German East Africa

German East Africa (German: Deutsch-Ostafrika) (GEA) was a German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Mozambique. GEA's area was 994,996 square kilometres (384,170 sq mi),[1][2] which was nearly three times the area of present-day Germany, and double the area of metropolitan Germany then.

German East Africa Deutsch-Ostafrika | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1885-1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Flag

Coats of Arms

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Green: Territory comprising German colony of German East Africa

Dark gray: Other German possessions Darkest gray: German Empire Note: the map depicts the historical extent for German territories on a globe showing 1911 borders | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | German colony | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Bagamoyo (1885–90) Dar es Salaam (1890–1918) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | German (official) Swahili, Arabic, Kirundi, Kinyarwanda, Maa, Kisukuma, Iraqw, Chaga languages | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam, traditional African religion, Christianity (Catholic Church and Lutheranism) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1885–1888 | Wilhelm I | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1888 | Frederick III | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1888–1918 | Wilhelm II | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1885-1891 (first) | Carl Peters | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1912–1918 (last) | Heinrich Schnee | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Established by the DOAG | 27 February 1885 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 July 1890 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 October 1905 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 August 1914 | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Surrender | 25 November 1918 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 June 1919 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1913 | 1,001,475 km2 (386,672 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1913 | 7,700,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | German East African rupie | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||

The colony was organised when the German military was asked in the late 1880s to put down a revolt against the activities of the German East Africa Company. It ended with Imperial Germany's defeat in World War I. Ultimately, GEA was divided between Britain, Belgium and Portugal and was reorganised as a mandate of the League of Nations.

History

Like other colonial powers, the Germans expanded their empire in the Africa Great Lakes region, ostensibly to fight slavery and the slave trade. Unlike other imperial powers, however, they never formally abolished either, preferring instead to curtail the production of new "recruits" and regulate the existing slaving business.[3]

The colony began when Carl Peters, an adventurer who founded the Society for German Colonization, signed treaties with several native chieftains on the mainland opposite Zanzibar. On 3 March 1885, the German government announced that it had granted an imperial charter, which was signed by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck on 27 February 1885. The charter was granted to Peters' company and was intended to establish a protectorate in the African Great Lakes region. Peters then recruited specialists who began exploring south to the Rufiji River and north to Witu, near Lamu on the coast.[4][5][6]

The Sultan of Zanzibar protested, claiming that he was the ruler of both Zanzibar and the mainland. Chancellor Bismarck then sent five warships, which arrived on 7 August 1885 and trained their guns on the Sultan's palace. The British and Germans agreed to divide the mainland between themselves, and the Sultan had no option but to agree.[7]

German rule was established quickly over Bagamoyo, Dar es Salaam, and Kilwa. The caravans of Tom von Prince, Wilhelm Langheld, Emin Pasha, and Charles Stokes were sent to dominate "the Street of Caravans." The Abushiri Revolt of 1888 was put down with British help the following year. In 1890, London and Berlin concluded the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty, which returned Heligoland to Germany and decided the border between GEA and the East Africa Protectorate controlled by Britain, although the exact boundaries remained unsurveyed until 1910.[8][9]

Between 1891 and 1894, the Hehe people, led by Chief Mkwawa, resisted German expansion. They were defeated because rival tribes supported the Germans. After years of guerrilla warfare, Mkwawa himself was cornered and committed suicide in 1898.[10]

The Maji Maji Rebellion occurred in 1905[11] and was put down by Governor Gustav Adolf von Götzen, who ordered to create a famine to crush the resistance; it may have cost up to 300,000 deaths.[12][13] Scandal soon followed, however, with allegations of corruption and brutality. In 1907, Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow appointed Bernhard Dernburg to reform the colonial administration.[14][15]

German colonial administrators relied heavily on native chiefs to keep order and collect taxes. By 1 January 1914, aside from local police, the military garrisons of the Schutztruppen (protective troops) at Dar es Salaam, Moshi, Iringa, and Mahenge numbered 110 German officers (including 42 medical officers), 126 non-commissioned officers, and 2,472 Askari (native enlisted men).[16]:32

