Laminitis

Laminitis is a disease that affects the feet of ungulates and is found mostly in horses and cattle. Clinical signs include foot tenderness progressing to inability to walk, increased digital pulses, and increased temperature in the hooves. Severe cases with outwardly visible clinical signs are known by the colloquial term founder, and progression of the disease will lead to perforation of the coffin bone through the sole of the hoof or being unable to stand up, requiring euthanasia.

Laminae

The bones of the hoof are suspended within the axial hooves of ungulates by layers of modified skin cells, known as laminae or lamellae, which act as shock absorbers during locomotion. In horses, there are about 550–600 pairs of primary epidermal laminae, each with 150–200 secondary laminae projection from their surface.[1] These interdigitate with equivalent structures on the surface of the coffin bone (PIII, P3, the third phalanx, pedal bone, or distal phalanx), known as dermal laminae.[2] The secondary laminae contain basal cells which attach via hemidesmosomes to the basement membrane. The basement membrane is then attached to the coffin bone via the connective tissue of the dermis.[1]

Pathophysiology

Laminitis literally means inflammation of the laminae, and while it remains controversial whether this is the primary mechanism of disease, evidence of inflammation occurs very early in some instances of the disease.[3] A severe inflammatory event is thought to damage the basal epithelial cells, resulting in dysfunction of the hemidesmosomes and subsequent reduction in adherence between the epithelial cells and the basement membrane.[4] Normal forces placed on the hoof are then strong enough to tear the remaining laminae, resulting in a failure of the interdigitation of the epidermal and dermal laminae between the hoof wall and the coffin bone. When severe enough, this results in displacement of the coffin bone within the hoof capsule.[4] Most cases of laminitis occur in both front feet, but laminitis may be seen in all four feet, both hind feet, or in cases of support limb laminitis, in a single foot.[4]

Mechanism

The mechanism remains unclear and is the subject of much research. Three conditions are thought to cause secondary laminitis:

- Sepsis/endotoxemia or generalized inflammation

- Endocrinopathy

- Trauma: concussion or excessive weight-bearing

- Inflammation

Inflammatory events that are associated with laminitis include sepsis, endotoxemia, retained placenta, carbohydrate overload (excessive grain or pasture), enterocolitis, pleuropneumonia, and contact with black walnut shavings.[5] In these cases, there is an increase in blood flow to the hoof, bringing in damaging substances and inflammatory cells into the hoof.

- Endocrinopathy

Endocrinopathy is usually the result of improper insulin regulation, and is most commonly seen with pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (also called equine Cushing's syndrome) and equine metabolic syndrome (EMS),[4] as well as obesity and glucocorticoid administration.[5] In cases of EMS, most episodes occur in the spring when the grass is lush.[4]

- Trauma

Mechanical laminitis starts when the hoof wall is pulled away from the bone or lost, as a result of external influences. Mechanical laminitis can occur when a horse habitually paws, is ridden or driven on hard surfaces ("road founder"), or in cases of excessive weight-bearing due to compensation for the opposing limb, a process called support limb laminitis. Support limb laminitis is most common in horses suffering from severe injury to one limb, such as fracture, resulting in a non-weight bearing state that forces them to take excessive load on the opposing limb. This causes decreased blood flow to the cells, decreasing oxygen and nutrient delivery, and thus altering their metabolism which results in laminitis.[1]

Theories of pathophysiology

- Matrix metalloproteinases

One of the newest theories for the molecular basis of laminitis involves matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Metalloproteinases are enzymes that can degrade collagen, growth factors, and cytokines to remodel the extracellular matrix of tissues. To prevent tissue damage, they are regulated by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). In cases of laminitis, an underlying cause is thought to cause an imbalance of MMPs and TIMPs, favoring MMPs, so that they may cleave substances within the extracellular matrix and therefore break down the basement membrane.[6] Since the basement membrane is the main link between the hoof wall and the connective tissue of P3, it is thought that its destruction results in their separation.[5] MMP-2 and MMP-9 are the primary enzymes thought to be linked to laminitis.[5]

- Theories for development

There are multiple theories as to how laminitis develops. These include:

- Enzymatic and inflammatory theories: The enzymatic theory postulates that increased blood flow to the foot brings in inflammatory cytokines or other substances to the hoof, where they increase production of MMPs, which subsequently break down the basement membrane. The inflammatory theory states that inflammatory mediators produce inflammation, but recognizes that MMP production occurs later. Therefore, this is possibly a 2-step process, beginning with inflammation and leading to MMP production and subsequent laminitis.[5]

- Vascular theory: Postulates that increases in capillary pressure, constriction of veins, and shunting of blood through anastomoses to bypass the capillaries, causes decreased blood and therefore decreased oxygen and nutrient delivery to lamellae. The end-result would be ischemia, leading to cellular death and breakdown between the lamellae. Subsequently, increased vascular permeability leads to edema within the hoof, compression of small vessels, and ischemia. Vasoactive amines may be partially to blame for changes in hoof blood flow.[5]

- Metabolic theory: Insulin affects multiple processes within the body, including inflammation, blood flow, and tissue remodeling. Change in insulin regulation may lead to laminitis.[5] Hyperinsulinemia has been shown to cause increased length of the secondary lamellae and epidermal cell proliferation.[1]

- Traumatic theory: Concussion is thought to directly damage lamellae, and increased weight-bearing is thought to decrease blood supply to the foot.[5]

Rotation, sinking, and founder

Normally, the front of the third phalanx is parallel to the hoof wall and its lower surface should be roughly parallel to the ground surface. A single severe laminitic episode or repeated, less severe episodes can, depending upon the degree of separation of dermal and epidermal laminae, lead to either rotation or sinking of the pedal bone, both of which result in anatomical changes in the position of the coffin bone with visible separation of the laminae, colloquially known as founder. Rotation and distal displacement may occur in the same horse.[4] Both forms of displacement may lead to the coffin bone penetrating the sole. Penetration of the sole is not inherently fatal; many horses have been returned to service by aggressive treatment by a veterinarian and farrier, but the treatment is time-consuming, difficult and expensive.

