Lake Malawi

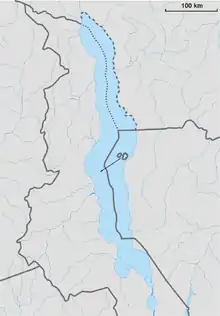

Lake Malawi, also known as Lake Nyasa in Tanzania and Lago Niassa in Mozambique, is an African Great Lake and the southernmost lake in the East African Rift system, located between Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania.

| Lake Malawi (Lake Nyasa) | |

|---|---|

View from orbit North is in upper right corner | |

Lake Malawi (Lake Nyasa) | |

| Coordinates | 12°11′S 34°22′E |

| Lake type | Ancient lake, Rift lake |

| Primary inflows | Ruhuhu River[1] |

| Primary outflows | Shire River[1] |

| Basin countries | Malawi, Mozambique, and Tanzania |

| Max. length | 560 km (350 mi)[1] to 580[2] |

| Max. width | 75 km (47 mi)[1] |

| Surface area | 29,600 km2 (11,400 sq mi)[1] |

| Average depth | 292 m (958 ft)[3] |

| Max. depth | 706 m (2,316 ft)[3] |

| Water volume | 8,400 km3 (2,000 cu mi)[3] |

| Surface elevation | 468 metres (1,535 ft) above sea level[4] |

| Islands | Likoma and Chizumulu islets |

| References | [1][3] |

| Official name | Lake Niassa and its Coastal Zone |

| Designated | 26 April 2011 |

| Reference no. | 1964[5] |

It is the fifth largest fresh water lake in the world by volume, the ninth largest lake in the world by area—and the third largest and second deepest lake in Africa. Lake Malawi is home to more species of fish than any other lake,[6] including at least 700 species of cichlids.[7] The Mozambique portion of the lake was officially declared a reserve by the Government of Mozambique on June 10, 2011,[8] while in Malawi a portion of the lake is included in Lake Malawi National Park.[6]

Lake Malawi is a meromictic lake, meaning that its water layers do not mix. The permanent stratification of Lake Malawi's water and the oxic-anoxic boundary (relating to oxygen in the water) are maintained by moderately small chemical and thermal gradients.[9]

Geography

Lake Malawi is between 560 kilometres (350 mi)[1] and 580 kilometres (360 mi) long,[2] and about 75 kilometres (47 mi) wide at its widest point. The lake has a total surface area of about 29,600 square kilometres (11,400 sq mi).[1] The lake is 706 m (2,316 ft) at its deepest point, located in a major depression in the north-central part.[10] Another smaller depression in the far north reaches a depth of 528 m (1,732 ft).[10] The southern half of the lake is shallower; less than 400 m (1,300 ft) in the south-central part and less than 200 m (660 ft) in the far south.[10] The lake has shorelines on western Mozambique, eastern Malawi, and southern Tanzania. The largest river flowing into it is the Ruhuhu River, and there is an outlet at its southern end, the Shire River, a tributary that flows into the very large Zambezi River in Mozambique.[2] Evaporation accounts for more than 80% of the water loss from the lake, considerably more than the outflowing Shire River.[11] The outflows from Lake Malawi into the Shire River are vital for the economy as the water resources support hydropower, irrigation and downstream biodiversity.[12] Concerns have been raised over the future climate change impacts of Lake Malawi due to the recent decline in lake levels and the overall drying trend.[13] The climate in the lake region is already experiencing changes, with the temperatures predicted to increase throughout the country.[14]

The lake is about 350 kilometres (220 mi) southeast of Lake Tanganyika, another of the great lakes of the East African Rift.

The Lake Malawi National Park is located at the southern end of the lake.[15]

Lake Malawi (1967)

Lake Malawi (1967) Mwaya Beach

Mwaya Beach Beach at Cape Maclear near Monkey Bay

Beach at Cape Maclear near Monkey Bay

Geological history

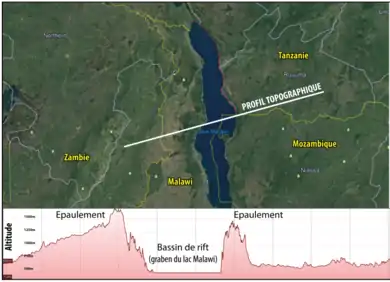

Malawi is one of the major Rift Valley lakes and an ancient lake. The lake lies in a valley formed by the opening of the East African Rift, where the African tectonic plate is being split into two pieces. This is called a divergent plate tectonics boundary. Malawi has typically been estimated to be 1–2 million years old (mya),[16][17] but more recent evidence points to a considerably older lake with a basin that started to form about 8.6 mya and deep-water condition first appeared 4.5 mya.[18][19]

