Kish (Sumer)

Kish (Sumerian: Kiš; transliteration: Kiški; cuneiform: 𒆧𒆠;[1] Akkadian: kiššatu[2]) was an ancient tell (hill city) of Sumer in Mesopotamia, considered to have been located near the modern Tell al-Uhaymir in the Babil Governorate of Iraq, east of Babylon and 80 km (50 mi) south of Baghdad.[3][4]

._The_ruling_city_immediately_after_the_deluge._The_ancient_ruins_showing_extensive_remains_LOC_matpc.16176.jpg.webp) Ruins of Kish at time of excavation | |

| Location | Tell al-Uhaymir, Babil Governorate, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 32°32′25″N 44°36′17″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | Ubaid period |

| Periods | Ubaid to Hellenistic |

History

.svg.png.webp)

Kish was occupied from the Ubaid period (c.5300-4300 BC), gaining prominence as one of the pre-eminent powers in the region during the early dynastic period.[5]

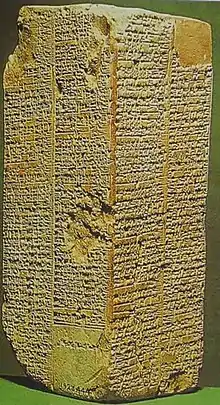

First Dynasty of Kish

The Sumerian king list states that Kish was the first city to have kings following the deluge,[6] beginning with Jushur. Jushur's successor is called Kullassina-bel, but this is actually a sentence in Akkadian meaning "All of them were lord". Thus, some scholars have suggested that this may have been intended to signify the absence of a central authority in Kish for a time. The names of the next nine kings of Kish preceding Etana are Nanjiclicma, En-tarah-ana, Babum, Puannum, Kalibum, Kalumum, Zuqaqip, Aba, Macda, and Arwium. These names are all Akkadian words for animals, e.g. Zuqaqip "scorpion". The East Semitic nature of these and other early names associated with Kish reveals that its population had a strong Semitic (Akkadian speaking) component from the dawn of recorded history.[7] Ignace Gelb identified Kish as the center of the earliest East Semitic culture which he calls the Kish civilization.[8] After the twelve kings a massive flood devastated Mesopotamia. According to the Sumerians, after the flood Ishtar gave the kingship to Etana.[9] Ancient Sumerian sources describe Etana as 'the shepherd who ascended to Heaven and made firm all the lands'.[9] This implies that the historical Etana stabilized the kingdom by bringing peace and order to the area after the Flood.[9] Etana is also sometimes credited with the founding of Kish.

The twenty-first king of Kish on the list, Enmebaragesi, who is said to have captured the weapons of Elam, is the first name confirmed by archaeological finds from his reign. He is also known through other literary references, in which he and his son Aga of Kish are portrayed as contemporary rivals of Dumuzid, the Fisherman, and Gilgamesh, early rulers of Uruk.

Some early kings of Kish are known through archaeology, but are not named on the King list. These include Utug or Uhub, said to have defeated Hamazi in the earliest days, and Mesilim, who built temples in Adab and Lagash, where he seems to have exercised some control.

Third Dynasty of Kish (ca. 2500–2330 BC)

.jpg.webp)

The Third Dynasty of Kish is unique in that it begins with a woman, previously a tavern keeper, Kubau, as "king". She was later deified as the goddess Kheba.

Afterwards, although its military and economic power was diminished, Kish retained a strong political and symbolic significance. Just as with Nippur to the south, control of Kish was a prime element in legitimizing dominance over the north of Mesopotamia (Assyria, Subartu). Because of the city's symbolic value, strong rulers later claimed the traditional title "King of Kish", even if they were from Akkad, Ur, Assyria, Isin, Larsa or Babylon. One of the earliest to adopt this title upon subjecting Kish to his empire was King Mesannepada of Ur, as well as Mesilim.[13] A few governors of Kish for other powers in later times are also known, including Ashduniarim and Iawium.[14]

Sargon of Akkad, the founder of the Akkadian Empire, came from the area nearby Kish, called Azupiranu. He would later declare himself the king of Kish, as an attempt to signify his connection to the religiously important area. In Akkadian times the city's patron deity was Zababa (or Zamama), along with his wife, the goddess Inanna.

