Japanese clothing

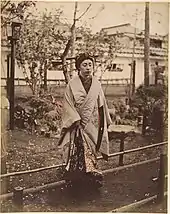

There are typically two types of clothing worn in Japan: traditional clothing known as Japanese clothing (和服, wafuku), including the national dress of Japan, the kimono, and Western clothing (洋服, yōfuku), which encompasses all else not recognised as either national dress or the dress of another country.

Traditional Japanese fashion represents a long-standing history of traditional culture, encompassing colour palettes developed in the Heian period, silhouettes adopted from Tang dynasty clothing and cultural traditions, motifs taken from Japanese culture, nature and traditional literature, and styles of wearing primarily fully-developed by the end of the Edo period. The most well-known form of traditional Japanese fashion is the kimono, translating literally as "something to wear" or "thing worn on the shoulders".[1] Other types of traditional fashion include the clothing of the Ainu people (known as the attus)[2] and the clothes of the Ryukyuan people (known as ryusou),[3][4] most notably including the traditional fabrics of bingata and bashōfu[2] produced on the Ryukyu Islands.

Modern Japanese fashion mostly encompasses yōfuku (Western clothes), though many well-known Japanese fashion designers - such as Issey Miyake, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo - have taken inspiration from and at times designed clothes taking influence from traditional fashion. Their works represent a combined impact on the global fashion industry, with many pieces displayed at fashion shows all over the world,[5] as well as having had an impact within the Japanese fashion industry itself, with many designers either drawing from or contributing to Japanese street fashion.

Despite previous generations wearing traditional clothing near-entirely, following the end of World War II, Western clothing and fashion became increasingly popular due to their increasingly-available nature and, over time, their cheaper price.[6] It is now increasingly rare for someone to wear traditional clothing as everyday clothes, and over time, traditional clothes within Japan have garnered an association with being difficult to wear and expensive. As such, traditional garments are now mainly worn for ceremonies and special events, with the most common time for someone to wear traditional clothes being to summer festivals, when the yukata is most appropriate; outside of this, the main groups of people most likely to wear traditional clothes are geisha, maiko and sumo wrestlers, all of whom are required to wear traditional clothing in their profession.

Traditional Japanese clothing has, over time, garnered fascination in the Western world as a representation of a different culture; first gaining popularity in the 1860s, Japonisme saw traditional clothing - some produced exclusively for export and differing in construction from the clothes worn by Japanese people everyday - exported to the West, where it soon became a popular item of clothing for artists and fashion designers. Fascination for the clothing of Japanese people continued into WW2, where some stereotypes of Japanese culture such as "geisha girls" became widespread. Over time, depictions and interest in traditional and modern Japanese clothing has generated discussions surrounding cultural appropriation and the ways in which clothing can be used to stereotype a culture; in 2016, the "Kimono Wednesday" event held at the Boston Museum of Arts became a key example of this.[7]

History

Nara period (710-794)

Social segregation of clothing was primarily noticeable in the Nara period (710-794), through the division of upper and lower class. Women of higher social status wore clothing that covered the majority of their body, or as Svitlana Rybalko states, "the higher the status, the less was open to other people's eyes". For example, the full-length robes would cover most from the collarbone to the feet, the sleeves were to be long enough to hide their fingertips, and fans were carried to protect them from speculative looks.[6]

Heian period (794-1185)

When the Heian period began (794-1185), the concept of the hidden body remained, with ideologies suggesting that the clothes served as "protection from the evil spirits and outward manifestation of a social rank". This proposed the widely held belief that those of lower ranking, who were perceived to be of less clothing due to their casual performance of manual labor, were not protected in the way that the upper class were in that time period. This was also the period in which Japanese traditional clothing became introduced to the Western world.[6]

1185 - Present

As time passed, new approaches to the costume were brought up, but the original mindset of a covered body lingered. The new trend of tattoos competed with the social concept of hidden skin and led to differences in opinion among the Japanese community and their social values. The dress code that was once followed on a daily basis reconstructed into a festive and occasional trend.[6]

Western influence

_-_panoramio_(1).jpg.webp)

In Japan, modern Japanese fashion history might be conceived as a gradual westernization of Japanese clothes; both the woolen and worsted industries in Japan originated as a product of Japan's re-established contact with the West in the early Meiji period (1850s-1860s). Before the 1860s, Japanese clothing consisted entirely of kimono of a number of varieties. These first appeared in the Jōmon period (14,500 B.C. – 300 B.C.), with no distinction between male and female.

