Lake Chad replenishment project

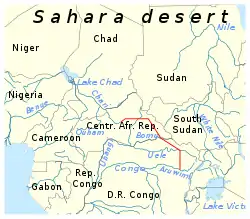

The Lake Chad replenishment project is a proposed major water diversion scheme that would involve damming the right tributaries of the Congo river, channeling some of the water to Lake Chad through a navigable canal.[1] [2]

The canal, named Transaqua, was proposed by a team of engineers of the firm Bonifica,[3][4] led by Dr. Marcello Vichi,[5] and would generate hydro-electricity at several points along its length. These would power new industrial townships, while the canal would replenish the lake.[6] The irrigation scheme for a 2,400 km canal from the Congo Basin to the lake, which has been steadily shrinking, was considered unlikely to materialize as late as 2005.[7]

The members of the Lake Chad Basin International Commission are Chad, the Central African Republic, Nigeria, Cameroon and Niger. Concerned by shrinkage of the lake's area from 20,000 square kilometres (7,700 sq mi) in 1972 to 2,000 square kilometres (770 sq mi) in 2002, they met in January 2002 to discuss the project. Both the ADB and the Islamic Development Bank expressed interest in the project. However, the member states of the Congo-Ubangi-Sangha Basin International Commission, Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville and the Central African Republic expressed concern that the project would reduce the energy potential of the Inga hydroelectric dam, would affect navigation on the Ubangi and Congo rivers and would reduce fish catches on these rivers.[8]

These objections overlook the fact that only 5-8% of the water would be diverted, while the rest 92-95% would not only reach Inga, but would produce electricity twice, first at the Transaqua dams and eventually at Inga.

Initially judged as too ambitious, Transaqua was rejected in favor of a smaller water-transfer scheme from the Ubangui, the biggest tributary of the Congo river and the Canadian firm CIMA was commissioned a feasibility study. The Lake Chad Basin Commission, however, judged the project, which involved pumping water upwards from the Ubangui river, was not sufficient to replenish Lake Chad and adopted Transaqua as the "only feasible" project at the International Conference on Lake Chad, on Feb. 26-28, 2018.[9] [10]

Following the ICLC, representatives of the LCBC and the Italian government signed a MoU for initial funding for the Transaqua feasibility study on Oct. 16, 2018.[11]

On Dec. 16, 2019, an amendment introduced by Italian Sen. Tony Iwobi to the 2021 Italian budget law included a financing of 1.5 million Euro for the feasibility study.[12]

On Nov. 13, 2020, Former Italian Prime Minister, former EU Commission chief and former UN Special Envoy for the Sahel Romano Prodi stated that the populations around Lake Chad could not wait any longer and called for the EU, the UNO, the Organization for African Unity and China to join hands to finance and build Transaqua.[13]

A large merit for the success of Transaqua has been attributed to activists from the LaRouche movement.[14] [15]

Alternative inland waterway

An inland waterway from Ubangi River to Chari River), around 366 km channel, from Gigi river (close to Djoukou - Galabadja in Kémo), through Sibut, Bouca and then to Batangafo (over Boubou river and into Ouham River and then Chari river).

This path is the used by the CIMA (Canada) study (water flow 100m3/s) made in contract of the Lake Chad Basin Commission (same water flow as the Moscow Canal), only sizing the channel and adapting the river and lock (water navigation).

Chad-Congo inland waterway

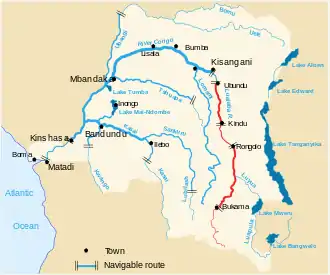

This waterway can link the lake Chad with the Congo River inland navigation system and the waterway transport in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The navigable waterway system in Congo can be upgraded from Kinshasa to Matadi sea port, already planned as an option in the Inga dams project.

As well as it is "feasible" from Lake Mweru (Pweto city) through Luvua River to Ankoro (requiring dams and Boat lift in Boyoma Falls,... as the Three Gorges dam ship lift), or the waterway into the Lake Tanganyika in Kalemie through the Lukuga River up to Kabalo (Zanza village), now link by railway.

Other World main channels

A channel Ubangi-Chari is double the distance of the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal, but half the distance of the Saint Lawrence Seaway that link the Great Lakes Waterway (waterway from New Orleans to Quebec), three times the Moscow Canal (100-130m3/s) or Volga–Don Canal, a third of the Volga–Baltic Waterway (that form the Unified Deep Water System of European Russia), and 5 times shorter than the 1974 Km Grand Canal (China) (build in the Sui dynasty).

References

- Abiodun Alao (2007). Natural resources and conflict in Africa: the tragedy of endowment. University Rochester Press. p. 323k. ISBN 1-58046-267-7.

- "Transaqua Progetto Interafrica". transaquaproject.it. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- Ross, Will (2018-03-31). "Can the vanishing lake be saved?". Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- "Bonifica SpA". bonificagroup.com. Renardet SA. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- "La storia del progetto". transaquaproject.it. Transaqua Project. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- Graham Chapman, Kathleen M. Baker (1992). The Changing geography of Africa and the Middle East. Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 0-415-05710-8.

- Michele L. Thieme (2005). Freshwater ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: a conservation assessment. Island Press. p. 195. ISBN 1-55963-365-4.

- Europa Publications Limited (2002). Africa South of the Sahara 2003. Routledge. p. 266. ISBN 1-85743-131-6.

- Celani, Claudio (March 9, 2018). "Conference on Lake Chad Is Historic Breakthrough for Development of Africa" (PDF). larouchepub.com. EIR News Service Inc. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- "Nigeria: une «déclaration d'Abuja» pour tenter de sauver le lac Tchad". rfi.fr. France Médias Monde. March 1, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- "Commission du Bassin du Lac Tchad". cblt.org. La Commission du Bassin du Lac Tchad. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- Iwobi, Tony Chike (December 16, 2019). "Proposta di modifica n. 101.0.37 (testo 2) al DDL n. 1586". senato.it. Senato della Repubblica Italiana. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- Live Roundtable on the Lake Chad: the diplomatic dialogue on YouTube

- Lawton, P.D. (October 18, 2020). "Green Power, Political Pessimism and Opposition to the Development of the African Interior with Transaqua". africanagenda.net. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- Sayan, Ramazan Caner; Nagabhatla, Nidhi; Ekwuribe, Marvel (2020). "Soft Power, Discourse Coalitions, and the Proposed Interbasin Water Transfer Between Lake Chad and the Congo River". water-alternatives.org. Water Alternatives. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

External links

- Transaqua Progetto Interafrica

- Web of the Water transfer project, Study of CIMA International (Canada) under contract from Lake Chad Basin Commission. Same path as the proposed waterway, adapting it for inland navigation.