Jimmie Rodgers (country singer)

James Charles Rodgers (September 8, 1897 – May 26, 1933) was an American singer-songwriter and musician who rose to popularity in the late 1920s. Widely regarded as "the Father of Country Music",[1] he is best known for his distinctive rhythmic yodeling. Unusual for a music star of his era, Rodgers rose to prominence based upon his recordings, among country music's earliest, rather than concert performances – which followed to similar public acclaim.

Jimmie Rodgers | |

|---|---|

Rodgers in 1931 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | James Charles Rodgers |

| Born | September 8, 1897 Meridian, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | May 26, 1933 (aged 35) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Genres | Country, blues, folk |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments | Vocals, acoustic guitar, tenor banjo |

| Years active | 1910–1933 |

| Labels | Victor |

| Associated acts | The Tenneva Ramblers, The Ramblers, Louis Armstrong, Will Rogers |

| Website | www |

He has been cited as an inspiration by many artists and inductees into various halls of fame across both country music and the blues, in which he was also a pioneer. Among his other popular nicknames are "The Singing Brakeman" and "The Blue Yodeler".

Early years

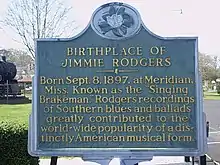

According to tradition, Rodgers' birthplace is usually listed as Meridian, Mississippi; however, in documents Rodgers signed later in life, his birthplace was listed as Geiger, Alabama, the home of his paternal grandparents.[2] Yet historians who have researched the circumstances of that document, including Nolan Porterfield and Barry Mazor, continue to identify Pine Springs, Mississippi, just north of Meridian, as his genuine birthplace. Rodgers' mother died when he was about six or seven years old, and Rodgers, the youngest of three sons, spent the next few years living with various relatives in southeast Mississippi and southwest Alabama, near Geiger. In the 1900 Census for Daleville, Lauderdale County, Mississippi, Jimmie's mother, Eliza (Bozeman) Rodgers, was listed as already having had seven children, with four of them still living at that date. Jimmie (called "James" in the census) was probably born sixth of the seven children. He eventually returned home to live with his father, Aaron Rodgers, a maintenance-of-way foreman on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, who had settled with a new wife in Meridian.

Rodgers' ancestral origins and heritage are uncertain, though records and his mother´s maiden name show his lineage to include some measure of English and probably German or Dutch ancestry.[3]

Career

Beginning

Rodgers' affinity for entertaining came at an early age, and the lure of the road was irresistible to him. By age 13, he had twice organized and begun traveling shows, only to be brought home by his father. His father found Rodgers his first job working on the railroad, as a water boy. Here he was further taught to pick and strum by rail workers and hobos. As a water boy, he would have been exposed to the work chants of the African-American railroad workers, known as gandy dancers.[4][5] A few years later, he became a brakeman on the New Orleans and Northeastern Railroad, a position formerly held by his oldest brother, Walter, who had been promoted to conductor on the line running between Meridian and New Orleans.

In 1924 at age 27, Rodgers was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The disease temporarily ended his railroad career, but at the same time gave him the chance to get back into the entertainment industry. He organized a traveling road show and performed across the southeastern United States until he was forced home after a cyclone destroyed his tent. He returned to railroad work as a brakeman in Miami, Florida, but eventually his illness cost him his job. He relocated to Tucson, Arizona, and was employed as a switchman by the Southern Pacific Railroad. He kept the job for less than a year, and the Rodgers family (which by then included wife Carrie and daughter Anita) settled back in Meridian in early 1927.

Success

Rodgers decided to travel to Asheville, North Carolina, later that same year. On April 18, 1927, at 9:30 pm, Jimmie, and Otis Kuykendall performed for the first time on WWNC, Asheville's first radio station. A few months later, Rodgers recruited a group from Bristol, Tennessee, called the Tenneva Ramblers, and secured a weekly slot on the station as "The Jimmie Rodgers Entertainers".