The water levels have varied dramatically over time, ranging from almost 600 m (2,000 ft) below current level[20] to 10–20 m (33–66 ft) above.[18] During periods the lake dried out almost completely, leaving only one or two relatively small, highly alkaline and saline lakes in what currently are Malawi's deepest parts.[18][20] A water chemistry resembling the current conditions only appeared about 60,000 years ago.[20] Major low-water periods are estimated to have occurred about 1.6 to 1.0–0.57 million years ago (where it might have dried out completely), 420,000 to 250,000–110,000 years ago,[18] about 25,000 years ago and 18,000–10,700 years ago.[19] During the peak of the low-water period between 1390 and 1860 AD, it may have been 120–150 m (390–490 ft) below current water levels.[17]

Water characteristics

The lake's water is alkaline (pH 7.7–8.6) and warm with a typical surface temperature between 24 and 29 °C (75–84 °F), while deep sections typically are about 22 °C (72 °F).[21] The thermocline is located at a depth of 40–100 m (130–330 ft).[11] The oxygen limit is at a depth of approximately 250 m (820 ft), effectively restricting fish and other aerobic organisms to the upper part.[22] The water is very clear for a lake and the visibility can be up to 20 m (66 ft), but slightly less than half this figure is more common and it is below 3 m (10 ft) in muddy bays.[10] However, during the rainy season months of January to March, the waters are more muddy due to muddy river inflows.[23]

European discovery and colonisation

The Portuguese trader Candido José da Costa Cardoso was the first European to visit the lake in 1846.[24] David Livingstone reached the lake in 1859, and named it Lake Nyasa.[2] He also referred to it by a pair of nicknames: Lake of Stars and Lake of Storms.[25] The Lake of Stars nickname came after Livingstone observed lights from the lanterns of the fishermen in Malawi on their boats, that resemble, from a distance, stars in the sky.[26] Later, after experiencing the unpredictable and extremely violent gales that sweep through the area he also referred to it as the Lake of Storms.[26]

On 16 August 1914, Lake Malawi was the scene of a brief naval battle when the British gunboat SS Gwendolen, commanded by a Captain Rhoades, heard that World War I had broken out, and he received orders from the British Empire's high command to "sink, burn, or destroy" the German Empire's only gunboat on the lake, the Hermann von Wissmann, commanded by a Captain Berndt. Rhoades's crew found the Hermann von Wissmann in a bay near Sphinxhaven, in German East African territorial waters. Gwendolen disabled the German boat with a single cannon shot from a range of about 1,800 metres (2,000 yd). This very brief gunboat conflict was hailed by The Times in England as the British Empire's first naval victory of World War I.[27][28]

Borders

Tanzania–Malawi dispute

The partition of the lake's surface area between Malawi and Tanzania is under dispute. Tanzania claims that the international border runs through the middle of the lake.[29] On the other hand, Malawi claims the whole of the surface of this lake that is not in Mozambique, including the waters that are next to the shoreline of Tanzania.[30] Both sides cite the Heligoland Treaty of 1890 between Great Britain and Germany concerning the border. The wrangle in this dispute occurred when the British colonial government, just after they had captured Tanganyika from Germany, placed all of the waters of the lake under a single jurisdiction, that of the territory of Nyasaland, without a separate administration for the Tanganyikan portion of the surface. Later in colonial times, two jurisdictions were established.[31]

The dispute came to a head in 1967 when Tanzania officially protested to Malawi; however nothing was settled.[32] Occasional flare-ups of conflict occurred during the 1990s and in the 21st century.[33] In 2012, Malawi's oil exploration initiative brought the issue to the fore, with Tanzania demanding that exploration cease until the dispute was settled.[34]

Malawi–Mozambique border

In 1954, an agreement was signed between the British and the Portuguese making the middle of the lake their boundary with the exception of Chizumulu Island and Likoma Island, which were kept by the British and are now part of Malawi.[31]