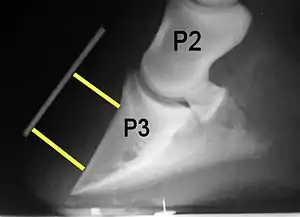

Rotation is the most common form of displacement, and, in this case, the tip of the coffin bone rotates downward.[4] The degree of rotation may be influenced by the severity of the initial attack and the time of initiation and aggressiveness of treatment. A combination of forces (e.g. the tension of the deep digital flexor tendon and the weight of the horse) result in the deep digital flexor tendon literally pulling the dorsal face of the coffin bone away from the inside of the hoof wall, which allows the coffin bone to rotate. Also, ligaments attaching the collateral cartilages to the digit, primarily in the palmar portion of the foot, possibly contribute to a difference in support from front to back. The body weight of the animal probably contributes to rotation of the coffin bone. Rotation results in an obvious misalignment between PII (the short pastern bone) and PIII (the coffin bone). If rotation of the third phalanx continues, its tip can eventually penetrate the sole of the foot.

Sinking is less common and much more severe. It results when a significant failure of the interdigitation between the sensitive and insensitive laminae around a significant portion of the hoof occurs. The destruction of the sensitive laminae results in the hoof wall becoming separated from the rest of the hoof, so that it drops within the hoof capsule. Sinking may be symmetrical, i.e., the entire bone moves distally, or asymmetric, where the lateral or medial aspect of the bone displaces distally.[4] Pus may leak out at the white line or at the coronary band. In extreme cases, this event allows the tip to eventually penetrate the sole of the foot. A severe "sinker" usually warrants the gravest prognosis and may, depending upon many factors, including the quality of aftercare, age of the horse, diet and nutrition, skill, and knowledge and ability of the attending veterinarian and farrier(s), lead to euthanasia of the patient.

Phases of laminitis

Treatment and prognosis depend on the phase of the disease, with horses treated in earlier stages often having a better prognosis.

- Developmental phase

The developmental phase is defined as the time between the initial exposure to the causative agent or incident, until the onset of clinical signs. It generally lasts 24–60 hours, and is the best time to treat a laminitis episode. Clinical laminitis may be prevented if cryotherapy (icing) is initiated during the developmental phase.[1]

- Acute phase

The acute phase is the first 72 hours following the initiation of clinical signs. Treatment response during this time determines if the horse will go into the subacute phase or chronic phase. Clinical signs at this time include bounding digital pulses, lameness, heat, and possibly response to hoof testing.[1]

- Subacute phase

The subacute phase occurs if there is minimal damage to the lamellae. Clinical signs seen in the acute phase resolve, and the horse becomes sound. The horse never shows radiographic changes, and there is no injury to the coffin bone.[1]

- Chronic phase

The chronic phase occurs if damage to the lamellae is not controlled early in the process, so that the coffin bone displaces. Changes that may occur include separation of the dermal and epidermal lamellae, lengthening of the dermal lamellae, and compression of the coronary and solar dermis. If laminitis is allowed to continue, long-term changes such as remodeling of the apex and distal border of the coffin bone (so that a "lip" develops) and osteolysis of the coffin bone can occur.[1]

The chronic phase may be compensated or uncompensated. Compensated cases will have altered hoof structure, including founder rings, wide white lines, and decreased concavity to the sole. Horses will be relatively sound. On radiographs, remodeling of the coffin bone and in cases of rotational displacement, the distal hoof wall will be thicker than that proximally. Venograms will have relatively normal contrast distribution, including to the apex and distal border of the coffin bone, and the coronary band, but "feathering" may be present at the lamellar "scar."[1]

Uncompensated cases will develop a lamellar wedge (pathologic horn), leading to a poor bridge between P3 and the hoof capsule. This will lead to irregular horn growth and chronic lameness, and horses will suffer from laminitis "flares." Inappropriate hoof growth will occur: the dorsal horn will have a tendency to grow outward rather than down, the heels will grow faster than the toe, and the white line will widen, leading to a potential space for packing of debris. The solar dermis is often compressed enough to inhibit growth, leading to a soft, thin sole (<10 mm) that may develop seromas. In severe cases where collapse of the suspensory apparatus of P3 has occurred, the solar dermis or the tip of P3 may penetrate the sole. The horse will also be prone to recurrent abscessation within the hoof capsule. Venogram will show "feathering" into the vascular bed beneath the lamellae, and there will be decreased or absent contrast material in the area distal to the apex of the coffin bone.[1]

Causes

Laminitis has multiple causes, some of which commonly occur together. These causes can be grouped into broad categories.

