French East India Company

The French East India Company (French: Compagnie française pour le commerce des Indes orientales) was a commercial Imperial enterprise, founded on 1 September 1664 to compete with the English (later British) and Dutch trading companies in the East Indies.

Company flag | |

| |

Native name | Compagnie française pour le commerce des Indes Orientales |

|---|---|

| Type | Public company |

| Industry | Trade |

| Fate | Dissolved and activities absorbed by the French Crown in 1769; reconstituted 1785, bankrupt 1794 |

| Founded | 1 September 1664 |

| Founder | Jean-Baptiste Colbert |

| Headquarters | Lorient |

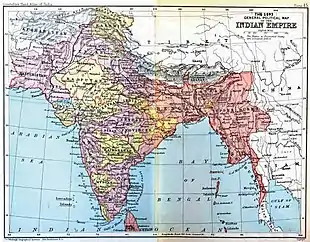

Imperial entities of India | |

| Dutch India | 1605–1825 |

|---|---|

| Danish India | 1620–1869 |

| French India | 1668–1954 |

| Casa da Índia | 1434–1833 |

| Portuguese East India Company | 1628–1633 |

| East India Company | 1612–1757 |

| Company rule in India | 1757–1858 |

| British Raj | 1858–1947 |

| British rule in Burma | 1824–1948 |

| Princely states | 1721–1949 |

| Partition of India | 1947 |

Planned by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, it was chartered by King Louis XIV for the purpose of trading in the Eastern Hemisphere. It resulted from the fusion of three earlier companies, the 1660 Compagnie de Chine, the Compagnie d'Orient and Compagnie de Madagascar. The first Director General for the Company was François de la Faye, who was adjoined by two Directors belonging to the two most successful trading organizations at that time: François Caron, who had spent 30 years working for the Dutch East India Company, including more than 20 years in Japan,[1] and Marcara Avanchintz, an Armenian trader from Isfahan, Persia.[2]

History

French king Henry IV authorized the first Compagnie des Indes Orientales, granting the firm a 15-year monopoly of the Indies trade. This precursor to Colbert's later Compagnie des Indes Orientales, however, was not a joint-stock corporation, and was funded by the Crown.

The initial capital of the revamped Compagnie des Indes Orientales was 15 million livres, divided into shares of 1000 livres apiece. Louis XIV funded the first 3 million livres of investment, against which losses in the first 10 years were to be charged. The initial stock offering quickly sold out, as courtiers of Louis XIV recognized that it was in their interests to support the King's overseas initiative. The Compagnie des Indes Orientales was granted a 50-year monopoly on French trade in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, a region stretching from the Cape of Good Hope to the Straits of Magellan. The French monarch also granted the Company a concession in perpetuity for the island of Madagascar, as well as any other territories it could conquer.

The Company failed to found a successful colony on Madagascar, but was able to establish ports on the nearby islands of Bourbon and Île-de-France (today's Réunion and Mauritius). By 1719, it had established itself in India, but the firm was near bankruptcy. In the same year the Compagnie des Indes Orientales was combined under the direction of John Law with other French trading companies to form the Compagnie Perpétuelle des Indes. The reorganized corporation resumed its operating independence in 1723.

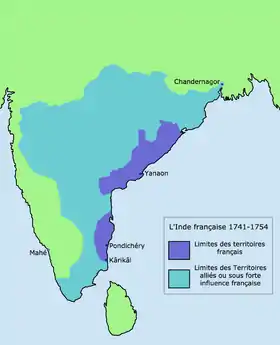

With the decline of the Mughal Empire, the French decided to intervene in Indian political affairs to protect their interests, notably by forging alliances with local rulers in south India. From 1741 the French under Joseph François Dupleix pursued an aggressive policy against both the Indians and the British until they ultimately were defeated by Robert Clive. Several Indian trading ports, including Pondichéry and Chandernagore, remained under French control until 1954.

The Company was not able to maintain itself financially, and it was abolished in 1769, about 20 years before the French Revolution. King Louis XVI issued a 1769 edict that required the Company to transfer to the state all its properties, assets and rights, which were valued at 30 million livres. The King agreed to pay all of the Company's debts and obligations, though holders of Company stock and notes received only an estimated 15 percent of the face value of their investments by the end of corporate liquidation in 1790.

