucial factor in acidity and alkalinity and much environmental and geochemical work.

IUPAC definition

According to the IUPAC definition,[2] solubility is the analytical composition of a saturated solution expressed as a proportion of a designated solute in a designated solvent. Solubility may be stated in various units of concentration such as molarity, molality, mole fraction, mole ratio, mass (solute) per volume (solvent) and other units.

Qualifiers used to describe extent of solubility

The extent of solubility ranges widely, from infinitely soluble (without limit) (miscible[3]) such as ethanol in water, to poorly soluble, such as silver chloride in water. The term insoluble is often applied to poorly or very poorly soluble compounds. A number of other descriptive terms are also used to qualify the extent of solubility for a given application. For example, U.S. Pharmacopoeia gives the following terms:

| Term | Mass parts of solvent required to dissolve 1 mass part of solute[4] |

|---|---|

| Very soluble | <1 |

| Freely soluble | 1 to 10 |

| Soluble | 10 to 30 |

| Sparingly soluble | 30 to 100 |

| Slightly soluble | 100 to 1000 |

| Very slightly soluble | 1000 to 10,000 |

| Practically insoluble or insoluble | ≥ 10,000 |

The thresholds to describe something as insoluble, or similar terms, may depend on the application. For example, one source states that substances are described as "insoluble" when their solubility is less than 0.1 g per 100 mL of solvent.[5]

Molecular view

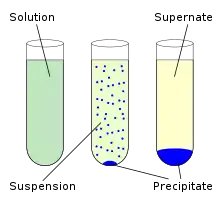

Solubility occurs under dynamic equilibrium, which means that solubility results from the simultaneous and opposing processes of dissolution and phase joining (e.g. precipitation of solids). The solubility equilibrium occurs when the two processes proceed at a constant rate.

The term solubility is also used in some fields where the solute is altered by solvolysis. For example, many metals and their oxides are said to be "soluble in hydrochloric acid", although in fact the aqueous acid irreversibly degrades the solid to give soluble products. It is also true that most ionic solids are dissolved by polar solvents, but such processes are reversible. In those cases where the solute is not recovered upon evaporation of the solvent, the process is referred to as solvolysis. The thermodynamic concept of solubility does not apply straightforwardly to solvolysis.

When a solute dissolves, it may form several species in the solution. For example, an aqueous suspension of ferrous hydroxide, Fe(OH)

2, will contain the series [Fe(H

2O)x(OH)x](2x)+ as well as other species. Furthermore, the solubility of ferrous hydroxide and the composition of its soluble components depend on pH. In general, solubility in the solvent phase can be given only for a specific solute that is thermodynamically stable, and the value of the solubility will include all the species in the solution (in the example above, all the iron-containing complexes).

Factors affecting solubility

Solubility is defined for specific phases. For example, the solubility of aragonite and calcite in water are expected to differ, even though they are both polymorphs of calcium carbonate and have the same chemical formula.

The solubility of one substance in another is determined by the balance of intermolecular forces between the solvent and solute, and the entropy change that accompanies the solvation. Factors such as temperature and pressure will alter this balance, thus changing the solubility.

Solubility may also strongly depend on the presence of other species dissolved in the solvent, for example, complex-forming anions (ligands) in liquids. Solubility will also depend on the excess or deficiency of a common ion in the solution, a phenomenon known as the common-ion effect. To a lesser extent, solubility will depend on the ionic strength of solutions. The last two effects can be quantified using the equation for solubility equilibrium.

For a solid that dissolves in a redox reaction, solubility is expected to depend on the potential (within the range of potentials under which the solid remains the thermodynamically stable phase). For example, solubility of gold in high-temperature water is observed to be almost an order of magnitude higher (i.e. about ten times higher) when the redox potential is controlled using a highly oxidizing Fe3O4-Fe2O3 redox buffer than with a moderately oxidizing Ni-NiO buffer.[6]

Solubility (metastable, at concentrations approaching saturation) also depends on the physical size of the crystal or droplet of solute (or, strictly speaking, on the specific surface area or molar surface area of the solute).[7] For quantification, see the equation in the article on solubility equilibrium. For highly defective crystals, solubility may increase with the increasing degree of disorder. Both of these effects occur because of the dependence of solubility constant on the Gibbs energy of the crystal. The last two effects, although often difficult to measure, are of practical importance. For example, they provide the driving force for precipitate aging (the crystal size spontaneously increasing with time).