Later history

After the fall of the Akkadian Empire, Kish became the capital of a small independent kingdom. One king, named Ashduniarim, ruled around the same time as Lipit-Ishtar of Isin. By the early part of the First Dynasty of Babylon, during the reigns of Sumu-abum and Sumu-la-El, Kish appears to have come under the rule of another city-state, possibly Kutha. Iawium, king of Kish around this time, ruled as a vassal of kings named Halium and Manana. Sumu-la-El conquered Kish and, later, subjugated Halium and Manana, bringing their territories into the expanding Babylonian Empire. The First Dynasty kings Hammurabi and Samsu-iluna undertook construction at Kish, with the former restoring the city's ziggurat and the latter building a wall around Kish. By this time, the eastern settlement at Hursagkalama had become viewed as a distinct city, and it was probably not included in the walled area.[15]

After the Old Babylonian period, however, Kish appears to have declined in importance; it is only mentioned in a few documents from the later second millennium BCE. During the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian periods, Kish is mentioned more frequently in texts. However, by this time, Kish proper (Tell al-Uhaymir) had been almost completely abandoned, and the settlement that texts from this period call "Kish" was probably Hursagkalama (Tell Ingharra).[15]

After the Achaemenid period, Kish completely disappears from the historical record; however, archaeological evidence indicates that the town remained in existence for a long time thereafter.[15] Although the site at Tell al-Uhaymir was mostly abandoned, Tell Ingharra was revived during the Parthian period, growing into a sizeable town with a large mud-brick fortress. During the Sasanian period, the site of the old city was completely abandoned in favor of a string of connected settlements spread out along both sides of the Shatt en-Nil canal. This last incarnation of Kish prospered under Sasanian and then Islamic rule, before finally abandoned during the later years of the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258). [16]

Archaeology

The Kish archaeological site is an oval area roughly 8 by 3 km (5 by 2 mi), transected by the dry former bed of the Euphrates River, encompassing around 40 mounds, the largest being Uhaimir and Ingharra. The most notable mounds are:

- Tell Uhaimir – believed to be the location of the city of Kish. It means "the red" after the red bricks of the ziggurat there.

- Tell Ingharra – believed to be the location of Hursagkalamma, east of Kish home of a temple of Inanna.[17]

- Tell Khazneh

- Tell el-Bender – held Parthian material

- Mound W – where a number of Neo-Assyrian tablets were discovered

After irregularly excavated tablets began appearing at the beginning of the twentieth century, François Thureau-Dangin identified the site as being Kish. Those tablets ended up in a variety of museums.

Because of its close proximity to Babylon the site was visited by a number of explorers and travelers in the 19th century, some involving excavation, most notably by the foreman of Hormuzd Rassam who dug there with a crew of 20 men for a number of months. None of this early work was published. A French archaeological team under Henri de Genouillac excavated at Tell Uhaimir between 1912 and 1914, finding some 1,400 Old Babylonian tablets which were distributed to the Istanbul Archaeology Museum and the Louvre. [18][19] Later, a joint Field Museum and University of Oxford team under Stephen Langdon excavated from 1923 to 1933, with the recovered materials split between Chicago and the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26]

The actual excavations at Tell Uhaimir were led initially by E. MacKay and later by L. C. Watelin. Work on the faunal and flora remains was conducted by Henry Field.[27][28]

More recently, a Japanese team from the Kokushikan University led by Ken Matsumoto excavated at Tell Uhaimir in 1988, 2000, and 2001. The final season lasted only one week.[29][30][31]

Gallery

Ruins of a ziggurat at the Sumerian city of Kish. Babel Governorate, Iraq.

