Recreational drug use

Recreational drug use is the use of a psychoactive drug to induce an altered state of consciousness, by modifying the perceptions, feelings, and emotions of the user. When a psychoactive drug enters the user's body, it induces an intoxicating effect. Generally, recreational drugs are in three categories: depressants (drugs that induce a feeling of relaxation and calmness); stimulants (drugs that induce a sense of energy and alertness); and hallucinogens (drugs that induce perceptual distortions such as hallucination).

In popular practice, recreational drug use generally is a tolerated social behaviour, rather than perceived as the medical condition of self-medication.[1] However, heavy use of some drugs is socially stigmatized. Many people also use prescribed and controlled depressants such as opioids, along with opiates, and benzodiazepines.

Recreational drugs include alcohol (as found in beer, wine, and distilled spirits); cannabis (legal to possess nationally in certain countries and state/province-wide or locally in others) and hashish; nicotine (tobacco); caffeine (coffee, tea, and soft drinks); prescription drugs; and the controlled substances listed as controlled drugs in the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961) and the Convention on Psychotropic Substances (1971) of the United Nations. What controlled substances are considered generally unlawful to possess varies by country, but usually includes methamphetamine, heroin, cocaine, LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, MDMA and club drugs. In 2015, it was estimated that about 50% of people aged 15 to 65 had used controlled drugs at least once (158 million to 351 million).[2]

Reasons for use

.jpg.webp)

Many researchers have explored the etiology of recreational drug use. Some of the most common theories are: genetics, personality type, psychological problems, self-medication, gender, age, instant gratification, basic human need, curiosity, rebelliousness, a sense of belonging to a group, family and attachment issues, history of trauma, failure at school or work, socioeconomic stressors, peer pressure, juvenile delinquency, availability, historical factors, or sociocultural influences.[4] There has not been agreement around any one single cause. Instead, experts tend to apply the biopsychosocial model. Any number of these factors are likely to influence an individual's drug use as they are not mutually exclusive.[4][5] Regardless of genetics, mental health or traumatic experiences, social factors play a large role in exposure to and availability of certain types of drugs and patterns of drug use.[4][6]

According to addiction researcher Martin A. Plant, many people go through a period of self-redefinition before initiating recreational drug use. They tend to view using drugs as part of a general lifestyle that involves belonging to a subculture that they associate with heightened status and the challenging of social norms. Plant says, "From the user's point of view there are many positive reasons to become part of the milieu of drug taking. The reasons for drug use appear to have as much to do with needs for friendship, pleasure and status as they do with unhappiness or poverty. Becoming a drug taker, to many people, is a positive affirmation rather than a negative experience".[4]

Evolution

Anthropological research has suggested that humans "may have evolved to counter-exploit plant neurotoxins". The ability to use botanical chemicals to serve the function of endogenous neurotransmitters may have improved survival rates, conferring an evolutionary advantage. A typically restrictive prehistoric diet may have emphasised the apparent benefit of consuming psychoactive drugs, which had themselves evolved to imitate neurotransmitters.[7] Chemical–ecological adaptations, and the genetics of hepatic enzymes, particularly cytochrome P450, have led researchers to propose that "humans have shared a co-evolutionary relationship with psychotropic plant substances that is millions of years old."[8]

Risks

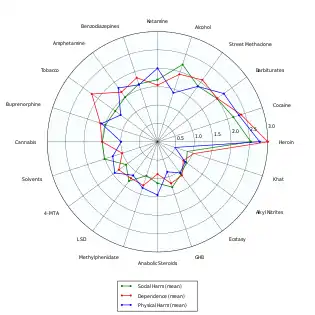

Severity and type of risks that come with recreational drug use vary widely with the drug in question and the amount being used. There are many factors in the environment and within the user that interact with each drug differently. Overall, some studies suggest that alcohol is one of the most dangerous of all recreational drugs; only heroin, crack cocaine, and methamphetamines are judged to be more harmful. However, studies which focus on a moderate level of alcohol consumption have concluded that there can be substantial health benefits from its use, such as decreased risk of cardiac disease, stroke and cognitive decline.[10][11][12][13] This claim has been disputed. Researcher David Nutt stated that these studies showing benefits for "moderate" alcohol consumption lacked control for the variable of what the subjects were drinking, beforehand.[14] Experts in the UK have suggested that some drugs that may be causing less harm, to fewer users (although they are also used less frequently in the first place), include cannabis, psilocybin mushrooms, LSD, and ecstasy. These drugs are not without their own particular risks.[15]

Responsible use

The concept of "responsible drug use" is that a person can use drugs recreationally or otherwise with reduced or eliminated risk of negatively affecting other aspects of one's life or other people's lives. Advocates of this philosophy point to the many well-known artists and intellectuals who have used drugs, experimentally or otherwise, with few detrimental effects on their lives. Responsible drug use becomes problematic only when the use of the substance significantly interferes with the user's daily life.

Responsible drug use advocates that users should not take drugs at the same time as activities such as driving, swimming, operating machinery, or other activities that are unsafe without a sober state. Responsible drug use is emphasized as a primary prevention technique in harm-reduction drug policies. Harm-reduction policies were popularized in the late 1980s, although they began in the 1970s counter-culture, when cartoons explaining responsible drug use and the consequences of irresponsible drug use were distributed to users.[16] Another issue is that the illegality of drugs in itself also causes social and economic consequences for those using them—the drugs may be "cut" with adulterants and the purity varies wildly, making overdoses more likely—and legalization of drug production and distribution would reduce these and other dangers of illegal drug use.[17] Harm reduction seeks to minimize the harm that can occur through the use of various drugs, whether legal (e.g., alcohol and nicotine), or illegal (e.g., heroin and cocaine). For example, people who take drugs intravenously (crack cocaine, heroin) can minimize harm to both themselves and members of the community through proper injecting technique, using new needles and syringes each time, and proper disposal of all injecting equipment.

