Harajuku

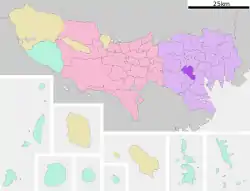

Harajuku (原宿, [haɾa(d)ʑɯkɯ] (![]() listen)) is a district in Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan. Harajuku is the common name given to a geographic area spreading from Harajuku Station to Omotesando, corresponding on official maps of Shibuya ward as Jingūmae 1 chōme to 4 chōme. In popular reference, Harajuku also encompasses many smaller backstreets such as Takeshita Street and Cat Street spreading from Sendagaya in the north to Shibuya in the south.[1]

listen)) is a district in Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan. Harajuku is the common name given to a geographic area spreading from Harajuku Station to Omotesando, corresponding on official maps of Shibuya ward as Jingūmae 1 chōme to 4 chōme. In popular reference, Harajuku also encompasses many smaller backstreets such as Takeshita Street and Cat Street spreading from Sendagaya in the north to Shibuya in the south.[1]

Harajuku is known internationally as a center of Japanese youth culture and fashion.[2] Shopping and dining options include many small, youth-oriented, independent boutiques and cafés, but the neighborhood also attracts many larger international chain stores with high-end luxury merchandisers extensively represented along Omotesando.

Harajuku Station on the JR East Yamanote Line and Meiji-jingumae 'Harajuku' Station served by the Tokyo Metro Chiyoda Line and Tokyo Metro Fukutoshin Line also act as gateways to local attractions such as the Meiji Shrine, Yoyogi Park and Yoyogi National Gymnasium, making Harajuku and its environs one of the most popular destinations in Tokyo for both domestic and international tourists.

History

Pre-Edo period

In the pre-Edo period, the area that came to be known as Harajuku was a small post town on the Kamakura Highway. It was said that in the Gosannen War, Minamoto no Yoshiie mustered his soldiers in this area and the hill here is called Seizoroi-saka (current Jingūmae 2 chōme). It is said that as the Igagoe reward for delivering Ieyasu Tokugawa safely from Sakai to Mikawa in the 1582 Honno-ji Incident, Onden-mura (隠田村) together with Harajuku-mura (原宿村) were given to the Iga ninja in 1590.

In the Edo period, an Iga clan residence was put in Harajuku to defend Edo, due to its strategic location south of the Koshu Road. Other than the mansion of the Hiroshima Domain feudal lord Asano (current Jingūmae 4 and 5 chōme), there were many mansions of shogunate retainers.

The livelihood of the farmers consisted mainly of rice cleaning and flour milling with the watermill at the Shibuya River. However, due to the poor quality of the land, production never succeeded and the villages never prospered. It is said that local farmers often performed rain-making invocations at local shrines in an attempt to improve their fortunes. There are also the tales Oyama-Afuri Shrine of Tanzawa and Worship on the day trip to Mt Haruna remaining.

Meiji Restoration to the end of the Second World War (1868 – 1945)

At the start of the Meiji period in 1868, the land around Harajuku Village was owned by the shogunate. In November of the same year, the towns and villages of Shibuya Ward, including Harajuku Village, were placed under the jurisdiction of the Tokyo Prefecture.

In 1906, Harajuku Station was opened as a part of the expansion of the Yamanote Line. In 1919, with the establishment of Meiji Shrine, Omotesando was widened and reordered as a formal approach route.

In 1943, the Tōgō Shrine was built and consecrated in honor of Imperial Japanese Navy Marshal-Admiral Marquis Tōgō Heihachirō.

In the final period of the Pacific War in 1945, much of the area was burned to the ground during the Great Tokyo Air Raid.

1945 to 1970

During the postwar occupation, military housing in the area named Washington Heights was constructed on land now occupied by Yoyogi Park and the Yoyogi National Gymnasium. Shops that appealed to the US soldiers and their families, such as Kiddyland, Oriental Bazaar, and the Fuji Tori, opened along Omotesando during this period.

In 1964, swimming, diving, and basketball events for the Tokyo Olympics were held at nearby Yoyogi National Gymnasium.

In 1965, the name of the area in the Japanese address system was officially changed from Harajuku to Jingumae. The name Harajuku has persisted due to the earlier naming of the nearby JR East Harajuku Station. Prior to 1965, Onden, referred to the low-lying area close to Meiji Street and the Shibuya River while "Harajuku" referred to the northern end of Omotesando, the plateau around Aoyama, currently known as Jingu-mae block 2, a large area of Jingu-mae block 3, and the plateau extending behind Togo Shrine in Jingu-mae block 1. The area from Harajuku station to the area surrounding Takeshita Street was called "Takeshita-cho".

1970s and 1980s

Coming into the 1970s, fashion-obsessed youth culture experienced a transition from Shinjuku to Harajuku, then to Shibuya. Palais France, a building that sold fashion clothing and accessories, furniture, and other goods, was constructed on Meiji Street near the exit of Takeshita Street. In 1978, the fashion building Laforet Harajuku was opened; thus, Harajuku came to be widely known as a fashion and retail center.

In the 1980s, Takeshita Street became known for teenage street dancing groups called takenoko-zoku.

From 1977, a Sundays only pedestrian precinct was established by closing local roads. This produced a surge in people gathering close to entrances of Yoyogi Park to watch Rock 'n' Rollers and other new bands performing impromptu open air gigs. In the peak period, crowds of up to 10,000 people would gather. In 1998,[3] the Sundays only pedestrian paradise was abolished.