Economic development

Germans promoted commerce and economic growth. Over 100,000 acres (40,000 ha) were put under sisal cultivation, which was the largest cash crop.[17] Two million coffee trees were planted, rubber trees grew on 200,000 acres (81,000 ha), and there were large cotton plantations.[18]

To bring these agricultural products to market, beginning in 1888, the Usambara Railway was built from Tanga to Moshi. The Central Railroad covered 775 miles (1,247 km) and linked Dar es Salaam, Morogoro, Tabora, and Kigoma. The final link to the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika was completed in July 1914 and was cause for a huge and festive celebration in the capital with an agricultural fair and trade exhibition. Harbor facilities were built or improved with electrical cranes, with rail access and warehouses. Wharves were remodeled at Tanga, Bagamoyo, and Lindi. In 1912, Dar es Salaam and Tanga received 356 freighters and passenger steamers and over 1,000 coastal ships and local trading-vessels.[16]:30 Dar es Salaam became the showcase city of all of tropical Africa.[19]:22 By 1914, Dar es Salaam and the surrounding province had a population of 166,000, among them 1,000 Germans. In all of the GEA, there were 3,579 Germans.[16]:155

Gold mining in Tanzania in modern times dates back to the German colonial period, beginning with gold discoveries near Lake Victoria in 1894. The Kironda-Goldminen-Gesellschaft established one of the first gold mines in the colony, the Sekenke Gold Mine, which began operation in 1909 after the finding of gold there in 1907.[20]

Education

Germany developed an educational program for Africans that included elementary, secondary, and vocational schools. "Instructor qualifications, curricula, textbooks, teaching materials, all met standards unmatched anywhere in tropical Africa."[19]:21 In 1924, ten years after the beginning of the First World War and six years into British rule, the visiting American Phelps-Stokes Commission reported, "In regards to schools, the Germans have accomplished marvels. Some time must elapse before education attains the standard it had reached under the Germans."[19]:21

The Swahili word shule means school and has been borrowed from the German word Schule.[21]

Population on the eve of World War I

The most populous colony of the German Empire, there were more than 7.5 million locals, around 30% of whom were Muslim and the remainder belonging to various tribal beliefs or Christian converts, compared to around 10,000 Europeans, who resided mainly in coastal locations and official residences. In 1913, only 882 German farmers and planters lived in the colony. About 70,000 Africans worked on the plantations of GEA.[22]

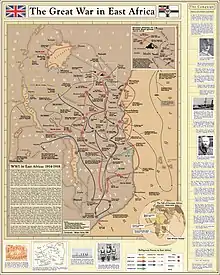

World War I

General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, who had served in German South West Africa and Kamerun, led the German military in GEA during World War I. His military consisted of 3,500 Europeans and 12,000 native Askaris and porters. Their war strategy was to harry the British/Imperial army of 40,000, which was at times commanded by the former Second Boer War commander Jan Smuts. One of Lettow-Vorbeck's greatest victories was at the Battle of Tanga (3–5 November 1914), where German forces defeated a British force more than eight times larger.[23]

Lettow-Vorbeck's guerrilla warfare compelled Britain to commit significant resources to a minor colonial theatre throughout the war and inflicted more than 10,000 casualties. Eventually, the weight of numbers, especially after forces coming from the Belgian Congo had attacked from the west (Battle of Tabora), and dwindling supplies forced Lettow-Vorbeck to abandon the colony. He withdrew south into Portuguese Mozambique, then into Northern Rhodesia where he agreed to a ceasefire three days after the end of the war after receiving news of the armistice between the warring nations.[24]

Lettow-Vorbeck was acclaimed after the war as one of Germany's heroes. His Schutztruppe was celebrated as the only colonial German force during World War I that was not defeated in open combat, although they often retreated when outnumbered. The Askari colonial troops that had fought in the East African campaign were later given pension payments by the Weimar Republic and West Germany.[25]

The SMS Königsberg, a German light cruiser, also fought off the coast of the African Great Lakes region. She was eventually scuttled in the Rufiji delta in July 1915 after running low on coal and spare parts and was subsequently blockaded and bombarded by the British. The surviving crew stripped out the remaining ship's guns and mounted them on gun carriages, before joining the land forces, adding considerably to their effectiveness.[26]

Another and smaller campaign was conducted on the shores of southern Lake Tanganyika over 1914–15. This involved a makeshift British and Belgian flotilla, and the Reichsheer garrison at Bismarckburg (modern-day Kasanga).

