Mekong Delta

The Mekong Delta (Vietnamese: Đồng bằng Sông Cửu Long, literally Nine Dragon river delta or simply Vietnamese: Đồng Bằng Sông Mê Kông, "Mekong river delta"), also known as the Western Region (Vietnamese: Miền Tây) or the South-western region (Vietnamese: Tây Nam Bộ) is the region in southwestern Vietnam where the Mekong River approaches and empties into the sea through a network of distributaries. The Mekong delta region encompasses a large portion of southwestern Vietnam of over 40,500 square kilometres (15,600 sq mi).[2] The size of the area covered by water depends on the season. Before 1975, Mekong Delta was part of the Republic of Vietnam.

Mekong Delta

Đồng bằng Sông Cửu Long Đồng Bằng Sông Mê Kông | |

|---|---|

Rice paddy in the Mekong Delta. | |

| Nickname(s): "Nine Dragon river delta", "The West" | |

Provincial map | |

| Coordinates: 10°02′N 105°47′E | |

| Country | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 40,576.6 km2 (15,666.7 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • Total | 21,492,987 |

| • Density | 530/km2 (1,400/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+07:00 (ICT) |

Today, the region comprises 12 provinces: Long An, Đồng Tháp, Tiền Giang, An Giang, Bến Tre, Vĩnh Long, Trà Vinh, Hậu Giang, Kiên Giang, Sóc Trăng, Bạc Liêu, and Cà Mau, along with the province-level municipality of Cần Thơ.

The Mekong Delta has been dubbed a 'biological treasure trove'. Over 1,000 animal species were recorded between 1997 and 2007 and new species of plants, fish, lizards, and mammals have been discovered in previously unexplored areas, including the Laotian rock rat, thought to be extinct.[3]

History

Funan and Chenla period

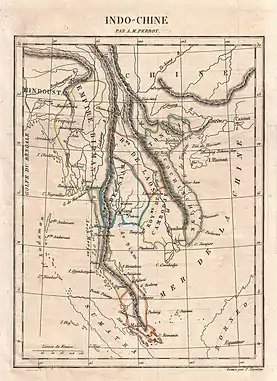

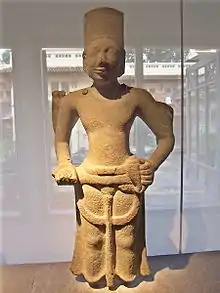

The Mekong Delta was likely inhabited long since prehistory; the civilizations of Funan and Chenla maintained a presence in the Mekong Delta for centuries.[4] Archaeological discoveries at Óc Eo and other Funanese sites show that the area was an important part of the Funan civilization, bustling with trading ports and canals as early as in the first century AD and extensive human settlement in the region may have gone back as far as the 4th century BC. Angkor Borei is a site in the Mekong Delta that existed between 400 BC-500 AD. This site had extensive maritime trade networks throughout Southeast Asia and with India, and is believed to have possibly been the ancient capital to the civilization of Funan.[5]

Cambodian period

Together with Southeast (Vietnam), the region was known as Kampuchea Krom (Lower Cambodia) to the Khmer Empire, which likely maintained settlements there centuries before its rise in the 11th and 12th centuries.[nb 1] The kingdom of Champa, though mainly based along the coast of modern Central Vietnam, is known to have expanded west into the Mekong Delta, seizing control of Prey Nokor (the precursor to modern-day Ho Chi Minh City) by the end of the 13th century.[nb 2] Author Nghia M. Vo suggests that a Cham presence may indeed have existed in the area prior to Khmer occupation.[nb 3] However, this does not take into account that Kampuchea Krom (including Prey Nokor) existed since early history or at least Funan (Salkin et al., 1996);[6] and the fact that between 10th-12th century, there were several clashes between Khmer Empire and Champa (mainly based along modern Central Vietnam).[7][6]