With the opening of Japan's ports for international trade in the 1860s, clothing from a number of different cultures arrived as exports; despite Japan's historic contact with the Dutch before this time through its southerly ports, Western clothing had not caught on, despite the study of and fascination with Dutch technologies and writings.

The first Japanese to adopt Western clothing were officers and men of some units of the shōgun's army and navy; sometime in the 1850s, these men adopted woolen uniforms worn by the English marines stationed at Yokohama. Wool was difficult to produce domestically, with the cloth having to be imported. Outside of the military, other early adoptions of Western dress were mostly within the public sector, and typically entirely male, with women continuing to wear kimono both inside and outside of the home, and men changing into the kimono usually within the home for comfort.[8]

From this point on, Western clothing styles spread outwards of the military and upper public sectors, with courtiers and bureaucrats urged to adopt Western clothing, promoted as both modern and more practical. The Ministry of Education ordered that Western-style student uniforms be worn in public colleges and universities. Businessmen, teachers, doctors, bankers, and other leaders of the new society wore suits to work and at large social functions. Despite Western clothing becoming popular within the workplace, in schools and on the streets, it was not worn by everybody, and was actively considered uncomfortable and undesirable by some; one account tells of a father promising to buy his daughters new kimono as a reward for wearing Western clothing and eating meat.[9] A number of different fashions from the West arrived and were also incorporated into the way that people wore kimono; numerous woodblock prints from the later Meiji period show men wearing bowler hats and carrying Western-style umbrellas whilst wearing kimono, and Gibson girl hairstyles - typically a large bun on top of a relatively wide hairstyle, similar to the Japanese nihongami - became popular amongst Japanese women as a more low-effort hairstyle for everyday life.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Western dress had become a symbol of social dignity and progressiveness; however, the kimono was still considered to be fashion, with the two styles of dress essentially growing in parallel with one another over time. With Western dress being considered street wear and a more formal display of fashionable clothing, most Japanese people wore the comfortable kimono at home and when out of the public eye.[8]

Until the 1930s, the majority of Japanese wore the kimono, and Western clothes were still restricted to out-of-home use by certain classes. The Japanese have interpreted western clothing styles from the United States and Europe and made it their own. Overall, it is evident throughout history that there has been much more of a Western influence on Japan's culture and clothing. However, the traditional kimono remains a major part of the Japanese way of life and will be for a long time.[8]

Types of traditional clothing

Kimono

The kimono (着物), labelled the "national costume of Japan",[1] is the most well-known form of traditional Japanese clothing. The kimono is worn wrapped around the body, left side over right, and is sometimes worn layered. It is always worn with an obi, and may be worn with a number of traditional accessories and types of footwear.[10] Kimono differ in construction and wear between men and women.

After the four-class system ended in the Tokugawa period (1603-1867), the symbolic meaning of the kimono shifted from a reflection of social class to a reflection of self, allowing people to incorporate their own tastes and individualize their outfit. The process of wearing a kimono requires, depending on gender and occasion, a sometimes detailed knowledge of a number of different steps and methods of tying the obi, with formal kimono for women requiring at times the help of someone else to put on. Post-WW2, kimono schools were built to teach those interested in kimono how to wear it and tie a number of different knots.[1]

A number of different types of kimono exist that are worn in the modern day, with women having more varieties than men. Whereas men's kimono differ in formality typically through fabric choice, the number of crests on the garment (known as mon or kamon) and the accessories worn with it, women's kimono differ in formality through fabric choice, decoration style, construction and crests.

Women's kimono

- The furisode (lit., "swinging sleeve") is a type of formal kimono usually worn by young women, often for Coming of Age Day or as bridalwear, and is considered the most formal kimono for young women.

- The uchikake is also worn as bridalwear as an unbelted outer layer.

- The kurotomesode and irotomesode are formal kimono with a design solely along the hem, and are considered the most formal kimono for women outside of the furisode.