Ruins of a ziggurat at the Sumerian city of Kish. Babel Governorate, Iraq. An ancient mound at Kish, Babel Governorate, Iraq

An ancient mound at Kish, Babel Governorate, Iraq An ancient mound at the city of Kish, Mesopotamia, Babel Governorate, Iraq

An ancient mound at the city of Kish, Mesopotamia, Babel Governorate, Iraq Pottery fragments, illegal exavations at the ancient city of Kish, Tell al-Uhaymir, Iraq

Pottery fragments, illegal exavations at the ancient city of Kish, Tell al-Uhaymir, Iraq Ancient mound at the city of Kish, Mesopotamia, Babil Governorate, Iraq

Ancient mound at the city of Kish, Mesopotamia, Babil Governorate, Iraq Ruins near the ziggurat of Kish at Tell al-Uhaymir, Mesopotamia, Babel Governorate, Iraq

Ruins near the ziggurat of Kish at Tell al-Uhaymir, Mesopotamia, Babel Governorate, Iraq Ruins near the ziggurat of Kish, Tell al-Uhaymir, Babylon Governorate, Iraq

Ruins near the ziggurat of Kish, Tell al-Uhaymir, Babylon Governorate, Iraq Ruins near the ziggurat of the city of Kish at Tell al-Uhaymir, Babel Governorate, Iraq

Ruins near the ziggurat of the city of Kish at Tell al-Uhaymir, Babel Governorate, Iraq Ruins of the ziggurat of the ancient city of Kish, Tell al-Uhaymir, Mesopotamia, Iraq

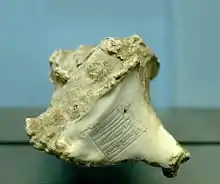

Ruins of the ziggurat of the ancient city of Kish, Tell al-Uhaymir, Mesopotamia, Iraq Indus Valley Civilisation "Unicorn" seal excavated in Kish, early Sumerian period, circa 3000 BCE. An example of ancient Indus-Mesopotamia relations.[32]

Indus Valley Civilisation "Unicorn" seal excavated in Kish, early Sumerian period, circa 3000 BCE. An example of ancient Indus-Mesopotamia relations.[32]

Rulers of Kish

The Sumerian King List gives a list of the rulers of the four dynasties of Kish.

First dynasty of Kish

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Jushur | 1,200 years | historicity uncertain | names before Etana do not appear in any other known source, and their existence is archaeologically unverified | |

| Kullassina-bel | 960 years | The name is an Akkadian phrase meaning "All of them (were) lord", which may denote a period of no central authority in the early period of Kish. | ||

| Nangishlishma | 670 years | |||

| En-tarah-ana | 420 years | |||

| Babum | 300 years | |||

| Puannum | 840 years | |||

| Kalibum | 960 years | The name is believed to be Akkadian for 'hound'. | ||

| Kalumum | 840 years | The name means akkadian for lamb | ||

| Zuqaqip | 900 years | The name means scorpion. | ||

| Atab (or A-ba) | 600 years | |||

| Mashda | "the son of Atab" | 840 years | The name is Akkadian for "gazelle". | |

| Arwium | "the son of Mashda" | 720 years | The name means male gazelle in akkadian. | |

| Etana | "the shepherd, who ascended to heaven and consolidated all the foreign countries" | 1,500 years | Babylonian myth of etana is recorded | |

| Balih | "the son of Etana" | 400 years | Nothing is known about the ruler. | |

| En-me-nuna | 660 years | Nothing is known about the ruler. | ||

| Melem-Kish | "the son of En-me-nuna" | 900 years | Nothing is known about the ruler. | |

| Barsal-nuna | ("the son of En-me-nuna")* | 1,200 years | His name may have meant sheep of the prince. Barsal means sheep. | |

| Zamug | "the son of Barsal-nuna" | 140 years | Nothing is known about the ruler | |

| Tizqar | "the son of Zamug" | 305 years | Nothing is known about the ruler | |

| Ilku | 900 years | Nothing is known about the ruler | ||

| Iltasadum | 1,200 years | Nothing is known about the ruler | ||

| En-me-barage-si | "who made the land of Elam submit" | 900 years | c. 2600 BC | the earliest ruler on the List confirmed independently from epigraphical evidence and can be historically verified with archaeology |

| Aga of Kish | "the son of En-me-barage-si" | 625 years | c. 2600 BC | contemporary with Gilgamesh of Uruk, according to the Sumerian tale of Gilgamesh and Aga[33] |

| ||||

Second dynasty of Kish

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susuda | "the fuller" | 201 years | c. 26th century BC | |