Endotoxins

- Carbohydrate overload: One of the more common causes, current theory states that if a horse is given grain in excess or eats grass under stress and has accumulated excess nonstructural carbohydrates (sugars, starch, or fructan), it may be unable to digest all of the carbohydrate in the foregut. The excess then moves on to the hindgut and ferments in the cecum. The presence of this fermenting carbohydrate in the cecum causes proliferation of lactic acid bacteria and an increase in acidity. This process kills beneficial bacteria, which ferment fiber. The endotoxins and exotoxins may then be absorbed into the bloodstream, due to increased gut permeability, caused by irritation of the gut lining by increased acidity. The result is body-wide inflammation, but particularly in the laminae of the feet, where swelling tissues have no place to expand without injury to other structures. This results in laminitis.

- Nitrogen compound overload: Herbivores are equipped to deal with a normal level of potentially toxic nonprotein nitrogen compounds in their forage. If, for any reason, rapid increases in levels of these compounds occur, for instance in lush spring growth on fertilized lowland pasture, the natural metabolic processes can become overloaded, resulting in liver disturbance and toxic imbalance. For this reason, many avoid using synthetic nitrogen fertilizer on horse pasture. If clover (or any legume) is allowed to dominate the pasture, this may also allow excess nitrogen to accumulate in forage, under stressful conditions such as frost or drought. Many weeds eaten by horses are nitrate accumulators. Direct ingestion of nitrate fertilizer material can also trigger laminitis, by a similar mechanism.

- Colic: Laminitis can sometimes develop after a serious case of colic, due to the release of endotoxins into the blood stream.

- Lush pastures: When releasing horses back into a pasture after being kept inside (typically during the transition from winter stabling to spring outdoor keeping), the excess fructan of fresh spring grass can lead to a bout of laminitis. Ponies and other easy keepers are much more susceptible to this form of laminitis than are larger horses.

- Frosted grass: Freezing temperatures in the fall also coincide with outbreaks of laminitis in horses at pasture. Lower temperatures cause growth to cease, so sugar in pasture grasses cannot be used by the plant as fast as it is produced, thus they accumulate in the forage. Cool-season grasses form fructan, and warm season grasses form starch.[7] Sugars cause increases in insulin levels, which are known to trigger laminitis. Fructan is theorized to cause laminitis by causing an imbalance of the normal bowel flora leading to endotoxin production. These endotoxins may exacerbate insulin resistance, or the damage to the lining of the gut may release other as yet unidentified trigger factors into the blood stream. For horses prone to laminitis, restrict or avoid grazing when night temperatures are below 40 °F (5 °C) followed by sunny days. When growth resumes during warmer weather, sugar will be used to form protein and fiber and will not accumulate.

- Untreated infections: Systemic infections, particularly those caused by bacteria, can cause release of endotoxins into the blood stream. A retained placenta in a mare (see below) is a notorious cause of laminitis and founder.

- Insulin resistance: Laminitis can also be caused by insulin resistance in the horse. Insulin-resistant horses tend to become obese very easily and, even when starved down, may have abnormal fat deposits in the neck, shoulders, loin, above the eyes, and around the tail head, even when the rest of the body appears to be in normal condition. The mechanism by which laminitis associated with insulin resistance occurs is not understood, but may be triggered by sugar and starch in the diet of susceptible individuals. Ponies and breeds that evolved in relatively harsh environments, with only sparse grass, tend to be more insulin-resistant, possibly as a survival mechanism. Insulin-resistant animals may become laminitic from only very small amounts of grain or "high sugar" grass. Slow adaptation to pasture is not effective, as it is with laminitis caused by microbial population upsets. Insulin-resistant horses with laminitis must be removed from all green grass and be fed only hay tested for nonstructural carbohydrates (sugar, starch and fructan) and found to be below 11% on a dry-matter basis.

Vasoactive amines

The inflammatory molecule histamine has also been hypothesized as a causative agent of laminitis.[8][9] However, contradictory evidence indicates the role of histamine in laminitis has not been conclusively established.[10]

Mechanical separation

Commonly known as road founder, mechanical separation occurs when horses with long toes are worked extensively on hard ground. The long toes and hard ground together contribute to delayed breakover, hence mechanical separation of the laminae at the toe. Historically, this was seen in carriage horses bred for heavy bodies and long, slim legs with relatively small hooves; their hooves were trimmed for long toes (to make them lift their feet higher, enhancing their stylish "action"), and they were worked at speed on hard roads. Road founder is also seen in overweight animals, particularly when hooves are allowed to grow long; classic examples are ponies on pasture board in spring, and pregnant mares.[11]

Poor blood circulation

Normal blood circulation in the lower limbs of a horse depends in part on the horse moving about. Lack of sufficient movement, alone or in combination with other factors, can cause stagnant anoxia, which in turn can cause laminitis.[11]

A horse favoring an injured leg will both severely limit its movement and place greater weight on the other legs. This sometimes leads to static laminitis, particularly if the animal is confined in a stall.[11] A notable example is the 2006 Kentucky Derby winner Barbaro.[12]

Transport laminitis sometimes occurs in horses confined in a trailer or other transportation for long periods of time. Historically, the most extreme instances were of horses shipped overseas on sailing ships. However, the continual shifting of weight required to balance in a moving vehicle may enhance blood circulation, so some horsemen recommend trailering as an initial step in rehabilitation of a horse after long confinement.