Prevention

In efforts to curtail recreational drug use, governments worldwide introduced several laws prohibiting the possession of almost all varieties of recreational drugs during the 20th century. The West's "War on Drugs" however, is now facing increasing criticism. Evidence is insufficient to tell if behavioral interventions help prevent recreational drug use in children.[18]

One in four adolescents has used an illegal drug and one in ten of those adolescents who need addiction treatment get some type of care.[19] School-based programs are the most commonly used method for drug use education despite the success rates of these intervention programs this success is highly dependent on the commitment of participants. The success of these program is very limited[20]

Studies have also shown that home intervention is also effective in decreasing the appeal of drugs.

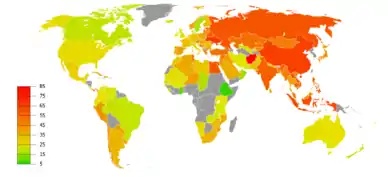

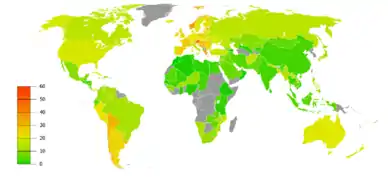

Demographics

Australia

Alcohol is the most widely used drug in Australia.[23] 86.2% of Australians aged 12 years and over have consumed alcohol at least once in their lifetime, compared to 34.8% of Australians aged 12 years and over who have used cannabis at least once in their lifetime.[23]

United States

In the 1960s, the number of Americans who had tried cannabis at least once increased over twentyfold. In 1969, the FBI reported that between the years 1966 and 1968, the number of arrests for marijuana possession, which had been outlawed throughout the United States under Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, had increased by 98%.[24] Despite acknowledgement that drug use was greatly growing among America's youth during the late 1960s, surveys have suggested that only as much as 4% of the American population had ever smoked marijuana by 1969.[25] By 1972, however, that number would increase to 12%.[25] That number would then double by 1977.[25]

The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 classified marijuana along with heroin and LSD as a Schedule I drug, i.e., having the relatively highest abuse potential and no accepted medical use.[26] Most marijuana at that time came from Mexico, but in 1975 the Mexican government agreed to eradicate the crop by spraying it with the herbicide paraquat, raising fears of toxic side effects.[26] Colombia then became the main supplier.[26] The "zero tolerance" climate of the Reagan and Bush administrations (1981–93) resulted in passage of strict laws and mandatory sentences for possession of marijuana and in heightened vigilance against smuggling at the southern borders. The "war on drugs" thus brought with it a shift from reliance on imported supplies to domestic cultivation (particularly in Hawaii and California).[26] Beginning in 1982, the Drug Enforcement Administration turned increased attention to marijuana farms in the United States,[26] and there was a shift to the indoor growing of plants specially developed for small size and high yield.[26] After over a decade of decreasing use, marijuana smoking began an upward trend once more in the early 1990s,[26] especially among teenagers,[26] but by the end of the decade this upswing had leveled off well below former peaks of use.[26]

Society and culture

Many movements and organizations are advocating for or against the liberalization of the use of recreational drugs, notably cannabis legalization. Subcultures have emerged among users of recreational drugs, as well as among those who abstain from them, such as teetotalism and "straight edge".

The prevalence of recreational drugs in human societies is widely reflected in fiction, entertainment, and the arts, subject to prevailing laws and social conventions. In video games, for example, drugs are portrayed in a variety of ways: including power-ups (cocaine gum replenishes stamina in Red Dead Redemption 2), obstacles to be avoided (such as the Fuzzies in Super Mario World 2: Yoshi's Island that distort the player's view when accidentally consumed), items to be bought and sold for in-game currency (coke dealing is big part of Scarface: The World Is Yours). In 1997's Fallout, drugs ("chems" in the game) can fill the role of any above mentioned.

Common recreational drugs

The following substances are used recreationally:[27]

- Alcohol: Most drinking alcohol is ethanol, CH

3CH

2OH. Drinking alcohol creates intoxication, relaxation and lowered inhibitions. It is produced by the fermentation of sugars by yeasts to create wine, beer, and distilled liquor (e.g., vodka, rum, gin, etc.). In most areas of the world, it is legal for those over a certain age (18 in most countries). It is an IARC Group 1 carcinogen and a teratogen.[28] Alcohol withdrawal can be life-threatening.[29] - Amphetamines: Used recreationally to provide alertness and a sense of energy. Prescribed for ADHD, narcolepsy, depression and weight loss. A potent central nervous system stimulant, in the 1940s and 50s methamphetamine was used by Axis and Allied troops in World War II, and, later on, other armies, and by Japanese factory workers. It increases muscle strength and fatigue resistance and improves reaction time.[30] Methamphetamine use can be neurotoxic, which means it damages dopamine neurons.[31] As a result of this brain damage, chronic use can lead to post acute withdrawal syndrome.[32]

- Caffeine: Often found in coffee, black tea, energy drinks, some soft drinks (e.g., Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Mountain Dew, among others), and chocolate. It is the world's most widely consumed psychoactive drug, but has only mild dependence liability for long-term users.[33]

- Cannabis: Its common forms include marijuana and hashish, which are smoked or eaten. It contains at least 85 cannabinoids. The primary psychoactive component is THC, which mimics the neurotransmitter anandamide, named after the Hindu ananda, "joy, bliss, delight".