In late July 1927, Rodgers' bandmates learned that Ralph Peer, a representative of the Victor Talking Machine Company, was coming to Bristol to hold an audition for local musicians, later to become known as the Bristol sessions. Rodgers and the group arrived in Bristol on August 3, 1927, and auditioned for Peer in an empty warehouse. Peer agreed to record them the next day. As the band discussed how they would be billed on the record, an argument ensued, the band dissolved, and Rodgers arrived at the recording session the next morning alone, or, as later stated in an on-camera interview[6] with Claude Grant of the Tenneva Ramblers. Rodgers had taken some guitars on consignment from music shops and sold them, but never paid the stores back. The band broke up in disagreement over it. On Wednesday, August 4, Jimmie Rodgers completed his first session for Victor in Bristol. It lasted from 2:00 pm to 4:20 pm and yielded two songs: "The Soldier's Sweetheart" and "Sleep, Baby, Sleep". For the test recordings, Rodgers received $100.

The recordings were released on October 7, earning modest success. In November, Rodgers, determined more than ever to make it in entertainment, headed to New York City in an effort to arrange another session with Peer.

Rodgers requested that his sister-in-law, Elsie McWilliams, a musician, help him write some songs.[7][8] She would become his most frequent "songwriting partner."[9] She cowrote or wrote nearly 40 songs for Rodgers.[10]

Rodgers went to the Victor studios in Camden, New Jersey and recorded four more sides, including "Blue Yodel". Better known as "T for Texas", it featured a yodel Rogers claimed to have learned "after he caught a troupe of Swiss emissaries doing a demonstration at a church."[5] In the next two years this recording sold nearly half a million copies, rocketing Rodgers to stardom. After this he determined when Peer and Victor would record him, and sold out shows whenever and wherever he played.[11]

Over the next few years, Rodgers stayed very busy. He did a movie short for Columbia Pictures, The Singing Brakeman, which today appears on the DVD and VHS compilation "Times Ain't Like They Used To Be: Early Rural & Popular Music From Rare Original Film Masters 1928–35" [12] and on YouTube, and made various recordings across the country. He performed on a bill with humorist Will Rogers as part of a Red Cross tour across the Midwest.

On July 16, 1930, he recorded "Blue Yodel No. 9" with Louis Armstrong on trumpet and Armstrong's wife Lil on piano.[13] A song written by Clayton McMichen and recorded as "Prohibition Has Done Me Wrong" was not issued, possibly because of copyright conflicts with Columbia, though to Juanita McMichen Lynch, Peer felt it was "too controversial for the times." The master was put aside and subsequently lost.

Later years

Rodgers' penultimate recordings were made in August 1932 in Camden, and the tuberculosis clearly was getting the better of him. He had given up touring by that time, but did have a weekly radio show in San Antonio, Texas, where he had relocated when "T for Texas" ("Blue Yodel Number 1") became a hit. It was not in Rodgers' make-up to stay still, though, and his constant touring and recording schedule only hurt his chances of recovery.

With the country in the grip of the Great Depression, the expense of making field recordings resulted in the practice quickly fading. So, in May 1933, Rodgers traveled again to New York City for a group of sessions beginning May 17. He started these recordings alone and completed four songs on the first day. When he returned to the studio after a day's rest he had to record sitting down, and soon retired to his hotel in hopes of regaining enough energy to finish the songs he had been rehearsing. The recording engineer hired two session musicians to help Rodgers when he returned a few days later. Together they recorded a few songs, including "Mississippi Delta Blues". For his last recording of the session Rodgers chose to perform alone, and as a matching bookend to his career recorded "Years Ago".

During this final recording session Rodgers was so weakened from years of fighting tuberculosis that he had a nurse accompanying him on May 24, and needed to rest on a cot between songs.[1][14] He died of tuberculosis in a New York hotel two days later. His body was placed in a train in a pearl grey coffin and sent back to his home in Meridian, Mississippi. He was buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in Meridian.[15]

Jimmie Rodgers made a surprise comeback in 1955 when country star Hank Snow, his band The Rainbow Ranch Boys, and guitarist Chet Atkins recorded new instrumental backings to Rodgers's old solo performances. These were issued by RCA Victor and credited to "Jimmie Rodgers and the Rainbow Ranch Boys."