Transport

MV Chauncy Maples began service on the lake in 1901 as the SS Chauncy Maples: a floating clinic and church for the Universities' Mission to Central Africa. She later served as a ferry and is currently being renovated into a mobile clinic at Monkey Bay. The renovation was expected to be complete during the first half of 2014, but was halted in 2017.[35] MV Mpasa entered service in 1935.[36] The ferry MV Ilala entered service in 1951. In recent years she has often been out of service, but when operational she runs between Monkey Bay at the southern end of the lake to Karonga on the northern end, and occasionally to the Iringa Region of Tanzania. The ferry MV Mtendere entered service in 1980.[36] By 1982 she was carrying 100,000 passengers each year.,[36] but as of 2014 she was out of service.[37] She normally serves the southern part of the lake but if Ilala was out of service she operated the route to Karonga. The Tanzanian ferry MV Songea was built in 1988.[38] Her operator was the Tanzania Railway Corporation Marine Division until 1997, when it became the Marine Services Company Limited.[39] Songea plies weekly between Liuli and Nkhata Bay via Itungi and Mbamba Bay.[38]

Wildlife

Wildlife found in and around Lake Malawi or Nyasa includes Nile crocodiles, hippopotamus, monkeys,[40] and a significant population of African fish eagles that feed off fish from the lake.[41]

Fishing

Lake Malawi has for millennia provided a major food source to the residents of its shores since its waters are rich in fish. Among the most popular are the four species of chambo, consisting of any one of four species in the subgenus Nyasalapia (Oreochromis karongae, O. lidole, O. saka and O. squamipinnis), as well as the closely related O. shiranus.[42] Other species that support important fisheries include the Lake Malawi sardine (Engraulicypris sardella) and the large kampango catfish (Bagrus meridionalis).[10] Most fishing provides food for the increasing human population near the lake, but some are exported from Malawi. The wild population of fish is increasingly threatened by overfishing and water pollution.[43][44] A drop in the lake's water level represents another threat, and is believed to be driven by water extraction by the increasing human population, climate change and deforestation.[44] The chambo and kampango have been particularly overfished (the kampango declined by about 90% from 2006 to 2016,[45] O. karongae and O. squamipinnis by about 94%, and O. lidole might already be extinct[46][47]) and they are now seriously threatened.[48] The IUCN recognises 117 species of Malawi cichlids as threatened; some of these have tiny ranges and may be restricted to rocky coastlines only a few hundred metres long.[49]

1. Diplotaxodon, one of the very few cichlid genera that occurs offshore in relatively deep water.[22]

2. Nimbochromis livingstonii is a piscivorous hap that is famous for playing dead to lure prey close.[10][50][51]

3. As typical of utaka, Copadichromis azureus has bright blue males (shown) and duller females that are silvery with dark spots.[52]

4. Aulonocara stuartgranti is part of a group of relatively peaceful species popularly known as peacock cichlids.[53]

5. Fossorochromis rostratus is an "aberrant" hap that often sifts mouthfuls of sand to extract small food organisms.[10][54]

6. Like many mbuna, Pseudotropheus saulosi is a small cichlid where both male (blue and black) and female (yellow) are colorful.[55]

Cichlids

Lake Malawi is noted for being the site of evolutionary radiations among several groups of animals, most notably cichlid fish.[56] There are at least 700 cichlid species in Lake Malawi,[7] with some estimating that the actual figure is as high as 1,000 species.[8][57] The actual number is labelled with some uncertainty because of the many undescribed species and the extreme variation among some species, making the task of delimiting them very complex.[7][10] Except for four species (Astatotilapia calliptera, Coptodon rendalli, Oreochromis shiranus and Serranochromis robustus), all cichlids in the lake are endemic to the Malawi system, which also includes nearby smaller Lake Malombe and the upper Shire River.[10][58][59] Many of these have become popular among aquarium owners due to their bright colors. Recreating a Lake Malawi biotope to host cichlids became quite popular in the aquarium hobby.[60] Most Malawi cichlids are found in relatively shallow coastal waters,[10] but Diplotaxodon has been recorded down to depths of 200–220 m (660–720 ft) and several (especially Diplotaxodon, Rhamphochromis and Copadichromis quadrimaculatus) are known from pelagic waters.[22]

