Khăn vấn

Khăn vấn (Nôm: 巾抆), khăn đóng (Nôm: 巾凍) or khăn xếp (Nôm: 巾插), is a kind of turban worn by Vietnamese people which had been popular since ancient time.

The word vấn means to wrap or coil around. The word khăn means scarf.

History

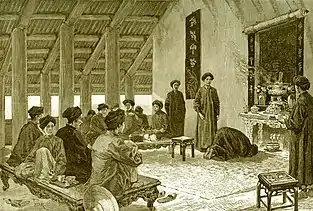

Turbans have historically been worn by peoples living in Southern China and Northern Vietnam since at least the Lý dynasty, with some depictions of Vietnamese commoners wearing them. They were historically worn by both the ethnic Kinh, as well as minorities such as the Tay, Hmong and Cham. For peasants and skilled workers, wrapping fabric around the head served as a way to beat the heat of tropical summers, especially in the South Central Coast. After the Trịnh-Nguyễn war, the residents in Quảng Nam (Canglan - the Southern) began to adapt to some customs of Champa, one of those was "vấn khăn" - wrap the scarf around head.[1]

_p333_CONCHIN_CHINESE%252C_SOLDIER.jpg.webp)

In 1744, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát of Đàng Trong (Huế) decreed that both men and women at his court wear trousers and a gown with buttons down the front. That the Nguyen Lords introduced ancient áo dài (áo ngũ thân). The members of the Đàng Trong court (southern court) were thus distinguished from the courtiers of the Trịnh Lords in Đàng Ngoài (Hanoi),[2][3] who wore áo giao lĩnh with long skirts and loose long hair. Hence, wrapping scarf around head became a unique custom in the south then. From 1830, Minh Mạng emperor force every civilian in the country to change their clothes, that custom became popular in the whole Vietnam.

Characteristics

Khăn vấn is a textile rectangle long and quite thick, coiled around the head. According to the decrees of Nguyễn dynasty written in the Historical chronicle of Đại Nam, the Vietnamese initially remained faithful to the Champa style, but gradually renovated to suit each period of time and for each social class.

In addition, according to the law of Nguyễn Dynasty, the problem of being too short and thin was prohibited, but too long and thick was also criticized as ugly.

Types

There are many types of khăn vấn, but they are basically classified into three types:

Khăn vấn for males

Khăn vấn for men, handy and casual. Use a thick or thin cloth (as you like to fix your bun) and wrap it 1-2 times around your head for a neat fit, except for yellow (that only emperor can wear), all other colors are allowed.

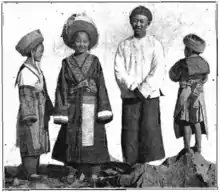

Ba Biêu, a Đề Thám's lieutenant. He is wearing khăn vấn chữ nhân (人 shaped) with 7 turns of coil.

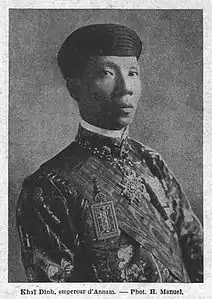

Ba Biêu, a Đề Thám's lieutenant. He is wearing khăn vấn chữ nhân (人 shaped) with 7 turns of coil. Khải Định was wearing khăn vấn chữ nhất (一 shaped) with 7 turns of coil.

Khải Định was wearing khăn vấn chữ nhất (一 shaped) with 7 turns of coil.

There are 2 most popular styles to wear khăn vấn for male: shaped chữ nhân (look like 人) and chữ nhất (look like 一).

- Chữ nhân style: the pleats on the forehead look like the word "nhân" (人 shaped)

- Chữ nhất style: the pleats on the forehead like the word "nhất" (一 shaped)

Khăn vấn for females

Khăn vấn for women and girl, also called rí or khăn lương, only worn by women. Handy and casual. A piece of cloth that is not too long, with padded hair inside, is wrapped around the head to keep hair neat. Young women when going to the festival also prefer to have ponytail for increased charm. Except for yellow (for royal family members) and pink (for singers and prostitutes), other colors are popular.

Nam Phương empress on stamp, published in 1950s. She was wearing khăn lương in Huế style.