Temperature

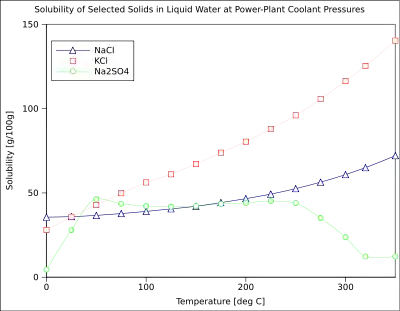

The solubility of a given solute in a given solvent is function of temperature. Depending on the change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of the dissolution reaction, i.e., on the endothermic (ΔG > 0) or exothermic (ΔG < 0) character of the dissolution reaction, the solubility of a given compound may increase or decrease with temperature. The van 't Hoff equation relates the change of solubility equilibrium constant (Ksp) to temperature change and to reaction enthalpy change (ΔH). For most solids and liquids, their solubility increases with temperature because their dissolution reaction is endothermic (ΔG > 0).[8] In liquid water at high temperatures, (e.g. that approaching the critical temperature), the solubility of ionic solutes tends to decrease due to the change of properties and structure of liquid water; the lower dielectric constant results in a less polar solvent and in a change of hydration energy affecting the ΔG of the dissolution reaction.

Gaseous solutes exhibit more complex behavior with temperature. As the temperature is raised, gases usually become less soluble in water (exothermic dissolution reaction related to their hydration) (to minimum, which is below 120 °C for most permanent gases[9]), but more soluble in organic solvents (endothermic dissolution reaction related to their solvatation).[8]

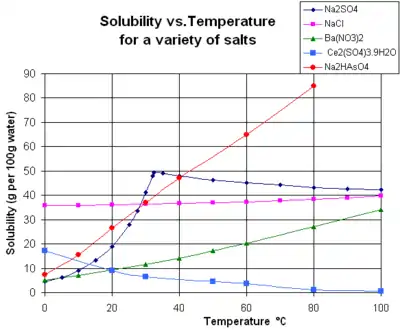

The chart shows solubility curves for some typical solid inorganic salts (temperature is in degrees Celsius i.e. kelvins minus 273.15).[10] Many salts behave like barium nitrate and disodium hydrogen arsenate, and show a large increase in solubility with temperature (ΔG > 0). Some solutes (e.g. sodium chloride in water) exhibit solubility that is fairly independent of temperature (ΔG ≈ 0). A few, such as calcium sulfate (gypsum) and cerium(III) sulfate, become less soluble in water as temperature increases (ΔG < 0).[11] This is also the case for calcium hydroxide (portlandite), whose solubility at 70 °C is about half of its value at 25 °C. The dissolution of calcium hydroxide in water is also an exothermic process (ΔG < 0) and obeys the van 't Hoff equation and Le Chatelier's principle. A lowering of temperature favors the removal of dissolution heat from the system and thus favors dissolution of Ca(OH)2: so portlandite solubility increases at low temperature. This temperature dependence is sometimes referred to as "retrograde" or "inverse" solubility. Occasionally, a more complex pattern is observed, as with sodium sulfate, where the less soluble decahydrate crystal (mirabilite) loses water of crystallization at 32 °C to form a more soluble anhydrous phase (thenardite) because the change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG), of the dissolution reaction.

The solubility of organic compounds nearly always increases with temperature. The technique of recrystallization, used for purification of solids, depends on a solute's different solubilities in hot and cold solvent. A few exceptions exist, such as certain cyclodextrins.[12]

Pressure

For condensed phases (solids and liquids), the pressure dependence of solubility is typically weak and usually neglected in practice. Assuming an ideal solution, the dependence can be quantified as:

where the index i iterates the components, Ni is the mole fraction of the ith component in the solution, P is the pressure, the index T refers to constant temperature, Vi,aq is the partial molar volume of the ith component in the solution, Vi,cr is the partial molar volume of the ith component in the dissolving solid, and R is the universal gas constant.[13]

The pressure dependence of solubility does occasionally have practical significance. For example, precipitation fouling of oil fields and wells by calcium sulfate (which decreases its solubility with decreasing pressure) can result in decreased productivity with time.