- Cocaine: It is available as a white powder, which is insufflated ("sniffed" into the nostrils) or converted into a solution with water and injected. A popular derivative, crack cocaine is typically smoked. When transformed into its freebase form, crack, the cocaine vapour may be inhaled directly. This is thought to increase bioavailability, but has also been found to be toxic, due to the production of methylecgonidine during pyrolysis.[34][35][36]

- MDMA: Commonly known as ecstasy, it is a common club drug in the rave scene.

- Electronic cigarette: A large proportion of e-cigarette use is recreational.[37] Most e-cigarette liquids contain nicotine, but the level of nicotine varies depending on user-preference and manufacturers.[38] Nicotine is highly addictive,[39][40][41] comparable to heroin or cocaine.[42] E-cigarettes are being used to inhale MDMA, cocaine powder, crack cocaine, synthetic cathinones, mephedrone, α-PVP, synthetic cannabinoids, opioids, heroin, fentanyl, tryptamines, and ketamine.[43]

- Ketamine: An anesthetic used legally by paramedics and doctors in emergency situations for its dissociative and analgesic qualities and illegally in the club drug scene.

- Lean: A liquid drug mixture made when mixing cough syrup, sweets, soft drinks and codeine. It originated in the 1990s in Houston. Ever since then, this drug usage has grown and is often used at parties and in the rave scene. Many people would get a drowsy feeling when consuming this drug.

- LSD: A popular ergoline derivative, that was first synthesized in 1938 by Albert Hofmann. However, he failed to notice its psychedelic effects until 1943.[44] In the 1950s, it was used in psychological therapy, and, covertly, by the CIA in Project MKULTRA, in which the drug was administered to unwitting US and Canadian citizens. It played a central role in 1960s 'counter-culture', and was banned in October 1968 by US President Lyndon B Johnson.[45][46]

- Nitrous oxide: legally used by dentists as an anxiolytic and anaesthetic, it is also used recreationally by users who obtain it from whipped cream canisters (whippets or whip-its) (see inhalant), as it causes perceptual effects, a "high" and at higher doses, hallucinations.

- Opiates and opioids: Available by prescription for pain relief. Commonly used opioids include oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, fentanyl, heroin, methadone, and morphine. Opioids have a high potential for addiction and have the ability to induce severe physical withdrawal symptoms upon cessation of frequent use. Heroin can be smoked, insufflated or turned into a solution with water and injected. Percocet is a prescription opioid containing oxycodone and acetaminophen.

- Psilocybin mushrooms: This hallucinogenic drug was an important drug in the psychedelic scene. Until 1963, when it was chemically analysed by Albert Hofmann, it was completely unknown to modern science that Psilocybe semilanceata ("Liberty Cap", common throughout Europe) contains psilocybin, a hallucinogen previously identified only in species native to Mexico, Asia, and North America.[47]

- Tobacco: Nicotiana tabacum. Nicotine is the key drug contained in tobacco leaves, which are either smoked, chewed or snuffed. It contains nicotine, which crosses the blood–brain barrier in 10–20 seconds. It mimics the action of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine at nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain and the neuromuscular junction. The neuronal forms of the receptor are present both post-synaptically (involved in classical neurotransmission) and pre-synaptically, where they can influence the release of multiple neurotransmitters.[48]

- Tranquilizers: barbiturates, benzodiazepines (e.g. alprazolam, diazepam, etc.)(commonly prescribed for anxiety disorders; known to cause dementia and post acute withdrawal syndrome)

- "Bath salts": slang term that generally refers to substituted cathinones such as Mephedrone and Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), but not always

- DMT – primary ingredient in ayahuasca, can also be smoked in a crack pipe; briefly (c. 30 minutes) causes a "total loss of connection to external reality"[49]

- Peyote: This hallucinogen contains mescaline, native to southwestern Texas and Mexico

- Salvia divinorum: This hallucinogenic Mexican herb in the mint family; not considered recreational, most likely due to the nature of the hallucinations (legal in some jurisdictions)

- Synthetic cannabis: "Spice", "K2", JWH-018, AM-2201

- Quaaludes: A popular club drug in the 1970s. No longer prescribed or manufactured in many countries but remains popular in South Africa.[50][51]

Routes of administration

Drugs are often associated with a particular route of administration. Many drugs can be consumed in more than one way. For example, marijuana can be swallowed like food or smoked, and cocaine can be "sniffed" in the nostrils, injected, or, with various modifications, smoked.

- inhalation: all intoxicative inhalants (see below) that are gases or solvent vapours that are inhaled through the trachea, as the name suggests

- insufflation: also known as "sniffing", or "snorting", this method involves the user placing a powder in the nostrils and breathing in through the nose, so that the drug is absorbed by the mucous membranes. Drugs that are "sniffed", or "snorted", include powdered amphetamines, cocaine, heroin, ketamine, MDMA, snuff tobacco

- Subcutaneous injection: also known as Skin popping. Injection of drug into the third lowest layer of skin.

- Intramuscular injection: injection of drug into a muscle.

- intravenous injection (see also the article Drug injection): the user injects a solution of water and the drug into a vein, or less commonly, into the tissue. Drugs that are injected include morphine and heroin, less commonly other opioids. Stimulants like cocaine or methamphetamine may also be injected. In rare cases, users inject other drugs.