Laminitis has been observed following an equine standing in extreme conditions of cold, especially in deep snow. Laminitis has also followed prolonged heating such as may be experienced from prolonged contact with extremely hot soil or from incorrectly applied hot-shoeing.

Complex causes

- Pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction, or Cushing's disease, is common in older horses and ponies and causes an increased predisposition to laminitis.

- Equine metabolic syndrome is a subject of much new research and is increasingly believed to have a major role in laminitis. It involves many factors such as cortisol metabolism and insulin resistance. It has some similarities to type II diabetes in humans. In this syndrome, peripheral fat cells synthesise adipokines which are analogous to cortisol, resulting in Cushings-like symptoms.

- A retained placenta, if not passed completely after the birth of a foal, can cause mares to founder, whether through toxicity, bacterial fever, or both.

- Anecdotal reports of laminitis following the administration of drugs have been made, especially in the case of corticosteroids. The reaction may be an expression of idiosyncrasy in a particular patient, as many horses receive high dose glucocorticoid into their joints without showing any evidence of clinical laminitis.[13] [14]

- Even horses not considered to be susceptible to laminitis can become laminitic when exposed to certain agrichemicals. The most commonly experienced examples are certain herbicides and synthetic nitrate fertilizer.

Risk factors

Whilst diet has long been known to be linked to laminitis, there is emerging evidence that breed and body condition also play a role.[15] Levels of hormones, particularly adiponectin, and serum insulin are also implicated, opening up new possibilities for developing early prognostic tests and risk assessments.[16]

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis is essential to effective treatment. However, early outward signs may be fairly nonspecific. Careful physical examination typically is diagnostic, but radiographs are also very useful.

Clinical signs

- Increased temperature of the wall, sole and/or coronary band of the foot[4]

- A pounding pulse in the digital palmar artery[4]

- Anxiety and visible trembling

- Increased vital signs and body temperature

- Sweating

- Flared nostrils

- Walking very tenderly, as if walking on egg shells

- Repeated "easing" of affected feet, i.e. constant shifting of weight

- Lameness with a positive response to hoof testers at the toe[4]

- The horse stands in a "founder stance" in attempt to decrease the load on the affected feet. If it has laminitis in the front hooves, it will bring its hind legs underneath its body and put its fore legs out in front.[4] In cases of sinking, the horse stands with all four feet close together, like a circus elephant.

- Tendency to lie down whenever possible, and recumbency in extreme cases[4]

- Change in the outward appearance of the hoof in cases of chronic laminitis: dished (concave) dorsal hoof wall, "founder rings" (growth rings that are wider at the heel than the toe), a sole that is either flat or convex just dorsal to the apex of the frog which indicates P3 has displaced or penetrated, widening of the white line at the toe with or without bruising, "clubbing" of the foot.[1][4]

- Change in the appearance of the coronary band: hair that does not lie in a normal position (not against the hoof wall), indentation or rim just above the hoof capsule allowing palpation behind the coronary band.[1]

- In cases of sinking, it may be possible to palpate a groove between the coronary band and the skin of the pastern.[4]

Lameness evaluation

- Hoof testing

Laminitic horses are generally sore to pressure from hoof testers applied over the toe area. However, there is risk of a false negative if the horse naturally has a thick sole, or if the hoof capsule is about to slough.[1]

- Obel grading system

The severity of lameness is qualified using the Obel grading system:[17]

- Obel grade 1: Horse shifts weight between affected feet or continuously lifts feet up. It is sound at the walk but displays a shortened stride at the trot.

- Obel grade 2: Horse displays a stilted, stiff gait, although is willing to walk. It is possible to easily lift a front foot and have the horse take all of its weight on the contralateral limb.

- Obel grade 3: Horse displays a stilted, stiff gait, but is reluctant to walk and is difficult when asked to lift a front foot.

- Obel grade 4: Horse is very reluctant to move, or is recumbent.

- Nerve blocks

Horses suffering from the disease usually require an abaxial sesamoid block to relieve them of pain, since the majority of pain comes from the hoof wall. However, chronic cases may respond to a palmar digital block since they usually have primarily sole pain.[4] Severe cases may not respond fully to nerve blocks.[1]

Radiographs

Radiographs are an important part of evaluating the laminitic horse. They not only allow the practitioner to determine the severity of the episode, which does not always correlate with degree of pain,[1] but also to gauge improvement and response to treatment. Several measurements are made to predict severity. Additionally, radiographs also allow the visualization and evaluation of the hoof capsule, and can help detect the presence of a lamellar wedge or seromas.[1] The lateral view provides the majority of the information regarding degree of rotation, sole depth, dorsal hoof wall thickness, and vertical deviation.[1][18] A 65-degree dorsopalmar view is useful in the case of chronic laminitis to evaluate the rim of the coffin bone for pathology.[1]

- Radiographic measurements

Several radiographic measurements, made on the lateral view, allow for objective evaluation of the episode.

- Coronary extensor distance (CE): the vertical distance from the level of the proximal coronary band to the extensor process of P3. It is often used to compare progression of the disease over time, rather than as a stand-alone value. A rapidly increasing CE value can indicate distal displacement (sinking) of the coffin bone, while a more gradual increase in CE can occur with foot collapse. Normal values range from 0–30 mm, with most horses >12–15 mm.[1]

- Sole depth (SD): the distance from the tip of P3 to the ground.