Beginning in the 1620s, Cambodian king Chey Chettha II (1618–1628) allowed the Vietnamese to settle in the area, and to set up a custom house at Prey Nokor, which they colloquially referred to as Sài Gòn.[8] The increasing waves of Vietnamese settlers which followed overwhelmed the kingdom—weakened as it was due to war with Thailand—and slowly Vietnamized the area. During the late 17th century, Mạc Cửu, a Chinese anti-Qing general, began to expand Vietnamese and Chinese settlements deeper into Cambodian lands, and in 1691, a small Vietnamese outpost was established in Prey Nokor(Ho Chi Minh city). The Mekong Delta became a territorial dispute between Cambodian and Vietnamese in the succeeding centuries. In 1757, Vietnamese lords had acquire control of Cà Mau. By the 1860's, French colonists had established control over the Mekong Delta and established the colony of French Cochinchina.

Vietnamese period

In 1698, the Nguyễn lords of Huế sent Nguyễn Hữu Cảnh, a Vietnamese noble, to the area to establish Vietnamese administrative structures in the area.[9] During the Tây Sơn wars and the subsequent Nguyễn Dynasty, Vietnam's boundaries were pushed as far as the Cape Cà Mau. In 1802 Nguyễn Ánh crowned himself emperor Gia Long and unified all the territories comprising modern Vietnam, including the Mekong Delta.

Upon the conclusion of the Cochinchina Campaign in the 1860s, the area became part of Cochinchina, France's first colony in Vietnam, and later, part of French Indochina.[10] Beginning during the French colonial period, the French patrolled and fought on the waterways of the Mekong Delta region with their Divisions navales d'assaut (Dinassaut), a tactic which lasted throughout the First Indochina War, and was later employed by the US Navy Mobile Riverine Force.[11] During the Vietnam War—also referred to as the Second Indochina War—the Delta region saw savage fighting between Viet Cong (NLF) guerrillas and the US 9th Infantry Division and units of the United States Navy's swift boats and hovercraft (PACVs) plus the Army of the Republic of Vietnam 7th, 9th, and 21st Infantry Divisions. As a military region the Mekong Delta was encompassed by the IV Corps Tactical Zone (IV CTZ).

In 1975, North Vietnamese soldiers and Viet Cong soldiers launched a massive invasion in many parts of South Vietnam. While I, II, and III Corps collapsed significantly, IV Corps was still highly intact due to under Major General Nguyen Khoa Nam overseeing strong military operations to prevent VC taking over any important regional districts. Brigadier General Le Van Hung, the head of 21st Division commander, stayed office in Can Tho to continue defending successfully against VC. When the South Vietnamese President Duong Van Minh ordered a surrender, both ARVN generals in Can Tho, General Le Van Hung and Nguyen Khoa Nam, committed suicide after deciding not to continue battle against the VC soldiers similar as siege of An Loc. In Binh Thuy Air Base, where the ARVN soldiers and number of aircraft defend on military operations, some ARVN soldiers and air base personnel who defended long-time at air base evacuated by helicopters to depart to presumably at Thailand shortly after hearing President Minh surrendered. Several jet fighters were flown out to Thailand from still-unoccupied Binh Thuy AB. Within hours after RVN ceased to exist, VC soldiers occupied Binh Thuy Air Base and captured number of ARVN soldiers and AB personnel who didn't escape by air or surrounded all around enemy VC soldiers.[12] In My Tho, Brigadier General Tran Van Hai, who was in charged protecting National Highway 4 (now NH1A) from Saigon to Can Tho, committed suicide when President Minh ordered ARVN forces to surrendered. General Tran Van Hai is one of the three ARVN generals refused to be evacuated by American when the North Vietnamese soldiers invade Saigon.[13] Several ARVN soldiers continued to fight resistance against VC in several places including few intact provincial capitals shortly after Minh's surrender that later either surrendered or disbanded at night or at least next day when remaining ARVN soldiers exhausted from counterattack.[14]

In the late 1970s, the Khmer Rouge regime attacked Vietnam in an attempt to reconquer the Delta region. This campaign precipitated the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia and subsequent downfall of the Khmer Rouge.