| Dadasig | 81 years | |||

| Mamagal | "the boatman" | 360 years | ||

| Kalbum | "the son of Mamagal" | 195 years | ||

| Tuge | 360 years | |||

| Men-nuna | "the son of Tuge" | 180 years | ||

| (Enbi-Ishtar) | 290 years | |||

| Lugalngu | 360 years | |||

| ||||

Third dynasty of Kish

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kug-Bau (Kubaba) | "the woman tavern-keeper, who made firm the foundations of Kish" | 100 years | c. 25th century BC | the only known woman in the King List; said to have gained independence from En-anna-tum I of Lagash and En-shag-kush-ana of Uruk; contemporary with Puzur-Nirah of Akshak, according to the later Chronicle of the É-sagila |

| ||||

Fourth dynasty of Kish

| Ruler | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puzur-Suen | "the son of Kug-Bau" | 25 years | c. 2350 BC | Nothing is known about the ruler besides the fact that he is the son of Kug-bau |

| Ur-Zababa | "the son of Puzur-Suen" | 400 (6?) years | c. 2350 BC | according to the king list, Sargon of Akkad was his cup-bearer |

| Zimudar | 30 years | |||

| Usi-watar | "the son of Zimudar" | 7 years | ||

| Eshtar-muti | 11 years | |||

| Ishme-Shamash | 11 years | |||

| (Shu-ilishu)* | (15 years)* | |||

| Nanniya | "the jeweller" | 7 years | ||

| ||||

Notes

- The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature

- Electronic Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary (EPSD)

- "Kish | ancient city, Iraq". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- wparkinson (2011-01-11). "The Kish Collection". Field Museum. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- Weiss, Harvey, and Mcguire Gibson. “Kish, Akkad and Agade.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 95, no. 3, 1975, p. 434., doi:10.2307/599355.

- Hall, John Whitney, ed. (2005) [1988]. "The Ancient Near East". History of the World: Earliest Times to the Present Day. John Grayson Kirk. 455 Somerset Avenue, North Dighton, MA 02764, USA: World Publications Group. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-57215-421-6.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Cambridge Ancient History, p. 100

- Donald P. Hansen, Erica Ehrenberg (2002). Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen. p. 133. ISBN 9781575060552.

- "Kingdoms of Mesopotamia - Kish / Kic". www.historyfiles.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 312.

- Image of a Mesanepada seal in: Legrain, Léon (1936). UR EXCAVATIONS VOLUME III ARCHAIC SEAL-IMPRESSIONS (PDF). THE TRUSTEES OF THE TWO MUSEUMS BY THE AID OF A GRANT FROM THE CARNEGIE CORPORATION OF NEW YORK. p. 44 seal 518 for description, Plate 30, seal 518 for image.

- Hall, H. R. (Harry Reginald); Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1900). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 312.

- Albrecht Goetze, Early Kings of Kish, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 105–111, 1961

- McGuire Gibson, The city and Area of Kish, Field Research Projects, Coconut Grove, 1972

- Gibson, The City and Area of Kish, pp. 2-5

- Gibson, The City and Area of Kish, pp. 59-60

- Inanna's Descent to the Underworld translation at ETCSL

- Henri de Genouillac, Premières recherches archéologiques à Kich : mission d'Henri de Genouillac 1911-1912 : rapport sur les travaux et inventaires, fac-similés, dessins, photographies et plans. Tome premier, Paris : Libr. ancienne Edouard Champion, 5, quai Malaquais, 1924

- Henri de Genouillac, Fouilles françaises d'El-Akhymer, Champion, 1924–25

- Stephen Langdon, Excavations at Kish I (1923–1924), 1924

- Stephen Langdon and L. C. Watelin, Excavations at Kish III (1925–1927), 1930

- Stephen Langdon and L. C. Watelin, Excavations at Kish IV (1925–1930), 1934

- Henry Field, The Field Museum-Oxford University expedition to Kish, Mesopotamia, 1923–1929, Chicago, Field Museum of Natural History, 1929

- P. R. S. Moorey, Kish excavations, 1923–1933 : with a microfiche catalogue of the objects in Oxford excavated by the Oxford-Field Museum, Chicago, Expedition to Kish in Iraq, Clarendon Press, 1978, ISBN 0-19-813191-7

- S. Langdon and D. B. Harden, Excavations at Kish and Barghuthiat 1933, Iraq, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 113–136, 1934