Solubility of gases

Henry's law is used to quantify the solubility of gases in solvents. The solubility of a gas in a solvent is directly proportional to the partial pressure of that gas above the solvent. This relationship is similar to the Raoult's law and can be written as:

where kH is a temperature-dependent constant (for example, 769.2 L·atm/mol for dioxygen (O2) in water at 298 K), p is the partial pressure (atm), and c is the concentration of the dissolved gas in the liquid (mol/L).

The solubility of gases is sometimes also quantified using Bunsen solubility coefficient.

In the presence of small bubbles, the solubility of the gas does not depend on the bubble radius in any other way than through the effect of the radius on pressure (i.e. the solubility of gas in the liquid in contact with small bubbles is increased due to pressure increase by Δp = 2γ/r; see Young–Laplace equation).[14]

Henry's law is valid for gases that do not undergo change of chemical speciation on dissolution. Sieverts' law shows a case when this assumption does not hold.

The carbon dioxide solubility in seawater is also affected by temperature, pH of the solution, and by the carbonate buffer. The decrease of solubility of carbon dioxide in seawater when temperature increases is also an important retroaction factor (positive feedback) exacerbating past and future climate changes as observed in ice cores from the Vostok site in Antarctica. At the geological time scale, because of the Milankovich cycles, when the astronomical parameters of the Earth orbit and its rotation axis progressively change and modify the solar irradiance at the Earth surface, temperature starts to increase. When a deglaciation period is initiated, the progressive warming of the oceans releases CO2 in the atmosphere because of its lower solubility in warmer sea water. On its turn, higher levels of CO2 in the atmosphere increase the greenhouse effect and carbon dioxide acts as an amplifier of the general warming.

Polarity

A popular aphorism used for predicting solubility is "like dissolves like" also expressed in the Latin language as "Similia similibus solventur".[15] This statement indicates that a solute will dissolve best in a solvent that has a similar chemical structure to itself. This view is simplistic, but it is a useful rule of thumb. The overall solvation capacity of a solvent depends primarily on its polarity.[lower-alpha 1] For example, a very polar (hydrophilic) solute such as urea is very soluble in highly polar water, less soluble in fairly polar methanol, and practically insoluble in non-polar solvents such as benzene. In contrast, a non-polar or lipophilic solute such as naphthalene is insoluble in water, fairly soluble in methanol, and highly soluble in non-polar benzene.[16]

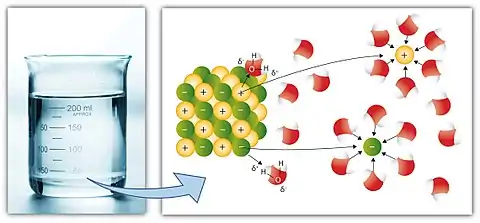

In even more simple terms a simple ionic compound (with positive and negative ions) such as sodium chloride (common salt) is easily soluble in a highly polar solvent (with some separation of positive (δ+) and negative (δ-) charges in the covalent molecule) such as water, as thus the sea is salty as it accumulates dissolved salts since early geological ages.

The solubility is favored by entropy of mixing (ΔS) and depends on enthalpy of dissolution (ΔH) and the hydrophobic effect. The free energy of dissolution (Gibbs energy) depends on temperature and is given by the relationship: ΔG = ΔH – TΔS.

Chemists often exploit differences in solubilities to separate and purify compounds from reaction mixtures, using the technique of liquid-liquid extraction. This applies in vast areas of chemistry from drug synthesis to spent nuclear fuel reprocessing.

Rate of dissolution

Dissolution is not an instantaneous process. The rate of solubilization (in kg/s) is related to the solubility product and the surface area of the material. The speed at which a solid dissolves may depend on its crystallinity or lack thereof in the case of amorphous solids and the surface area (crystallite size) and the presence of polymorphism. Many practical systems illustrate this effect, for example in designing methods for controlled drug delivery. In some cases, solubility equilibria can take a long time to establish (hours, days, months, or many years; depending on the nature of the solute and other factors).

The rate of dissolution can be often expressed by the Noyes–Whitney equation or the Nernst and Brunner equation[17] of the form:

where:

- m = mass of dissolved material

- t = time

- A = surface area of the interface between the dissolving substance and the solvent

- D = diffusion coefficient

- d = thickness of the boundary layer of the solvent at the surface of the dissolving substance

- Cs = mass concentration of the substance on the surface

- Cb = mass concentration of the substance in the bulk of the solvent

For dissolution limited by diffusion (or mass transfer if mixing is present), Cs is equal to the solubility of the substance. When the dissolution rate of a pure substance is normalized to the surface area of the solid (which usually changes with time during the dissolution process), then it is expressed in kg/m2s and referred to as "intrinsic dissolution rate". The intrinsic dissolution rate is defined by the United States Pharmacopeia.