Geography

The Mekong Delta, as a region, lies immediately to the west of Ho Chi Minh City (also called Saigon by locals), roughly forming a triangle stretching from Mỹ Tho in the east to Châu Đốc and Hà Tiên in the northwest, down to Cà Mau at the southernmost tip of Vietnam, and including the island of Phú Quốc.

The Mekong Delta region of Vietnam displays a variety of physical landscapes, but is dominated by flat flood plains in the south, with a few hills in the north and west. This diversity of terrain was largely the product of tectonic uplift and folding brought about by the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates about 50 million years ago. The soil of the lower Delta consists mainly of sediment from the Mekong and its tributaries, deposited over thousands of years as the river changed its course due to the flatness of the low-lying terrain.[15]

The present Mekong Delta system has two major distributary channels, both discharging directly into the East Sea. The Holocene history of the Mekong Delta shows delta progradation of about 200 km during the last 6 kyr. During the Middle Holocene the Mekong River was discharging waters into both the East Sea and the Gulf of Thailand.[16] The water entering the Gulf of Thailand was flowing via a palaeochannel located within the western part of the delta; north of the Camau Peninsula.[17] Upper Pleistocene prodeltaic and delta front sediments interpreted as the deposits of the palaeo-Mekong River were reported from central basin of the Gulf of Thailand[18][19]

The Mekong Delta is the region with the smallest forest area in Vietnam. 300,000 hectares (740,000 acres) or 7.7% of the total area are forested as of 2011. The only provinces with large forests are Cà Mau Province and Kiên Giang Province, together accounting for two-thirds of the region's forest area, while forests cover less than 5% of the area of all of the other eight provinces and cities.[20]

Coastal erosion

| Shoreline change (m/yr) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zones | 1973–1979 | 1973–1979 | 1987–1995 | 1987–1995 | 1987–1995 | 43-yr average |

| Zone-1 | 8.66 | 8.07 | 12.07 | 9.68 | 4.52 | 8.87 |

| Zone-2 | −10.32 | −8.00 | −12.22 | −13.15 | −20.9 | −12.79 |

| Zone-3 | 28.15 | 23.33 | 27.55 | 19.48 | 11.83 | 21.53 |

| Zone-4 | 8.43 | 2.48 | 3.57 | -10.03 | −4.53 | −1.66 |

| All areas | 7.77 | 6.11 | 7.84 | 2.75 | −1.42 | 4.36 |

| Area change (km2/yr) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zones | 1973–1979 | 1973–1979 | 1987–1995 | 1987–1995 | 1987–1995 | 43-yr average |

| Zone-1 | 1.94 | 2.01 | 2.96 | 2.25 | 1.15 | 2.12 |

| Zone-2 | −1.39 | −1.87 | −2.23 | −1.75 | −1.71 | −1.71 |

| Zone-3 | 2.82 | 2.16 | 1.71 | 1.09 | 1.64 | 1.99 |

| Zone-4 | 0.95 | 0.35 | −0.53 | −0.56 | −1.13 | −0.18 |

| All areas | 4.32 | 2.64 | 1.91 | 1.03 | −0.05 | 2.23 |

From 1973 to 2005, the Mekong Delta's seaward shoreline growth decreased gradually from a mean of 7.8 m/yr to 2.8 m/yr, and after 2005 it became negative, with a retreat rate of −1.4 m/yr. The net deltaic land area gain has also been slowing, with the mean rate decreasing from 4.3 km2/yr (1973–1979) to 1.0 km2 yr (1995–2005), and then to −0.05 km2/yr (2005–2015). Thus, in about 2005, the subaerial Mekong Delta transitioned from a constructive mode to an erosional (or destructive) mode.[21][22]