The cichlids of the lake are divided into two groups and the vast majority of the species are haplochromines. The sister species to the Malawi haplochromines is Astatotilapia sp. Ruaha (a currently undescribed species from Great Ruaha River), and these two separated between 2.13 and 6.76 million years ago (mya).[61] The earliest divergence within the Malawi haplochromines occurred between 1.20 and 4.06 mya,[61] but most radiations in this group are far younger; in extreme cases species may have diverged only a few hundred years ago.[17] The Malawi haplochromines are mouthbrooders, but otherwise vary extensively in general behaviour and ecology.[10] Within the Malawi haplochromines there are two main groups, the haps and the mbuna. The haps (they were formerly included in Haplochromis) can be further subdivided into three subgroups: The relatively large, often more than 20 cm (8 in) long, and aggressive piscivores that roam various habitats in pursuit of prey, the open-water (although often not far from sand or rocks) utaka that feed in schools on zooplankton and typically are of medium size, and finally a subgroup of "aberrant" species that essentially are defined by them not fitting clearly into the other subgroups.[10][51][62] Adult male haps generally display bright colors, while juveniles of both sexes and adult females typically show a silvery or grey coloration with sometimes irregular black bars or other markings.[10][51] The second main haplochromine group are the mbuna, a name used both locally and popularly, which means "rockfish" in Tonga.[63] They are found at rocky outcrops, territorially aggressive (although commonly found in high densities) and often specialised aufwuchs feeders.[10][51] The mbuna species tend to be relatively small, mostly less than 13 cm (5 in) long, and often both sexes are brightly colored with males having egg-shaped yellow spots on their anal fin (a feature particularly prevalent in the mbuna, but not exclusive to this group).[10][51]

The second group, the tilapia, comprises only six species in two genera in Lake Malawi: The redbreast tilapia (Coptodon rendalli), a widespread African species, is the only substrate-spawning cichlid in the lake.[10][64] This large cichlid mainly feeds on macrophytes.[10][65] The remaining are five mouthbrooding species of Oreochromis; four chambo in the subgenus Nyasalapia (O. karongae, O. lidole, O. saka and O. squamipinnis) that are endemic to the Lake Malawi system, as well as the closely related O. shiranus, which also is found in Lake Chilwa.[10][42][58] The Malawi Oreochromis mainly feed on phytoplankton, reach lengths up to 26–42 cm (10–17 in) depending on the exact species, and are mostly black or silvery-gray with relatively indistinct dark bars.[10][58][66] Male chambo have unique genital tassels when breeding, which aid in egg fertilisation in a manner comparable to the egg-spots on the anal fin of haplochromines.[10][42]

Non-cichlids

The vast majority of the fish species in the lake are cichlids. Among the non-cichlid native fish are several species of cyprinids (in genera Barbus, Labeo and Opsaridium, and the Lake Malawi sardine Engraulicypris sardella), airbreathing catfish (Bathyclarias and Clarias, and the kampango Bagrus meridionalis), mochokid catfish (Chiloglanis and Malawi squeaker Synodontis njassae), Mastacembelus spiny eel, mormyrids (Marcusenius, Mormyrops and Petrocephalus), the African tetra Brycinus imberi, the poeciliid Aplocheilichthys johnstoni, the spotted killifish (Nothobranchius orthonotus), and the mottled eel (Anguilla nebulosa).[10]

At a genus level, most of these are widespread in Africa, but Bathyclarias is entirely restricted to the lake.[68]

Molluscs

Lake Malawi is home to 28 species of freshwater snails (including 16 endemics) and 9 bivalves (2 endemics, Aspatharia subreniformis and the unionid Nyassunio nyassaensis).[69][70] The endemic freshwater snails are all members of the genera Bellamya, Bulinus, Gabbiella, Lanistes and Melanoides.[71]