Dissolution rates vary by orders of magnitude between different systems. Typically, very low dissolution rates parallel low solubilities, and substances with high solubilities exhibit high dissolution rates, as suggested by the Noyes-Whitney equation.

Quantification of solubility

Solubility is commonly expressed as a concentration; for example, as g of solute per kg of solvent, g per dL (100mL) of solvent, molarity, molality, mole fraction, etc. The maximum equilibrium amount of solute that can dissolve per amount of solvent is the solubility of that solute in that solvent under the specified conditions. The advantage of expressing solubility in this manner is its simplicity, while the disadvantage is that it can strongly depend on the presence of other species in the solvent (for example, the common ion effect).

Solubility constants are used to describe saturated solutions of ionic compounds of relatively low solubility (see solubility equilibrium). The solubility constant is a special case of an equilibrium constant. It describes the balance between dissolved ions from the salt and undissolved salt. The solubility constant is also "applicable" (i.e. useful) to precipitation, the reverse of the dissolving reaction. As with other equilibrium constants, temperature can affect the numerical value of solubility constant. The solubility constant is not as simple as solubility, however the value of this constant is generally independent of the presence of other species in the solvent.

The Flory–Huggins solution theory is a theoretical model describing the solubility of polymers. The Hansen solubility parameters and the Hildebrand solubility parameters are empirical methods for the prediction of solubility. It is also possible to predict solubility from other physical constants such as the enthalpy of fusion.

The octanol-water partition coefficient, usually expressed as its logarithm (Log P) is a measure of differential solubility of a compound in a hydrophobic solvent (1-octanol) and a hydrophilic solvent (water). The logarithm of these two values enables compounds to be ranked in terms of hydrophilicity (or hydrophobicity).

The energy change associated with dissolving is usually given per mole of solute as the enthalpy of solution.

Applications

Solubility is of fundamental importance in a large number of scientific disciplines and practical applications, ranging from ore processing and nuclear reprocessing to the use of medicines, and the transport of pollutants.

Solubility is often said to be one of the "characteristic properties of a substance", which means that solubility is commonly used to describe the substance, to indicate a substance's polarity, to help to distinguish it from other substances, and as a guide to applications of the substance. For example, indigo is described as "insoluble in water, alcohol, or ether but soluble in chloroform, nitrobenzene, or concentrated sulfuric acid".

Solubility of a substance is useful when separating mixtures. For example, a mixture of salt (sodium chloride) and silica may be separated by dissolving the salt in water, and filtering off the undissolved silica. The synthesis of chemical compounds, by the milligram in a laboratory, or by the ton in industry, both make use of the relative solubilities of the desired product, as well as unreacted starting materials, byproducts, and side products to achieve separation.

Another example of this is the synthesis of benzoic acid from phenylmagnesium bromide and dry ice. Benzoic acid is more soluble in an organic solvent such as dichloromethane or diethyl ether, and when shaken with this organic solvent in a separatory funnel, will preferentially dissolve in the organic layer. The other reaction products, including the magnesium bromide, will remain in the aqueous layer, clearly showing that separation based on solubility is achieved. This process, known as liquid–liquid extraction, is an important technique in synthetic chemistry. Recycling is used to ensure maximum extraction.

Differential solubility

In flowing systems, differences in solubility often determine the dissolution-precipitation driven transport of species. This happens when different parts of the system experience different conditions. Even slightly different conditions can result in significant effects, given sufficient time.

For example, relatively low solubility compounds are found to be soluble in more extreme environments, resulting in geochemical and geological effects of the activity of hydrothermal fluids in the Earth's crust. These are often the source of high quality economic mineral deposits and precious or semi-precious gems. In the same way, compounds with low solubility will dissolve over extended time (geological time), resulting in significant effects such as extensive cave systems or Karstic land surfaces.