- Digital breakover (DB): distance from the tip of P3 to the breakover of the hoof (dorsal toe).[1]

- Palmar angle (PA): the angle between a line perpendicular to the ground, and a line at the angle of the palmar surface of P3.

- Horn:lamellar distance (HL): the measurement from the most superficial aspect of the dorsal hoof wall to the face of P3. 2 distances are compared: a proximal measurement made just distal to the extensor process of P3, and a distal measurement made toward the tip of P3. These two values should be similar. In cases of rotation, the distal measurement will be higher than the proximal. In cases of distal displacement, both values will increase, but may remain equal. Therefore, it is ideal to have baseline radiographs for horses, especially for those at high-risk for laminitis, to compare to should laminitis ever be suspected. Normal HL values vary by breed and age:[1]

- Weanlings will have a greater proximal HL compared to distal HL

- Yearlings will have approximately equal proximal and distal HL

- Thoroughbreds are usually 17mm proximally, and 19mm distally

- Standardbreds have been shown to have a similar proximal and distal HL, around 16 mm at 2 years old, and 20 mm at 4 years old

- Warmbloods have similar proximal and distal values, up to 20 mm each

- HL tends to increase with age, up to 17 mm in most light breeds, or higher, especially in very old animals

- Venograms

Venograms can help determine the prognosis for the animal, particularly in horses where the degree of pain does not match the radiographic changes. In venography, a contrast agent, visible on radiographs, is injected into the palmar digital vein to delineate the vasculature of the foot.[1] The venogram can assess the severity and location of tissue compromise and monitor effectiveness of the current therapy.[18] Compression of veins within the hoof will be seen as sections that do not contain contrast material. Poor or improper blood flow to different regions of the hoof help determine the severity of the laminitic episode. Venography is especially useful for early detection of support limb laminitis, as changes will be seen on venograph (and MRI) within 1–2 weeks, whereas clinical signs and radiographic changes do not manifest until 4–6 weeks.[1]

Horses undergoing venography have plain radiographs taken beforehand to allow for comparison. The feet are blocked to allow the sedated horse to stand comfortably during the procedure. Prior to injection, a tourniquet is placed around the fetlock to help keep the contrast material within the foot during radiography. Diffusion of contrast may make some areas appear hypoperfused, falsely increasing the apparent severity of the laminitic episode. After injection of the contrast material, films are taken within 45 seconds to avoid artifact caused by diffusion. Evaluation of blood supply to several areas of the foot allows the practitioner to distinguish mild, moderate, and severe compromise of the hoof, chronic laminitis, and sinking.[1]

Other diagnostics

Other imaging tools have been used to show mechanical deviations in laminitis cases include computed tomography, as well as MRI, which also provides some physiologic information. Nuclear scintigraphy may also be useful in certain situations. Ultrasonography has been explored as a way to quantify changes in bloodflow to the foot.[19]

Prognosis

The sooner the diagnosis is made, the faster the treatment and the recovery process can begin. Rapid diagnosis of laminitis is often difficult, since the general problem often starts somewhere else in the horse's body. With modern therapies, most laminitics will be able to bear a rider or completely recover, if treated quickly, and if the laminitis was not severe or complicated (e.g. by equine metabolic syndrome or Cushing's disease). Even in these cases, a clinical cure can often be achieved. Endotoxic laminitis (e.g. after foaling) tends to be more difficult to treat. Successful treatment requires a competent farrier and veterinarian, and success is not guaranteed. A horse can live with laminitis for many years, and although a single episode of laminitis predisposes to further episodes, with good management and prompt treatment it is by no means the catastrophe sometimes supposed: most horses suffering an acute episode without pedal bone displacement make a complete functional recovery. Some countermeasures can be adopted for pasture based animals.[20][21] Discovery of laminitis, either active or relatively stabilized, on an equine prepurchase exam typically downgrades the horse's value, as the possibility of recurrence is a significant risk factor for the future performance of the horse.

Several radiographic abnormalities can be judged to correlate with a worsened prognosis:

- Increased degree of rotation of P3 relative to the dorsal hoof wall (rotation greater than 11.5 degrees has a poorer prognosis)[4]

- Increased founder distance, the vertical distance from the coronary band (seen with a radio-opaque marker) to the dorsoproximal aspect of P3 (distance greater than 15.2mm has a poorer prognosis)[4]

- Decreased sole depth[4]

- Sole penetration by P3

Treatment

In laminitis cases, a clear distinction must be made between the acute onset of a laminitis attack and a chronic situation. A chronic situation can be either stable or unstable. The difference between acute, chronic, stable, and unstable is of vital importance when choosing a treatment protocol. There is no cure for a laminitic episode and many go undetected. Initial treatment with cryotherapy and anti-inflammatory drugs may prevent mechanical breakdown if instituted immediately, but many cases are only detected after the initial microscopic damage has been done. In cases of sepsis or endotoxemia, the underlying cause should be addressed concurrently with laminitis treatment.[4] There are various methods for treating laminitis, and opinions vary on which are most useful. Additionally, the each horse and affected hoof should be evaluated individually to determine the best treatment plan, which may change with time.[1] Ideally, affected hooves are re-evaluated on a regular basis once treatment commences to track progress.[1]