Lake Malawi is home to a total of four snail species in the genus Bulinus, which is a known intermediate host of bilharzia. A survey in Monkey Bay in 1964 found two endemic species of snails of the genus (B. nyassanus and B. succinoides) in the lake, and two non-endemic species (B. globosus and B. forskalli) in lagoons separated from it. The latter species are known intermediate hosts of bilharzia, and larvae of the parasite were detected in water containing these, but in experiments C. Wright of the British Museum of Natural History was unable to infect the two species endemic to the lake with the parasites. The field workers, who spent many hours on and in the lake, did not find either B. globosus or B. forskalli in the lake itself.[72] More recently, the disease has become a problem in the lake itself as the endemic B. nyassanus has become an intermediate host. This change, first noticed in the mid-1980s, is possibly related to a decline in snail-eating cichlids (for example, Trematocranus placodon) due to overfishing and/or a new strain of the bilharzia parasite.[21]

Crustaceans

Unlike Lake Tanganyika with its many endemic freshwater crabs and shrimp, there are few such species in Lake Malawi. The Malawi blue crab, Potamonautes lirrangensis (syn. P. orbitospinus), is the only crab in the lake and it is not endemic.[73][74] The atyid shrimp Caridina malawensis is endemic to the lake, but it is poorly known and has historically been confused with C. nilotica, which is not found in the lake.[75] Pelagic zooplanktonic species include two cladocerans (Diaphanosoma excisum and Bosmina longirostris), three copepods (Tropodiaptomus cunningtoni, Thermocyclops neglectus and Mesocyclops aequatorialis),[76] and several ostracods (including both described and undescribed species).[77]

Lake flies

.jpg.webp)

Lake Malawi is famous for the huge swarms of tiny, harmless lake flies, Chaoborus edulis.[78] These swarms, typically appearing far out over water, can be mistaken for plumes of smoke and were also noticed by David Livingstone when he visited the lake.[78][79][80] The aquatic larvae feed on zooplankton, spending the day at the bottom and the night in the upper water levels.[78] When they pupate they float to the surface and transform into adult flies.[80] The adults are very short-lived and the swarms, which can be several hundred metres tall and often have a spiraling shape, are part of their mating behaviour.[78][81] They lay their eggs at the water's surface and the adults die.[81] The larvae are an important food source for fish,[76][78][82] and the adult flies are important both to birds and local people, who collect them to make kungu cakes/burgers, a local delicacy with a very high protein content.[79][80]

2015 mine leak

In January 2015, a sediment control tank collapsed at the Paladin Energy-owned uranium mine in Northern Malawi after a high intensity rain storm hit the area. It was revealed that approximately 50 litres of non radioactive material leaked into a local creek. Despite reports in local media of radioactive contamination the government conducted independent scientific tests on the local river system and found that there was no effect on the environment despite the contrary reports in some parts of the local media.[83][84]

Swimming

The 25 km solo swim across Lake Malawi between Cape Ngomba and Senga Bay has been accomplished on 5 occasions by 16 swimmers

1992: Lewis Pugh 9hrs 52 minutes (UK/SA)[85] and Otto Thanning (SA) 10hrs 5 minutes

2010: Abigail Brown (UK) 9hrs 45 minutes[86]

2013: Milko van Gool (Netherlands) 8hrs 46 minutes[87] and Kaitlin Harthoorn (US) 9hrs 17 minutes

2016: (current record) Jean Craven (SA), Robert Dunford (Kenya), Michiel Le Roux (SA), Samantha Whelpton (SA), Greig Bannatyne (SA), Haydn Von Maltitz (SA), Douglas Livingstone-Blevins (SA) 7hrs 53 mins [88]

2019: Chris Stapley (Eswatini) and Jay Azran (SA) 8hrs 40 minutes, Andrew Stevens (Australia) 10hrs 50 minutes, and Ruth Azran (SA) 11hrs 8 minutes.[89][90]

In 2019, Martin Hobbs (SA), became the first person to swim the full length of Lake Malawi (54 days), as well as setting the world record for longest solo swim in a lake[91]

References

- "Malawi Cichlids". AC Tropical Fish. Aquaticcommunity.com. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- "Lake Nyasa". Columbia Encyclopedia Online. Columbia University Press. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- "Lake Malawi". World Lakes Database. International Lake Environment Committee Foundation. Archived from the original on February 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. p. 222. ISBN 0-89577-087-3.

- "Lake Niassa and its Coastal Zone". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Protected Areas Programme". United Nations Environment Programme, World Conservation Monitoring Centre, UNESCO. October 1995. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- Turner, Seehausen, Knight, Allender, and Robinson (2001). "How many species of cichlid fishes are there in African lakes?" Molecular Ecology 10: 793–806.

