Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika is an African Great Lake. It is the second-oldest freshwater lake in the world, the second-largest by volume, and the second-deepest, in all cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia.[4][5] It is the world's longest freshwater lake.[4] The lake is shared between four countries – Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Burundi, and Zambia, with Tanzania (46%) and DRC (40%) possessing the majority of the lake. It drains into the Congo River system and ultimately into the Atlantic Ocean.

| Lake Tanganyika | |

|---|---|

Lake Tanganyika from space, June 1985 | |

Lake Tanganyika | |

Lake Tanganyika map | |

| Coordinates | 6°30′S 29°50′E |

| Lake type | Ancient lake, Rift Valley Lake |

| Primary inflows | Ruzizi River Malagarasi River Kalambo River |

| Primary outflows | Lukuga River |

| Catchment area | 231,000 km2 (89,000 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | Burundi, DR Congo, Tanzania, and Zambia |

| Max. length | 673 km (418 mi) |

| Max. width | 72 km (45 mi) |

| Surface area | 32,900 km2 (12,700 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 570 m (1,870 ft) |

| Max. depth | 1,470 m (4,820 ft) |

| Water volume | 18,900 km3 (4,500 cu mi) |

| Residence time | 5500 years[1] |

| Shore length1 | 1,828 km (1,136 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 773 m (2,536 ft)[2] |

| Settlements | Kigoma, Tanzania Kalemie, DRC Bujumbura, Burundi |

| References | [2] |

| Official name | Tanganyika |

| Designated | 2 February 2007 |

| Reference no. | 1671[3] |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

Etymology

The name "Tanganyika" apparently refers to "the great lake spreading out like a plain", or "plain-like lake".[6]:Vol.Two,16

Geography and geological history

Lake Tanganyika is situated within the Albertine Rift, the western branch of the East African Rift, and is confined by the mountainous walls of the valley. It is the largest rift lake in Africa and the second-largest lake by volume in the world. It is the deepest lake in Africa and holds the greatest volume of fresh water, accounting for 16% of the world's available fresh water. It extends for 676 km (420 mi) in a general north-south direction and averages 50 km (31 mi) in width. The lake covers 32,900 km2 (12,700 sq mi), with a shoreline of 1,828 km (1,136 mi), a mean depth of 570 m (1,870 ft) and a maximum depth of 1,471 m (4,826 ft) (in the northern basin). It holds an estimated 18,900 km3 (4,500 cu mi).[7]

The catchment area of the lake is 231,000 km2 (89,000 sq mi). Two main rivers flow into the lake, as well as numerous smaller rivers and streams (whose lengths are limited by the steep mountains around the lake). The one major outflow is the Lukuga River, which empties into the Congo River drainage. Precipation and evaporation play a greater role than the rivers. At least 90% of the water influx is from rain falling on the lake's surface and at least 90% of the water loss is from direct evaporation.[8]

The major river flowing into the lake is the Ruzizi River, formed about 10,000 years ago, which enters the north of the lake from Lake Kivu.[9] The Malagarasi River, which is Tanzania's second largest river, enters the east side of Lake Tanganyika.[9] The Malagarasi is older than Lake Tanganyika, and before the lake was formed, it probably was a headwater of the Lualaba River, the main Congo River headstream.[8]

The lake has a complex history of changing flow patterns, due to its high altitude, great depth, slow rate of refill, and mountainous location in a turbulently volcanic area that has undergone climate changes. Apparently, it has rarely in the past had an outflow to the sea. It has been described as "practically endorheic" for this reason. The lake's connection to the sea is dependent on a high water level allowing water to overflow out of the lake through the Lukuga River into the Congo.[9] When not overflowing, the lake's exit into the Lukuga River typically is blocked by sand bars and masses of weed, and instead this river depends on its own tributaries, especially the Niemba River, to maintain a flow.[8]

Due to the lake's tropical location, it has a high rate of evaporation. Thus, it depends on a high inflow through the Ruzizi out of Lake Kivu to keep the lake high enough to overflow. This outflow is apparently not more than 12,000 years old, and resulted from lava flows blocking and diverting the Kivu basin's previous outflow into Lake Edward and then the Nile system, and diverting it to Lake Tanganyika. Signs of ancient shorelines indicate that at times, Tanganyika may have been up to 300 m (980 ft) lower than its present surface level, with no outlet to the sea. Even its current outlet is intermittent, thus may not have been operating when first visited by Western explorers in 1858.