Management

Initial management usually includes stall rest to minimize movement, and deeply bedding the stall with shavings, straw, or sand. Exercise is slowly increased once the horse has improved, ideally in an area with good (soft) footing, beginning with hand-walking, then turn-out, and finally riding under saddle.[1] This process may take months to complete.[1]

Cryotherapy

Cooling of the hoof in the developmental stages of laminitis has been shown to have a protective effect when horses are experimentally exposed to carbohydrate overload. Feet placed in ice slurries were less likely to experience laminitis than "uniced" feet.[22] Cryotherapy reduces inflammatory events in the lamellae. Ideally, limbs should be placed in an ice bath up to the level of the knee or hock. Hooves need to be maintained at a temperature less than 10 degrees Celsius at the hoof wall, for 24–72 hours.[1]

In the case of a full-blown case of laminitis, use of a cold water spa proved effective in the treatment of Bal a Bali. For the first three days, Bal a Bali was kept in the spa for eight hours at a time. Once his condition stabilized, he continued to be put in the spa twice a day over the next few months.[23]

Drug therapies

- Anti-inflammatories and analgesics

Anti-inflammatories are always used when treating acute case of laminitis, and include Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDS), DMSO, pentoxpfylline, and cryotherapy.[4] For analgesia, NSAIDs are often the first line of defense. Phenylbutazone is commonly used for its strong effect and relatively low cost. Flunixin (Banamine), ketofen, and others are also used. Nonspecific NSAIDs such as suxibuzone, or COX-2-specific drugs, such as firocoxib and diclofenac, may be somewhat safer than phenylbutazone in preventing NSAID toxicity such as right dorsal colitis, gastric ulcers, and kidney damage.[24][25][26] However, firocoxib provides less pain relief than phenylbutazone or flunixin.[1] Care must be taken that pain is not totally eliminated, since this will encourage the horse to stand and move around, which increases mechanical separation of the laminae.[1]

Pentafusion, or the administration of ketamine, lidocaine, morphine, detomidine, and acepromazine at a constant rate of infusion, may be of particular benefit to horses suffering from laminitis.[4] Epidurals may also be used in hind-limb laminitis.[4]

- Vasodilators

Vasodilators are often used with the goal of improving laminar blood flow. However, during the developmental phases of laminitis, vasodilation is contraindicated, either through hot water or vasodilatory drugs.[27] Systemic acepromazine as a vasodilator with the fringe benefit of mild sedation which reduces the horse/pony's movements and thus reduces concussion on the hooves, may be beneficial after lamellar damage has occurred, although no effects on laminar blood flow with this medication have been shown.[28] Nitroglycerine has also been applied topically in an attempt to increase blood flow, but this treatment does not appear to be an effective way to increase blood flow in the equine digit.[29]

Trimming and shoeing

Besides pain management and control of any predisposing factors, mechanical stabilization is a primary treatment goal once the initial inflammatory and metabolic issues have resolved. No approach has been shown to be effective in all situations, and debate is ongoing the merits and faults of the numerous techniques. Once the distal phalanx rotates, it is essential to derotate and re-establish its proper spatial orientation within the hoof capsule, to ensure the best long-term prospects for the horse. With correct trimming and, as necessary, the application of orthotics, one can effect this reorientation. However, this is not always completely effective.

- Trimming

Successful treatment for any type of founder must necessarily involve stabilization of the bony column by some means. Correct trimming can help improve stabilization. This usually includes bringing the "break over" back to decrease the fulcrum-effect that stresses the laminae. Trimming the heels helps to ensure frog pressure and increases surface area for weight-bearing on the back half of the hoof.[1] While horses may stabilize if left barefooted, some veterinarians believe the most successful methods of treating founder involve positive stabilisation of the distal phalanx, by mechanical means, e.g., shoes, pads, polymeric support, etc. Pour-in pads or putty is sometimes placed on the sole to increase surface area for weight-bearing, so that the sole in the area of the quarters, and the bars, will take some of the weight.[1]

- Altering the palmar angle

The deep digital flexor tendon places a constant pull on the back of the coffin bone. This is sometimes counteracted by decreasing the palmar angle of the hoof by raising the heels, often with the use of special shoes which have a wedge in the heel of approximately 20 degrees. Shoes are usually glued or cast onto the foot so painful nailing does not have to take place. The position of P3 within the hoof is monitored with radiographs. Once the horse has improved, the wedge of the shoe must be slowly reduced back to normal.[1]

- Use of orthotics

The application of external orthotic devices to the foot in a horse with undisplaced laminitis and once displacement has occurred is widespread. Most approaches attempt to shift weight away from the laminae and onto secondary weight-bearing structures, while sparing the sole.

- Corrective hoof trimming

Corrective hoof trimming will restore proper hoof form and function. Corrective trimming will allow the hooves to be healthy again.

- Realigning trimming

Realigning trimming trims back the toe so that it is in line with the coffin bone. Realigning trimming pushes the coffin bone back into the correct position. The process of a new hoof capsule totally growing out to replace the old one takes up to a year.