Climate change concerns

Being a low-lying coastal region, the Mekong Delta is particularly susceptible to floods resulting from rises in sea level due to climate change.[23] The Climate Change Research Institute at Cần Thơ University, in studying the possible consequences of climate change, has predicted that, besides suffering from drought brought on by seasonal decrease in rainfall, many provinces in the Mekong Delta will be flooded by the year 2030. The most serious cases are predicted to be the provinces of Bến Tre and Long An, of which 51% and 49%, respectively, are expected to be flooded if sea level rise by 1 metre (3 ft 3 in).[24] Another problem caused by climate change is the increasing soil salinity near the coasts. Bến Tre Province is planning to reforest coastal regions to counter this trend.[25] The duration of inundation at an important road in the city of Can Tho is expected to continue to rise from the current total of 72 inundated days per year to 270 days by 2030 and 365 days by 2050. This is attributed to the combined influence of sea-level rise and land subsidence,[26] which occurs at about 1.1 centimetres (0.43 in) annually.[27] Several projects and initiatives on local, regional and state levels work to counter this trend and save the Mekong Delta. One programme for integrated coastal management, for instance, is supported by Germany and Australia.[28]

In August 2019, a Nature Communications study using an improved measure of elevation estimation, found that the delta was much lower than previous estimates, only a mean 0.82 metres (2 ft 8 in) above sea level, with 75% of the delta—an area where 12 million people currently live—falling below 1 metre (3 ft 3 in).[27] It is expected that a majority of the delta will be below sea level by 2050.[29]

Demographics

The inhabitants of the Mekong Delta region are predominantly ethnic Viet. The region, formerly part of the Khmer Empire, is also home to the largest population of Khmers outside of the modern borders of Cambodia. The Khmer minority population live primarily in the Trà Vinh, Sóc Trăng, and Muslim Chăm in Tan Chau, An Giang provinces. There are also sizeable Hoa (ethnic Chinese) populations in the Kiên Giang, and Trà Vinh provinces. The region had a population of 17.33 million people in 2011.[20]

The population of the Mekong Delta has been growing relatively slowly in recent years, mainly due to out-migration. The region's population only increased by 471,600 people between 2005 and 2011, while 166,400 people migrated out in 2011 alone. Together with the central coast regions, it has one of the slowest growing populations in country. Population growth rates have been between 0.3% and 0.5% between 2008 and 2011, while they have been over 2% in the neighbouring southeastern region.[20] Net migration has been negative in all of these years. The region also has a relatively low fertility rate, at 1.8 children per woman in 2010 and 2011, down from 2.0 in 2005.[20]

Provinces

| Province- Level Division |

Capital | Area | Population (2019) |

Population density | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (km2) | (mile²) | (persons/km2) | (persons/mile²) | |||

| An Giang | Long Xuyên | 3,536.8 | 1,365.6 | 2,412,569 | 625.0 | 1,619 |

| Bạc Liêu | Bạc Liêu | 2,584.1 | 997.7 | 978,695 | 317.4 | 822 |

| Bến Tre | Bến Tre | 2,360.2 | 911.3 | 1,624,471 | 573.4 | 1,485 |

| Cà Mau | Cà Mau | 5,331.7 | 2,058.6 | 1,421,200 | 231.1 | 599 |

| Đồng Tháp | Cao Lãnh | 3,376.4 | 1,303.6 | 2,476,940 | 494.0 | 1,279 |

| Hậu Giang | Vị Thanh | 1,601.1 | 618.2 | 974,126 | 497.7 | 1,289 |

| Kiên Giang | Rạch Giá | 6,348.3 | 2,451.1 | 2,044,153 | 265.4 | 687 |

| Long An | Tân An | 4,493.8 | 1,735.1 | 1,940,596 | 316.7 | 820 |

| Sóc Trăng | Sóc Trăng | 3,312.3 | 1,278.9 | 1,620,750 | 385.3 | 998 |

| Tiền Giang | Mỹ Tho | 2,484.2 | 959.2 | 2,002,767 | 691.3 | 1,790 |

| Trà Vinh | Trà Vinh | 2,295.1 | 886.1 | 1,285,842 | 451.7 | 1,170 |

| Vĩnh Long | Vĩnh Long | 1,479.1 | 571.1 | 1,141,677 | 714.6 | 1,851 |

| Cần Thơ (municipality) | 1,401.6 | 541.2 | 1,569,301 | 813.3 | 2,106 | |

Economy

The Mekong Delta is by far Vietnam's most productive region in agriculture and aquaculture, while its role in industry and foreign direct investment is much smaller.

