King Edward VII's Hospital

King Edward VII's Hospital (formal name: King Edward VII's Hospital Sister Agnes) is a private hospital in Marylebone, in central London. It was established in 1899 at the suggestion of the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) who went on to become the hospital's patron. It was first located at 17 Grosvenor Crescent, the home of Agnes Keyser, a mistress of the Prince of Wales. It moved to Beaumont Street in 1948 where the current premises were opened by Queen Mary.

| King Edward VII's Hospital | |

|---|---|

King Edward VII's Hospital | |

| |

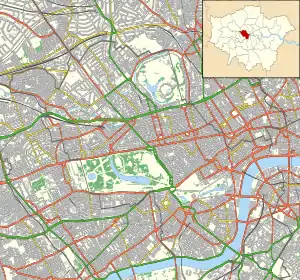

Location in Westminster | |

| Geography | |

| Location | London, W1 United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°31′15.3″N 0°9′1.5″W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | Private |

| Funding | Non-profit hospital |

| Type |

|

| Patron | Queen Elizabeth II |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | No |

| Beds | 56[2] |

| History | |

| Opened | 1899[3] |

| Links | |

| Website | Official website |

The hospital initially admitted sick and mostly gunshot wounded British Army officers who had returned from the Second Boer War and subsequently specialised in treating military patients such as the future prime minister Harold Macmillan who was treated there during the First World War. More recently it has also treated civilian patients, including members of the British royal family such as Queen Elizabeth II.

In December 2012, the hospital received international media attention when, while Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge was staying there, two DJs from the Australian radio station 2Day FM made a hoax telephone call to the hospital, pretending to be Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Charles. Soon after, nurse Jacintha Saldanha, who had passed on the hoax call to the other nurse in the Duchess's private ward, was found dead. The Metropolitan Police described it as an "unexplained death". The Guardian subsequently reported that it understood that the third of the notes left by Saldanha "addressed her employers, the hospital, and contained criticism of staff there."

Foundation

The hospital was established in 1899 at the suggestion of the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), the eldest son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.[4] It was first located at 17 Grosvenor Crescent, the home of Agnes Keyser, a mistress of the Prince, whom he had met the previous year at the home of Alice Keppel.[5][6] Keyser and her sister Fanny had inherited the house in Belgravia from their wealthy father, who was a member of the stock market.[4] At the instruction of the Prince, Keyser assumed the role of matron under the title "Sister" and became known as "Sister Agnes".[6] The hospital, based in the Keyser's home and with only 12 beds, a basic operating theatre and a staff of six nurses, admitted its first mostly gunshot wounded British Army officers who had returned from the Second Boer War in February 1900, a week after receiving a letter of gratitude from General Evelyn Wood VC.[4]

20th Century

Following the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, the Prince became King Edward VII and he subsequently became the hospital's first patron.[2][5] In 1904 the hospital was officially named King Edward VII's Hospital for Officers and continued to care for military officers during peacetime.[5] In 1904, eight years after retiring from the Indian Medical Service with the rank of honorary Colonel, Peter Freyer became a member of the honorary medical staff of the Hospital, and remained there until 1909,[7][8] the same year in which the Constitution of the hospital was modified.[9]

In 1914 the hospital had 16 beds.[1] During the First World War the young novelist Stuart Cloete was nursed at the hospital after being wounded at the Battle of the Somme.[10][11] In the same battle, the future British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, was also wounded and treated at the hospital, where he underwent a series of long operations followed by recuperation there from 1916–18.[12] In 1930, the hospital was awarded a Royal Charter "to operate an acute Hospital where serving and retired officers of the Services and their spouses can be treated at preferential rates."[13]

In 1941 the interior of the building was badly damaged by bombing, and Sister Agnes died shortly after.[6][14] In 1948 the hospital moved to Beaumont Street.[15] It was officially opened on 15 October by Queen Mary.[14] In 1962, the hospital became a registered charity.[16]

Prince Edward became the hospital's President in 1969 and President of its council four years later.[5][17]

General Sir Joseph Howard Nigel Poett recounted in his autobiography (1991) that Sister Agnes had arranged for his treatment to be transferred from Cambridge Hospital to King Edward VII's an that she "was a pretty powerful lady".[18]

21st Century

.jpg.webp)

The hospital works with the Wellington Barracks and with the Ministry of Defence, and has treated wounded officers of the War in Afghanistan and the Iraq War.[5] It has continued to support the treatment of all ranks of former servicemen, as well as the general public.[2] Through the hospital's Sister Agnes Benevolent Fund, active or retired personnel in the British armed services, as well as their spouses, can receive a means tested grant that can cover up to 100% of their hospital fees.[20] It has a pain management programme for veterans.[21]

In 2009, the year of the 40th anniversary of Prince Edward being president, the Michael Uren Foundation provided funds for a CT scan and the radiological information system was installed that same year. The following year, the four-bed Michael Uren critical care unit for high dependency and intensive care was opened by the Prince with the purpose of providing ventilation, haemofiltration and renal replacement therapy.[5]

Lord Stirrup has been on the Advisory Board of the hospital since 2016.[1] By 2018 there were 56 rooms and the hospital was treating over 4,000 people a year.[1] The hospital has more than 80 surgeons, operates with the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist, and its Theatre Officers Committee, made up of 12 surgeons, representing various surgical specialties, two anaesthetists, four nursing staff and the Chief Executive meet, quarterly.[5] In 2018, the CQC noted the hospital to have three operating theatres, a level three critical care unit, and radiology, outpatient and diagnostic facilities.[22] The use of the hydrotherapy pool, treatment of fractures, management of pain, and rehabilitation are available to injured soldiers.[5]