Nam Phương empress on stamp, published in 1950s. She was wearing khăn lương in Huế style. A Tonkin woman was wearing khăn vấn in Northern style.

A Tonkin woman was wearing khăn vấn in Northern style. A Tonkin woman with black-painted teeth wearing khăn vấn in Northern style.

A Tonkin woman with black-painted teeth wearing khăn vấn in Northern style.

The way to wearing khăn vành in the Imperial City of Huế is different from the way to wear khăn vấn of Đàng Ngoài. Huế khăn vành is worn with the edge of the khăn vành facing upwards inside the ring. The second ring is attached to the outside of the first, rather than under the ring like in the North.[4][5]

Khăn vành dây (formal for females)

An formal style of khăn vấn for female is khăn vành dây or mũ mấn: Used on formal occasions. The very long, thick cloth was wrapped around the head like a funnel. The traditional khăn vành dây is recorded in dark blue color. Only on the most important occasions did one see a yellow khăn vành dây in the inner of Imperial City of Huế. In addition, from the empress mother, the empress to the princesses also only wore the dark blue khăn vành dây.[5]

Princess Mỹ Lương was wearing dark blue khăn vành dây with red nhật bình dress.

Princess Mỹ Lương was wearing dark blue khăn vành dây with red nhật bình dress. Nam Phương empress was wearing khăn vành dây with nhật bình dress.

Nam Phương empress was wearing khăn vành dây with nhật bình dress. Nam Phương empress was wearing yellow khăn vành dây with nhật bình dress.

Nam Phương empress was wearing yellow khăn vành dây with nhật bình dress.

In the old days inner Imperial City of Huế, phấn nụ (face powder made from flower mirabilis jalapa) and khăn vành went together. They use the nhiễu cát textile or Crêpe de Chine in the later period to cover their hair. The nhiễu cát textile was woven by Japanese in the past was only half as thin as the Crêpe de Chine, which was used in the Imperial City at the end of Nguyễn dynasty.[4] The ladies in Hue Palace often wore khăn vành dây on the ceremonies. A khăn vành dây made of the imported textile crêpe de Chine is 30 cm wide, has the average length is 13 m. A khăn vành dây made of Vietnamese nhiễu cát textile is nearly double longer.[5]

From the original width of 30cm, the khăn vành dây is folded into a width of 6 cm with the open edge turn upward. After that, it is wrapped around head in the shape chữ nhân, which means the pleats on the forehead look like the word "nhân" (人 shaped), look like letter "V" upside down, covering the shoulder hair and folds the scarf inside. When the scarf has wrapped around, fold the scarf half the width, starting from the nape, leaving the open edge facing up and then continuing. The khăn vành is tightly wrapped around head and forms a large dish shape. Because of nhiễu cát textile has high elasticity and roughness, the khăn vành rarely slips. The end of the scarf is cleverly tucked into the back of the scarf, but sometimes the women use pins for convenience.[5]

Variants

In the Mekong Delta region, there is a popular variant called khăn rằn, which combines the traditional khăn vấn of Vietnamese with the kerchief of the Khmer. But unlike the red color of the Khmer, Vietnamese towels are black and white. Towels usually 1m2 long, size 40–50 cm. Because it is only popular in the South, it is temporarily considered a characteristic of this place.

In the 21st century, even more types of fake khăn vấn, mũ mấn were created, such as the mũ mấn made of wooden, plastic, and metal. However, those were often criticized by the press as harsh and even disgusting. Therefore, the problem of neat and beautiful towels is considered a general trend to evaluate the quality of each person.

See also

References

- Trần, Quang Đức (2013). Ngàn năm áo mũ. Vietnam: Công Ty Văn Hóa và Truyền Thông Nhã Nam. ISBN 978-1629883700.

- Tran, My-Van (2005). A Vietnamese Royal Exile in Japan: Prince Cuong De (1882-1951). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415297165.

- Dutton, George; Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0231138635.

- Trịnh, Bách (2004). "Trang điểm cung đình" (pdf). Tạp chí Nghiên cứu và Phát triển (in Vietnamese). 1 (44): 36.

- Trịnh, Bách (2004). "Trang điểm cung đình" (pdf). Tạp chí Nghiên cứu và Phát triển (in Vietnamese). 1 (44): 37.