The lake may also have at times had different inflows and outflows; inward flows from a higher Lake Rukwa, access to Lake Malawi and an exit route to the Nile have all been proposed to have existed at some point in the lake's history.[10]

Lake Tanganyika is an ancient lake. Its three basins, which in periods with much lower water levels were separate lakes, are of different ages. The central began to form 9–12 million years ago (Mya), the northern 7–8 Mya and the southern 2–4 Mya.[11]

Islands

Of the several islands in Lake Tanganyika, the most important are:

- Kavala Island (DRC)

- Mamba-Kayenda Islands (DRC)

- Milima Island (DRC)

- Kibishie Island (DRC)

- Mutondwe Island (Zambia)

- Kumbula Island (Zambia)

Water characteristics

The lake's water is alkaline with a pH around 9 at depths of 0–100 m (0–330 ft).[12] Below this, it is around 8.7, gradually decreasing to 8.3–8.5 in the deepest parts of Tanganyika.[12] A similar pattern can be seen in the electric conductivity, ranging from about 670 μS/cm in the upper part to 690 μS/cm in the deepest.[12]

Surface temperatures generally range from about 24 °C (75 °F) in the southern part of the lake in early August to 28–29 °C (82–84 °F) in the late rainy season in March—April.[13] At depths greater than 400 m (1,300 ft), the temperature is very stable at 23.1–23.4 °C (73.6–74.1 °F).[14] The water has gradually warmed since the 19th century and this has accelerated with global warming since the 1950s.[15]

The lake is stratified and seasonal mixing generally does not extend beyond depths of 150 m (490 ft).[13] The mixing mainly occurs as upwellings in the south and is wind-driven, but to a lesser extent, up- and downwellings also occur elsewhere in the lake.[16] As a consequence of the stratification, the deep sections contain "fossil water".[17] This also means it has no oxygen (it is anoxic) in the deeper parts, essentially limiting fish and other aerobic organisms to the upper part. Some geographical variations are seen in this limit, but it is typically at depths around 100 m (330 ft) in the northern part of the lake and 240–250 m (790–820 ft) in the south.[18][19] The oxygen-devoid deepest sections contain high levels of toxic hydrogen sulphide and are essentially lifeless,[4] except for bacteria.[12][20]

Biology

Reptiles

Lake Tanganyika and associated wetlands are home to Nile crocodiles (including famous giant Gustave), Zambian hinged terrapins, serrated hinged terrapins, and pan hinged terrapins (last species not in the lake itself, but in adjacent lagoons).[21] Storm's water cobra, a threatened subspecies of banded water cobra that feeds mainly on fish, is only found in Lake Tanganyika, where it prefers rocky shores.[21][22]

Cichlid fish

The lake holds at least 250 species of cichlid fish[26] and undescribed species remain.[27] Almost all (98%) of the Tanganyika cichlids are endemic to the lake and it is thus an important biological resource for the study of speciation in evolution.[28][29] Some of the endemics do occur slightly into the upper Lukuga River, Lake Tanganyika's outflow, but further spread into the Congo River basin is prevented by physics (Lukuga has fast-flowing sections with many rapids and waterfalls) and chemistry (Tanganyika's water is alkaline, while the Congo's generally is acidic).[8] The cichlids of the African Great Lakes, including Tanganyika, represent the most diverse extent of adaptive radiation in vertebrates.[30]

Although Tanganyika has far fewer cichlid species than Lakes Malawi and Victoria which both have experienced relatively recent explosive species radiations (resulting in many closely related species),[31] its cichlids are the most morphologically and genetically diverse.[30][32] This is linked to the high age of Tanganyika, as it is far older than the other lakes.[33] Tanganyika has the largest number of endemic cichlid genera of all African lakes.[30] All Tanganyika cichlids are in the subfamily Pseudocrenilabrinae. Of the 10 tribes in this subfamily, half are largely or entirely restricted to the lake (Cyprichromini, Ectodini, Lamprologini, Limnochromini and Tropheini) and another three have species in the lake (Haplochromini, Tilapiini and Tylochromini).[34] Others have proposed splitting the Tanganyika cichlids into as many as 12–16 tribes (in addition to previous mentioned, Bathybatini, Benthochromini, Boulengerochromini, Cyphotilapiini, Eretmodini, Greenwoodochromini, Perissodini and Trematocarini).[30]

Most Tanganyika cichlids live along the shoreline down to a depth of 100 m (330 ft), but some deep-water species regularly descend to 200 m (660 ft).[35] Trematocara species have exceptionally been found at more than 300 m (980 ft), which is deeper than any other cichlid in the world.[36] Some of the deep-water cichlids (e.g., Bathybates, Gnathochromis, Hemibates and Xenochromis) have been caught in places virtually devoid of oxygen, but how they are able to survive there is unclear.[19] Tanganyika cichlids are generally benthic (found at or near the bottom) and/or coastal.[37] No Tanganyika cichlids are truly pelagic and offshore, except for some of the piscivorous Bathybates.[35] Two of these, B. fasciatus and B. leo, mainly feed on Tanganyika sardines.[35][19] Tanganyika cichlids differ extensively in ecology and include species that are herbivores, detritivores, planktivores, insectivores, molluscivores, scavengers, scale-eaters and piscivores.[27] Their breeding behavior fall into two main groups, the substrate spawners (often in caves or rock crevices) and the mouthbrooders.[38] Among the endemic species are two of the world's smallest cichlids, Neolamprologus multifasciatus and N. similis (both shell dwellers) at up to 4–5 cm (1.6–2.0 in),[39][40] and one of the largest, the giant cichlid (Boulengerochromis microlepis) at up to 90 cm (3.0 ft).[27][41]

Many cichlids from Lake Tanganyika, such as species from the genera Altolamprologus, Cyprichromis, Eretmodus, Julidochromis, Lamprologus, Neolamprologus, Tropheus and Xenotilapia, are popular aquarium fish due to their bright colors and patterns, and interesting behaviors.[38] Recreating a Lake Tanganyika biotope to host those cichlids in a habitat similar to their natural environment is also popular in the aquarium hobby.[38][42]

