Kallar (caste)

Kallar (or Kallan, formerly spelled as Colleries) is one of the three related castes of southern India which constitute the Mukkulathor (Thevar) confederacy.[1] The Kallar, along with the Maravar and Agamudayar, constitute a united social caste on the basis of parallel professions, though their locations and heritages are wholly separate from one another.

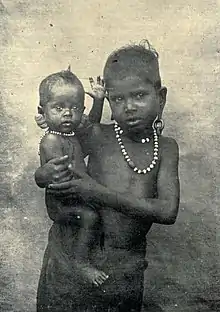

Kallar children with dilated earlobes | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Tamil Nadu | |

| Languages | |

| Tamil | |

| Religion | |

| Folk Hinduism |

Etymology

"Kallar" is a Tamil word meaning "thief". Their history has included periods of banditry.[2] Alternatively, the term 'Kallar' can mean "Master" or "Landlord",[3] Other proposed etymological origins include "black skinned", "hero", and "toddy-tappers".[4]

The anthropologist Susan Bayly notes that the name Kallar, was a title bestowed by Tamil palaiyakkarars (warrior-chiefs) on pastoral peasants who acted as their armed retainers. The majority of those poligars, who during the late 17th- and 18th-centuries controlled much of the Telugu region as well as the Tamil area, had themselves come from the Kallar, Maravar and Vatuka communities.[5] Kallar is synonymous with the western Indian term, Koli, having connotations of thievery but also of upland pastoralism.[6] According to Bayly, Kallar should be considered a "title of rural groups in Tamil Nadu with warrior-pastoralist ancestral traditions".[7]

History

Kallar served in the armies of the Chola and Pandya kings. They are predominantly found in Thanjavur, Madurai, Tiruchirappalli, Pudukkottai, Sivagangai and Theni Districts. The Thanjavur kallar today largely engage in agriculture[8] and Kallar of Tirunelveli add deva (Thevar), " god," to their names as a caste title, as also did the Pandian kings.[9]

The Thondaiman dynasty of the erstwhile Pudukkottai state hailed from the Kallar community.[10] Kallars living in the districts of Trichy, Thanjavur, Thiruvarur and Pudukkottai are using around thousand family titles like Cholangathevar, Mazhavarayar, Kadavarayar, Pallavarayar, Tondaiman, Sambuvarayar, Vandayar, Rajaliyar, Mutharaiayar etc.[11][12] Also the Pallavarayar rulers of pudukkottai belongs to kallar lineage.[13]

Based on his historical research on a south Indian Hindu kingdom ruled by members of the Kallar caste, Dirks argues that "while the brahman was superior to the king as Kallar, he was inferior to the Kallar as king.[14]

Most palayakkars in western Tirunelveli and in Ramanathapuram were "Maravar", those of Madurai, Tiruchirappalli and Thanjavur "Kallar", and those of eastern Tirunelveli, Dindigal and Coimbatore "Nayak".[15]

During Tirumala Nayaka rule, Kallar caste which controlled the outlying areas of madurai, was incorporated to the madurai kingdom because of its close association with vishnu in the form of Kallazhagar. It is worthy to mention that during chithirai festival, Kallazhagar used to be dressed like a kallar warrior. During this occasion Kalla alagar is accompanied by kallar ritualists.[16]

Bayly notes that the Kallar and Maravar identities as a caste, rather than as a title, "... were clearly not ancient facts of life in the Tamil Nadu region. Insofar as these people of the turbulent poligar country really did become castes, their bonds of affinity were shaped in the relatively recent past".[6] Prior to the late 18th-century, their exposure to Brahmanic Hinduism, the concept of varna and practices such as endogamy that define the Indian caste system was minimal. Thereafter, the evolution as a caste developed as a result of various influences, including increased interaction with other groups as a consequence of jungle clearances, state-building and ideological shifts.[5]

Maikondan was a chief of the caste of kallans lived in 17 th-century. He was a brave warrior who ruled areas around Nandavanapatti in Thanjavur. In the year of 1662, Bijapur sultans invaded Thanjavur. During this invasion maikondan fought against sultans and saved all the inhabitants of Thanjavur.[17]