- The houmongi and the tsukesage are semi-formal women's kimono featuring a design on part of the sleeves and hem.

- The iromuji is a low-formality solid-colour kimono worn for tea ceremony and other mildly-formal events.

- The komon and edo komon are informal kimono with a repeating pattern all over the kimono.

Other types of kimono, such as the yukata and mofuku (mourning) kimono are worn by both men and women, with differences only in construction and sometimes decoration. In previous decades, women only stopped wearing the furisode when they got married, typically in their early- to mid-twenties; however, in the modern day, a woman will usually stop wearing furisode around this time whether she is married or not.[10]

Dressing in kimono

The word kimono literally translates as "thing to wear", and up until the 19th century it was the main form of dress worn by men and women alike in Japan.[11]

Traditionally, the art of wearing kimono (known as kitsuke) was passed from mother to daughter as simply learning how to dress, and in the modern day, this is also taught in specialist kimono schools.[10] First, one puts on tabi, which are white cotton socks.[11] Then the undergarments are put on followed by a top and a wraparound skirt.[11] Next, the nagajuban (under-kimono) is put on, which is then tied by a koshihimo.[11] Finally, the kimono is put on, with the left side covering the right, tied in place with one or two koshihimo and smoothed over with a datejime belt. The obi is then tied in place. Kimono are always worn left-over-right unless being worn by the dead, in which case they are worn right-over-left.[11] When the kimono is worn outside, either zōri or geta sandals are traditionally worn.[11]

Women typically wear kimono when they attend traditional arts, such as a tea ceremonies or ikebana classes.[8] During wedding ceremonies, the bride and groom will often go through many costume changes; though the bride may start off in an entirely-white outfit before switching to a colourful one,[10] grooms will wear black kimono made from habutae silk.

Funeral kimono (mofuku) for both men and women are plain black with five crests, though Western clothing is also worn to funerals. Any plain black kimono with less than five crests is not considered to be mourning wear.

The "coming of age" ceremony, Seijin no Hi, is another occasion where kimono are worn.[12] At these annual celebrations, women wear brightly-coloured furisode, often with fur stoles around the neck. Other occasions where kimono are traditionally worn in the modern day include the period surrounding the New Year, graduation ceremonies, and Shichi-go-san, which is a celebration for children aged 3, 5 and 7.

Seasons

Kimono are matched with seasons. Awase (lined) kimono, made of silk, wool, or synthetic fabrics, are worn during the cooler months.[8] During these months, kimono with more rustic colours and patterns (like russet leaves), and kimono with darker colours and multiple layers, are favoured.[8] Lightweight cotton yukata are worn by men and women during the spring and summer months. In the warmer weather months, vibrant colors and floral designs (like cherry blossoms) are common.[8]

Materials

Up until the fifteenth century the vast majority of kimono worn by most people were made of hemp or linen, and they were made with multiple layers of materials.[13] Today, kimono can be made of silk, silk brocade, silk crepes (such as chirimen) and satin weaves (such as rinzu).[13] Modern kimono that are made with less-expensive easy-care fabrics such as rayon, cotton sateen, cotton, polyester and other synthetic fibers, are more widely worn today in Japan.[13] However, silk is still considered the ideal fabric for more formal kimono.[8]

Kimono are typically 39-43 inches long with eight 14-15 inch-wide pieces.[14] These pieces are sewn together to create the basic T-shape. Kimono are traditionally sewn by hand, a technique known as wasai.[14] However, even machine-made kimono require substantial hand-stitching.

Kimono are traditionally made from a single bolt of fabric called a tanmono.[8] Tanmono come in standard dimensions, and the entire bolt is used to make one kimono.[8] The finished kimono consists of four main strips of fabric — two panels covering the body and two panels forming the sleeves — with additional smaller strips forming the narrow front panels and collar.[14] Kimono fabrics are frequently hand-made and -decorated.

Kimono are worn with sash-belts called obi, of which there are several varieties. In previous centuries, obi were relatively pliant and soft, so literally held the kimono closed; modern-day obi are generally stiffer, meaning the kimono is actually kept closed through tying a series of flat ribbons, such as kumihimo, around the body. The two most common varieties of obi for women are fukuro obi, which can be worn with everything but the most casual forms of kimono, and nagoya obi, which are narrower at one end to make them easier to wear.