- Cichlid tribes in Lake Tanganyika (E = tribe endemic or near-endemic)

Bathybatini (E): Bathybates ferox is benthic and piscivorous, but the genus also includes pelagic species.[35] The tribe is sometimes split in three, others being Hemibatini and Trematocarini[43][44]

Bathybatini (E): Bathybates ferox is benthic and piscivorous, but the genus also includes pelagic species.[35] The tribe is sometimes split in three, others being Hemibatini and Trematocarini[43][44] Benthochromini (E): Benthochromis horii was scientifically described in 2008, but has often been misidentifed as B. tricoti[45]

Benthochromini (E): Benthochromis horii was scientifically described in 2008, but has often been misidentifed as B. tricoti[45] Boulengerochromini (E): Boulengerochromis microlepis is one of the world's largest cichlids[41] and only member of its tribe[44]

Boulengerochromini (E): Boulengerochromis microlepis is one of the world's largest cichlids[41] and only member of its tribe[44]

Cyprichromini (E): Cyprichromis microlepidotus and other members of this tribe are open-water planktivores[47][48]

Cyprichromini (E): Cyprichromis microlepidotus and other members of this tribe are open-water planktivores[47][48] Ectodini (E): Ophthalmotilapia nasuta (male) is sexually dimorphic, males being more colorful with longer fins and nose[49]

Ectodini (E): Ophthalmotilapia nasuta (male) is sexually dimorphic, males being more colorful with longer fins and nose[49] Eretmodini (E): Eretmodus cyanostictus lives near the bottom in the turbulent, coastal surf zone,[50] like other members of its tribe[48]

Eretmodini (E): Eretmodus cyanostictus lives near the bottom in the turbulent, coastal surf zone,[50] like other members of its tribe[48] Haplochromini: Astatotilapia burtoni is one of the few Tanganyika species,[51] unlike other African Great Lakes where most belong to this tribe[52]

Haplochromini: Astatotilapia burtoni is one of the few Tanganyika species,[51] unlike other African Great Lakes where most belong to this tribe[52] Lamprologini (E): Julidochromis marlieri is popular in the aquarium trade where members of the genus are known as "Julies"[53]

Lamprologini (E): Julidochromis marlieri is popular in the aquarium trade where members of the genus are known as "Julies"[53] Limnochromini (E): Gnathochromis permaxillaris is a zooplanktivore with an unusual protractile mouth[54]

Limnochromini (E): Gnathochromis permaxillaris is a zooplanktivore with an unusual protractile mouth[54]

.jpg.webp) Tilapiini: Oreochromis tanganicae is one of the most common coastal species found in local fish markets[56]

Tilapiini: Oreochromis tanganicae is one of the most common coastal species found in local fish markets[56]

Other fish

Lake Tanganyika is home to more than 80 species of non-cichlid fish and about 60% of these are endemic.[18][26][61][62]

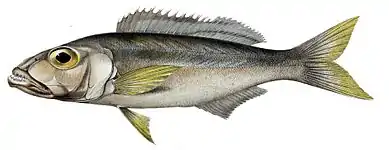

The open waters of the pelagic zone are dominated by four non-cichlid species: Two species of "Tanganyika sardine" (Limnothrissa miodon and Stolothrissa tanganicae) form the largest biomass of fish in this zone, and they are important prey for the forktail lates (Lates microlepis) and sleek lates (L. stappersii).[37] Two additional lates are found in the lake, the Tanganyika lates (L. angustifrons) and bigeye lates (L. mariae), but both these are primarily benthic hunters, although they also may move into open waters.[37] The four lates, all endemic to Tanganyika, have been overfished and larger individuals are rare today.[37]

Among the more unusual fish in the lake are the endemic, facultatively brood parasitic "cuckoo catfish", including at least Synodontis grandiops[63] and S. multipunctatus.[18][38] A number of others are very similar (e.g., S. lucipinnis and S. petricola) and have often been confused; it is unclear if they have a similar behavior.[18][64][65] The facultative brood parasites often lay their eggs synchronously with mouthbroding cichlids. The cichlid pick up the eggs in their mouth as if they were their own. Once the catfish eggs hatch the young eat the cichlid eggs.[18][38] Six catfish genera are entirely restricted to the lake basin: Bathybagrus, Dinotopterus, Lophiobagrus, Phyllonemus, Pseudotanganikallabes and Tanganikallabes.[51][66] Although not endemic on a genus level, six species of Chrysichthys catfish are only found in the Tanganyika basin where they live both in shallow and relatively deep waters;[51] in the latter habitat they are the primary predators and scavengers.[19] A unique evolutionary radiation in the lake is the 15 species of Mastacembelus spiny eels, all but one endemic to its basin.[61][67] Although other African Great Lakes have Synodontis catfish, endemic catfish genera and Mastacembelus spiny eels, the relatively high diversity is unique to Tanganyika, which likely is related to its old age.[67]