Agriculture

2.6 million ha in the Mekong Delta are used for agriculture, which is one fourth of Vietnam's total.[20] Due to its mostly flat terrain and few forested areas (except for Cà Mau Province), almost two-thirds (64.5%) of the region's land can be used for agriculture. The share of agricultural land exceeds 80% in Cần Thơ and neighbouring Hậu Giang Province and is below 50% only in Cà Mau Province (32%) and Bạc Liêu Province (42%).[20] The region's land used for growing cereals makes up 47% of the national total, more than northern and central Vietnam combined. Most of this is used for rice cultivation.

Rice output in 2011 was 23,186,000t, 54.8% of Vietnam's total output. The strongest producers are Kiên Giang Province, An Giang Province, and Đồng Tháp Province, producing over 3 million tonnes each and almost 11 million tonnes together. Any two of these provinces produce more than the entire Red River Delta.[20] Only three provinces produce less than 1 million tonnes of rice (Bạc Liêu Province, Cà Mau Province, Bến Tre Province).[20]

Fishery

The Mekong Delta is also Vietnam's most important fishing region. It has almost half of Vietnam's capacity of offshore fishing vessels (mostly in Kien Gian with almost 1/4, Bến Tre, Cà Mau, Tiền Giang, Bạc Liêu). Fishery output was at 3.168 million tons (58.3% of Vietnam) and has experienced rapid growth from 1.84mt in 2005.[20] All of Vietnam's largest fishery producers with over 300kt of output are in the Mekong Delta: Kiên Giang, Cà Mau, Đồng Tháp, An Giang, and Bến Tre.[20]

Despite the region's large offshore fishing fleet, 2/3 (2.13 million tonnes out of Vietnam's total of 2.93) of fishery output actually comes from aquaculture.[20]

December 2015, aquaculture production was estimated at 357 thousand tons, up 11% compared to the same period last year, bringing the total aquaculture production 3516 thousand tons in 2015, up 3.0% compared to the same period. Although aquaculture production has increased overall, aquaculture still faces many difficulties coming from export markets.[30]

Industry and FDI

The Mekong Delta is not strongly industrialized, but is still the third out of seven regions in terms of industrial gross output. The region's industry accounts for 10% of Vietnam's total as of 2011.[20] Almost half of the region's industrial production is concentrated in Cần Thơ, Long An Province and Cà Mau Province. Cần Thơ is the economic center of the region and more industrialized than the other provinces. Long An has been the only province of the region to attract part of the manufacturing booming around Ho Chi Minh City and is seen by other provinces as an example of successful FDI attraction.[31] Cà Mau Province is home to a large industrial zone including power plants and a fertiliser factory.[32]

Accumulated foreign direct investment in the Mekong Delta until 2011 was $10.257bn.[20] It has been highly concentrated in a few provinces, led by Long An and Kiên Giang with over $3bn each, Tiền Giang and Cần Thơ (around 850m), Cà Mau (780m) and Hậu Giang (673m), while the other provinces have received less than 200m each.[20] In general, the performance of the region in attracting FDI is evaluated as unsatisfactory by local analysts and policymakers.[31] Companies from Ho Chi Minh City have also invested heavily in the region. Their investment from 2000 to June 2011 accounted for 199 trillion VND (almost $10bn).[33]

Infrastructure

The construction of the Cần Thơ Bridge, a cable-stayed bridge over the largest distributary of the Mekong River, was completed on April 12, 2010, three years after a collapse that killed 54 and injured nearly 100 workers. The bridge replaces the ferry system that currently runs along National Route 1A, and links Vĩnh Long Province and Cần Thơ city. The cost of construction is estimated to be 4.842 trillion Vietnamese đồng (approximately 342.6 million United States dollars), making it the most expensive bridge in Vietnam.[34]

Culture

Life in the Mekong Delta revolves much around the river, and many of the villages are often accessible by rivers and canals rather than by road.