- WWF (10 June 2011). "Mozambique’s Lake Niassa declared reserve and Ramsar site" Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- Pilskaln, C. H. (2004). "Seasonal and Interannual Particle Export in an African Rift Valley Lake: A 5-Yr Record from Lake Malawi, Southern East Africa". Limnology and Oceanography, 49(4), 964–977. {{doi:10.2307/3597647}}.

- Konings, Ad (1990). Ad Konings' Book of Cichlids and all the other Fishes of Lake Malawi. ISBN 978-0866225274.

- Park, L.E.; and A.S. Cohen (2011). Paleoecological response of ostracods to early Late Pleistocene lake-level changes in Lake Malawi, East Africa. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 303: 71–80. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.02.038

- Bhave, A., Vincent, K. and Mkwambisi, D. (2019) Projecting future water availability in Lake Malawi and the Shire River basin, Future Climate for Africa Brief, Cape Town: CDKN. https://futureclimateafrica.org/resource/brief-projecting-future-water-availability-inlake-malawi-and-the-shire-river-basin/%5B%5D

- Bhave, Ajay G.; Bulcock, Lauren; Dessai, Suraje; Conway, Declan; Jewitt, Graham; Dougill, Andrew J.; Kolusu, Seshagiri Rao; Mkwambisi, David (2020-05-01). "Lake Malawi's threshold behaviour: A stakeholder-informed model to simulate sensitivity to climate change". Journal of Hydrology. 584: 124671. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.124671. ISSN 0022-1694.

- Future Climate for Africa, "How can we improve the use of information for a climate-resilient Malawi?", February 2020,https://futureclimateafrica.org/resource/how-can-we-improve-the-use-of-information-for-a-climate-resilient-malawi/

- "Lake Malawi National Park". World Heritage List. UNESCO. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- Wilson, Ab; Teugels, Gg; Meyer, A (Apr 2008). Moritz, Craig (ed.). "Marine Incursion: The Freshwater Herring of Lake Tanganyika Are the Product of a Marine Invasion into West Africa". PLOS ONE. 3 (4): e1979. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.1979W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001979. PMC 2292254. PMID 18431469.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Givnish, T.J.; and K.J. Sytsma, editors (1997). Molecular Evolution and Adaptive Radiation, p. 598. ISBN 0-521-57329-7.

- Delvaux, D. (1995). Age of Lake Malawi (Nyasa) and water level fluctuations. Mus. roy. Afr. centr., Tervuren (Belg.), Dept. Geol. Min., Rapp. ann. 1993 & 1994: 99–108.

- Sturmbauer; Baric; Salzburger; Rüber; and Verheyen (2001). Lake Level Fluctuations Synchronize Genetic Divergences of Cichlid Fishes in African Lakes. Mol Biol Evol 18(2): 144–154. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003788

- Cohen; Stone; Beuning; Park; Reinthal; Dettman; Scholz; Johnson; King; Talbot; Brown; and Ivory (2007). Ecological consequences of early Late Pleistocene megadroughts in tropical Africas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104(42): 16422-16427. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703873104

- Stauffer, J.R.; and H. Madsen (2012). Schistosomiasis in Lake Malawi and the Potential Use of Indigenous Fish for Biological Control. Pp. 119–140 in: Rokni, M.B., editor. Schistosomiasis. ISBN 978-953-307-852-6.

- Lowe-McConnell, R.H. (2003). Recent research in the African Great Lakes: Fisheries, biodiversity and cichlid evolution. Freshwater Forum 20(1): 4–64.

- "What Are The Primary Inflows And Outflows Of Lake Malawi?". WorldAtlas. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- Jeal, Tim (1973). Livingstone. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

- Bayly, Paul (2014-03-27). David Livingstone, Africa's Greatest Explorer: The Man, the Missionary and the Myth. Fonthill Media.

- R. W. McColl (2005). Encyclopedia of World Geography. 1. Infobase Publishing. p. 576.

- Paice, Edward (2007). Tip and Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great War in Africa. p. not cited. ISBN 978-0-297-84709-0.

- "The Guendolen v Hermann Von Wissmann". Clash of Steel.