Among the non-endemic fish, some are widespread African species but several are only shared with the Malagarasi and Congo River basins, such as the Congo bichir (Polypterus congicus), goliath tigerfish (Hydrocynus goliath), Citharinus citharus, six-banded distichodus (Distichodus sexfasciatus) and mbu puffer (Tetraodon mbu).[51]

Molluscs and crustaceans

A total of 83 freshwater snail species (65 endemic) and 11 bivalve species (8 endemic) are known from the lake.[68] Among the endemic bivalves are three monotypic genera: Grandidieria burtoni, Pseudospatha tanganyicensis and Brazzaea anceyi.[68] Many of the snails are unusual for species living in freshwater in having noticeably thickened shells and/or distinct sculpture, features more commonly seen in marine snails. They are referred to as thalassoids, which can be translated to "marine-like".[69] All the Tanganyika thalassoids, which are part of Prosobranchia, are endemic to the lake.[69] Initially they were believed to be related to similar marine snails, but they are now known to be unrelated. Their appearance is now believed to be the result of the highly diverse habitats in Lake Tanganyika and evolutionary pressure from snail-eating fish and, in particular, Platythelphusa crabs.[26][69][70] A total of 17 freshwater snail genera are endemic to the lake, such as Hirthia, Lavigeria, Paramelania, Reymondia, Spekia, Stanleya, Tanganyicia and Tiphobia.[69] There are about 30 species of non-thalassoid snails in the lake, but only five of these are endemic, including Ferrissia tanganyicensis and Neothauma tanganyicense.[69] The latter is the largest Tanganyika snail and its shell is often used by small shell-dwelling cichlids.[71]

Crustaceans are also highly diverse in Tanganyika with more than 200 species, of which more than half are endemic.[26] They include 10 species of freshwater crabs (9 Platythelphusa and Potamonautes platynotus; all endemic),[72] at least 11 species of small atyid shrimp (Atyella, Caridella and Limnocaridina),[73] an endemic palaemonid shrimp (Macrobrachium moorei),[74] about 100 ostracods,[75] including many endemics,[76][77] and several copepods.[78] Among these, Limnocaridina iridinae lives inside the mantle cavity of the unionid mussel Pleiodon spekei, making it one of only two known commensal species of freshwater shrimp (the other is the sponge-living Caridina spongicola from Lake Towuti, Indonesia).[79][80]

Among Rift Valley lakes, Lake Tanganyika far surpasses all others in terms of crustacean and freshwater snail richness (both in total number of species and number of endemics).[81] For example, the only other Rift Valley lake with endemic freshwater crabs are Lake Kivu and Lake Victoria with two species each.[82][83]

Other invertebrates

The diversity of other invertebrate groups in Lake Tanganyika is often not well-known, but there are at least 20 described species of leeches (12 endemics),[84] 9 sponges (7 endemic), 6 bryozoa (2 endemic), 11 flatworms (7 endemic), 20 nematodes (7 endemic), 28 annelids (17 endemic)[26] and the small hydrozoan jellyfish Limnocnida tanganyicae.[85]

Fishing

Lake Tanganyika supports a major fishery, which, depending on source, provides 25–40%[86] or c. 60% of the animal protein in the diet of the people living in the region.[15][87] Currently, there are around 100,000 people directly involved in the fisheries operating from almost 800 sites. The lake is also vital to the estimated 10 million people living in the greater basin.

Lake Tanganyika fish can be found exported throughout East Africa. Major commercial fishing began in the mid-1950s and has, together with global warming (limiting the habitat of temperature sensitive species), had a heavy impact on the fish populations, causing significant declines.[15][87] In 2016, it was estimated that the total catch was up to 200,000 tonnes.[15] Former industrial fisheries, which boomed in the 1980s, have subsequently collapsed.

Transport

Two ferries carry passengers and cargo along the eastern shore of the lake: MV Liemba between Kigoma and Mpulungu and MV Mwongozo between Kigoma and Bujumbura.

- The port town of Kigoma is the railhead for the railway from Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

- The port town of Kalemie (previously named Albertville) is the railhead for the D.R. Congo rail network.

- The port town of Mpulungu is a proposed railhead for Zambia.[88]

On Dec. 12, 2014, the ferry MV Mutambala capsized on Lake Tanganyika, and more than 120 lives were lost.[89]

History

It is thought that early Homo sapiens were making an impact on the region during the stone age. The time period of the Middle Stone Age to Late Stone Age is described as an age of advanced hunter-gatherers. It is believed they would have caused megafaunal extinctions.[90]

There are many methods in which the native people of the area were fishing. Most of them included using a lantern as a lure for fish that are attracted to light. There were three basic forms. One called Lusenga which is a wide net used by one person from a canoe. The second one is using a lift net. This was done by dropping a net deep below the boat using two parallel canoes and then simultaneously pulling it up. The third is called Chiromila which consisted of three canoes. One canoe was stationary with a lantern while another canoe holds one end of the net and the other circles the stationary one to meet up with the net.[91]

The first known Westerners to find the lake were the British explorers Richard Burton and John Speke, in 1858. They located it while searching for the source of the Nile River. Speke continued and found the actual source, Lake Victoria. Later David Livingstone passed by the lake. He noted the name "Liemba" for its southern part, a word probably from the Fipa language, and in 1927 this was chosen as the new name for the conquered German First World War ship Graf von Götzen which is still serving the lake up to the present time.[92]

World War I

The lake was the scene of two celebrated battles during World War I.