The region is home to cải lương, a form of Kinh/Vietnamese folk opera. Cai Luong Singing appeared in Mekong Delta in the early 20th century. Cai Luong Singing is often performed in the soundtrack of guitar and zither. Cai Luong is a kind of play telling a story. A sort of play often includes two main parts: the dialogue part and the singing part to express their thoughts and emotions.[35]

Literature and movies

Nguyễn Ngọc Tư, an author from Cà Mau Province, has written many popular books about life in the Mekong Delta such as:

- Ngọn đèn không tắt (The Inextinguishable Light, 2000)

- Ông ngoại (Grandpa, 2001)

- Biển người mênh mông (The Ocean of People, 2003)

- Giao thừa (New Year's Eve, 2003)

- Nước chảy mây trôi (Flowing Waters, Flying Clouds, 2004)

- Cánh đồng bất tận (The Endless Field, 2005)

The 2004 film The Buffalo Boy is set in Cà Mau Province.

In The Simpsons, Principal Skinner was on recon in the steaming Mekong Delta in 1968. He was captured, and lived in a POW camp for 3 years, forced to subsist on a thin stew made of fish, vegetables, prawns, coconut milk, and four kinds of rice.

See also

Notes

- "At the height of the Khmer Empire's economic and political strength, during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, its rulers established and fostered the growth of Prey Nokor[...] It is possible that there already had been a settlement at this location in the Mekong marshes for some centuries, depending, as Prey Nokor did, on the handling of goods traded between the countries bordering the South China Sea and the interior provinces of the empire." Robert M. Salkin; Trudy Ring (1996). Paul E. Schellinger; Robert M. Salkin (eds.). Asia and Oceania. International Dictionary of Historic Places. 5. Taylor & Francis. p. 353. ISBN 1-884964-04-4.

- "Such a trading center was bound to be one of the prizes in the struggle for power that developed in the thirteenth century between the declining Khmer Empire and the expanding kingdom of Champa, and by the end of that century the Cham people had seized control of the town." Robert M. Salkin; Trudy Ring (1996). Paul E. Schellinger; Robert M. Salkin (eds.). Asia and Oceania. International Dictionary of Historic Places. 5. Taylor & Francis. p. 353. ISBN 1-884964-04-4.

- "Saigon began as the Cham village of Baigaur, then became the Khmer Prey Nokor before being taken over by the Vietnamese and renamed Gia Dinh Thanh and then Saigon." Nghia M. Vo (2009). The Viet Kieu in America: Personal Accounts of Postwar Immigrants from Vietnam. McFarland & Co. p. 218. ISBN 9780786454907.

References

- Statistical Handbook of Vietnam 2014 Archived July 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, General Statistics Office of Vietnam

- Mekong Delta Archived September 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine on ARCBC (ASEAN Regional Centre for Biodiversity Conservation) site

- Ashley Fantz, "Mekong a 'treasure trove' of 1,000 newly discovered species", CNN. December 16, 2008.

- Robert M. Salkin; Trudy Ring (1996). Paul E. Schellinger; Robert M. Salkin (eds.). Asia and Oceania. International Dictionary of Historic Places. 5. Taylor & Francis. p. 353. ISBN 1-884964-04-4.

- Stark, M.; Sovath, B. (2001). "Recent research on emergent complexity in Cambodia's Mekong". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 21 (5): 85–98.

- Robert M. Salkin; Trudy Ring (1996). Paul E. Schellinger; Robert M. Salkin (eds.). Asia and Oceania. International Dictionary of Historic Places. 5. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-884964-04-4.

- Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- Nghia M. Vo; Chat V. Dang; Hien V. Ho (August 29, 2008). The Women of Vietnam. Saigon Arts, Culture & Education Institute Forum. Outskirts Press. ISBN 978-1-4327-2208-1.

- The first settlers, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved September 25, 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Robert M. Salkin; Trudy Ring (1996). Paul E. Schellinger; Robert M. Salkin (eds.). Asia and Oceania. International Dictionary of Historic Places. 5. Taylor & Francis. p. 354. ISBN 1-884964-04-4.