Aggressive therapies

- Dorsal hoof wall resection

A dorsal hoof wall resection may help in certain conditions after consultation with an experienced veterinarian and farrier team. If decreased bloodflow distal to the coronary plexus is seen on a venogram, or when a laminar wedge forms between P3 and the hoof wall, preventing the proper reattachment (interdigitation) of the laminae, this procedure may be beneficial. When the coffin bone is pulled away from the hoof wall, the remaining laminae will tear. This may lead to abscesses within the hoof capsule that can be severe and very painful, as well as a mass of disorganized tissue called a laminar (or lamellar) wedge.[30]

- Coronary grooving

Coronary grooving involves removing a groove of hoof wall just distal to the coronary band. It is thought to encourage dorsal hoof wall growth and improve alignment of the wall.[4]

- Deep digital flexor tenotomy

Because the rotation of P3 is exacerbated by continued pull on the deep digital flexor tendon, one approach to therapy has been to cut this tendon, either in the cannon region (mid-metacarpus)[4] or in the pastern region. Over a time period of 6 weeks, tenotomy is thought to allow P3 to realign with the ground surface.[4] Critics claim that this technique is unsuccessful and invasive, with advocates making counter-arguments that it is often used in cases which are too far advanced for treatment to help.[31] Tenotomy does risk subluxation of the distal interphalangeal joint (coffin joint),[4] which may be avoided with the use of heel extensions on the shoe.[1] Horses may return to work after the surgery.[1] This treatment is often recommended for severe cases of laminitis, and requires proper trimming and shoeing to be successful.[1]

- Botulinum toxin infusion

As an alternative to the deep digital flexor tenotomy, Clostridium botulinum type A toxin has been infused into the body of the deep digital flexor muscle. This theoretically allows for the same derotation as a tenotomy, but without the potential for scarring or contracture associated with that procedure. A recent study used this technique in seven laminitic horses. Significant improvement was seen in six of the horses, with moderate improvement in the seventh.[32]

Complications

Complications to laminitis include recurrent hoof abscesses, which are sometimes secondary to pedal osteitis,[1] seromas, and fractures to the solar margin of the coffin bone.[4]

Informal use of the word "founder"

Informally, particularly in the United States, "founder" has come to mean any chronic changes in the structure of the foot that can be linked to laminitis. In some texts, the term is even used synonymously with laminitis, though such usage is technically incorrect. Put simply, not all horses that experience laminitis will founder, but all horses that founder will first experience laminitis.

References

- Orsini J, Divers T (2014). Equine Emergencies (4th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. pp. 697–712. ISBN 978-1-4557-0892-5.

- Pollitt CC (1995). Color Atlas of the Horse's Foot. Mosby. ISBN 978-0-7234-1765-1.

- Loftus JP, Black SJ, Pettigrew A, Abrahamsen EJ, Belknap JK (November 2007). "Early laminar events involving endothelial activation in horses with black walnut- induced laminitis". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 68 (11): 1205–11. doi:10.2460/ajvr.68.11.1205. PMID 17975975.

- Baxter G (2011). Manual of Equine Lameness (1st ed.). Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 257–262. ISBN 978-0-8138-1546-6.

- Huntington P, Pollitt C, McGowan C (September 2009). "Recent research into laminitis" (PDF). Advances in Equine Nutrition. IV: 293. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- de Laat MA, Kyaw-Tanner MT, Nourian AR, McGowan CM, Sillence MN, Pollitt CC (April 2011). "The developmental and acute phases of insulin-induced laminitis involve minimal metalloproteinase activity" (PDF). Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 140 (3–4): 275–81. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.01.013. PMID 21333362.

- Watts KA (March 2004). "Forage and Pasture Management for Laminitic Horses" (PDF). Clinical Techniques in Equine Practice. 3 (1): 88–95. doi:10.1053/j.ctep.2004.07.009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-12-31. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- Nilsson SA (1963). "Clinical, morphological and experimental studies of laminitis in cattle". Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 4 (Suppl. 1): 188–222. OCLC 13816616.

- Takahashi K, Young BA (June 1981). "Effects of grain overfeeding and histamine injection on physiological responses related to acute bovine laminitis". Nihon Juigaku Zasshi. The Japanese Journal of Veterinary Science. 43 (3): 375–85. doi:10.1292/jvms1939.43.375. PMID 7321364.

- Thoefner MB, Pollitt CC, Van Eps AW, Milinovich GJ, Trott DJ, Wattle O, Andersen PH (September 2004). "Acute bovine laminitis: a new induction model using alimentary oligofructose overload". Journal of Dairy Science. 87 (9): 2932–40. doi:10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(04)73424-4. PMID 15375054.

- Rooney J. "Nonclassical laminitis". Archived from the original on 2008-01-24.

- "Transcript of Press Conference on the condition of Barbaro" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. 13 July 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2007.

- McCluskey, M. J.; Kavenagh, P. B. (2010). "Clinical use of triamcinolone acetonide in the horse (205 cases) and the incidence of glucocorticoid‐induced laminitis associated with its use". Equine Veterinary Education. 16 (2): 86–89. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3292.2004.tb00272.x.

- "No Evidence That Therapeutic Systemic Corticosteroid Administration is Associated With Laminitis in Adult Horses Without Underlying Endocrine or Severe Systemic Disease".

- Luthersson N, Mannfalk M, Parkin TD, Harris P (2017). "Laminitis: Risk Factors and Outcome in a Group of Danish Horses" (PDF). Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 53: 68–73. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2016.03.006.

- Menzies-Gow NJ, Harris PA, Elliott J (May 2017). "Prospective cohort study evaluating risk factors for the development of pasture-associated laminitis in the United Kingdom" (PDF). Equine Veterinary Journal. 49 (3): 300–306. doi:10.1111/evj.12606. PMID 27363591.