The kallar domains in 1686, This was at Avur, where a line of Kallar chiefs known as the Kattalur and Perambur rajas gave their support to the missionaries' activities. Persecuted by the Thanjavur Marathas, the Christians surrendered to the kallar people in March 1745 in the Gunnampatti area of Thanjavur district.[18]

Just 50 Kallan warriors defeated the Nawab's army of 10,000 in the battle of Chunampatti, Thanjavur per a British account of 1734. Praised as lightning quick & expert horsemen.[15]

Ananda Ranga Pillai mentioned in his one of the diary note, that French government asked him to write letters to palayakkars and chiefs of tamil nadu for gaining support from them against british. The letter which was written on 24 May 1751, it was mentioned that french government has sent letters to six divisions of kallars such as Visengi Nattu Kallars, Tondimanpurattu Kallars, Alagarkoil Kallars, Piramalai Kallar, Nagamalai Range Kallars and Tannarasu Nattu Kallars.[19]

British sources often characterized the Kallars, and the related castes, as "soldiers out of work." Many Kallars had been warriors as well as peasants for the last few centuries. Kallar chieftaincies, organized into networks of nadus, controlled the region north and west of Madurai. The Nayaks attempted to pacify or subjugate them by titling Kallar chieftains, with limited success. These nadus were well outside Nayaka control, and folk songs told of fields that could not be harvested and raids by Kallar parties, who were considered sovereign and independent, in Madurai city. This situation persisted past the downfall of the Nayakas and the advent of Yusuf Khan, until the mid 18th century. Starting in 1755, the British army engaged in several brutal, bloody campaigns against the Kallars of Melur, but decades later Kallar raiding parties still posed a significant threat. In 1801, they networked with palegars of Tamil and Telugu regions to spearhead a series of revolts against British control.[20]

In 1755 AD, during a war with british kallars used a eighteen meters spears.[21] In 1759 AD, vadagarai poligar of Tirunelveli attacked Travancore with the assistance from kallars. But travancore with the help of Muhammad Yusuf Khan repulsed the forces of vadagarai and kallars.[22] In July 1759, Madurai kallars fought against british and 500 kallars were hanged to death in Thiruparankundram.[23]

During carnatic wars in 1763, british force under colonel heron looted the treasures of perumal temple in Thirumohoor. But kallars fought with british and saved the treasures of temple.[24]

By the late 18th century, the Kallars were working as kavalkarars, or watchmen, in hundreds of villages throughout southern Tamil Nadu, especially the region west of Madurai. These kavalkarars were given maniyam, rent-free land, to ensure they did their job correctly. These kaval maniyams were commonly held by palaiyakarars who used land, and shares of the crops, to maintain a small militia. A common allegation made by colonial officials was that these kavalkarars were "abusing" their position and exploiting the peasants whose livelihoods they were supposed to protect. Kallars were often also hired as mercenaries by palaiyakarars, who according to British sources, used them to loot villagers. In 1803, these rights were abolished by the East India Company and the militias were abolished. However, the kaval system was not abolished but placed under the supervision of the East India Company.[20]

Reforms in 1816 abolished the responsibility kavalkarars had towards compensation for damaged crops while keeping fees, which British sources claimed led to the kavalkarars charging exorbitant fees. By the end of the 19th century, the watchmen formed a "shadow administration." Although British claims that Kallar watchmen were operating a "protection racket" were exaggerated, the Kallar watchmen still had the power of violence over the cultivators who paid them.[20]

Around the beginning of the 20th century, the cultivators, of many communities, near Madurai staged an anti-Kallar movement against the community's authority. The reasons for the movement are complex: partly the abuse of authority shown by Kallar watchmen, partly agrarian distress, and part-personal feud. The agitations took the form of violence against the Kallars, including arson, and forcing them out of the villages. In 1918, the community was placed on the list of Criminal Tribes.[20]

Culture

Among the traditional customs of the Kallar noted by colonial officials was the use of the "collery stick" (Tamil: valai tādi, kallartādi), a bent throwing stick or "false boomerang" which could be thrown up to 100 yards (91 m).[25] Writing in 1957, Louis Dumont noted that despite the weapon's frequent mention in literature, it had disappeared amongst the Piramalai Kallar.[26]