- "Govt clarifies on Tanzania-Malawi border". Daily News (via KForum). Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. 1 August 2007. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- Kamlomo, Gabriel (27 August 2012). "Malawi optimistic on Tanzania border dispute". The Daily Times. Malawi. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- Mayall, James (1973). "The Malawi-Tanzania Boundary Dispute". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 11 (4): 611–628. doi:10.1017/s0022278x00008776. JSTOR 161618. S2CID 154785268.

- Chitsulo, Kondwani (3 September 2012). "JB Meets Opposition Leaders On Tanzania Again". Malawi Voice. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013.

- Joel, Lawi (15 August 2012). "Tanzania: Life Continues on Lake Nyasa Despite Border Dispute". Daliy News. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

- "Malawi: Old Border Dispute With Tanzania Over Lake Malawi Flares Up Again". Pretoria, South Africa: Institute for Security Studies. 8 August 2012.

- "Chauncy Maples : Lake Malawi's Clinic". Chauncymaples.org. Archived from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- Sefton, John (2010-11-09). "Mtendere". Community Forum. ShipStamps.co.uk.

- Malawi, Face of. "Malawi Shipping Company set to launch new passenger vessel on Lake Malawi – Face Of Malawi".

- "MV. Songea". Vessels. Marine Services Company Limited. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- "Home". Vessels. Marine Services Company Limited. Archived from the original on 10 September 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- "Lake Malawi National Park". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- "Geography & Wildlife Malawi". Our Africa. SOS Children's Villages. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- Turner, G.F.; and N.C. Mwanyama (July 1992).Distribution and Biology of Chambo (Oreochromis spp.) in Lakes Malawi and Malombe. Food and Agriculture Organization, Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, FI:DP/MLW/86/013, Field Document 21. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- "Preserving the Future for Lake Malawi". web.mit.edu. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- Banda, M. (22 May 2013). "Rapid drop in Lake Malawi's water levels drives down fish stocks". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- Phiri, B.; Gobo, E.; Tweddle, D.; Kanyerere, Z. (2019). "Bagrus meridionalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T60856A155041757. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T60856A155041757.en.

- Kanyerere, Z.; Phiri, B.; Shechonge, A. (2018). "Oreochromis karongae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T61293A148647939. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T61293A148647939.en.

- Phiri, B.; Kanyerere, Z. (2018). "Oreochromis squamipinnis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T60760A148648312. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T60760A148648312.en.

- McKenzie, D.; B. Swails (22 May 2013). "Rangers struggle to save endangered fish in Lake Malawi". CNN. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- IUCN Red Lists: Geographic Patterns. Eastern Africa. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- Schliewen, U. (1992). Aquarium Fish. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 978-0812013504.

- Elieson, M: Haps Vs. Mbuna. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- Elieson, M: Copadichromis azureus. CichlidForum. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- Elieson, M: The Peacocks of Lake Malawi. CichlidForum. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- O'Brien, R: Fossorochromis rostratus. CichlidForum. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- Barber, P: Pseudotropheus saulosi. CichlidForum. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- Svardal, Hannes; Quah, Fu Xiang; Malinsky, Milan; Ngatunga, Benjamin P; Miska, Eric A; Salzburger, Walter; Genner, Martin J; Turner, George F; Durbin, Richard (2019-08-18). "Ancestral hybridisation facilitated species diversification in the Lake Malawi cichlid fish adaptive radiation". doi:10.1101/738633. S2CID 202010546. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kornfield, I.; & P.F. Smith (2000). African Cichlid Fishes: Model Systems for Evolutionary Biology. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 31: 163–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.163.

- Oliver, M.K. (12 April 2015). The Tilapias of Lake Malawi. MalawiCichlids. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- Oliver, M.K. (12 April 2015). The Nonendemic Haplochromine Cichlids of Lake Malawi. MalawiCichlids. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- Pardee, Keith. "African Cichlids, Lake Malawi". www.aquariumlife.net. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- Genner; Ngatunga; Mzighani; Smith; and Turner (2015). Geographical ancestry of Lake Malawi’s cichlid fish diversity. Biol. Lett. 11: 2015023. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0232

- Aquaticcommunity (2004–08).Haplochromis. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- Loiselle, P.V. (1988). A Fishkeepers Guide to African Cichlids, p. 97. Salamander Books, London & New York. ISBN 0-86101-407-3.