Yukata

The yukata (浴衣) is an informal kimono worn specifically in the spring and summer, and it is generally less expensive than the traditional kimono. Because it was made for warm weather, yukata are almost entirely made of cotton of an often lighter weight and brighter color than most kimono fabrics. It is worn for festivals and cherry blossom viewing ceremonies.[15]

Hakama, obi, zōri

The hakama, which resembles a long, wide pleated skirt, is generally worn over the kimono and is considered formal wear. Although it was traditionally created to be worn by men of all occupations (craftsmen, farmers, samurai, etc.), it is now socially accepted to be worn by women as well.

The obi is similar to a belt, wrapping around the outer kimono and helping to keep all of the layers together, though it does not actually tie them closed. Obi are typically long, rectangular belts that can be decorated and coloured in a variety of different ways, as well as being made of a number of different fabrics. Modern obi are typically made of a crisp, if not stiff, weave of fabric, and may be relatively thick and unpliant.

Zōri are a type of sandal worn with kimono that resemble flip-flops by design, with the exception that the base is sturdier and at times forms a gently sloping heel. Zōri can be made of wood, leather and vinyl, with more formal varieties featuring decorated straps (known as hanao) that may be embroidered and woven with gold and silver yarn. These shoes are typically worn with white socks usually mostly covered by the kimono's hem. Geta are sandals similar to zōri that are made to be worn in the snow or dirt, featured with wooden columns underneath the shoes.[15]

Design

Designers

Multiple designers use the kimono as a foundation for their current designs, being influenced by its cultural and aesthetic aspects and including them into their garments.

Issey Miyake is most known for crossing boundaries in fashion and reinventing forms of clothing while simultaneously transmitting the traditional qualities of the culture into his work. He has explored various techniques in design, provoking discussion on what identifies as "dress". He has also been tagged the "Picasso of Fashion" due to his recurring confrontation of traditional values. Miyake found interest in working with dancers to create clothing that would best suit them and their aerobic movements, eventually replacing the models he initially worked with for dancers, in hopes of producing clothing that benefits people of all classifications.[5] His use of pleats and polyester jersey reflected a modern form of fashion due to their practical comfort and elasticity. Over 10 years of Miyake's work was featured in Paris in 1998 at the "Issey Miyake: Making Things" exhibition. His two most popular series were titled, "Pleats, Please" and "A-POC (A piece of Cloth)".

Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo are Japanese fashion designers who share similar tastes in design and style, their work often considered by the public to be difficult to differentiate. They were influenced by social conflicts, as their recognizable work bloomed and was influenced by the post war era of Japan. They differ from Miyake and several other fashion designers in their dominating use of dark colors, especially the color black. Traditional clothing often included a variety of colors in their time, and their use of "the absence of color" provoked multiple critics to voice their opinions and criticize the authenticity of their work. American Vogue of April 1983 labeled the two "avant-garde designers", eventually leading them to their success and popularity.[5]

Aesthetics

The Japanese are often recognized for their traditional art and its capability of transforming simplicity into creative designs. As stated by Valerie Foley, "Fan shapes turn out to be waves, waves metamorphose into mountains; simple knots are bird wings; wobbly semicircles signify half-submerged Heian period carriage wheels".[16] These art forms have been transferred onto fabric that then mold into clothing. With traditional clothing, specific techniques are used and followed, such as metal applique, silk embroidery, and paste- resist. The type of fabric used to produce the clothing was often indicative of a person's social class, for the wealthy were able to afford clothing created with fabrics of higher quality. Stitching techniques and the fusion of colors also distinguished the wealthy from the commoner, as those of higher power had a tendency to wear ornate, brighter clothing.[17]

Influence on modern fashion

Tokyo street fashion

.jpg.webp)

Japanese street fashion emerged in the 1990s and differed from traditional fashion in the sense that it was initiated and popularized by the general public, specifically teenagers, rather than by fashion designers.[18] Different forms of street fashion have emerged in different Tokyo locales, such as the lolita in Harajuku the ageha of Shibuya.