Break-up of the colony

The Supreme Council of the 1919 Paris Peace Conference awarded all of German East Africa (GEA) to Britain on 7 May 1919, over the strenuous objections of Belgium.[27]:240 The British colonial secretary, Alfred Milner, and Belgium's minister plenipotentiary to the conference, Pierre Orts, then negotiated the Anglo-Belgian agreement of 30 May 1919[28]:618–9 where Britain ceded the north-western GEA districts of Ruanda and Urundi to Belgium.[27]:246 The conference's Commission on Mandates ratified this agreement on 16 July 1919.[27]:246–7 The Supreme Council accepted the agreement on 7 August 1919.[28]:612–3

On 12 July 1919, the Commission on Mandates agreed that the small Kionga Triangle south of the Rovuma River would be given to Portugal,[27]:243 with it eventually becoming part of independent Mozambique. The commission reasoned that Germany had virtually forced Portugal to cede the triangle in 1894.[27]:243

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919, although the treaty did not take effect until 10 January 1920. On that date, the GEA was transferred officially to Britain, Belgium, and Portugal. Also on that date, "Tanganyika" became the name of the British territory.

German placenames

Most place names in German East Africa continued to bear German spellings of the local names, such as "Udjidji" for Ujiji and "Kilimandscharo" for Mount Kilimanjaro, as well as German translations of some local phrases, such as "Kleinaruscha" for Arusha-Chini and "Neu-Moschi" for the city now known as Moshi. (Kigoma was known for a time as "Rutschugi".)[29]

The few exceptions to the rule included:[30][31][32][33]

- Alt Langenburg (Ikombe)[31]

- Bergfrieden (Mibirizi)[31]

- Bismarckburg (Kasanga) on the south-eastern end of Lake Tanganyika[32]:v. I, p. 217[31]

- Emmaberg (Ilembule)[31]

- Fischerstadt (Rombo)[31]

- Friedberg (Nyakanazi)[31]

- Gottorp or Neu-Gottorp (Uvinza) near the northeastern end of Lake Tanganyika

- Hohenfriedeberg (Mlalo)[31]

- Hoffnungshöh (Kisarawe)[31]

- Kaiseraue (Kazimzumbwi)[31]

- Kirondathal (Kirondatal) gold mine

- Langenburg and Neu-Langenburg (Tukuyu) north of Lake Nyasa[31]

- Leudorf (Liganga)[31]

- Mariahilf (Igulwa)[31]

- Marienthal (Ushetu)[31]

- Neu-Bethel (Mnazi)[31]

- Neu-Bonn (Mikese)[31]

- Neu-Hornow (Shume) in the Pare Mountains in the northeast

- Neu-Langenburg (Lumbira)[31]

- Neu-Trier (Mbulu)[31]

- Peterswerft (Nansio)[31]

- Sachsenwald (Sekenke) gold mine

- St. Moritz (Galula)[31]

- Sphinxhafen (Liuli) on the eastern shore of Lake Nyasa

- Wiedhafen (Manda) on the eastern shore of Lake Nyasa

- Wilhelmstal or Wilhelmsdorf (Lushoto) on the Pangani River in the northeast

- Wißmannhafen, port of Bismarckburg (Kasanga) on the southeastern end of Lake Tanganyika

List of governors

The governors of German East Africa were as follows:[34]

- 1885–1888: Carl Peters (Reichskommissar)

- 1888–1891: Hermann Wissmann (Reichskommissar)

- 1891–1893: Julius von Soden

- 1893–1895: Friedrich von Schele

- 1895–1896: Hermann Wissmann

- 1896–1901: Eduard von Liebert

- 1901–1906: Gustav Adolf von Götzen

- 1906–1912: Albrecht von Rechenberg

- 1912–1918: Heinrich Schnee

Maps

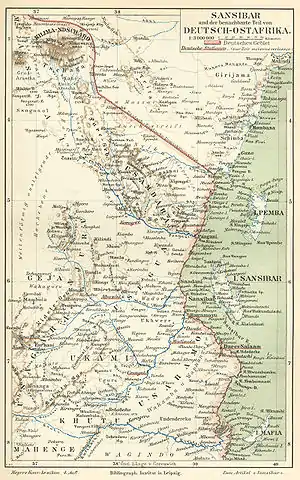

Historical map of the German East African coast, 1888

Historical map of the German East African coast, 1888 Historical map of German East Africa, 1892