- oral intake: caffeine, ethanol, cannabis edibles, psilocybin mushrooms, coca tea, poppy tea, laudanum, GHB, ecstasy pills with MDMA or various other substances (mainly stimulants and psychedelics), prescription and over-the-counter drugs (ADHD and narcolepsy medications, benzodiazepines, anxiolytics, sedatives, cough suppressants, morphine, codeine, opioids and others)

- sublingual: substances diffuse into the blood through tissues under the tongue. Many psychoactive drugs can be or have been specifically designed for sublingual administration, including barbiturates, benzodiazepines,[52] opioid analgesics with poor gastrointestinal bioavailability, LSD blotters, coca leaves, some hallucinogens. This route of administration is activated when chewing some forms of smokeless tobacco (e.g. dipping tobacco, snus).

- intrarectal: administering into the rectum, most water-soluble drugs can be used this way

- smoking (see also the section below): tobacco, cannabis, opium, crystal meth, phencyclidine, crack cocaine and heroin (diamorphine as freebase) known as chasing the dragon

- transdermal patches with prescription drugs: e.g. methylphenidate (Daytrana) and fentanyl

Many drugs are taken through various routes. Intravenous route is the most efficient, but also one of the most dangerous. Nasal, rectal, inhalation and smoking are safer. The oral route is one of the safest and most comfortable, but of little bioavailability.

Types

Depressants

Depressants are psychoactive drugs that temporarily diminish the function or activity of a specific part of the body or mind.[53] Colloquially, depressants are known as "downers", and users generally take them to feel more relaxed and less tense. Examples of these kinds of effects may include anxiolysis, sedation, and hypotension. Depressants are widely used throughout the world as prescription medicines and as illicit substances. When these are used, effects may include anxiolysis (reduction of anxiety), analgesia (pain relief), sedation, somnolence, cognitive/memory impairment, dissociation, muscle relaxation, lowered blood pressure/heart rate, respiratory depression, anesthesia, and anticonvulsant effects. Depressants exert their effects through a number of different pharmacological mechanisms, the most prominent of which include facilitation of GABA or opioid activity, and inhibition of adrenergic, histamine or acetylcholine activity. Some are also capable of inducing feelings of euphoria (a happy sensation). The most widely used depressant by far is alcohol.

Stimulants or "uppers", such as amphetamines or cocaine, which increase mental or physical function, have an opposite effect to depressants.

Depressants, in particular alcohol, can cause psychosis. A 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis by Murrie et al. found that the rate of transition from opioid, alcohol and sedative induced psychosis to schizophrenia was 12%, 10% and 9% respectively.[54]

Antihistamines

Antihistamines (or "histamine antagonists") inhibit the release or action of histamine. "Antihistamine" can be used to describe any histamine antagonist, but the term is usually reserved for the classical antihistamines that act upon the H1 histamine receptor. Antihistamines are used as treatment for allergies. Allergies are caused by an excessive response of the body to allergens, such as the pollen released by grasses and trees. An allergic reaction causes release of histamine by the body. Other uses of antihistamines are to help with normal symptoms of insect stings even if there is no allergic reaction. Their recreational appeal exists mainly due to their anticholinergic properties, that induce anxiolysis and, in some cases such as diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine, and orphenadrine, a characteristic euphoria at moderate doses. High dosages taken to induce recreational drug effects may lead to overdoses. Antihistamines are also consumed in combination with alcohol, particularly by youth who find it hard to obtain alcohol. The combination of the two drugs can cause intoxication with lower alcohol doses.

Hallucinations and possibly delirium resembling the effects of Datura stramonium can result if the drug is taken in much higher than therapeutical dosages. Antihistamines are widely available over the counter at drug stores (without a prescription), in the form of allergy medication and some cough medicines. They are sometimes used in combination with other substances such as alcohol. The most common unsupervised use of antihistamines in terms of volume and percentage of the total is perhaps in parallel to the medicinal use of some antihistamines to stretch out and intensify the effects of opioids and depressants. The most commonly used are hydroxyzine, mainly to stretch out a supply of other drugs, as in medical use, and the above-mentioned ethanolamine and alkylamine-class first-generation antihistamines, which are – once again as in the 1950s – the subject of medical research into their anti-depressant properties.

For all of the above reasons, the use of medicinal scopolamine for recreational uses is also seen.

Analgesics

Analgesics (also known as "painkillers") are used to relieve pain (achieve analgesia). The word analgesic derives from Greek "αν-" (an-, "without") and "άλγος" (álgos, "pain"). Analgesic drugs act in various ways on the peripheral and central nervous systems; they include paracetamol (also known in the US as acetaminophen), the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as the salicylates, and opioid drugs such as hydrocodone, codeine, heroin and oxycodone. Some further examples of the brand name prescription opiates and opioid analgesics that may be used recreationally include Vicodin, Lortab, Norco (hydrocodone), Avinza, Kapanol (morphine), Opana, Paramorphan (oxymorphone), Dilaudid, Palladone (hydromorphone), and OxyContin (oxycodone).

Tranquilizers

The following are examples of tranquilizers (GABAergics):

- Barbiturates

- Benzodiazepines

- Ethanol (drinking alcohol; ethyl alcohol)

- Nonbenzodiazepines

- Others

- carisoprodol (Soma)

- chloral hydrate

- diethyl ether

- ethchlorvynol (Placidyl; "jelly-bellies")

- gamma-butyrolactone (GBL, a prodrug to GHB)

- gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB; G; Xyrem; "Liquid Ecstasy", "Fantasy")

- glutethimide (Doriden)

- kava (from Piper methysticum; contains kavalactones)

- ketamine

- meprobamate (Miltown)

- methaqualone (Sopor, Mandrax; "Quaaludes")

- phenibut

- propofol (Diprivan)

- theanine (found in Camellia sinensis, the tea plant)

- valerian (from Valeriana officinalis)

Stimulants

Stimulants, also known as "psychostimulants",[55] induce euphoria with improvements in mental and physical function, such as enhanced alertness, wakefulness, and locomotion. Due to their effects typically having an "up" quality to them, stimulants are also occasionally referred to as "uppers". Depressants or "downers", which decrease mental or physical function, are in stark contrast to stimulants and are considered to be their functional opposites.