With the aid of the Graf Goetzen (named after Count Gustav Adolf Graf von Götzen, the former governor of German East Africa), the Germans had complete control of the lake in the early stages of the war. The ship was used both to ferry cargo and personnel across the lake, and as a base from which to launch surprise attacks on Allied troops.[93]

It therefore became essential for the Allied forces to gain control of the lake themselves. Under the command of Lieutenant Commander Geoffrey Spicer-Simson the British Royal Navy achieved the monumental task of bringing two armed motor boats HMS Mimi and HMS Toutou from England to the lake by rail, road and river to Albertville (since renamed Kalemie in 1971) on the western shore of Lake Tanganyika. The two boats waited until December 1915, and mounted a surprise attack on the Germans, with the capture of the gunboat Kingani. Another German vessel, the Hedwig, was sunk in February 1916, leaving the Götzen as the only German vessel remaining to control the lake.[93]

As a result of their strengthened position on the lake, the Allies started advancing towards Kigoma by land, and the Belgians established an airbase on the western shore at Albertville. It was from there, in June 1916, that they launched a bombing raid on German positions in and around Kigoma. It is unclear whether or not the Götzen was hit (the Belgians claimed to have hit it but the Germans denied this), but German morale suffered and the ship was subsequently stripped of its gun since it was needed elsewhere.[93]

The war on the lake had reached a stalemate by this stage, with both sides refusing to mount attacks. However, the war on land was progressing, largely to the advantage of the Allies, who cut off the railway link in July 1916 and threatened to isolate Kigoma completely. This led the German commander, Gustav Zimmer, to abandon the town and head south. In order to avoid his prize ship falling into Allied hands, Zimmer scuttled the vessel on July 26, 1916. The vessel was later raised in 1924 and renamed MV Liemba (see transport).[93]

Che Guevara

In 1965 Argentinian revolutionary Che Guevara used the western shores of Lake Tanganyika as a training camp for guerrilla forces in the Congo. From his camp, Che and his forces attempted to overthrow the government, but ended up pulling out in less than a year, as the National Security Agency (NSA) had been monitoring him the entire time and the NSA aided government forces in ambushing his guerrillas.

Recent history

In 1992 Lake Tanganyika featured in the British TV documentary series Pole to Pole. The BBC documentarian Michael Palin stayed on board the MV Liemba and travelled across the lake.

Since 2004 the lake has been the focus of a massive Water and Nature Initiative by the IUCN. The project is scheduled to take five years at a total cost of US$27 million. The initiative is attempting to monitor the resources and state of the lake, set common criteria for acceptable level of sediments, pollution, and water quality in general, and design and establish a lake basin management authority.

Effects of global warming

Because of increasing global temperature there is a direct correlation to lower productivity in Lake Tanganyika.[14] Southern winds create upwells of deep nutrient-rich water on the southern end of the lake. This happens during the cooler months (May to September). These nutrients that are in deep water are vital in maintaining the aquatic food web. The southerly winds are slowing down which limits the ability for the mixing of nutrients. This is correlating with less productivity in the lake.

Alleged Fijian connection

According to a legend of the indigenous people from some parts of the Fiji islands in the South Pacific Ocean, the Fijians originated from Tanganyika. This myth is thought to have originated in relatively recent decades.[94] However, this hypothesis is not tenable and is contradicted by archaeological, linguistic and genetic evidence.

See also

References

- Yohannes, Okbazghi (2008). Water resources and inter-riparian relations in the Nile basin. SUNY Press. p. 127.

- "LAKE TANGANYIKA". www.ilec.or.jp. Archived from the original on 2008-03-28. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- "Tanganyika". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Lake Tanganyika". www.zambiatourism.com. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- Lewis, R. (16 May 2010). "Brown Geologists Show Unprecedented Warming in Lake Tanganyika". Brown University. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- Stanley, H.M., 1899, Through the Dark Continent, London: G. Newnes, Vol. One ISBN 0486256677, Vol. Two ISBN 0486256685

- "Datbase Summary: Lake Tanganyika". www.ilec.or.jp. Archived from the original on 1999-11-10. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- Kullander, S.O.; T.R. Roberts (2011). "Out of Lake Tanganyika: endemic lake fishes inhabit rapids of the Lukuga River". Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwaters. 22 (4): 355–376.

- Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. 366–367. ISBN 978-0-89577-087-5.

- Lévêqu, Christian (1997). Biodiversity Dynamics and Conservation: The Freshwater Fish of Tropical Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 110.

- Cohen; Soreghan; Scholz (1993). "Estimating the age of formation of lakes: An example from Lake Tanganyika, East African Rift system". Geosciences. 21 (6): 511–514. Bibcode:1993Geo....21..511C. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1993)021<0511:ETAOFO>2.3.CO;2.

- De, Wever; Muylaert; der Gucht, Van; Pirlot; Cocquyt; Descy; Plisnier; Vyverman (2005). "Bacterial Community Composition in Lake Tanganyika: Vertical and Horizontal Heterogeneity". Appl Environ Microbiol. 71 (9): 5029–5037. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.9.5029-5037.2005. PMC 1214687. PMID 16151083.

