Lanfranc

Lanfranc[lower-alpha 1] (1005 x 1010 – 24 May 1089) was a celebrated Italian jurist who renounced his career to become a Benedictine monk at Bec in Normandy. He served successively as prior of Bec Abbey and abbot of St Stephen in Normandy and then as Archbishop of Canterbury in England, following its Conquest by William the Conqueror.[1] He is also variously known as Lanfranc of Pavia (Italian: Lanfranco di Pavia), Lanfranc of Bec (French: Lanfranc du Bec), and Lanfranc of Canterbury (Latin: Lanfrancus Cantuariensis).

Blessed Lanfranc, O.S.B. | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury | |

Statue of Lanfranc from the exterior of Canterbury Cathedral | |

| Appointed | August 1070 |

| Term ended | 24 May 1089 |

| Predecessor | Stigand |

| Successor | Anselm of Canterbury |

| Other posts | Abbot of Saint-Étienne, Caen |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 15 August 1070 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | between 1005 and 1010 AD Pavia, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 24 May 1089 (aged 79-84) Canterbury, Kingdom of England |

| Buried | Canterbury Cathedral, Canterbury, England |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic Church |

| Parents | Hanbald |

Early life

Lanfranc was born in the early years of the 11th century at Pavia, where later tradition held that his father, Hanbald, held a rank broadly equivalent to magistrate. He was orphaned at an early age.[2]

Lanfranc was trained in the liberal arts, at that time a field in which northern Italy was famous (there is little or no evidence to support the myth that his education included much in the way of Civil Law, and none that links him with Irnerius of Bologna as a pioneer in the renaissance of its study). For unknown reasons at an uncertain date, he crossed the Alps, soon taking up the role of teacher in France and eventually in Normandy. About 1039 he became the master of the cathedral school at Avranches, where he taught for three years with conspicuous success. But in 1042 he embraced the monastic profession in the newly founded Bec Abbey. Until 1045 he lived at Bec in absolute seclusion.[3][4]

Teacher and scholar

Lanfranc was then persuaded by Abbot Herluin to open a school at Bec to relieve the monastery's poverty. From the first he was celebrated (totius Latinitatis magister). His pupils were drawn not only from France and Normandy, but also from Gascony, Flanders, Germany and Italy.[5] Many of them afterwards attained high positions in the Church; one possible student, Anselm of Badagio, became pope under the title of Alexander II; another, Anselm of Bec succeeded Lanfranc as the Archbishop of Canterbury. The favourite subjects of his lectures were the trivium of grammar, logic and rhetoric and the application of these principles to theological elucidation. In one of Lanfranc's most important works, The Commentary on the Epistles of St. Paul; he, 'expounded Paul the Apostle; and, wherever opportunity offered, he stated the premises, whether principal or secondary, and the conclusions of Paul's arguments in accordance with the rules of Logic'.[6]

As a result of his growing reputation Lanfranc was invited to defend the doctrine of transubstantiation against the attacks of Berengar of Tours. He took up the task with the greatest zeal, although Berengar had been his personal friend; he was the protagonist of orthodoxy at the Church Councils of Vercelli (1050), Tours (1054) and Rome (1059). To Lanfranc's influence is attributed the desertion of Berengar's cause by Hildebrand and the more broad-minded of the cardinals. Our knowledge of Lanfranc's polemics is chiefly derived from the tract De corpore et sanguine Domini, probably written c. 1060–63.[7] Though betraying no signs of metaphysical ability, his work was regarded as conclusive and became for a while a text-book in the schools. It is often said to be the place where the Aristotelian distinction between substance and accident was first applied to explain Eucharistic change. It is the most important of the surviving works attributed to Lanfranc.[3]

Prior and abbot

In the midst of Lanfranc's scholastic and controversial activities Lanfranc became a political force. Later tradition told that while he was Prior of Bec he opposed the non-canonical marriage of Duke William with Matilda of Flanders (1053) and carried matters so far that he incurred a sentence of exile. Apparently, their relationship was within the prohibited degrees of kindred.[2] But the quarrel was settled when he was on the point of departure, and he undertook the difficult task of obtaining the pope’s approval of the marriage. In this he was successful at the same council which witnessed his third victory over Berengar (1059), and he thus acquired a lasting claim on William's gratitude. In 1066 Lanfranc became the first Abbot of the Abbey of Saint-Étienne at Caen in Normandy, a monastery dedicated to Saint Stephen which the duke had supposedly been enjoined to found as a penance for his disobedience to the Holy See.[3]