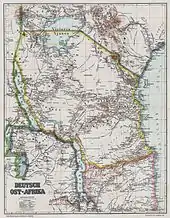

Historical map of German East Africa, 1892 Historical map of German East Africa, 1911

Historical map of German East Africa, 1911 Map of the East African Theater in World War I

Map of the East African Theater in World War I

Gallery

Sisal plantation, c. 1906/18

Sisal plantation, c. 1906/18 Sisal factory, c. 1906/18

Sisal factory, c. 1906/18 Askari company, c. 1914/18

Askari company, c. 1914/18 Classroom in a German East African school, c. March 1914

Classroom in a German East African school, c. March 1914 Usambara Railway, built in German East Africa

Usambara Railway, built in German East Africa German colonial volunteer mounted patrol, 1914

German colonial volunteer mounted patrol, 1914

Planned symbols for German East Africa

In 1914, a series of drafts were made for proposed Coat of Arms and Flags for the German Colonies. However, World War I broke out before the designs were finished and implemented and the symbols were never actually taken into use. Following the defeat in the war, Germany lost all its colonies and the prepared coat of arms and flags were therefore never used.

Proposed flag

Proposed flag Proposed coat of arms

Proposed coat of arms

References

- Roland Anthony Oliver (1976). Vincent Todd Harlow; Elizabeth Millicent Chilver; Alison Smith (eds.). History of East Africa, Volume 2. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198227137.

- Jon Bridgman; David E. Clarke (1965). "German Africa: A Selected Annotated Bibliography". Hoover Bibliographical Series. Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace, Stanford University. ISSN 0085-1582.

- Jan-Georg Deutsch (2006). Emancipation without Abolition in German East Africa, C. 1884–1914. James Currey. ISBN 978-0-852-55986-4.

- Arne Perras (2004). Carl Peters and German Imperialism 1856-1918: A Political Biography. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780199265107. OCLC 252667062.

- Hartmut Pogge von Strandmann (February 1969). "Domestic Origins of Germany's Colonial Expansion under Bismarck". Past & Present (42): 140–159. JSTOR 650184.

- Sara Friedrichsmeyer; Sara Lennox; Susanne Zantop (1998). The Imperialist Imagination: German Colonialism and Its Legacy. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472066827. OCLC 39679479.

- Dirk Göttsche (2013). Remembering Africa: The Rediscovery of Colonialism in Contemporary German Literature. Camden House. ISBN 9781571135469.

- James S. Olson (1991). Robert Shadle (ed.). Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 279–80. ISBN 9780313262579. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- David R. Gillard (October 1960). "Salisbury's African Policy and the Heligoland Offer of 1890". The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 75 (297): 631–653. JSTOR 558111.

- Alison Redmayne (1968). "Mkwawa and the Hehe Wars". The Journal of African History. 9 (3): 423. doi:10.1017/S0021853700008653. ISSN 1469-5138. JSTOR 180274.

- Iliffe, John (1967). "The Organization of the Maji Maji Rebellion". The Journal of African History. 8 (3): 495–512. doi:10.1017/s0021853700007982. JSTOR 179833.

- Iliffe, John (1979). A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge University Press. pp. 193–200. ISBN 9780521296113.

- Hull, Isabel V. (2003). "Military Culture and "Final Solutions"". In Gellately, Robert; Kiernan, Ben (eds.). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 151–62. ISBN 9780521527507.

- John S. Lowry (June 2006). "African Resistance and Center Party Recalcitrance in the Reichstag Colonial Debates of 1905/06". Central European History. 39 (2): 244–269. doi:10.1017/S0008938906000100. ISSN 1569-1616.

- Walter Nuhn (1998). Flammen über Deutschost: der Maji-Maji-Aufstand in Deutsch-Ostafrika 1905-1906, die erste gemeinsame Erhebung schwarzafrikanischer Völker gegen weisse Kolonialherrschaft: ein Beitrag zur deutschen Kolonialgeschichte. Bonn: Bernard & Graefe. ISBN 3763759697. OCLC 41980383.