- Leulliot, Nowfel. "Dinassaut : Riverine warfare in Indochina, 1945–1954".

- https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-04-30-mn-174-story.html

- Elliott, David (2003). The Vietnamese War: Revolution and Social Change in the Mekong ..., Volume 1. New York. pp. 1376–1377. ISBN 9781315698809.

- "Holdouts". War Never Dies. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- "Physical and Geographical Features". Mekong River Awareness Kit. Convention on Biological Diversity. Archived from the original on August 8, 2009. Retrieved June 18, 2010.

|section=ignored (help) - Liu, J. P.; DeMaster, D. J.; Nittrouer, C. A.; Eidam, E. F.; Nguyen, T. T. (2017). "A seismic study of the Mekong subaqueous delta: Proximal versus distal sediment accumulation". Cont. Shelf Res. 147: 197–212. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2017.07.009.

- Ta, T. K. O.; Nguyen, V. L.; Tateishi, M.; Kobayashi, I.; Tanabe, S.; Saito, Y. (2002). "Holocene delta evolution and sediment discharge of the Mekong River, southern Vietnam". Quaternary Science Reviews. 21: 1807–1819. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(02)00007-0.

- Puchala, R. (2014). Morphology and origin of modern seabed features in the central basin of the Gulf of Thailand (PhD thesis). doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3891.0808.

- Xue, Zuo; Liu, J. Paul; Demaster, Dave; Van Nguyen, Lap; Ta, Thi Kim Oanh (2010). "Late Holocene Evolution of the Mekong Subaqueous Delta, Southern Vietnam". Marine Geology. 269 (1–2): 46–60. Bibcode:2010MGeol.269...46X. doi:10.1016/J.Margeo.2009.12.005.

- General Statistics Office (2012): Statistical Yearbook of Vietnam 2011. Statistical Publishing House, Hanoi

- Liu, J. P.; DeMaster, D. J.; Nguyen, T. T.; Saito, Y.; Nguyen, V. L.; Ta, T. K. O.; Li, X. (2017). "Stratigraphic formation of the Mekong River Delta and its recent shoreline changes". Oceanography. 30 (3): 72–83. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2017.316.

- Li, X.; Liu, J. P.; Saito, Y.; Nguyen, V. L. (2017). "Recent evolution of the Mekong Delta and the impact of dams". Earth Science Review. 175: 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.10.008.

- "Report: Flooded Future: Global vulnerability to sea level rise worse than previously understood". climatecentral.org. October 29, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- "Mekong Delta: more flood and drought". VietnamNet Bridge. March 19, 2009.

- "Xây dựng rừng phòng hộ để thích ứng với biến đổi khí hậu". Saigon Times. June 6, 2011. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- "Sea-Level Rise and Land Subsidence: Impacts on Flood Projections for the Mekong Delta's Largest City". MDPI. September 21, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- Minderhoud, P. S. J.; Coumou, L.; Erkens, G.; Middelkoop, H.; Stouthamer, E. (2019). "Mekong delta much lower than previously assumed in sea-level rise impact assessments". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 3847. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.3847M. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-11602-1. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6713785. PMID 31462638.

- Severin Peters, Christian Henckes (March 18, 2017). "Saving the Mekong Delta". D+C, development and cooperation. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- Lu, Denise; Flavelle, Christopher (October 29, 2019). "Rising Seas Will Erase More Cities by 2050, New Research Shows". The New York Times. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- "Mekong Delta Tours – Official MeKong delta Travel".

- "Nâng nội lực, hút vốn FDI vào ĐBSCL". Saigon Times. December 7, 2012. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- "Gas, fertiliser industrial zone opens in Ca Mau". Viet Nam News. October 27, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- "TPHCM đã đầu tư vào ĐBSCL gần 199.000 tỉ đồng". Saigon Times. July 25, 2011. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- "SE Asia's longest cable-stayed bridge underway in Can Tho". September 28, 2004. Archived from the original on September 1, 2007. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

- "Cai Luong - The Traditional Music Of The Mekong Delta". Retrieved October 2, 2019.