1990s to present

In the 1990s and 2000s, with the rise of fast fashion, there was an influx of international fashion brand flagship store openings including Gap Inc., Forever 21, Uniqlo, Topshop and H&M. At the same time, new independent fashion trend shops spread into the previously residential areas of Jingumae 3 and 4 chome, with this area becoming known as Ura-Harajuku. (The "Harajuku Backstreets").

In 2006, Omotesando Hills opened replacing the former Dojunkai apartments on Omotesando.

In 2008, the Tokyo Metro Fukutoshin Line opened providing an alternative metro access linking Harajuku to Shibuya and Ikebukuro.

2019 New Year's Day vehicle attack

During the early morning of January 1, 2019, a 21-year-old man named Kazuhiro Kusakabe drove his Kei car into the crowd of pedestrians celebrating New Year's Day on Takeshita Street. The man claimed his actions were a terrorist attack, and later stated that his intention was to retaliate against the usage of the death penalty. The man attempted to flee from the scene but was soon apprehended by authorities in a nearby park.[4][5]

Sightseeing and local landmarks

Harajuku is a retail fashion and dining destination in its own right, but still earns much of its wider reputation as a gathering place for fans and aficionados of Japanese street fashion and associated subcultures. Jingu Bashi, the pedestrian bridge between Harajuku Station and the entrance to the Meiji Shrine used to act as a gathering place on Sundays to showcase some of the more theatrical styles.[6] Another gathering place was the lower part of Omotesandō avenue, as it used to be pedestrian-only ("Hokosha Tengoku") on Sundays.[7]

Other local landmarks include:

- Meiji Shrine, a large Shinto shrine located in an evergreen forest and dedicated to the deified spirits of Emperor Meiji and his wife, Empress Shōken.

- Yoyogi Park

- Yoyogi National Gymnasium, designed by Kenzo Tange to host swimming and diving events at the 1964 Summer Olympics.

- Omotesando

- Takeshita Street

- Ura-Harajuku

- Laforet Harajuku

- Omotesando Hills

- Tōgō Shrine

- Ukiyo-e Ōta Memorial Museum of Art

- Nezu Museum

Former landmark buildings

- Dojunkai Apartments, a 1927 building replaced in 2005 by Tadao Ando designed Omotesando Hills

- Drive-in Route 5 (Now LaforetHarajuku)

- Octagonal Pavilion (the only Korean BBQ restaurant in Harajuku district in the 1960s; presently the Octagonal Building)

- Palais France

- Harajuku Central Apartments (demolished)

- Hanae Mori Building (demolished)

- Omotesando Vivre

- Mother and Child Department Store Harajuku Carillon (Now Forever 21)

- WC Harajuku Wego store by Chinatsu Wakatsuki

- P.G.C.D. Head Office

- Menard BilecHarajukuLuseine Store

- N's game Omotesando branch

- Resona Bank Harajuku Branch (Now I.T.'S. International)

- Kokudo Head Office

- Bureau of Transportation Hospital (Now the Bureau of Transportation, Tokyo Metropolitan Government)

- Kawaii Monster Cafe is designed by designer Sebastian Masuda and presents a variety of unique menus.

Transport

Rail

Road

- Meiji Street

- Omotesando Street

- Gaien-nishi Street

In popular culture

- Scottish band Belle and Sebastian referenced Harajuku in their song "I'm a Cuckoo" on their 2003 album Dear Catastrophe Waitress with the line "I'd rather be in Tokyo / I'd rather listen to Thin Lizzy-o / And watch the Sunday gang in Harajuku / There's something wrong with me / I'm a cuckoo".

- In 2004 and 2005, Gwen Stefani appearing in concert on her Harajuku Lovers Tour and in music videos with her Harajuku Girls backup dancers attracted much attention and some controversy[8] highlighting aspects of stylized Harajuku teen fashion.

- Musical entertainer Kyary Pamyu Pamyu has been described as the "Harajuku Pop Princess" in reference to her costumes inspired by Harajuku street styles.[9][10]

- Harajuku is used as the setting in the 2017 anime series, Urahara.

- "Harajuku" is the title of a 2018 movie about a 15-year old girl who wants to run away to Tokyo from her home in Norway. [11]

See also

- Fruits (magazine), photo magazine covering Harajuku street fashion

References

- "JNTO Official Guide". Japanese National Tourism Organization. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- "Time Out Tokyo". 50 Things to do in Harajuku. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- "0Terebi Last days of Harajuku Hokoten (Japanese only)". 0Terebi. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- "8 injured as man rams car into pedestrians in Harajuku in 'retaliation for execution'". Japan Today.

- Euan McKirdy and Junko Ogura. "Tokyo car attack: Driver hits New Year's revelers in Harajuku". CNN.

- "Lonely Planet Online Guide". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- Bain, Marc. "Japan's wild, creative Harajuku street style is dead. Long live Uniqlo — Quartz". qz.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ChinatownConnection.com article Retrieved on March 14, 2009.

- J-Pop Star Kyary Pamyu Pamyu Debuts in New York City - Photos. MTV.

- "Wacky J-pop Princess, Kyary Pamyu Pamyu, Goes Dubstep". popdust.com. 12 May 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- IMDb.com Harajuku 2018 movie

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harajuku. |

Tokyo/Harajuku travel guide from Wikivoyage

Tokyo/Harajuku travel guide from Wikivoyage- Harajuku photos and guide

- Japan-guide: Harajuku