Royal hoax call and death of Jacintha Saldanha

In December 2012, the hospital received international media attention when Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge was admitted, suffering from hyperemesis gravidarum. While the Duchess was staying at the hospital, two DJs from the Australian radio station 2Day FM made a hoax telephone call to the hospital, pretending to be Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Charles.[23] They managed to obtain confidential information about the Duchess and her treatment from a nurse at the hospital. The call was recorded and broadcast after receiving approval from the station management. The hospital apologised, and said that privacy and security protocols would be reviewed.[24]

Two days after the broadcast, nurse Jacintha Saldanha, who had worked just over four years at the hospital and had passed on the hoax call to the other nurse in the Duchess's private ward, was found dead. The Metropolitan Police described it as an "unexplained death".[25][26][27] On 14 December, The Guardian reported that it understood that the third of the notes left by Saldanha "addressed her employers, the hospital, and contained criticism of staff there."[28]

Notable patients

- In recent years, the hospital has been used by various members of the British Royal Family. Previous royal patients at the hospital include Queen Elizabeth II, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, and Charles, Prince of Wales.[29]

- In February 2002, Princess Margaret died at the age of 71 at the hospital, after suffering a stroke.[30]

- In December 2013 it was announced that the hospital had received a donation of £30 million from Michael Uren.[31]

- In October 2014 Zambian President Michael Sata died at the age of 77 at the hospital, after receiving treatment for an undisclosed illness.[32]

Notable staff and members of Council

References

- Friend's Newsletter (PDF). King Edward VII's Hospital. 2018. pp. 5–6.

- "About Us". King Edward VII’s Hospital. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- "Celebrating 120 Years". King Edward VII’s Hospital. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Hough, Richard (1998). Sister Agnes. Chapter 1. The Keyser Origins, p.5-17

- Lee, Celia (2015). "2. Health Service Charities". HRH The Duke of Kent: A Life of Service. Seymour Books. ISBN 978-1-84396-351-6.

- Weir, Sue (February 1999). "Sister Agnes: The History of King Edward VII's Hospital for Officers 1899–1999". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 92 (2): 98–99. ISSN 0141-0768. PMID 1297078.

- Goddard, Jonathan C. (2014). "BAUS at war". BJU International. 113 (S5): 2–6. doi:10.1111/bju.12793. ISSN 1464-410X.

- Sir Peter Freyer's Papers. 1805-1987. NUI Galway. Reference code P57.

- "Medical news" (PDF). The British Medical Journal: 106. 9 January 1909. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Cloete, Stuart (1972) A Victorian Son, an autobiography, 1897-1922.

- Chris Schoeman (2017). The Historical Overberg: Traces of the Past in South Africa’s Southernmost Region. Penguin Random House South Africa. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-77609-073-0.

- Supermac. Author: D.R. Thorpe. Publisher: Chatto & Windus. Published: 9 September 2010. Retrieved: 1 February 2014.

- "King Edward VII'S hospital Sister Agnes- Charity 208944". register-of-charities.charitycommission.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- "Hospital For Service Officers - New Premises Opened by Queen Mary". Reviews. The Times (51204). London. 16 October 1948. pp. 6.

- "Medical news: King Edward VII's Hospital for Officers" (PDF). British Medical Journal: 765. 23 October 1948. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- The Charity Commission: King Edward VII's Hospital Sister Agnes - Registration history Linked 2016-01-29

- "Royal diary: upcoming royal engagements 17-23rd February 2020• The Crown Chronicles". The Crown Chronicles. 17 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- Poett, Nigel (1991). "2. Sandhurst". Pure Poett: The Autobiography of General Sir Nigel Poett. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-0850523393.

- Hough, Richard (1998). Sister Agnes. Chapter 9. Rebirth, p.115-29

- "Centre for Veterans' Health". Promoting veterans' health. 8 February 2017. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- "The Soldiers' Charity awards £22,380 to King Edward VII's Hospital's Pain Management Programme". The Soldiers' Charity. 9 May 2019. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- "King Edward VII's Hospital". www.cqc.org.uk. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Jacintha Saldanha, who died in suspected suicide after Kate Middleton radio hoax, was an 'excellent nurse'". National Post. Toronto. 7 December 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "Royal pregnancy: Hoax call fools Duchess of Cambridge hospital". BBC News. 5 December 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- "Duchess of Cambridge prank call nurse found dead in suspected suicide". Evening Standard. London. 7 December 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- Hall, John (7 December 2012). "Nurse who took prank phone call at Duchess of Cambridge's hospital is found dead in suspected suicide". The Independent. London. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- Vinograd, Cassandra; Kirka, Danica (8 December 2012). "Duchess of Cambridge prank call nurse dies". MSN News. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- "Jacintha Saldanha suicide notes". The Guardian. 14 December 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- "Kate admitted to hospital with royal connections". ITV. 4 December 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- "Scots sorrow at death of princess". BBC. 9 February 2002. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- "A gift fit for a Queen". Health Service Journal. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- "Zambian President Sata death: White interim leader appointed". BBC. 29 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- Great Britain. Army (1931). The Monthly Army List. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 49.

- Laura, Laura (22 July 2013). "Royal baby: Queen's gynaecologist leads top medical team". the Guardian. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

Bibliography

- Hough, Richard (1998). Sister Agnes: The History of King Edward VII's Hospital for Officers 1899-1999. Albemarle Street, London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5561-2.

Further reading

- Lamont-Brown, Raymond (2011). Alice Keppel and Agnes Keyser: Edward VII's Last Loves. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7394-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to King Edward VII's Hospital. |