Solubility of ionic compounds in water

Some ionic compounds (salts) dissolve in water, which arises because of the attraction between positive and negative charges (see: solvation). For example, the salt's positive ions (e.g. Ag+) attract the partially negative oxygens in H2O. Likewise, the salt's negative ions (e.g. Cl−) attract the partially positive hydrogens in H2O. Note: oxygen is partially negative because it is more electronegative than hydrogen, and vice versa (see: chemical polarity).

- AgCl(s) ⇌ Ag+(aq) + Cl−(aq)

However, there is a limit to how much salt can be dissolved in a given volume of water. This amount is given by the solubility product, Ksp. This value depends on the type of salt (AgCl vs. NaCl, for example), temperature, and the common ion effect.

One can calculate the amount of AgCl that will dissolve in 1 liter of water, some algebra is required.

- Ksp = [Ag+] × [Cl−] (definition of solubility product)

- Ksp = 1.8 × 10−10 (from a table of solubility products)

[Ag+] = [Cl−], in the absence of other silver or chloride salts,

- [Ag+]2 = 1.8 × 10−10

- [Ag+] = 1.34 × 10−5

The result: 1 liter of water can dissolve 1.34 × 10−5 moles of AgCl(s) at room temperature. Compared with other types of salts, AgCl is poorly soluble in water. In contrast, table salt (NaCl) has a higher Ksp and is, therefore, more soluble.

| Soluble | Insoluble[18] |

|---|---|

| Group I and NH4+ compounds (except lithium phosphate) | Carbonates (Except Group I, NH4+ and uranyl compounds) |

| Nitrates | Sulfites (Except Group I and NH4+ compounds) |

| Acetates (ethanoates) (Except Ag+ compounds) | Phosphates (Except Group I and NH4+ compounds (excluding Li+)) |

| Chlorides (chlorates and perchlorates), bromides and iodides (Except Ag+, Pb2+, Cu+ and Hg22+) | Hydroxides and oxides (Except Group I, NH4+, Ba2+, Sr2+ and Tl+) |

| Sulfates (Except Ag+, Pb2+, Ba2+, Sr2+ and Ca2+) | Sulfides (Except Group I, Group II and NH4+ compounds) |

Solubility of organic compounds

The principle outlined above under polarity, that like dissolves like, is the usual guide to solubility with organic systems. For example, petroleum jelly will dissolve in gasoline because both petroleum jelly and gasoline are non-polar hydrocarbons. It will not, on the other hand, dissolve in ethyl alcohol or water, since the polarity of these solvents is too high. Sugar will not dissolve in gasoline, since sugar is too polar in comparison with gasoline. A mixture of gasoline and sugar can therefore be separated by filtration or extraction with water.

Solid solution

This term is often used in the field of metallurgy to refer to the extent that an alloying element will dissolve into the base metal without forming a separate phase. The solvus or solubility line (or curve) is the line (or lines) on a phase diagram that give the limits of solute addition. That is, the lines show the maximum amount of a component that can be added to another component and still be in solid solution. In the solid's crystalline structure, the 'solute' element can either take the place of the matrix within the lattice (a substitutional position; for example, chromium in iron) or take a place in a space between the lattice points (an interstitial position; for example, carbon in iron).

In microelectronic fabrication, solid solubility refers to the maximum concentration of impurities one can place into the substrate.

Incongruent dissolution

Many substances dissolve congruently (i.e. the composition of the solid and the dissolved solute stoichiometrically match). However, some substances may dissolve incongruently, whereby the composition of the solute in solution does not match that of the solid. This solubilization is accompanied by alteration of the "primary solid" and possibly formation of a secondary solid phase. However, in general, some primary solid also remains and a complex solubility equilibrium establishes. For example, dissolution of albite may result in formation of gibbsite.[19]

- NaAlSi3O8(s) + H+ + 7H2O ⇌ Na+ + Al(OH)3(s) + 3H4SiO4.

In this case, the solubility of albite is expected to depend on the solid-to-solvent ratio. This kind of solubility is of great importance in geology, where it results in formation of metamorphic rocks.