Personal life

Rodgers married Carrie Cecil Williamson (1902–1961).[16] The couple had two daughters, Carrie Anita Rodgers (1921–1993)[17] (known as Anita),[18] and June Rebecca Rodgers, who died at 6 months in 1923.[19] Earnings from his recordings at the peak of his career enabled Rodgers to build his "dreamhouse" for his family in Kerrville, Texas, a location chosen partly for health reasons.[18]

Always a man of the people, Rodgers maintained friendships with his old pals and band mates throughout his short life and was noted for his charming, upbeat personality. While on tour, Rodgers became legendary for his generosity to strangers, his habit of giving free impromptu performances, and for his willingness to socialize with his fans.

Rodgers was a guest at the Taft Hotel in New York City in May 1933 while working on several days of studio recordings. After completing them he died there on May 26, 1933 from a pulmonary hemorrhage[1] brought on by tuberculosis. He was 35 years old.[5] At that time he accounted for fully 10% of RCA Victor's sales[5] in a drastically depressed record market.

Legacy

When the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum was established in 1961, Rodgers was enshrined alongside music publisher and songwriter Fred Rose and iconic singer-songwriter Hank Williams. Rodgers was elected to the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970 and, as an early influence, to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1986. "Blue Yodel No. 9" was selected as one of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll. Rodgers was ranked No. 33 on CMT's 40 Greatest Men of Country Music in 2003.

Meridian, Mississippi's Jimmie Rodgers Memorial Festival has been held annually during May since 1953 to honor the anniversary of Rodgers' death.

A song "Chemirocha III" collected by ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey in 1950 from the Kipsigis tribe was written in honor of Jimmie Rodgers. The song's title is an approximation of the musician's name.[5] According to legend, tribe members were exposed to Rodgers' music through British soldiers during World War II. Impressed by his yodeling, they envisioned Rodgers as "a faun, half-man and half-antelope."[20]

Both Gene Autry and future Louisiana governor Jimmie Davis (said to have been author of "You Are My Sunshine") began their careers as Jimmie Rodgers copyists, and Merle Haggard, Hank Snow, and Lefty Frizzell later did tribute albums. Haggard's, titled Same Train, A Different Time: Merle Haggard Sings The Great Songs Of Jimmie Rodgers, was released in 1969. Haggard also covered "No Hard Times" and "T.B. Blues" on his best-selling live albums Okie from Muskogee (1969) and Fightin' Side of Me (1970). Ernest Tubb considered Rodgers an idol and began each episode of his radio show Midnite Jamboree with a Rodgers recording, a tradition that the Jamboree has continued after Tubb's death.

Rodgers' "Blue Yodel No. 1 (T for Texas)" was covered by Lynyrd Skynyrd on its live album One More from the Road. Lead singer Ronnie Van Zant was quoted at a July 13, 1977 concert in Asbury Park, New Jersey as saying that the band had "always been interested in old country music" like Jimmie Rodgers and Merle Haggard before launching into playing "T For Texas".[21] Lynyrd Skynyrd has also named both Haggard and Rodgers in their song "Railroad Song" ("I'm going to ride this train, Lord, until I find out, what Jimmie Rodgers and The Hag was all about"). Tompall Glaser also covered the song on country music's first million-selling album, Wanted! The Outlaws.

Rodgers' finger picking technique and vocal arrangements had a major influence to a young John Fahey. His reaction to hearing "Blue Yodel No. 7" inspired him to become a guitar player. "It reach out and grabbed me and it has never let go of me." [22]

In 1997 Bob Dylan put together a tribute compilation of major artists covering Rodgers' songs, The Songs of Jimmie Rodgers, A Tribute (Sony – ASIN B000002BLD). The artists included Bono, Alison Krauss & Union Station, Jerry Garcia, Dickey Betts, Dwight Yoakam, Aaron Neville, John Mellencamp, Willie Nelson and others.[23] Dylan had earlier remarked, "The songs were different than the norm. They had more of an individual nature and an elevated conscience... I was drawn to their power."[24]

Fellow Meridian, Mississippi, native Steve Forbert's tribute album to Jimmie Rodgers, Any Old Time, was nominated for a 2004 Grammy Award in the best traditional folk category.