The women of Kallar community are extraordinarily clever and they supervise household work in the absence of men. The entire household responsibility is given to kallar women. Kallar women are known for their bravery also.[27]

Diet

The Kallar were traditionally a non-vegetarian people,[28] though a 1970s survey of Tamil Nadu indicated that 30% of Kallar surveyed, though non-vegetarian, refrained from eating fish after puberty.[29] Meat, though present in the Kallar diet, was not frequently eaten but restricted to Saturday nights and festival days. Even so, this small amount of meat was sufficient to affect perceptions of Kallar social status.[26]

The guardian deity is Kattavarayan seems to have some special link with the Kallar. The kallar, although formerly a "criminal caste" regard them selves as Ksatriyas, because there are Kallar kings.[30]

Martial arts

The Kallars traditionally practised a Tamil martial art variously known as Adimurai, chinna adi and varna ati. In recent years, since 1958, these have been referred to as Southern-style Kalaripayattu, although they are distinct from the ancient martial art of Kalaripayattu itself that was historically the style found in Kerala.[31]

References

- Price, Pamela G. (1996). Kingship and Political Practice in Colonial India (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 62, 87, 193. ISBN 978-0-52155-247-9.

- Dirks, Nicholas B. (1993). The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom (2nd ed.). University of Michigan Press. p. 242. ISBN 9780472081875.

- Journal Of Madras University Vol 81. 1990. pp. 84.

- Kuppuram, G. (1988). India through the ages: history, art, culture, and religion, Volume 1. Sundeep Prakashan. p. 366. ISBN 9788185067087.

- Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6.

- Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6.

- Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 385. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6.

- Historical Dictionary of the Tamils (2nd ed.). The Scarecrow Press. 2007. p. 105. ISBN 9780810864450.

- Mateer, Samuel (1883). Native Life in Travancore. p. 387.

- Nicholas B. Dirks (1993). The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom. University of Michigan Press, 1993 - Social Science - 430 pages. p. 130. ISBN 9780472081875.

- A Manual Of The Pudukkottai State Vol.i. 1938. pp. 108.

- The East India Magazine Vol. 8. pp. 225.

- Gazetter of pudukkottai district. pp. .

- S.Sax, William. (2002). Dancing the Self. p. 131. ISBN 9780198031871.

- Ramaswami, N. S. (1984). Political History of Carnatic Under the Nawabs. p. 44&45. ISBN 9780836412628.

- Harman, William P. (1989). The Sacred Marriage of a Hindu Goddess. p. 82. ISBN 9788120808102.

- Tamilaham In The 17th Century (1956). p. 71.

- Bayly, Susan (1989). Saints, Goddesses and Kings: Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society. p. 57. ISBN 9780521891035.

- Private diary of Ananda Ranga Pillai vol.8. 1922. p. 9.

- Pandian, Anand (2005). "Securing the rural citizen". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 42 (1): 1–39. doi:10.1177/001946460504200101. ISSN 0019-4646. S2CID 143099962.

- The War Of Coromandel. p. 208.

- Yusuf Khan The Rebel Commandant. 1914. p. 99.

- Yusuf Khan : the rebel commandant. 1914. p. 97.

- "Maruthu Pandiyars".

- Sir Henry Yule; Arthur Coke Burnell (1903). Hobson-Jobson: a glossary of colloquial Anglo-Indian words and phrases, and of kindred terms, etymological, historical, geographical and discursive. J. Murray. pp. 236–. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- Dumont, Louis; Stern, A.; Moffatt, Michael (1986). A South Indian subcaste: social organization and religion of the Pramalai Kallar. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195617856.

- Muthulakshmi, R. (1997). Female Infanticide, Its Causes and Solutions. p. 12. ISBN 9788171413836.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (21 September 1989). Criminal gods and demon devotees: essays on the guardians of popular Hinduism. p. 21. ISBN 9780887069826.

- Robson, John R. K. (1980). Food, ecology, and culture: readings in the anthropology of dietary practices. p. 98. ISBN 9780677160900.

- Criminal Gods and Demon Devotees: Essays on the Guardians of Popular Hinduism. pp. 21.

- Zarilli, Philip B. (2001). "India". In Green, Thomas A. (ed.). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia. A – L. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-57607-150-2.