Stimulants enhance the activity of the central and peripheral nervous systems. Common effects may include increased alertness, awareness, wakefulness, endurance, productivity, and motivation, arousal, locomotion, heart rate, and blood pressure, and a diminished desire for food and sleep.

Use of stimulants may cause the body to significantly reduce its production of natural body chemicals that fulfill similar functions. Once the effect of the ingested stimulant has worn off the user may feel depressed, lethargic, confused, and miserable. This is referred to as a "crash", and may provoke reuse of the stimulant.

Amphetamines are a significant cause of drug-induced psychosis. Importantly, a 2019 meta-analysis found that 22% of people with amphetamine-induced psychosis transition to a later diagnosis of schizophrenia.[54]

Examples include:

- Sympathomimetics (catecholaminergics)—e.g. amphetamine, methamphetamine, cocaine, methylphenidate, ephedrine, pseudoephedrine

- Entactogens (serotonergics, primarily phenethylamines)—e.g. MDMA

- Eugeroics, e.g. modafinil

- Others

- arecoline (found in Areca catechu)

- caffeine (found in Coffea spp.)

- nicotine (found in Nicotiana spp.)

- rauwolscine (found in Rauvolfia serpentina)

- yohimbine (Procomil; a tryptamine alkaloid found in Pausinystalia johimbe)

Euphoriants

- Alcohol: "Euphoria, the feeling of well-being, has been reported during the early (10–15 min) phase of alcohol consumption" (e.g., beer, wine or spirits)[56]

- Catnip: Catnip contains a sedative known as nepetalactone that activates opioid receptors. In cats it elicits sniffing, licking, chewing, head shaking, rolling, and rubbing which are indicators of pleasure. In humans, however, catnip does not act as a euphoriant.[57]

- Cannabis: Tetrahydrocannabinol, the main psychoactive ingredient in this plant, can have sedative and euphoric properties.

- Stimulants: "Psychomotor stimulants produce locomotor activity (the subject becomes hyperactive), euphoria, (often expressed by excessive talking and garrulous behaviour), and anorexia. The amphetamines are the best known drugs in this category..."[58]

- MDMA: The "euphoriant drugs such as MDMA ('ecstasy') and MDEA ('eve')" are popular among young adults.[59] MDMA "users experience short-term feelings of euphoria, rushes of energy and increased tactility."[60]

- Opium: This "drug derived from the unripe seed-pods of the opium poppy…produces drowsiness and euphoria and reduces pain. Morphine and codeine are opium derivatives."[61]

Hallucinogens

Hallucinogens can be divided into three broad categories: psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants. They can cause subjective changes in perception, thought, emotion and consciousness. Unlike other psychoactive drugs such as stimulants and opioids, hallucinogens do not merely amplify familiar states of mind but also induce experiences that differ from those of ordinary consciousness, often compared to non-ordinary forms of consciousness such as trance, meditation, conversion experiences, and dreams.

Psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants have a long worldwide history of use within medicinal and religious traditions. They are used in shamanic forms of ritual healing and divination, in initiation rites, and in the religious rituals of syncretistic movements such as União do Vegetal, Santo Daime, Temple of the True Inner Light, and the Native American Church. When used in religious practice, psychedelic drugs, as well as other substances like tobacco, are referred to as entheogens.

Hallucinogen-induced psychosis occurs when psychosis persists despite no longer being intoxicated with the drug. It is estimated that 26% of people with hallucinogen-induced psychosis will transition to a diagnosis of schizophrenia. This is less than the transition rate of cannabis (34%) but higher than amphetamines (22%).[54]

Starting in the mid-20th century, psychedelic drugs have been the object of extensive attention in the Western world. They have been and are being explored as potential therapeutic agents in treating depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcoholism, and opioid addiction. Yet the most popular, and at the same time most stigmatized, use of psychedelics in Western culture has been associated with the search for direct religious experience, enhanced creativity, personal development, and "mind expansion". The use of psychedelic drugs was a major element of the 1960s counterculture, where it became associated with various social movements and a general atmosphere of rebellion and strife between generations.

- Deliriants

- atropine (alkaloid found in plants of the family Solanaceae, including datura, deadly nightshade, henbane and mandrake)

- dimenhydrinate (Dramamine, an antihistamine)

- diphenhydramine (Benadryl, Unisom, Nytol)

- hyoscyamine (alkaloid also found in the Solanaceae)

- hyoscine hydrobromide (another Solanaceae alkaloid)

- myristicin (found in Myristica fragrans ("Nutmeg"))

- ibotenic acid (found in Amanita muscaria ("Fly Agaric"); prodrug to muscimol)

- muscimol (also found in Amanita muscaria, a GABAergic)

- Dissociatives

- dextromethorphan (DXM; Robitussin, Delsym, etc.; "Dex", "Robo", "Cough Syrup", "DXM")

- "Triple C's, Coricidin, Skittles" refer to a potentially fatal formulation containing both dextromethorphan and chlorpheniramine.