On May 24, 1978, the United States Postal Service issued a 13-cent commemorative stamp honoring Rodgers, the first in its long-running Performing Arts Series. The stamp was designed by Jim Sharpe, and depicted Rogers with brakeman's outfit and guitar, standing in front of a locomotive giving his famous "two thumbs up" gesture.

Not just a country artist, Rodgers was one of the biggest stars of American music between 1927 and 1933, arguably doing more to popularize blues than any other performer of his time.[23] The 2009 book Meeting Jimmie Rodgers: How America's Original Roots Music Hero Changed the Pop Sounds of a Century tracks Rodgers influence through a broad range of musical genres. He was influential to Ozark poet Frank Stanford, who composed a series of "blue yodel" poems, and a number of later blues artists, including Muddy Waters, Big Bill Broonzy,[25] and Howlin' Wolf (Chester Arthur Burnett). Rodgers was Burnett's childhood idol. When he tried to emulate Rodgers's yodel his efforts sounded more like a growl or a howl. "I couldn't do no yodelin'," Barry Gifford quoted him as saying in Rolling Stone, "so I turned to howlin'. And it's done me just fine."[26]

Rodgers' influence can also be heard in artists including blues musician Tommy Johnson, the Mississippi Sheiks, and Mississippi John Hurt, whose "Let the Mermaids Flirt With Me" is based on Rodgers' hit "Waiting for a Train". Elvis Presley was also quoted as mentioning Rodgers as an important influence, stating he was a big fan.[27] Jerry Lee Lewis listed Rodgers as a major stylist and covered several of his songs. Moon Mullican, Tommy Duncan and many other western swing singers also were influenced by Rogers. Gene Autry's earlier material largely copied Rodgers' blues records, & also included covers of his songs, for example "Jimmie the kid". Johnny Cash (who said the first record he ever heard was Jimmie Rodgers, and covered Rodgers' "In The Jailhouse Now") tried for to emulate Rodgers' signature yodel on a duet of "Hey, Porter" with Marty Stuart on his 1982 album Busy Bee Cafe with Earl Scruggs on banjo. Cash admitted that he can't yodel "like Jimmie Rodgers used to."

The 1982 film Honkytonk Man, directed by and starring Clint Eastwood, was loosely based on Rodgers' life.

In the book, Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music, the song "T.B. Blues" is presented as one of the first truly autobiographical songs.

On May 28, 2010, Slim Bryant, the last surviving singer to have made a recording with Rodgers, died at the age of 101. The pair recorded Bryant's song "Mother, the Queen of My Heart" in 1932. The Union, a collaborative album between Elton John and Leon Russell, featured a song entitled "Jimmie Rodgers' Dream".

On May 3, 2007, Rodgers was honored with a marker on the Mississippi Blues Trail in his hometown of Meridian, the first outside of the Mississippi Delta.[28] In May 2010 a marker on the Mississippi Country Music Trail was erected near Rodgers' gravesite.

In 2013, Rodgers was posthumously inducted to the Blues Hall of Fame.[29]

Recordings

References

- "Jimmie Rodgers Biography". Songwriters Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on February 18, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- Petition for Membership (dated: October 20, 1930), Bluebonnet Lodge No. 1219, San Antonio, Texas; and Interview (6/2006) with James A. Skelton, Pres. of the Jimmie Rodgers Memorial Foundation, Meridian, Mississippi.

- "Jimmie Rodgers Genealogy Records". Ancestry.com.