- Edmond; Stallard; Craigh; Weiss; Coulter (1993). "Nutrient chemistry of the water column of Lake Tanganyika". Limnol. Oceanogr. 38 (4): 725–738. Bibcode:1993LimOc..38..725E. doi:10.4319/lo.1993.38.4.0725.

- O'Reilly, Catherine M.; Alin, Simone R.; Plisnier, Pierre-Denis; Cohen, Andrew S.; Mckee, Brent A. (August 14, 2003). "Climate change decreases aquatic ecosystem productivity of Lake Tanganyika, Africa". Nature. 424 (6950): 766–768. Bibcode:2003Natur.424..766O. doi:10.1038/nature01833. PMID 12917682. S2CID 1637315.

- Jensen, M.R. (8 August 2016). "Lake Tanganyika Fisheries Declining From Global Warming". University of Arizona. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Lowe-McConnell, R.H. (2003). "Recent research in the African Great Lakes: Fisheries, biodiversity and cichlid evolution". Freshwater Forum. 20 (1): 4–64.

- Hutter; Yongqi; and Chubarenko (2011). Physics of Lakes, volume 1: Foundation of the Mathematical and Physical Background. P. 11. ISBN 978-3-642-15178-1.

- Wright, J.J.; and L.M. Page (2006). Taxonomic revision of Lake Tanganyikan Synodontis (Siluriformes: Mochokidae). Florida Mus. Nat. Hist. Bull. 46(4): 99–154.

- Lowe-McConnell, R.H. (1987). Ecological Studies in Tropical Fish Communities. ISBN 0-521-28064-8.

- Ryan, Emily; Todd, Jonathan A.; McGlue, Michael; Kimirei, Ismael; Soreghan, Michael (2017). "Variation in Taphonomic Character of Shell Beds in Lake Tanganyika, Africa: Paleoenvironmental and Stratigraphic Implications of Shell Beds in Lakes". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. Geological Society of America. doi:10.1130/abs/2017am-304608. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Spawls, Howell, Drewes, and Ashe (2002). A Field Guide to the Reptiles of East Africa. Academic Press, London. ISBN 0-12-656470-1.

- O'Shea, M. (2003). Zambia & Tanzania. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- Dierkesa; Taborskya; Kohler (1999). "Reproductive parasitism of broodcare helpers in a cooperatively breeding fish". Behavioral Ecology. 10 (5): 510–515. doi:10.1093/beheco/10.5.510.

- Balshine-Earn; Lotem (1998). "Individual recognition in a cooperatively breeding cichlid : Evidence from video playback experiments". Behaviour. 135 (3): 369–386. doi:10.1163/156853998793066221.

- Wernera; Balshineb; Leachc; Lotem (2003). "Helping opportunities and space segregation in cooperatively breeding cichlids". Behavioral Ecology. 14 (6): 749–756. doi:10.1093/beheco/arg067.

- West, K. (prepared by) (2001). Lake Tanganyika: Results and Experiences of the UNDP/GEF Conservation Initiative (RAF/92/G32) in Burundi, D.R. Congo, Tanzania, and Zambia. Lake Tanganyika Biodiversity Project.

- Mortiff, C: Lake Tanganyika and its Diverse Cichlids. Cichlid-Forum. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Takahashi, T.; Hori, M. (2012). "Genetic and Morphological Evidence Implies Existence of Two Sympatric Species in Cyathopharynx furcifer (Teleostei: Cichlidae) from Lake Tanganyika". International Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2012: 980879. doi:10.1155/2012/980879. PMC 3363988. PMID 22675655.

- Kornfield, Ivy; Smith, Peter A (2000). "African Cichlid Fishes: Model Systems for Evolutionary Biology". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 31: 163–196. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.163.

- Meyer, Matchiner, Salburger, Britta, Michael, Walter (25 November 2013). "A tribal level phylogeny of Lake Tanganyika cichlid fishes based on a genomic multi-marker approach". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 83: 56–71. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.10.009. PMC 4334724. PMID 25433288.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Turner, Seehausen; Knight, Allender; Robinson (2001). "How many species of cichlid fishes are there in African lakes?". Molecular Ecology. 10 (3): 793–806. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01200.x. PMID 11298988. S2CID 12925712.

- Seehausen, O. (2015). "Process and pattern in cichlid radiations – inferences for understanding unusually high rates of evolutionary diversification". New Phytologist. 207 (2): 304–312. doi:10.1111/nph.13450. PMID 25983053.

- Nishida, M (1991). "Lake Tanganyika as an evolutionary reservoir of old lineages of East African cichlid fishes: Inferences from allozyme data". Experientia. 47 (9): 974–979. doi:10.1007/bf01929896. S2CID 37599331.

- Sparks; Smith (2004). "Phylogeny and biogeography of cichlid fishes (Teleostei: Perciformes: Cichlidae)". Cladistics. 20 (6): 501–517. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.595.2118. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2004.00038.x. S2CID 36086310.