The company was reconstituted in 1785[4] and issued 40,000 shares of stock, priced at 1,000 livres apiece. It was given monopoly on all trade with countries beyond the Cape of Good Hope[4] for an agreed period of seven years. The agreement, however, did not anticipate the French Revolution, and on 3 April 1790 the monopoly was abolished by an act of the new French Assembly which enthusiastically declared that the lucrative Far Eastern trade would henceforth be "thrown open to all Frenchmen".[4] The company, accustomed neither to competition nor official disfavor, fell into steady decline and was finally liquidated in 1794.

Map gallery

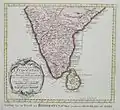

Carte de L'Indoustan. Bellin, 1770.

Carte de L'Indoustan. Bellin, 1770. French and other European settlements in India.

French and other European settlements in India. Acme of French influence 1741–1754.

Acme of French influence 1741–1754.

Liquidation scandal

Even as the company was headed consciously toward extinction, it became embroiled in its most infamous scandal. The Committee of Public Safety had banned all joint-stock companies on 24 August 1793, and specifically seized the assets and papers of the East India Company.[5] While its liquidation proceedings were being set up, directors of the company bribed various senior state officials to allow the company to carry out its own liquidation, rather than be supervised by the government.[5] When this became known the following year, the resulting scandal led to the execution of key Montagnard deputies like Fabre d'Églantine and Joseph Delaunay, among others.[5] The infighting sparked by the episode also brought down Georges Danton[6] and can be said to have led to the downfall of the Montagnards as a whole.[5]

Coins

French-issued copper coin, cast in Pondichéry for internal Indian trade.

French-issued copper coin, cast in Pondichéry for internal Indian trade.

French-issued rupee in the name of Mohammed Shah (1719-1748) for Northern India trade, cast in Pondichéry.

French-issued rupee in the name of Mohammed Shah (1719-1748) for Northern India trade, cast in Pondichéry.

See also

- British East India Company, founded in 1600

- Portuguese East India Company, founded 1628

- Carnatic Wars

- Chanda Sahib

- Dutch East India Company, founded in 1602

- Dutch West India Company, founded in 1621

- European chartered companies founded around the 17th century (in French)

- France-Asia relations

- French colonial empire

- French India

- List of trading companies

- Lorient

- Muzaffar Jang

- Salabat Jang

- Swedish East India Company, founded in 1731

- Whampoa anchorage

Notes

Further reading

- Ames, Glenn J. (1996). Colbert, Mercantilism, and the French Quest for Asian Trade. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-87580-207-9.

- Boucher, P. (1985). The Shaping of the French Colonial Empire: A Bio-Bibliography of the Careers of Richelieu, Fouquet and Colbert. New York: Garland.

- Doyle, William (1990). The Oxford History of the French Revolution (2 ed.). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925298-5.

- Greenwald, Erin M. (2016). Marc-Antoine Caillot and the Company of the Indies in Louisiana: Trade in the French Atlantic World. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807162859

- Lokke, C. L. (1932). France and the Colonial Question: A Study of Contemporary French Public Opinion, 1763-1801. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Malleson, G. B. (1893). History of the French in India. London: W.H. Allen & Co.

- Sen, S. P. (1958). The French in India, 1763-1816. Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay. ASIN B000HINRSC.

- Sen, S. P. (1947). The French in India: First Establishment and Struggle. Calcutta: University of Calcutta Press.

- Soboul, Albert (1975). The French Revolution 1787–1799. New York: Vintage. ISBN 0-394-71220-X. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- Subramanian, Lakshmi, ed. (1999). French East India Company and the Trade of the Indian Ocean: A Collection of Essays by Indrani Chatterjee. Delhi: Munshiram Publishers.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- McCabe, Ina Baghdiantz (2008). Orientalism in early Modern France. Berg. ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- Wellington, Donald C. French East India companies: A historical account and record of trade (Hamilton Books, 2006).

External links

- Museum of the French East India Company at Lorient

- The French East India Company (1785-1875) History of the last French East India Company on the site dedicated to its business lawyer Jean-Jacques Regis of Cambaceres.

- French East Indies Company nowadays