Lolita fashion became popular in the mid 2000s. It is characterized by "a knee length skirt or dress in a bell shape assisted by petticoats, worn with a blouse, knee high socks or stockings and a headdress".[18] Different sub-styles of lolita include casual, gothic, and hime. Ageha (揚羽, swallowtail butterfly) is based on a Shibuya club-hostess look, with dark, heavy eyeliner, false eyelashes, and contact lenses that make the eyes appear larger. The style is also characterized by lighter hair and sparkly accessories. The kogal trend is found in both Shibuya and Harajuku, and is influenced by a "schoolgirl" look, with participants often wearing short skirts, oversized knee-high socks. It is also characterized by artificially tanned skin or dark makeup, pale lipstick, and light hair.[19]

See also

- Culture of Japan

- Hanfu - traditional Chinese clothing

- Hanbok - traditional Korean clothing

References

- Assmann, Stephanie. "Between Tradition and Innovation: The Reinvention of the Kimono in Japanese Consumer Culture." Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture 12, no. 3 (September 2008): 359-376. Art & Architecture Source, EBSCOhost (accessed November 1, 2016)

- "Ryukyu and Ainu Textiles". kyohaku.go.jp. Kyoto National Museum. Archived from the original on 10 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- Boivin, Mai. "Okinawa Traditional Costume – Ryuso". insideokinawa.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- "Traditional Costume that Represents Okinawa's Culture and National Features, the "Ryusou"". okinawatravelinfo.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016.

- English, Bonnie. Japanese fashion designers : the work and influence of Issey Miyake, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo. n.p.: Oxford ; New York : Berg, 2011., 2011. Ignacio: USF Libraries Catalog, EBSCOhost (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Rybalko, Svitlana. "JAPANESE TRADITIONAL RAIMENT IN THE CONTEXT OF EMERGENT CULTURAL PARADIGMS." Cogito (2066-7094) 4, no. 2 (June 2012): 112-123. Humanities Source, EBSCOhost (accessed October 29, 2016)

- Valk, Julie. "The 'Kimono Wednesday' protests: identity politics and how the kimono became more than Japanese." Asian Ethnologyno. 2 (2015): 379. Literature Resource Center, EBSCOhost (accessed October 31, 2016).

- Jackson, Anna. "Kimono: Fashioning Culture by Liza Dalby". Rev. of Kimono: Fashioning Culture. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 58 (1995): 419-20. JSTOR. Web. 6 Apr. 2015.

- Dalby, Liza. (Mar 1995) "Kimono: Fashioning Culture".

- Goldstein-Gidoni, O. (1999). Kimono and the construction of gendered and cultural identities. Ethnology, 38 (4), 351-370.

- Grant, P. (2005). Kimonos: the robes of Japan. Phoebe Grant’s Fascinating Stories of World Cultures and Customs, 42.

- Ashikari, M. (2003). The memory of the women’s white faces: Japanese and the ideal image of women. Japan Forum, 15 (1), 55.

- Yamaka, Norio. (Nov 9 2012) The Book of Kimono.

- Nakagawa, K. Rosovsky, H. (1963). The case of the dying kimono: the influence of changing fashions on the development of the Japanese woolen industry. The Business History Review, 37 (1/2), 59-68

- Spacey, John (July 11, 2015). "16 Traditional Japanese Fashions". Japan Talk. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- Foley, Valerie. "Western fashion, Eastern look: the influence of the kimono and the qipau." Surface Design Journal 24, no. 1 (September 1, 1999): 23-29. Bibliography of Asian Studies, EBSCOhost (accessed November 3, 2016).

- Carpenter, John T. "Weaving Kimono Back into the Fabric of Japanese Art History." Orientations (October 2014): 1-5. Art & Architecture Source, EBSCOhost (accessed November 9, 2016).

- Aliyaapon, Jiratanatiteenun, et al. "The Transformation of Japanese Street Fashion between 2006 and 2011." Advances In Applied Sociology no. 4 (2012): 292. Airiti Library eBooks & Journals - 華藝線上圖書館, EBSCOhost (accessed October 29, 2016).

- Black, Daniel. "Wearing Out Racial Discourse: Tokyo Street Fashion and Race as Style." Journal of Popular Culture 42, no. 2 (April 2009): 239-256. Humanities Source, EBSCOhost (accessed November 16, 2016).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clothing of Japan. |