- Kirchberger; Sefc; Sturmbauer; Koblmuller (2012). "Evolutionary History of Lake Tanganyika's Predatory Deepwater Cichlids". International Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2012: 716209. doi:10.1155/2012/716209. PMC 3362839. PMID 22675652.

- Loiselle, Paul (1994). The Cichlid Aquarium, p. 304. Tetra Press, Germany. ISBN 978-1564651464.

- Lindqvist, O.V.; H. Mölsä; K. Solonen; J. Sarvala, editors (1999). From Limnology to Fisheries: Lake Tanganyika and Other Large Lakes. pp. 213–214. Springer. ISBN 978-0792360179

- Schliewen, U. (1992). Aquarium Fish. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 978-0812013504.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Neolamprologus multifasciatus" in FishBase. March 2017 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Neolamprologus similis" in FishBase. March 2017 version.

- "The 10 biggest cichlids". Practical Fishkeeping. 13 June 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "tanganyika biotope aquarium". Aquariums Life. 2010-02-10. Archived from the original on 2012-03-02. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- Meyer, Matchiner, and Salburger (2015). "Lake Tanganyika—A 'Melting Pot' of Ancient and Young Cichlid Lineages (Teleostei: Cichlidae)?". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0125043. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1025043W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125043. PMC 4415804. PMID 25928886.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Weiss, Cotterill, and Schliewen (2015). "A tribal level phylogeny of Lake Tanganyika cichlid fishes based on a genomic multi-marker approach". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 83: 56–71. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.10.009. PMC 4334724. PMID 25433288.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Takahashi, T. (2008). "Description of a new cichlid fish species of the genus Benthochromis (Perciformes: Cichlidae) from Lake Tanganyika". Journal of Fish Biology. 72 (3): 603–613. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01727.x.

- Takahashi, T.; Nakaya, K. (2003). "New species of Cyphotilapia (Perciformes: Cichlidae) from Lake Tanganyika, Africa". Copeia. 2003 (4): 824–832. doi:10.1643/ia03-148.1. S2CID 83854866.

- Bigirimana, C. (2006). "Cyprichromis microlepidotus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2006. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Smith, M.P. (1998). Lake Tanganyikan Cichlids, pp. 9-10. ISBN 0-7641-0615-5

- SeriouslyFish: Ophthalmotilapia nasuta. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Eretmodus cyanostictus" in FishBase. April 2017 version.

- FishBase: Species in Tanganyika. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- Lowe-McConnell, R (2009). "Fisheries and cichlid evolution in the African Great Lakes: progress and problems". Freshwater Reviews. 2 (2): 131–151. doi:10.1608/frj-2.2.2. S2CID 54011001.

- SeriouslyFish: Julidochromis marlieri. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Bigirimana, C. (2006). "Gnathochromis premaxillaris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2006. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Stewart, T.A.; Albertson, R.C. (2010). "Evolution of a unique predatory feeding apparatus: functional anatomy, development and a genetic locus for jaw laterality in Lake Tanganyika scale-eating cichlids". BMC Biology. 8 (1): 8. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-8. PMC 2828976. PMID 20102595.

- Ntakimazi, G. (2006). "Oreochromis tanganicae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2006. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Begon, M.; and A.H. Fitter (1995). Advances in Ecological Research, vol. 26, p. 203. ISBN 0-12-013926-X

- Salzburger; Niederstätter; Brandstätter; Berger; Parson; Snoeks; Sturmbauer (2006). "Colour-assortative mating among populations of Tropheus moorii, a cichlid fish from Lake Tanganyika, East Africa". Proc Biol Sci. 273 (1584): 257–266. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3321. PMC 1560039. PMID 16543167.

- Toman, R. (1995). Tropheus Evolution In Lake Tanganyika. Cichlidworld. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). Species of Lamprichthys in FishBase. March 2017 version.

- Brown; Britz; Bills; Rüber; Day (2011). "Pectoral fin loss in the Mastacembelidae: a new species from Lake Tanganyika". Journal of Zoology. 284 (4): 286–293. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00804.x.

- Wright, J.J.; Bailey, R.M. (2012). "Systematic revision of the formerly monotypic genus Tanganikallabes (Siluriformes: Clariidae)" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 165 (1): 121–142. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00789.x.

- PlanetCatfish: Synodontis grandiops. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- PlanetCatfish: Synodontis lucipinnis. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- PlanetCatfish: Synodontis petricola. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Wright, J.J. (2017). "A new diminutive genus and species of catfish from Lake Tanganyika (Siluriformes: Clariidae)". J Fish Biol. 91 (3): 789–805. doi:10.1111/jfb.13374. PMID 28744868.

- Brown; Rüber; Bills; Day (2010). "Mastacembelid eels support Lake Tanganyika as an evolutionary hotspot of diversification". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10: 188. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-188. PMC 2903574. PMID 20565906.

- Seddon, M.; Appleton, C.; Van Damme, D.; Graf, D. (2011). Darwall, W.; Smith, K.; Allen, D.; Holland, R.; Harrison, I.; Brooks, E. (eds.). Freshwater molluscs of Africa: diversity, distribution, and conservation. The Diversity of Life in African Freshwaters: Under Water, Under Threat. An Analysis of the Status and Distribution of Freshwater Species Throughout Mainland Africa. IUCN. pp. 92–119. ISBN 978-2831713458.