- ketamine (K; Ketalar, Ketaset, Ketanest; "Ket", "Kit Kat", "Special-K", "Vitamin K", "Jet Fuel", "Horse Tranquilizer")

- methoxetamine (Mex, Mket, Mexi)

- phencyclidine (PCP; Sernyl; "Angel Dust", "Rocket Fuel", "Sherm", "Killer Weed", "Super Grass")

- nitrous oxide (N2O; "NOS", "Laughing Gas", "Whippets", "Balloons")

- dextromethorphan (DXM; Robitussin, Delsym, etc.; "Dex", "Robo", "Cough Syrup", "DXM")

- Psychedelics

- Phenethylamines

- 2C-B ("Nexus", "Venus", "Eros", "Bees")

- 2C-E ("Eternity", "Hummingbird")

- 2C-I ("Infinity")

- 2C-T-2 ("Rosy")

- 2C-T-7 ("Blue Mystic", "Lucky 7")

- DOB

- DOC

- DOI

- DOM ("Serenity, Tranquility, and Peace" ("STP"))

- MDMA ("Ecstasy", "E", "Molly", "Mandy", "MD", "Crystal Love")

- mescaline (found in peyote, Peruvian torch cactus and San Pedro cactus)

- Tryptamines (including ergolines and lysergamides)

- 5-MeO-DiPT ("Foxy", "Foxy Methoxy")

- 5-MeO-DMT (found in various plants like chacruna, jurema, vilca, and yopo)

- alpha-methyltryptamine (αMT; Indopan; "Spirals")

- bufotenin (secreted by Bufo alvarius, also found in various Amanita mushrooms)

- N,N-dimethyltryptamine (N,N-DMT; DMT; "Dimitri", "Disneyland", "Spice"; found in large amounts in Psychotria and in D. cabrerana)

- lysergic acid amide (LSA; ergine; found in morning glory and Hawaiian baby woodrose seeds)

- lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD; L; Delysid; "Acid", "Sid". "Cid", "Lucy", "Sidney", "Blotters", "Droppers", "Sugar Cubes")

- psilocin (found in psilocybin mushrooms)

- psilocybin (also found in psilocybin mushrooms; prodrug to psilocin)

- ibogaine (found in Tabernanthe iboga ("Iboga"))

- Phenethylamines

- Atypicals

- salvinorin A (found in Salvia divinorum, a trans-neoclerodane diterpenoid ("Diviner's Sage", "Lady Salvia", "Salvinorin"))

Inhalants

Inhalants are gases, aerosols, or solvents that are breathed in and absorbed through the lungs. While some "inhalant" drugs are used for medical purposes, as in the case of nitrous oxide, a dental anesthetic, inhalants are used as recreational drugs for their intoxicating effect. Most inhalant drugs that are used non-medically are ingredients in household or industrial chemical products that are not intended to be concentrated and inhaled, including organic solvents (found in cleaning products, fast-drying glues, and nail polish removers), fuels (gasoline (petrol) and kerosene), and propellant gases such as Freon and compressed hydrofluorocarbons that are used in aerosol cans such as hairspray, whipped cream, and non-stick cooking spray. A small number of recreational inhalant drugs are pharmaceutical products that are used illicitly, such as anesthetics (ether and nitrous oxide) and volatile anti-angina drugs (alkyl nitrites).

The most serious inhalant abuse occurs among children and teens who "[...] live on the streets completely without family ties".[62] Inhalant users inhale vapor or aerosol propellant gases using plastic bags held over the mouth or by breathing from a solvent-soaked rag or an open container. The effects of inhalants range from an alcohol-like intoxication and intense euphoria to vivid hallucinations, depending on the substance and the dosage. Some inhalant users are injured due to the harmful effects of the solvents or gases, or due to other chemicals used in the products that they are inhaling. As with any recreational drug, users can be injured due to dangerous behavior while they are intoxicated, such as driving under the influence. Computer cleaning dusters are dangerous to inhale, because the gases expand and cool rapidly upon being sprayed. In some cases, users have died from hypoxia (lack of oxygen), pneumonia, cardiac failure or arrest,[63] or aspiration of vomit.

Examples include:

- Chloroform

- Ethyl chloride

- Diethyl ether

- Ethane and ethylene

- Laughing gas (nitrous oxide)

- Poppers (alkyl nitrites)

- Solvents and propellants (including propane, butane, freon, gasoline, kerosene, toluene) and the fumes of glues containing them

List of drugs which can be smoked

Plants:

- tobacco

- cannabis

- salvia divinorum

- opium

- datura and other Solanaceae (formerly smoked to treat asthma)

- possibly other plants (see the section below)

Substances (also not necessarily psychoactive plants smoked with them):

- methamphetamine

- crack cocaine

- black tar heroin

- phencyclidine (PCP)

- synthetic cannabinoids (see also: synthetic cannabis)

- dimethyltryptamine (DMT)

- 5-MeO-DMT

- Bufotenine

- DiPT

- Methaqualone

- Ethanol

- Ketamine

- Heroin

- many others, including some prescription drugs

List of psychoactive plants, fungi and animals

Minimally psychoactive plants which contain mainly caffeine and theobromine:

- coffee

- tea (caffeine in tea is sometimes called theine) – also contains theanine

- guarana (caffeine in guarana is sometimes called guaranine)

- yerba mate (caffeine in yerba mate is sometimes called mateine)

- cocoa

- kola

Most known psychoactive plants:

- cannabis: cannabinoids

- tobacco: nicotine and beta-carboline alkaloids

- coca: cocaine

- opium poppy: morphine, codeine and other opiates

- salvia divinorum: salvinorin A

- khat: cathine and cathinone

- kava: kavalactones

- nutmeg: myristicin

Solanaceae plants—contain atropine, hyoscyamine and scopolamine

- datura

- deadly nightshade Atropa belladonna

- henbane

- mandrake (Mandragora)