Solubility prediction

Solubility is a property of interest in many aspects of science, including but not limited to: environmental predictions, biochemistry, pharmacy, drug-design, agrochemical design, and protein ligand binding. Aqueous solubility is of fundamental interest owing to the vital biological and transportation functions played by water.[20][21][22] In addition, to this clear scientific interest in water solubility and solvent effects; accurate predictions of solubility are important industrially. The ability to accurately predict a molecule's solubility represents potentially large financial savings in many chemical product development processes, such as pharmaceuticals.[23] In the pharmaceutical industry, solubility predictions form part of the early stage lead optimisation process of drug candidates. Solubility remains a concern all the way to formulation.[23] A number of methods have been applied to such predictions including quantitative structure–activity relationships (QSAR), quantitative structure–property relationships (QSPR) and data mining. These models provide efficient predictions of solubility and represent the current standard. The draw back such models is that they can lack physical insight. A method founded in physical theory, capable of achieving similar levels of accuracy at an sensible cost, would be a powerful tool scientifically and industrially.[24][25][26][27]

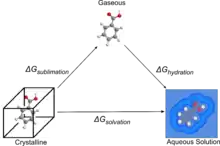

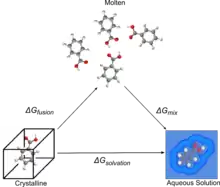

Methods founded in physical theory tend to use thermodynamic cycles, a concept from classical thermodynamics. The two common thermodynamic cycles used involve either the calculation of the free energy of sublimation (solid to gas without going through a liquid state) and the free energy of solvating a gaseous molecule (gas to solution), or the free energy of fusion (solid to a molten phase) and the free energy of mixing (molten to solution). These two process are represented in the following diagrams.

These cycles have been used for attempts at first principles predictions (solving using the fundamental physical equations) using physically motivated solvent models,[25] to create parametric equations and QSPR models[28][26] and combinations of the two.[26] The use of these cycles enables the calculation of the solvation free energy indirectly via either gas (in the sublimation cycle) or a melt (fusion cycle). This is helpful as calculating the free energy of solvation directly is extremely difficult. The free energy of solvation can be converted to a solubility value using various formulae, the most general case being shown below, where the numerator is the free energy of solvation, R is the gas constant and T is the temperature in kelvins.[25]

Well known fitted equations for solubility prediction are the general solubility equations. These equations stem from the work of Yalkowsky et al.[29][30] The original formula is given first followed by a revised formula which takes a different assumption of complete miscibility in octanol.[30] These equations are founded on the principles of the fusion cycle.

See also

- Apparent molar property

- Biopharmaceutics Classification System

- Dühring's rule

- Fajans–Paneth–Hahn Law

- Flexible SPC water model

- Henry's law – Relation of equilibrium solubility of a gas in a liquid to its partial pressure in the contacting gas phase

- Hot water extraction

- Hydrotrope

- Micellar solubilization

- Raoult's law – A law of thermodynamics for vapour pressure of a mixture

- Rate of solution

- Solubility equilibrium

- van 't Hoff equation – Relation between temperature and the equilibrium constant of a chemical reaction

Notes

- The solvent polarity is defined as its solvation power according to Reichardt.

References

- "Cancerweb.ncl.ac.uk". Online Medical Dictionary. Newcastle University. Archived from the original on January 25, 2009.

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Solubility". doi:10.1351/goldbook.S05740

- Clugston, M.; Fleming, R. (2000). Advanced Chemistry (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford Publishing. p. 108.

- "Pharmacopeia of the United States of America, 32nd revision, and the National Formulary, 27th edition," 2009, pp.1 to 12.

- Rogers, Elizabeth; Stovall, Iris (2000). "Fundamentals of Chemistry: Solubility". Department of Chemistry. University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- I.Y. Nekrasov (1996). Geochemistry, Mineralogy and Genesis of Gold Deposits. Taylor & Francis. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-90-5410-723-1.

- Hefter, G.T.; Tomkins, R.P.T (Editors) (2003). The Experimental Determination of Solubilities. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-471-49708-0.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- John W. Hill, Ralph H. Petrucci, General Chemistry, 2nd edition, Prentice Hall, 1999.

- P. Cohen, ed. (1989). The ASME Handbook on Water Technology for Thermal Power Systems. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers. p. 442.

- Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (27th ed.). Cleveland, Ohio: Chemical Rubber Publishing Co. 1943.

- "What substances, such as cerium sulfate, have a lower solubility when they are heated?". Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- Salvatore Filippone, Frank Heimanna and André Rassat (2002). "A highly water-soluble 2+1 b-cyclodextrin–fullerene conjugate". Chem. Commun. 2002 (14): 1508–1509. doi:10.1039/b202410a.