Further reading

- Renaud, F. G. and C. Kuenzer (2012): The Mekong Delta System. Interdisciplinary Analyses of a River Delta (= Springer Environmental Science and Engineering). Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-3961-1.

- Kuenzer, C. and F. G. Renaud (2012): Climate Change and Environmental Change in River Deltas Globally. In: Renaud, F. G. and C. Kuenzer (eds.): The Mekong Delta System. Interdisciplinary Analyses of a River Delta (= Springer Environmental Science and Engineering). Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 7–48.

- Renaud F. G. and C. Kuenzer (2012): Introduction. In: Renaud, F. G. and C. Kuenzer (eds.): The Mekong Delta System. Interdisciplinary Analyses of a River Delta (= Springer Environmental Science and Engineering). Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 3–6.

- Moder, F., C. Kuenzer, Z. Xu, P. Leinenkugel and Q. Bui Van (2012): IWRM for the Mekong Basin. In: Renaud, F. G. and C. Kuenzer (eds.): The Mekong Delta System. Interdisciplinary Analyses of a River Delta (= Springer Environmental Science and Engineering). Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 133–166.

- Klinger, V., G. Wehrmann, G. Gebhardt and C. Kuenzer (2012): A Water related Web-based Information System for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong Delta. In: Renaud, F. G. and C. Kuenzer (eds.): The Mekong Delta System. Interdisciplinary Analyses of a River Delta (= Springer Environmental Science and Engineering). Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 423–444.

- Gebhardt, S., L. D. Nguyen and C. Kuenzer (2012): Mangrove Ecosystems in the Mekong Delta. Overcoming Uncertainties in Inventory Mapping Using Satellite Remote Sensing Data. In: Renaud, F. G. and C. Kuenzer (eds.): The Mekong Delta System. Interdisciplinary Analyses of a River Delta (= Springer Environmental Science and Engineering). Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 315–330.

- Kuenzer, C., H. Guo, J. Huth, P. Leinenkugel, X. Li and S. Dech (2013): Flood Mapping and Flood Dynamics of the Mekong Delta. ENVISAT-ASAR-WSM Based Time-Series Analyses. In: Remote Sensing 5, pp. 687–715. DOI: 10.3390/rs5020687.

- Gebhardt, S., J. Huth, N. Lam Dao, A. Roth and C. Kuenzer (2012): A comparison of TerraSAR-X Quadpol backscattering with RapidEye multispectral vegetation indices over rice fields in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. In: International Journal of Remote Sensing 33 (24), pp. 7644–7661.

- Leinenkugel, P., T. Esch and C. Kuenzer (2011): Settlement detection and impervious surface estimation in the Mekong Delta using optical and SAR remote sensing data. In: Remote Sensing of Environment 115 (12), pp. 3007–3019.

- Kuenzer, C., I. Klein, T. Ullmann, E. Foufoula-Georgiou, R. Baumhauer and S. Dech (2015): Remote Sensing of River Delta Inundation: Exploiting the Potential of Coarse Spatial Resolution, Temporally-Dense MODIS Time Series. In: Remote Sensing 7, pp. 8516-8542. DOI: 10.3390/rs70708516.

- Kuenzer, C., H. Guo, I. Schlegel, V. Tuan, X. Li and S. Dech (2013): Varying scale and capability of envisat ASAR-WSM, TerraSAR-X scansar and TerraSAR-X Stripmap data to assess urban flood situations: A case study of the mekong delta in Can Tho province. In: Remote Sensing 5 (10), pp. 5122-5142. DOI: 10.3390/rs5105122.

External links

- The WISDOM Project, a Water related Information System for the Mekong Delta

- Image Google map of the Mekong Delta.

- Fruits found at Mekong Delta

- Climate change

- Mekong Delta Climate Change Forum 2009 Documents. International Centre for Environmental Management.

- Release of arsenic to deep groundwater in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam, linked to pumping-induced land subsidence.

%252C_Malaysia%252C_Sumatra%252C_Borneo_-_Geographicus_-_Siam-ottens-1710.jpg.webp)