- other Solanaceae

Other plants:

- kratom: mitragynine, mitraphylline, 7-hydroxymitragynine, raubasine and corynantheidine

- ephedra: ephedrine

- damiana

- Calea zacatechichi

- Silene capensis

- valerian: valerian (the chemical with the same name)

- various plants like chacruna, jurema, vilca, and yopo – 5-MeO-DMT

- Morning glory and Hawaiian Baby Woodrose – lysergic acid amide (LSA, ergine)

- Ayahuasca

- Tabernanthe iboga ("Iboga")—ibogaine

- Areca catechu (see: betel and paan)—arecoline

- Rauvolfia serpentina: rauwolscine

- yohimbe (Pausinystalia johimbe): yohimbine, corynantheidine

- probably many others

Fungi:

- psilocybin mushrooms: psilocybin and psilocin

- various Amanita mushrooms: muscimol

- Amanita muscaria: ibotenic acid and muscimol

- Claviceps purpurea and other Clavicipitaceae: ergotamine (not psychoactive itself but used in synthesis of LSD)

Psychoactive animals:

- hallucinogenic fish

- psychoactive toads: bufotenin, Bufo alvarius (Colorado River toad or Sonoran Desert toad) also contains 5-MeO-DMT

See also

References

- "Specialty Drug Classes That Are Costing Consumers an Arm and a Leg". The Motley Fool. 24 October 2015.

- Global Overview of Drug Demand and Supply (PDF). World Drug Report 2017. United Nations. 2017. p. 13. ISBN 978-92-1-148291-1. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Staelens, Stefanie (10 March 2015). "The Bhang Lassi Is How Hindus Drink Themselves High for Shiva". Vice.com. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- Plant, Martin A. (1980), "Drugtaking and Prevention: The Implications of Research for Social Policy", British Journal of Addiction, 75 (3): 245–254, doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1980.tb01378.x, PMID 6938224

- White, Tony (2012), Working with Drug and Alcohol Users, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, p. 77, ISBN 9780857006189

- "Department of Health | 3.1 Reasons why people use drugs". www1.health.gov.au. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Roger J Sullivan; Edward H Hagen; Peter Hammerstein (2008). "Revealing the paradox of drug reward in human evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1640): 1231–1241. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1673. PMC 2367444. PMID 18353749.

- R. J. Sullivan; E. H. Hagen (2000). "Psychotropic substance-seeking: evolutionary pathology or adaptation?" (PDF). Addiction (Abingdon, England). 97 (4): 389–400. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00024.x. PMID 11964056. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- Nutt, D; King, LA; Saulsbury, W; Blakemore, C (24 March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–53. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- Stampfer MJ, Kang JH, Chen J, Cherry R, Grodstein F (January 2005). "Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on cognitive function in women". N Engl J Med. 352 (3): 245–53. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041152. PMID 15659724.

- Hines LM, Stampfer MJ, Ma J (February 2001). "Genetic variation in alcohol dehydrogenase and the beneficial effect of moderate alcohol consumption on myocardial infarction". N Engl J Med. 344 (8): 549–55. doi:10.1056/NEJM200102223440802. PMID 11207350.

- Berger K, Ajani UA, Kase CS (November 1999). "Light-to-moderate alcohol consumption and risk of stroke among U.S. male physicians". N Engl J Med. 341 (21): 1557–64. doi:10.1056/NEJM199911183412101. PMID 10564684.

- Mukamal KJ, Conigrave KM, Mittleman MA (January 2003). "Roles of drinking pattern and type of alcohol consumed in coronary heart disease in men". N Engl J Med. 348 (2): 109–18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022095. PMID 12519921.

- Nutt, David (7 March 2011). "There is no such thing as a safe level of alcohol consumption - Professor David Nutt". The Guardian.

- ""Drug harms in the UK: a multi-criteria decision analysis", by David Nutt, Leslie King and Lawrence Phillips, on behalf of the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs". The Lancet. 2 November 2010.

- Charles E. Faupel; Alan M. Horowitz; Greg S. Weaver. The Sociology of American Drug Use. McGraw Hill. p. 366.

- "Failed states and failed policies, How to stop the drug wars". The Economist. 5 March 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- Moyer, VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force (6 May 2014). "Primary care behavioral interventions to reduce illicit drug and nonmedical pharmaceutical use in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (9): 634–9. doi:10.7326/m14-0334. PMID 24615535.

- Lord S, Marsch L (2011). "Emerging trends and innovations in the identification and management of drug use among adolescents and young adults". Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 22 (3): 649–69, xiv. PMC 4119795. PMID 22423469.

- "Error during processing". nam02.safelinks.protection.outlook.com. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- "WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008" (PDF).

- "Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004" (PDF).

- "National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2016: detailed findings". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 28 September 2017.

- David Farber (2004). The Sixties Chronicle. Legacy Publishing. p. 432. ISBN 978-1412710091.

- Decades of Drug Use: Data From the '60s and '70s Jennifer Robison, Gallup.com, 2 July 2002, Accessed 13 November 2013

- "marijuana: History of Marijuana Use". infoplease.com.

- "Commonly Used Drugs Charts". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- "Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs" (PDF).

- Trevisan, Louis A.; Boutros, Nashaat; Petrakis, Ismene L.; Krystal, John H. "Complications of Alcohol Withdrawal" (PDF). Alcohol Health and Research World. 22 (1): 61–66.