- E.M. Gutman (1994). Mechanochemistry of Solid Surfaces. World Scientific Publishing Co.

- G.W. Greenwood (1969). "The Solubility of Gas Bubbles". Journal of Materials Science. 4 (4): 320–322. Bibcode:1969JMatS...4..320G. doi:10.1007/BF00550401.

- Kenneth J. Williamson (1994). Macroscale and Microscale Organic Experiments (2nd ed.). Lexington, Massachusetts: D. C, Heath. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-669-19429-6.

- Merck Index (7th ed.). Merck & Co. 1960.

- Dokoumetzidis, Aristides; Macheras, Panos (2006). "A century of dissolution research: From Noyes and Whitney to the Biopharmaceutics Classification System". Int. J. Pharm. 321 (1–2): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.07.011. PMID 16920290.

- C. Houk; R. Post, eds. (1997). Chemistry, Concept and Problems. John Wiley & Sons. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-471-12120-6.

- O.M. Saether; P. de Caritat, eds. (1997). Geochemical processes, weathering and groundwater recharge in catchments. Rotterdam: Taylor & Francis. p. 6. ISBN 978-90-5410-641-8.

- Skyner, R.; McDonagh, J. L.; Groom, C. R.; van Mourik, T.; Mitchell, J. B. O. (2015). "A Review of Methods for the Calculation of Solution Free Energies and the Modelling of Systems in Solution" (PDF). Phys Chem Chem Phys. 17 (9): 6174–91. Bibcode:2015PCCP...17.6174S. doi:10.1039/C5CP00288E. PMID 25660403.

- Tomasi, J.; Mennucci, B.; Cammi, R. (2005). "Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models". Chemical Reviews. 105 (8): 2999–3093. doi:10.1021/cr9904009. PMID 16092826.

- Cramer, C. J.; Truhlar, D. G. (1999). "Implicit Solvation Models: Equilibria, Structure, Spectra, and Dynamics". Chemical Reviews. 99 (8): 2161–2200. doi:10.1021/cr960149m. PMID 11849023.

- Abramov, Y. A. (2015). "Major Source of Error in QSPR Prediction of Intrinsic Thermodynamic Solubility of Drugs: Solid vs Nonsolid State Contributions?". Molecular Pharmaceutics. 12 (6): 2126–2141. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00119. PMID 25880026.

- McDonagh, J. L. (2015). Computing the Aqueous solubility of Organic Drug-Like Molecules and Understanding Hydrophobicity. University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/6534.

- Palmer, D. S.; McDonagh, J. L.; Mitchell, J. B. O.; van Mourik, T.; Fedorov, M. V. (2012). "First-Principles Calculation of the Intrinsic Aqueous Solubility of Crystalline Druglike Molecules". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 8 (9): 3322–3337. doi:10.1021/ct300345m. PMID 26605739.

- McDonagh, J. L.; Nath, N.; De Ferrari, L.; van Mourik, T.; Mitchell, J. B. O. (2014). "Uniting Cheminformatics and Chemical Theory To Predict the Intrinsic Aqueous Solubility of Crystalline Druglike Molecules". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 54 (3): 844–856. doi:10.1021/ci4005805. PMC 3965570. PMID 24564264.

- Lusci, A.; Pollastri, G.; Baldi, P. (2013). "Deep Architectures and Deep Learning in Chemoinformatics: The Prediction of Aqueous Solubility for Drug-Like Molecules". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 53 (7): 1563–1575. doi:10.1021/ci400187y. PMC 3739985. PMID 23795551.

- Ran, Y.; N. Jain; S.H. Yalkowsky (2001). "Prediction of Aqueous Solubility of Organic Compounds by the General Solubility Equation (GSE)". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 41 (5): 1208–1217. doi:10.1021/ci010287z.

- Yalkowsky, S.H.; Valvani, S.C. (1980). "Solubility and partitioning I: solubility of nonelectrolytes in water". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 69 (8): 912–922. doi:10.1002/jps.2600690814. PMID 7400936.

- Jain, N.; Yalkowsky, S.H. (2001). "Estimation of the aqueous solubility I: application to organic nonelectrolytes". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 90 (2): 234–252. doi:10.1002/1520-6017(200102)90:2<234::aid-jps14>3.0.co;2-v.

External links

| Look up soluble or solubility in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |