Araucaria bidwillii

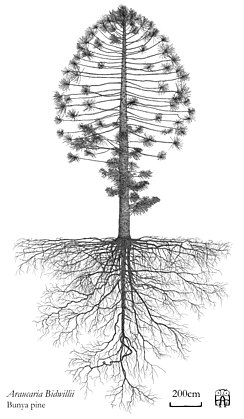

Araucaria bidwillii, commonly known as the bunya pine and sometimes referred to as the false monkey puzzle tree, is a large evergreen coniferous tree in the plant family Araucariaceae. It is found naturally in south-east Queensland Australia and two small disjunct populations in north eastern Queensland's World Heritage listed Wet Tropics. There are many old planted specimens in New South Wales, and around the Perth, Western Australia metropolitan area. They can grow up to 30–45 m (98–148 ft). The tallest presently living is one in Bunya Mountains National Park, Queensland which was reported by Robert Van Pelt in January 2003 to be 169 feet (51.5 m) in height.[2]

| Bunya pine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Araucariaceae |

| Genus: | Araucaria |

| Section: | A. sect. Bunya |

| Species: | A. bidwillii |

| Binomial name | |

| Araucaria bidwillii Hook., 1843 | |

The bunya pine is the last surviving species of the Section Bunya of the genus Araucaria. This section was diverse and widespread during the Mesozoic with some species having cone morphology similar to A. bidwillii, which appeared during the Jurassic. Fossils of Section Bunya are found in South America and Europe. The scientific name honours the botanist John Carne Bidwill, who came across it in 1842 and sent the first specimens to Sir William Hooker in the following year.[3]

Naming and description

The bunya, bonye, bunyi or bunya-bunya in various Australian Aboriginal languages was colloquially named the Bunya Pine by Europeans. However, Araucaria bidwillii is not a pine tree (of the genus Pinus). It belongs to the same genus as the monkey puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana) and is sometimes referred to as the "false monkey puzzle tree".[4][5]

The Bunya tree grows to a height of 30–45 metres, and the cones, which contain the edible kernels, are the size of soccer balls.[6]

The 1889 book The Useful Native Plants of Australia records that "The cones shed their seeds, which are two to two and a-half inches long by three-quarters of an inch broad ; they are sweet before being perfectly ripe, and after that resemble roasted chestnuts in taste. They are plentiful once in three years, and when the ripening season arrives, which is generally in the month of January.[7]

The trees pollinate in South East Queensland in September/October and the cones fall 17 to 18 months later in late January to early March from the coast to the current Bunya Mountains. When there is heavy rainfall or drought, pollination may vary.

Distribution

Native in Queensland, historically trees were found in populations recorded as abundant and widespread in suitable habitats of South East Queensland and Wide Bay-Burnett (regions). In these regions of Queensland the natural ecosystems growing Bunya Pines have sustained European agricultural occupation and have been fragmented now into the areas of the Blackall Range, Bunya Mountains, upper Brisbane River reaches and upper Mary River valley. Natural ecosystems having Bunya pines are found again approximately 1,500 km (930 mi) to the north, in the wet tropics region of north eastern Queensland. There the species natural populations are rare and restricted. Two outlying restricted populations are known in the Cannabullen Falls and Mount Lewis areas.[8][9]

A. bidwillii has a limited distribution within Australia in part because of the drying out of Australia with loss of rainforest and poor seed dispersal. The remnant sites at the Bunya Mountains and Mount Lewis in Queensland have genetic diversity. The cones are large, soft-shelled and nutritious and fall intact to the ground beneath the tree before dehiscing. The suggestion that extinct large animals – perhaps dinosaurs and later, large mammals – may have been dispersers for the Bunya is reasonable, given the seeds' size and energy content, but difficult to confirm given the incompleteness of the fossil record for coprolites.

At the start of European occupation, A. bidwillii occurred in great abundance in southern Queensland, to the extent that a Bunya reserve was proclaimed in 1842 (revoked 1860) to protect its habitat.[10] The tree once grew as large groves or sprinkled regularly as an emergent species throughout other forest types on the Upper Stanley and Brisbane Rivers, Sunshine Coast hinterland (especially the Blackall Range near Montville and Maleny), and also towards and on the Bunya Mountains. Today, the species is usually encountered as very small groves or single trees in its former range, except on and near the Bunya Mountains, where it is still fairly prolific.

Ecology

A. bidwillii has unusual cryptogeal seed germination in which the seeds develop to form an underground tuber from which the aerial shoot later emerges. The actual emergence of the seed is then known to occur over several years presumably as a strategy to allow the seedlings to emerge under optimum climatic conditions or, it has been suggested, to avoid fire. This erratic germination has been one of the main problems in silviculture of the species.

The cones are 20–35 cm (7.9–13.8 in) in diameter, and can weigh as much as 18 kg (40 lb)[11] and are opened by large birds, such as cockatoos, or disintegrate when mature to release the large 3–4 cm (1.2–1.6 in) seeds or nuts.

Although there are no reported dispersal agents for the seeds of A. bidwillii, macropods and various species of rats are known as predators of the seeds and tubers. The bush rat (Rattus fuscipes) was observed caching bunya seeds some distance uphill from parent trees, possibly allowing ridge-top germination. Brushtail possums (Trichosurus spp.) were mentioned as carrying the seeds up trees. In a study in 2006, the short-eared possum (Trichosurus caninus) was shown to disperse the seed of A. bidwillii.

Natural populations of this species have been reduced in extent and abundance through exploitation for its timber, the construction of dams and historical clearing. Most populations are now protected in formal reserves and national parks.

A recent problem in small forestry plantations of A. bidwilli in Southeast Queensland is the introduction of red deer (Cervus elaphus). Red deer, unlike possums and rodents, eat bunya cones while still intact, preventing their dispersal.[12]

Cultural significance

The bunya, bonye, bunyi or bunya-bunya tree produces edible kernels. The ripe cones fall to the ground. Each segment contains a kernel in a tough protective shell, which will split when boiled or put in a fire. The flavour of the kernel is similar to a chestnut.

The cones were a very important food source for native Australians – each Aboriginal family would own a group of trees and these would be passed down from generation to generation. This is said to be the only case of hereditary personal property owned by the Aboriginal people.[13]

After the cones had fallen and the fruit was ripe, large festival harvest would sometimes occur, between two and seven years apart. The people of the region would set aside differences and gather in the Bon-yi Mountains (Bunya Mountains) to feast on the kernels. The local people, who were bound by custodial obligations and rights, sent out messengers to invite people from hundreds of kilometres to meet at specific sites. The meetings involved Aboriginal ceremonies, dispute settlements and fights, marriage arrangements and the trading of goods.[14]

In what was probably Australia's largest Indigenous event, diverse tribes – up to thousands of people – once travelled great distances (from as far as Charleville, Bundaberg, Dubbo and Grafton) to the gatherings. They stayed for months, to celebrate and feast on the bunya nut. The bunya gatherings were an armistice accompanied by much trade exchange, and discussions and negotiations over marriage and regional issues. Due to the sacred status of the bunyas, some tribes would not camp amongst these trees. Also in some regions, the tree was never to be cut.[15]

Representatives from many different groups from across southern Queensland and northern New South Wales would meet to discuss important issues relating to the environment, social relationships, politics and The Dreaming lore, feasting and sharing dance ceremonies. Many conflicts would be settled at this event, and consequences for breaches of laws were discussed.[16]

A Bunya festival was recorded by Thomas (Tom) Petrie (1831–1910), who went with the Aboriginal people of Brisbane at the age of 14 to the festival at the Bunya Range (now the Blackall Range in the hinterland area of the Sunshine Coast). His daughter, Constance Petrie, put down his stories in which he said that the trees fruited at three-year intervals.[17] The three-year interval may not be correct. Ludwig Leichhardt wrote in 1844 of his expedition to the Bunya feast.[18]

The Aboriginal people's close association with the trees led to colonial authorities in 1842 prohibiting settlers from occupying land or cutting timber within a proclaimed Bunya district.[10] The district was abolished in 1860[10] and the Aboriginal people were eventually driven out of the forests along with the ability to run the festivals. The forests were felled for timber and cleared to make way for cultivation.[14]

Today

Indigenous groups such as the Wakawaka, Githabul, Kabi Kabi, Jarowair, Goreng goreng, Butchulla, Quandamooka, Baruŋgam , Yiman and Wulili have continued cultural and spiritual connections to the Bunya Mountains to this day. A number of strategies including the use of traditional ecological knowledge have been incorporated into the current management practices of the national park and conservation reserves with the Bunya Murri Ranger project currently operating in the mountains.[19][20]

Uses

Indigenous Australians eat the nut of the bunya tree both raw and cooked (roasted, and in more recent times boiled), and also in its immature form. Traditionally, the nuts were additionally ground and made into a paste, which was eaten directly or cooked in hot coals to make bread. The nuts were also stored in the mud of running creeks, and eaten in a fermented state. This was considered a delicacy.

Apart from consuming the nuts, Indigenous Australians ate bunya shoots, and utilised the tree's bark as kindling.

Bunya nuts are still sold as a regular food item in grocery stalls and street-side stalls around rural southern Queensland. Some farmers in the Wide Bay/ Sunshine Coast regions have experimented with growing bunya trees commercially for their nuts and timber.

Bunya timber was and is still highly valued as "tonewood" for stringed instruments' sound boards since the first European settlers. Since the mid-1990s, the Australian company Maton has used bunya for the soundboards of its BG808CL Performer acoustic guitars. The Cole Clark company (also Australian) uses bunya for the majority of its acoustic guitar soundboards. The timber is valued by cabinet makers and woodworkers, and has been used for that purpose for over a century.

However, its most popular use is as a 'bushfood' by indigenous foods enthusiasts. A huge variety of home-invented recipes now exists for the bunya nut; from pancakes, biscuits and breads, to casseroles, to 'bunya nut pesto' or hoummus. The nut is considered nutritious, with a unique flavour similar to starchy potato and chestnut.

When the nuts are boiled in water, the water turns red, making a flavoursome tea.

The nutritional content of the bunya nut is: 40% water, 40% complex carbohydrates, 9% protein, 2% fat, 0.2% potassium, 0.06% magnesium.[21] It is also gluten free, making bunya nut flour a substitute for people with gluten intolerance.

Cultivation

Bunya nuts are slow to germinate. A set of 12 seeds sown in Melbourne took an average of about six months to germinate (with the first germinating in 3 months) and only developed roots after 1 year. The first leaves form a rosette and are dark brown. The leaves only turn green once the first stem branch occurs. Unlike the mature leaves, the young leaves are relatively soft. As the leaves age they become very hard and sharp. Cuttings can be successful, though they must be taken from erect growing shoots, as cuttings from side shoots will not grow upright.

In the highly variable Australian climate, the spread of actual emergence of the bunya maximises the possibility of at least successful replacement of the parent tree. A test of germination was carried out by Smith starting in 1999.[22] Seeds were extracted from two mature cones collected from the same tree, a cultivated specimen at Petrie, just north of Brisbane (originally the homestead of Thomas Petrie, the son of the first European to report the species). One hundred apparently full seeds were selected and planted into 30 cm by 12 cm plastic tubes commercially filled with sterile potting mix in early February 1999. These were then placed in a shaded area and watered weekly. Four tubes were lost due to being knocked over. Of a total of 100 seeds placed, 87 germinated. The tubes were checked monthly for emergence over 3 years. Of these seeds, 55 emerged from April to December, 1999; 32 emerged from January to September in 2000, 1 seed emerged in January 2001, and the last 1 appeared in February 2001.[22]

Once established, bunyas are quite hardy and they can be grown as far south as Hobart in Australia (42° S) and Christchurch in New Zealand (43° S)[23] and (at least) as far north as Sacramento in California (38° N)[24] and Coimbra (in the botanical garden) and even in Dublin area in Ireland (53ºN) in a microclimate protected from arctic winds and moderated by the Gulf Stream.[25] They will reach a height of 35 to 40 metres, and live for about 500 years.

Architecture

Auracaria bidwillii, like many species from the Araucariaceae or Abies families, has the particularity of changing its structural model during its growth : its grows following a perfect Massart's model to gradually changes to Rauh when old.[26]

In popular culture

A specimen of Auracaria bidwillii in East Los Angeles, California is featured in Taylor Hackford's 1993 film Blood In Blood Out as a touchstone for the main characters.[27] The tree, known as "El Pino" ("the pine" in Spanish), has become famous from this association, and is visited by international fans of the film.[27] A late-2020 prank claiming the tree would be cut down incited a brief panic locally.[28]

References

- Thomas, P. (2011). "Araucaria bidwillii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T42195A10660714. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T42195A10660714.en.

- "Araucaria bidwillii (Bunya pine) description". conifers.org.

- "Figure and Description of a new species of Araucaria, from Moreton Bay, New Holland, detected by J. T. Bidwill, Esq". London Journal of Botany. II: 498–506. 1843.

- "False monkey puzzle". Stuff. From Waikato Times. 25 August 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2020.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Araucaria bidwillii Bunya-Bunya, Monkey Puzzle Tree, False Monkey Puzzle PFAF Plant Database". Plants for a future. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "Araucaria bidwillii". anpsa.org.au.

- J. H. Maiden (1889). The useful native plants of Australia : Including Tasmania. Turner and Henderson, Sydney.

- "Conifer Database in Catalogue of Life". Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Hyland, B. P. M.; Whiffin, T.; Zich, F. A.; et al. (December 2010). "Factsheet – Araucaria bidwillii". Australian Tropical Rainforest Plants (6.1, online version RFK 6.1 ed.). Cairns, Australia: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), through its Division of Plant Industry; the Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research; the Australian Tropical Herbarium, James Cook University. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- E. G. Heap (1965). "In the Wake of the Raftsmen: A Survey of Early Settlement in the Maroochy District up to the Passing of Macalister's Act (1868) [Part I]". Queensland Heritage. 1 (3): 3–16.

- "Man severely hurt by massive pine cone in San Francisco sues government and park service". CBS San Francisco. 13 October 2015.

- Smith I.R (2007) Feral deer in south-east Queensland: a right royal nuisance. Newsletter of the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland (WPSQ) Summer Quarterly No. 191.

- Hook (2004). "Araucaria bidwillii – Hook".

- Assimilating the bunya forests Anna Haebich Centre for Public Culture and Ideas, Griffith University, Queensland (viewed 16 February 2012)

- Jerome, P., 2002. Boobarran Ngummin: the Bunya Mountains. [Opening address to the Bunya Symposium (2002: Griffith University).].

- Aboriginal Ceremonies (PDF) (Report). Resource: Indigenous Perspectives: Res008. Queensland Government and Queensland Studies Authority. February 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- "Bunya Feast". anpsa.org.au. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- "Ludwig Leichhardt (on the bushfood trail)". Australian Bushfoods Magazine (1). 1997. ISSN 1447-0489. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Markwell Consulting, 2010. Bonye Buru Booburrgan Ngmmunge – Bunya Mountains Aboriginal Aspirations and Caring for Country Plan (Plan).

- Queensland Government, 2012. Bunya Mountains National Park Management Statement 2012 (Management Plan). Department of National Parks, Recreation, Sport and Racing.

- "Composition of the Bunya nut". Australian Bushfoods magazine. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- Smith, Ian R.; Butler, Don (2009), "The Bunya Pine – the ecology of Australia's other 'Living Fossil' Araucarian – Dandabah Area – Bunya Mountains, South East Queensland, Australia.", in Bieleski, R. L.; Wilcox, M. D. (eds.), Araucariacea : proceedings of the 2002 Araucariaceae Symposium, Araucaria-Agathis-Wollemia, International Dendrology Society, pp. 287–298, ISBN 978-0-473-15226-0, OCLC 614167748

- "Araucaria araucana and A. bidwillii by Michael A. Arnold" (PDF). Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- "Araucaria bidwillii". University of Hamburg. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- "Climatic zone plants". Earlscliffe. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- Hallé, Francis (2018). "L'Arbre et sa Structure (Lecture, Ver de Terre production)" – via YouTube.

- Becerra, Hector. "Great Read: A tree's cinematic fame continues to grow in East L.A." Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- Arellano, Gustavo. "Column: People came by to pay final respects to this East L.A. tree that went Hollywood. Too soon?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

Footnotes

- Conifer Specialist Group (1998). "Araucaria bidwillii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998. Retrieved 12 May 2006.

- Haines R. J. (1983) Embryo development and anatomy in Araucaria Juss. Australian Journal of Botany. 31, 125–140.

- Haines R. J. (1983) Seed development in Araucaria Juss. Australian Journal of Botany. 31, 255–267.

- Hernandez-Castillo, G. R., Stockey R. A.(2002) Palaeobotany of the Bunya Pine In (Ed. Anna Haebich) ppl 31–38. 'On the Bunya Trail' Queensland Review – Special Edition, Volume 9, No. 2, November 2002 (University of Queensland Press: St Lucia).

- Petrie C. C. (ed) (1904), Tom Petrie's Reminiscences of Early Queensland (Brisb, 1904)

- Pye M.G., Gadek P. A. (2004) Genetic diversity, differentiation and conservation in Araucaria bidwillii (Araucariaceae), Australia's Bunya pine. Conservation Genetics. 5, 619–629.

- Smith I. R., Withers K., Billingsley J. (2007) Maintaining the Ancient Bunya Tree (Araucaria bidwillii Hook.) – Dispersal and Mast Years. 5th Southern Connection Conference, Adelaide, South Australia, 21–25 January 2007.

- Smith I. R. (2004) Regional Forest Types-Southern Coniferous Forests In 'Encyclopedia of Forest Sciences' (eds. Burley J., Evans J., Youngquist J.) Elsevier: Oxford. pp 1383–1391.

- Smith I. R., Butler D (2002) The Bunya in Queensland's Forests, In (Ed. Anna Haebich) pp. 31–38. 'On the Bunya Trail' Queensland Review – Special Edition, Volume 9, No. 2, November 2002 (University of Queensland Press: St Lucia).

- Conifer Specialist Group (1998). "Araucaria bidwillii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998. Retrieved 12 May 2006.

- Conifer Specialist Group (1998). "Araucaria bidwillii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998. Retrieved 12 May 2006.

External links

- Bunya Pine, Aboriginal Use of Native Plants