- "In the Country of Country". The New York Times. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- Petrusich, Amanda (February 16, 2017). "Recordings of Kenya's Kipsigis Tribe". The New Yorker. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- "Interview BL-16 to 19". ETSU.edu. Interviewed by Claude Grant.

- Chadbourne, Eugene. "Elsie McWilliams". All Music. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- "Country Songwriter Elsie McWilliams". Chicago Tribune. January 1, 1986. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Wade, Howard Mitchell (July 1, 2012). "Jimmie Rodgers: The Life and Times of America's Blue Yodeler". Journal of American Folklore. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2016 – via HighBeam Research.

- Mazor, Barry (2009). Meeting Jimmie Rodgers: How America's Original Roots Music Hero Changed the Pop Sounds of a Century. Oxford University Press. pp. 305. ISBN 9780199716661.

- "USA " Mademoiselle Montana's Yodel Heaven". Mademoisellemontana.wordpress.com. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- "Early Rural & Popular Music From Rare Original Film Masters 1928–35". Yazoo Records. Archived from the original on January 28, 2012. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- "Jimmie Rodgers & Louis Armstrong: Blue Yodel No. 9". jazz.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- "Jimmie Rodgers: The Father of Country Music". Mississippi History Now. May 26, 1933. Archived from the original on October 7, 2010. Retrieved August 20, 2010 – via mshistory.k12.ms.us.

- PBS America: part 1 Rub, by Ken Burns

- "Carrie Cecil Williamson Rodgers". FindAGrave.com. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- "Carrie Anita Rodgers Court". FindAGrave.com. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- Martin, Leroy (December 8, 2015). "Mrs. Jimmie Rodgers, Epilogue". The Lafourche Gazette. Larose, Louisiana. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- "June Rebecca Rodgers". FindAGrave.com. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- "In A Kenyan Village, A 65-Year-Old Recording Comes Home". NPR.org. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- "Lynyrd Skynyrd-T For Texas-1977". YouTube. November 17, 2007. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- Lowenthal, Steve. Dance of death : the life of John Fahey, American guitarist. Chicago, Illinois. ISBN 9781613745205. OCLC 879576380.

- Barretta, Scott (August 29, 2008). "Jimmie Rodgers – This Week on Highway 61". highway61radio.com. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- Du Noyer, Paul (2003). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Music (1st ed.). Fulham, London: Flame Tree Publishing. p. 186. ISBN 1-904041-96-5.

- Fry, Robbie. ""Big Bill" Broonzy". Encyclopediaofarkansas.net. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- Taylor, B. Kimberly. "Howlin' Wolf Biography". Musician Guide. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- Matthew-Walker 1979, p. 3

- Brown, Ida. "Meridian Star – Jimmie Rodgers honored with Blues Trail Marker". Meridianstar.com. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- "2013 Blues Hall of Fame Inductees Announced". Blues.org. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

Bibliography

- Porterfield, Nolan (2007). Jimmie Rodgers: The Life and Times of America's Blue Yodeler. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 0-252-06268-X

- Porterfield, Nolan (1998). "Jimmie Rodgers". The Encyclopedia of Country Music. Paul Kinsgbury, Editor. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 453–455. ISBN 0-19-511671-2.

- Wolfe, Charles K., and Ted Olson (2005). The Bristol Sessions: Writings About the Big Bang of Country Music. McFarland & Co., Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-1945-6.

- Mazor, Barry (2009). Meeting Jimmie Rodgers: How America's Original Roots Music Hero Changed the Pop Sounds of a Century. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532762-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jimmie Rodgers (country singer). |

- Official website

- Nashville Songwriters Foundation

- Hall of Fame inductee

- Neal, Jocelyn R. The Songs of Jimmie Rodgers. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009.

- Jimmie Rodgers discography at Discogs

- Mazor, Barry. Meeting Jimmie Rodgers. New York., Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Waiting For A Train. A stage musical celebrating the life and times of Jimmie Rodgers, by Doug Pote.

- Jimmie Rodgers at Find a Grave

- Jimmie Rodgers recordings at the Discography of American Historical Recordings.