- S. D. Ross, 'The excavations at Kish. With special reference to the conclusions reached in 1928–29', in Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society, vol. 17, iss. 3, pp. 291–300, 1930

- Henry Field, Ancient Wheat and Barley from Kish Mesopotamia, American Anthropologist, New Series, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 303-309, 1932

- L. H. Dudley Buxton and D. Talbot Rice, Report on the Human Remains Found at Kish, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 61, pp. 57–119, 1931

- K. Matsumoto, Preliminary Report on the Excavations at Kish/Hursagkalama 1988–1989, al-Rāfidān 12, pp. 261-307, 1991

- K. Matsumoto and H. Oguchi, Excavations at Kish, 2000, al-Rāfidān, vol. 23, pp. 1–16, 2002

- K. Matsumoto and H. Oguchi, News from Kish: The 2001 Japanese Work, al-Rafidan, vol. 25, pp. 1–8, 2004

- MacKay, Ernest (1925). "Sumerian Connexions with Ancient India". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (4): 698–699. JSTOR 25220818.

- Archived 2016-10-09 at the Wayback Machine Gilgameš and Aga Translation at ETCSL

References

- E. Mackay, Report on the Excavation of the "A" Cemetery at Kish, Mesopotamia, Pt. 1, A Sumerian Palace and the "A" Cemetery, Pt. 2 (Anthropology Memoirs I, 1-2), Chicago: Field Museum,1931

- Nissen, Hans The early history of the ancient Near East, 9000–2000 B.C. (Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 1988. ISBN 0-226-58656-1, ISBN 0-226-58658-8) Elizabeth Lutzeir, trans.

- I. J. Gelb, Sargonic Texts in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Materials for the Assyrian Dictionary 5, University of Chicago Press, 1970 ISBN 0-226-62309-2

- McGuire Gibson, The Archaeological uses of Cuneiform Documents: Patterns of Occupation at the City of Kish, Iraq, vol. 34, iss. 2, pp. 113–123, Autumn 1972

- Gibson, McGuire (1972). The City and Area of Kish. Miami: Field Research Projects. pp. 53–55, 155.

- T. Claydon, Kish in the Kassite Period (c. 1650 – 1150 B.C), Iraq, vol. 54, pp. 141–155, 1992

- P. R. S. Moorey, A Re-Consideration of the Excavations on Tell Ingharra (East Kish) 1923-33, Iraq, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 18–51, 1966

- P. R. S. Moorey, The Terracotta Plaques from Kish and Hursagkalama, c. 1850 to 1650 B.C., Iraq, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 79–99, 1975

- P. R. S. Moorey, 1978 Kish Excavation 1923 – 1933 (Oxford: Oxford Press, 1978).

- Norman Yoffee, The Economics of Ritual at Late Old Babylonian Kish, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 312–343, 1998

- P. R. S. Moorey, The "Plano-Convex Building" at Kish and Early Mesopotamian Palaces, Iraq, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 83–98, 1964

- P. R. S. Moorey, Cemetery A at Kish: Grave Groups and Chronology, Iraq, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 86–128, 1970

- Weiss, Harvey, and Mcguire Gibson. “Kish, Akkad and Agade.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 95, no. 3, 1975, doi:10.2307/599355.

- Wu Yuhong and Stephanie Dalley, The Origins of the Manana Dynasty at Kish and the Assyrian King List, Iraq, vol. 52, pp. 159–165, 1990

- Seton Lloyd, Back to Ingharra: Some Further Thoughts on the Excavations at East Kish, Iraq, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 40–48, 1969

- Federico Zaina, Radiocarbon date from Early Dynastic Kish and the stratigraphy and chronology of the YWN Sounding at Tell Ingharr, Iraq, vol. 77(1), pp. 225–234, 2015

- Zaina, F., Craft, Administration and Power in Early Dynastic Mesopotamian Public Buildings. Recovering the Plano-convex Building at Kish, Iraq, Paléorient, vol. 41, p. 177–197, 2015

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kish (Mesopotamia). |

- Online Kish Collection at the Field Museum

- YouTube video on Field Museum Kish effort

- Kish Site photographs at Oriental Institute of Chicago

- The gold helmet worn by a Sumerian King of Kish.