- Oliver, M.K. (12 April 2015). Coptodon rendalli. Malawicichlids. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Coptodon rendalli" in FishBase. April 2017 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). Species of Oreochromis in FishBase. April 2017 version.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Bagrus meridionalis" in FishBase. April 2017 version.

- Anseaume, L.; and G.G. Teugels (1999). On the rehabilitation of the clariid catfish genus Bathyclarias endemic to the East African Rift Lake Malawi. Fish Biology 55(2): 405–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1999.tb00687.x

- Segers, H.; and Martens, K; editors (2005). The Diversity of Aquatic Ecosystems. p. 46. Developments in Hydrobiology. Aquatic Biodiversity. ISBN 1-4020-3745-7

- Kaunda, E., Magombo, Z., Kahwa, D. & Mailosi, A. (2010). "Aspatharia subreniformis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T44266A10884713. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-3.RLTS.T44266A10884713.en.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Brown, D. (1994). Freshwater Snails Of Africa And Their Medical Importance. p. 571. 2nd edition. ISBN 0-7484-0026-5

- Wright, C. A.; Klein, J.; Eccles, D. H. (1967). "Endemic species of Bulinus (Mollusca: Planorbidae) in Lake Malawi (= Lake Nyasa)". Journal of Zoology. 151 (1): 199–209. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1967.tb02873.x. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- Cumberlidge, N., and Meyer, K. S. (2011). A revision of the freshwater crabs of Lake Kivu, East Africa. Journal Articles. Paper 30.

- Dobson, M. (2004). Freshwater Crabs of Africa. Archived 2016-06-23 at the Wayback Machine Freshwater Forum 21: 3–26.

- Richard, J.; and Clark, P.F. (2009). African Caridina (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea: Atyidae): redescriptions of C. africana Kingsley, 1882, C. togoensis Hilgendorf, 1893, C. natalensis Bouvier, 1925 and C. roubaudi Bouvier, 1925 with descriptions of 14 new species. Zootaxa 1995: 1–75

- Darwall; Allison; Turner; and Irvine (2010). Lake of flies, or lake of fish? A trophic model of Lake Malawi. Ecological Modelling 221: 713–727. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2009.11.001

- Martens, K. (2003). On the evolution of Gomphocythere (Crustacea, Ostracoda) in Lake Nyassa/ Malawi (East Africa), with the description of 5 new species. Hydrobiologia 497(1–2): 121–144. doi:10.1023/A:1025417822555

- Morris, B. (2004). Insects and Human Life, pp. 73–76. ISBN 1-84520-075-6

- van Huis, A.; H. van Gurp; and M. Dicke (2012). The Insect Cookbook: Food for a Sustainable Planet, p. 31. ISBN 978-0-231-16684-3

- Malawi Tourism: Interesting seasonal highlights of Malawi. Archived 2014-08-12 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- Andrew, D. (30 June 2015). What Are These Strange Looking "Clouds"? IFLScience. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- Allison; Irvine; Thompson; and Ngatunga (1996). Diets and food consumption rates of pelagic fish in Lake Malawi, Africa. Freshwater Biology 35(3): 489–515. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.1996.tb01764.x

- "No harm caused by Paladin mine Kayerekera – Malawi govt". Malawi Nyasa Times – Malawi breaking news in Malawi. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- Radioactive pollution of Lake Malawi by Australian uranium company Paladin?.

- "Expeditions, Internal Waters".

- "Lake Malawi Crossing". Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- "Milko Van Gool thought to be fastest male solo swimmer across North Channel". BBC News. 2013-07-30.

- "CROSSING LAKE MALAWI".

- TheCows. "Swimming Cows conquer Lake Malawi in brutal conditions – The Cows". Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- "Cows members conquer Lake Malawi in tough conditions for CHOC". The Witness. 10 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Thom, Liezl (26 April 2019). "Man braves crocodiles, hippos to set world record in 54-day swim across lake". ABC News.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lake Malawi. |

- Mayall, James (December 1973). "The Malawi-Tanzania Boundary Dispute". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 11 (4): 611–628. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00008776. S2CID 154785268.

- Recent study on Lake Malawi water levels reveals drought 100,000 years ago

- "Freshwater Fish Species in Lake Malawi (Nyasa) [Southeast Africa]". Mongabay. Retrieved 9 December 2016.