- Anderson M. "The Obel Grading System for Describing Laminitis". www.thehorse.com. The Horse. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- Ramey P, Bowker RM (2011). Care and Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot. Hoof Rehabilitation Publisher. pp. 234–253. ISBN 978-0-615-52453-5.

- Wongaumnuaykul S, Siedler C, Schobesberger H, Stanek C (2006). "Doppler sonographic evaluation of the digital blood flow in horses with laminitis or septic pododermatitis". Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound. 47 (2): 199–205. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8261.2006.00128.x. PMID 16553154.

- Harris P, Bailey SR, Elliott J, Longland A (July 2006). "Countermeasures for pasture-associated laminitis in ponies and horses". The Journal of Nutrition. 136 (7 Suppl): 2114S–2121S. doi:10.1093/jn/136.7.2114S. PMID 16772514.

- Colahan P, Merritt A, Moore J, Mayhew I (December 1998). Equine Medicine and Surgery (Fifth ed.). Mosby. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-8151-1743-8.

- Pollitt C (November 2003). "Equine Laminitis" (PDF). Proceedings of the AAEP. 49. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-03-08. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- Shulman L. "Making of a Miracle" (PDF). vet.osu.edu (reprint from The Blood-Horse). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- MacAllister CG, Morgan SJ, Borne AT, Pollet RA (January 1993). "Comparison of adverse effects of phenylbutazone, flunixin meglumine, and ketoprofen in horses". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 202 (1): 71–7. PMID 8420909.

- Sabaté D, Homedes J, Mayós I, Calonge R, et al. (January 2005). Suxibuzone as a Therapeutical Alternative to Phenylbutazone in the Treatment of Lameness in Horses (PDF). 11th SIVE Congress. Pisa. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2005-05-29. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- Doucet MY, Bertone AL, Hendrickson D, Hughes F, Macallister C, McClure S, et al. (January 2008). "Comparison of efficacy and safety of paste formulations of firocoxib and phenylbutazone in horses with naturally occurring osteoarthritis". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 232 (1): 91–7. doi:10.2460/javma.232.1.91. PMID 18167116.

- Pollitt CC (2003). "Medical Therapy of Laminitis". In Ross MW, Dyson SJ (eds.). Diagnosis and Management of Lameness in the Horse. St. Louis, MO: Saunders. p. 330. ISBN 0-7216-8342-8.

- Adair HS, Schmidhammer JL, Goble DO, et al. (1997). "Effects of acepromazine maleate, isoxsuprine hydrochloride and prazosin hydrochloride on laminar blood flow in healthy horses". Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 17: 599–603. doi:10.1016/S0737-0806(97)80186-4.

- Belknap JK, Black SJ (2005). "Review of the Pathophysiology of the Developmental Stages of Equine Laminitis". Proceedings American Association of Equine Practitioners. 51.

- Eustace RA (1996). Explaining Laminitis and its Prevention. Cherokee, Ala.: Life Data Labs. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-9518974-0-9.

- Eastman TG, Honnas CM, Hague BA, Moyer W, von der Rosen HD (February 1999). "Deep digital flexor tenotomy as a treatment for chronic laminitis in horses: 35 cases (1988-1997)" (PDF). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 214 (4): 517–9. PMID 10029854.

- Carter DW, Renfroe JB (July 2009). "A novel approach to the treatment and prevention of laminitis: botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of laminitis". Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 29 (7): 595–600. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2009.05.008.

Further reading

- Baxter GM, ed. (March 2011). Adams and Stashak's Lameness in Horses (6th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-813-81549-7.

- Rooney JR (1998). The Lame Horse. Russell Meerdink Company. ISBN 978-0-929346-55-7.

- Wagoner DM, ed. (1977). The Illustrated Veterinary Encyclopedia for Horsemen. Equine Research Inc. ISBN 978-0-935842-03-6.

- Adams HR, Chalkley LW, Buchanan TM, Wagoner DM, eds. (1977). Veterinary Medications and Treatments for Horsemen. Equine Research Inc. ISBN 978-0-935842-01-2.

- Giffin JM, Gore T (July 2008). Horse Owner's Veterinary Handbook (Third ed.). Howell Book House. ISBN 978-0-470-12679-0.

- Jackson J (March 2001). Founder: Prevention & Cure the Natural Way. Star Ridge Company. ISBN 978-0-9658007-3-0.

- Strasser H (2003). Who's Afraid of Founder. Laminitis Demystified: Causes, Prevention and Holistic Rehabilitation. Sabine Kells. ISBN 978-0-9685988-4-9.

- Curtis S (June 2006). Corrective Farriery, a textbook of remedial horseshoeing. R & W Publications (Newmarket) Ltd. ISBN 978-1-899772-13-1.

- Butler D (2004). The Principles of Horseshoeing II and The Principles of Horseshoeing III. ISBN 978-0-916992-26-2.

- Riegel RJ, Hakola SE (1999). Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Equine Anatomy and Common Disorders of the Horse. One. Equistar Publications. ASIN B000Z4DW38.

- Redden RF (Apr 15, 2004). "Understanding Laminitis". The Horse.

- Jackson J (2001). Founder: Prevention & Cure the Natural Way. Star Ridge Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9658007-3-0.