- Werner Haupt (1984). Deutschlands Schutzgebiete in Übersee 1884–1918. Friedberg: Podzun-Pallas Verlag. ISBN 3-7909-0204-7.

- BRODE, H. (2016). BRITISH AND GERMAN EAST AFRICA: their economic commercial relations (classic reprint). [S.l.]: FORGOTTEN BOOKS. ISBN 978-1330527467. OCLC 980426986.

- "(HIS,P) Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas mit Jahrbuch (Atlas German Colonies, with Yearbook), edited by the German Colonial Society, 1905 - Deutsch-Ostafrika". www.zum.de. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- Charles Miller (1974). Battle for the Bundu, The First World War in East Africa. New York City: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc. ISBN 0-02-584930-1.

- Tanzania Mining History Archived 14 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine tanzaniagold.com, retrieved 24 July 2010

- "shule - Swahili-Old High German (ca. 750-1050) Dictionary". Glosbe. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- Längin, Bernd G. (2005). Die deutschen Kolonien. Mittler. p. 217. ISBN 3-8132-0854-0.

- Edwin P. Hoyt (1981). Guerilla: Colonel von Lettow-Vorbeck and Germany's East African Empire. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0025552104. OCLC 7732627.

- Brian M. DuToit (1998). The Boers in East Africa: ethnicity and identity. Westport, Connecticut: Bergin & Garvey. ISBN 0897896114. OCLC 646068752.

- Michael S. Neiberg (2001). Warfare in World History. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415229553. OCLC 52200068.

- Paul G. Halpern (1995). A naval history of World War I. UCL Press. ISBN 9781857284980. OCLC 60281302.

- Louis, William Roger (2006). Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez, and Decolonization. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511347-6.

- "Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, the Paris Peace Conference, 1919". United States Department of State. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Histoire sociale de l'Afrique de l'Est (XIXe-XXe siècle) : actes du colloque de Bujumbura, 17-24 octobre 1989. Université du Burundi. Département d'histoire. Paris: Karthala. 1991. ISBN 9782865373154. OCLC 25748614.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Koloniales Jahrbuch. Berlin : C. Heymann. 1888.

- Germany. Reichstag (1871). Stenographische Berichte über die Verhandlungen des Deutschen Reichstages. Princeton University. Berlin: Verlag der Buchdruckerei der "Norddeutschen Allgemeinen Zeitung".

- "Deutsch-Ostafrika". Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon (in German). 1920 – via Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt.

- Gustav Hermann Meinecke (1901). Deutscher kolonial-kalender und statistisches Handbuch...: Nach amtlichen Quellen neu Bearb (in German). New York Public Library. Deutscher kolonial -verlag.

- A. J. Dietz. "A postal history of the First World War in Africa and its aftermath - German colonies: II Kamerun" (PDF). African Studies Centre, Repository, Leiden University. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

Further reading

- British Foreign Office, Treatment of Natives in the German Colonies, H. M. Stationery Office, London, 1920.

- Bullock, A. L. C., Germany's Colonial Demands, Oxford University Press, 1939.

- East, John William. "The German Administration in East Africa: A Select Annotated Bibliography of the German Colonial Administration in Tanganyika, Rwanda and Burundi from 1884 to 1918." 294 leaves. Thesis submitted for the fellowship of the Library Association, London, November 1987."

- Farwell, Byron. The Great War in Africa, 1914–1918. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. 1989. ISBN 0-393-30564-3

- Hahn, Sievers. Afrika. 2nd Edition. Leipzig: Bibliographisches Institut. 1903.

- Schnee, Dr. Heinrich (Deputy Governor of German Samoa and last Governor of German East Africa), German Colonization, Past and Future – The Truth about the German Colonies, George Allen & Unwin, London, 1926.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to German East Africa. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for German East Africa. |

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). "German East Africa". Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). pp. 771–774.

- "German East Africa". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "German East Africa". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- The coins and bank notes of German East Africa

- Digitized archive of Deutsch-Ostafrikanische Zeitung (1899 - 1916)

.jpg.webp)