- Brown, D. (1994). Freshwater Snails Of Africa And Their Medical Importance. 2nd edition. ISBN 0-7484-0026-5

- West, K.; Cohen, A. (1996). "Shell microstructure of gastropods from Lake Tanganyika, Africa: adaptation, convergent evolution, and escalation". Evolution. 50 (2): 672–682. doi:10.2307/2410840. JSTOR 2410840. PMID 28568935.

- Koblmüller; Duftner; Sefc; Aibara; Stipacek; Blanc; Egger; Sturmbauer (2007). "Reticulate phylogeny of gastropod-shell-breeding cichlids from Lake Tanganyika — the result of repeated introgressive hybridization". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 7. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-7. PMC 1790888. PMID 17254340.

- Marijnissen; Michel; Daniels; Erpenbeck; Menken; Schram (2006). "Molecular evidence for recent divergence of Lake Tanganyika endemic crabs (Decapoda: Platythelphusidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 40 (2): 628–634. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.03.025. PMID 16647274.

- Fryer, G (2006). "Evolution in ancient lakes: radiation of Tanganyikan atyid prawns and speciation of pelagic cichlid fishes in Lake Malawi". Hydrobiologia. 568 (1): 131–142. doi:10.1007/s10750-006-0322-x. S2CID 44127332.

- De Grave, S. (2013). "Macrobrachium moorei". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- Martens; Schön; Meisch; Horne (2008). "Global diversity of ostracods (Ostracoda, Crustacea) in freshwater". Hydrobiologia. 595: 185–193. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9245-4. S2CID 207150861.

- Gitter, F.; Gross, M.; Piller, W.E. (2015). "Sub-Decadal Resolution in Sediments of Late Miocene Lake Pannon Reveals Speciation of Cyprideis (Crustacea, Ostracoda)". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0109360. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1009360G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109360. PMC 4406499. PMID 25902063.

- Schön, I.; Martens, K. (2012). "Molecular analyses of ostracod flocks from Lake Baikal and Lake Tanganyika". Hydrobiologia. 682 (1): 91–110. doi:10.1007/s10750-011-0935-6. S2CID 14831643.

- Cirhuza, D.M.; Plisnier, P.-D. (2016). "Composition and seasonal variations in abundance of Copepod (Crustacea) populations from the northern part of Lake Tanganyika". Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management. 19 (4): 401–410. doi:10.1080/14634988.2016.1251277. S2CID 90502032.

- De Grave, S.; Cai, Y.; Amnker, A. (2008). "Global diversity of shrimps (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea) in freshwater". Hydrobiologia. 595: 287–293. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9024-2. S2CID 22945163.

- De Grave, S. (2013). "Limnocaridina iridinae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Segers, H.; and Martens, K; editors (2005). The Diversity of Aquatic Ecosystems. p. 46. Developments in Hydrobiology. Aquatic Biodiversity. ISBN 1-4020-3745-7

- Cumberlidge, N.; and Meyer, K. S. (2011). A revision of the freshwater crabs of Lake Kivu, East Africa. Journal Articles. Paper 30.

- Cumberlidge, N.; Clark, P.F. (2017). "Description of three new species of Potamonautes MacLeay, 1838 from the Lake Victoria region in southern Uganda, East Africa (Brachyura: Potamoidea: Potamonautidae)". European Journal of Taxonomy. 371 (371): 1–19. doi:10.5852/ejt.2017.371.

- Segers, H.; and Martens, K; editors (2005). The Diversity of Aquatic Ecosystems. p. 44. Developments in Hydrobiology. Aquatic Biodiversity. ISBN 1-4020-3745-7

- Salonen; Högmander; Langenberg; Mölsä; Sarvala; Tarvainen; and Tiirola (2012). Limnocnida tanganyicae medusae (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa): a semiautonomous microcosm in the food web of Lake Tanganyika. Hydrobiologia 690(1): 97–112.

- "Global warming is killing off tropical lake fish – Study of Lake Tanganyika". www.mongabay.com. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- McGrath, M. (8 August 2016). "Decline of fishing in Lake Tanganyika 'due to warming'". BBC. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- "Railways Africa – Extending beyond Chipata". railwaysafrica.com. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- "DR Congo: Many dead after ferry sinks on Lake Tanganyika". BBC News. 2014-12-14. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- East African Ecosystems and Their Conservation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lake Tanganyika and Its Life. Oxford Press. 1991.

- David Livingstone (2008). The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa from 1865 to His Death. 1. BiblioBazaar. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-554-26021-1.

- Giles Foden: Mimi and Toutou Go Forth — The Bizarre Battle for Lake Tanganyika, Penguin, 2004.

- Eräsaari, Matti (2015). "The iTaukei Chief: Value and Alterity in Verata". Journal de la Société des Océanistes (141): 239–254. doi:10.4000/jso.7407. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lake Tanganyika. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lake Tanganyika. |

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- Index of Lake Tanganyika Cichlids

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Tanganyika". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- "Tanganyika". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Tanganyika". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- A Trans-Africa Inland Waterway System?

- Democratic Republic of Congo Waterways Assessment