- John Philip Jenkins. "methamphetamine (drug) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Cruickshank, CC; Dyer, KR (July 2009). "A review of the clinical pharmacology of methamphetamine". Addiction. 104 (7): 1085–1099. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02564.x. PMID 19426289.

- Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "15". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Unlike cocaine and amphetamine, methamphetamine is directly toxic to midbrain dopamine neurons.

- Nestler, Eric J. (Eric Jonathan), 1954- (2009). Molecular neuropharmacology : a foundation for clinical neuroscience. Hyman, Steven E., Malenka, Robert C. (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 375. ISBN 9780071641197. OCLC 273018757.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Methylecgonidine, a Crack Cocaine Pyrolyzate". aspetjournals.org.

- British Journal of Pharmacology – Abstract of article: Evidence for cocaine and methylecgonidine stimulation of M2 muscarinic receptors in cultured human embryonic lung cells

- Fandiño, Anabel S.; Toennes, Stefan W.; Kauert, Gerold F. (1 December 2002). "Studies on Hydrolytic and Oxidative Metabolic Pathways of Anhydroecgonine Methyl Ester (Methylecgonidine) Using Microsomal Preparations from Rat Organs". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 15 (12): 1543–1548. doi:10.1021/tx0255828. PMID 12482236.

- Rahman, Muhammad; Hann, Nicholas; Wilson, Andrew; Worrall-Carter, Linda (2014). "Electronic cigarettes: patterns of use, health effects, use in smoking cessation and regulatory issues". Tobacco Induced Diseases. 12 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/1617-9625-12-21. PMC 4350653. PMID 25745382.

- Burstyn, I (9 January 2014). "Peering through the mist: systematic review of what the chemistry of contaminants in electronic cigarettes tells us about health risks". BMC Public Health. 14: 18. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-18. PMC 3937158. PMID 24406205.

- Grana, R; Benowitz, N; Glantz, SA (13 May 2014). "E-cigarettes: a scientific review". Circulation. 129 (19): 1972–86. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.114.007667. PMC 4018182. PMID 24821826.

- Holbrook, Bradley D. (2016). "The effects of nicotine on human fetal development". Birth Defects Research Part C: Embryo Today: Reviews. 108 (2): 181–92. doi:10.1002/bdrc.21128. ISSN 1542-975X. PMID 27297020.

- Siqueira, Lorena M. (2016). "Nicotine and Tobacco as Substances of Abuse in Children and Adolescents". Pediatrics. 139 (1): e20163436. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-3436. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 27994114.

- Jenssen, Brian P.; Boykan, Rachel (2019). "Electronic Cigarettes and Youth in the United States: A Call to Action (at the Local, National and Global Levels)". Children. 6 (2): 30. doi:10.3390/children6020030. ISSN 2227-9067. PMC 6406299. PMID 30791645.

- Breitbarth, Andreas K.; Morgan, Jody; Jones, Alison L. (2018). "E-cigarettes—An unintended illicit drug delivery system". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 192: 98–111. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.031. ISSN 0376-8716. PMID 30245461.

- Albert Hofmann. "LSD My Problem Child". Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- "Brecher, Edward M; et al. (1972). "How LSD was popularized". Consumer Reports/Drug Library". Druglibrary.org. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- United States Congress (24 October 1968). "Staggers-Dodd Bill, Public Law 90-639" (PDF). Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- Hofmann A, Heim R, Tscherter H (1963). "Phytochimie – présence de la psilocybine dans une espèce européenne d'agaric, le Psilocybe semilanceata Fr." [Phytochemistry – presence of psilocybin in a European agaric species, Psilocybe semilanceata Fr.]. Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences (in French) 257 (1). pp. 10–12.

- Wonnacott S (February 1997). "Presynaptic nicotinic ACh receptors". Trends in Neurosciences. 20 (2): 92–8. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10073-4. PMID 9023878. S2CID 42215860.

- "Erowid DMT (Dimethyltryptamine) Vault". Erowid.org. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- "The drug plague destroying families across South Africa". Zululand Observer. 22 May 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "Quaaludes (methaqualone) Uses, Effects & History of Abuse". Drugs.com. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "ATIVAN® 1 mg SUBLINGUAL TABLETS; ATIVAN® 2 mg SUBLINGUAL TABLETS". home.intekom.com. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- "MSDS Glossary". Archived from the original on 17 January 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Murrie, Benjamin; Lappin, Julia; Large, Matthew; Sara, Grant (16 October 2019). "Transition of Substance-Induced, Brief, and Atypical Psychoses to Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 46 (3): 505–516. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbz102. PMC 7147575. PMID 31618428.

- "Dorlands Medical Dictionary:psychostimulant".

- Morgan Christopher J.; Abdulla A.-B. Badawy (2001). "Alcohol-induced euphoria: exclusion of serotonin". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 36 (1): 22–25. doi:10.1093/alcalc/36.1.22. PMID 11139411.

- Foster, Steven (2002). A field guide to Western Medicinal Plants and Herbs. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 58. ISBN 978-0395838068.

- Alan W. Cuthbert "stimulants" The Oxford Companion to the Body. Ed. Colin Blakemore and Sheila Jennett. Oxford University Press, 2001. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 28 July 2011

- Rhodri Hayward "euphoria" The Oxford Companion to the Body. Ed. Colin Blakemore and Sheila Jennett. Oxford University Press, 2001. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 28 July 2011

- "ecstasy" World Encyclopedia. Philip's, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 28 July 2011

- "opium". World Encyclopedia. Philip's, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 28 July 2011

- "NIDA - Research Monographs - Monograph Index" (PDF). drugabuse.gov.

- Inhalants; archived at Inhalants

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Recreational drug use. |