Henceforward Lanfranc exercised a perceptible influence on his master's policy. William adopted the Cluniac programme of ecclesiastical reform, and obtained the support of Rome for his English expedition by assuming the attitude of a crusader against schism and corruption. It was Alexander II, possibly a pupil of Lanfranc's and certainly a close friend, who gave the Norman Conquest the papal benediction—a notable advantage to William at the moment, but subsequently the cause of serious embarrassments.[3]

Archbishop of Canterbury

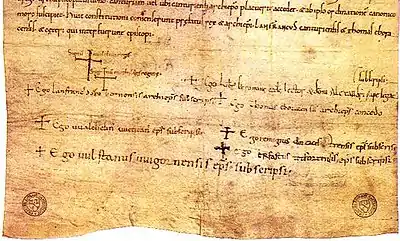

When the see of Rouen next fell vacant (1067), the thoughts of the electors turned to Lanfranc. But he declined the honour, and he was nominated to the English Primacy as Archbishop of Canterbury as soon as Stigand had been canonically deposed on 15 August 1070. He was speedily consecrated on 29 August 1070.[8] The new archbishop at once began a policy of reorganisation and reform. His first difficulties were with Thomas of Bayeux, Archbishop-elect of York, (another former pupil) who asserted that his see was independent of Canterbury and claimed jurisdiction over the greater part of the English Midlands. This was the beginning of a long running dispute between the sees of Canterbury and York, usually known as the Canterbury–York dispute.[9]

Lanfranc, during a visit which he paid the pope for the purpose of receiving his pallium, obtained an order from Alexander that the disputed points should be settled by a council of the English Church. This was held at Winchester in 1072.[3] At this council Lanfranc obtained the confirmation of his primacy that he sought; nonetheless he was never able to secure its formal confirmation by the papacy, possibly as a result of the succession of Pope Gregory VII to the papal throne in 1073.

Lanfranc assisted William in maintaining the independence of the English Church; and appears at one time to have favoured the idea of maintaining a neutral attitude on the subject of the quarrels between papacy and empire. In the domestic affairs of England the archbishop showed more spiritual zeal. His grand aim was to extricate the Church from the fetters of corruption. He was a generous patron of monasticism. He endeavoured to enforce celibacy upon the secular clergy.[3]

Lanfranc obtained the king's permission to deal with the affairs of the Church in synods. In the cases of Odo of Bayeux (1082) (see Trial of Penenden Heath) and of William of St Calais, Bishop of Durham (1088), he used his legal ingenuity to justify the trial of bishops before a lay tribunal.[3]

Lanfranc accelerated the process of substituting Normans for Englishmen in all preferments of importance; and although his nominees were usually respectable, it cannot be said that all of them were better than the men whom they superseded. For this admixture of secular with spiritual aims there was considerable excuse. By long tradition the primate was entitled to a leading position in the king’s councils; and the interests of the Church demanded that Lanfranc should use his power in a manner not displeasing to the king. On several occasions when William I was absent from England Lanfranc acted as his vicegerent.[3]

Lanfranc's greatest political service to the Conqueror was rendered in 1075, when he detected and foiled the conspiracy which had been formed by the earls of Norfolk and Hereford. Waltheof, 1st Earl of Northumberland, one of the rebels, soon lost heart and confessed the conspiracy to Lanfranc, who urged Earl Roger, the earl of Hereford to return to his allegiance, and finally excommunicated him and his adherents. He interceded for Waltheof’s life and to the last spoke of the earl as an innocent sufferer for the crimes of others; he lived on terms of friendship with Bishop Wulfstan of Worcester.[3]

.jpg.webp)

On the death of the Conqueror in 1087 Lanfranc secured the succession for William Rufus, in spite of the discontent of the Anglo-Norman baronage; and in 1088 his exhortations induced the English militia to fight on the side of the new sovereign against Odo of Bayeux and the other partisans of Duke Robert. He exacted promises of just government from Rufus, and was not afraid to remonstrate when the promises were disregarded. So long as he lived he was a check upon the worst propensities of the king’s administration. But his restraining hand was too soon removed. In 1089 he was stricken with fever and he died on 24 May[8] amidst universal lamentations. Notwithstanding some obvious moral and intellectual defects, he was the most eminent and the most disinterested of those who had co-operated with William I in riveting Norman rule upon the English Church and people. As a statesman he did something to uphold the traditional ideal of his office; as a primate he elevated the standards of clerical discipline and education. Conceived in the spirit of popes such as Pope Leo IX, his reforms led by a natural sequence to strained relations between Church and State; the equilibrium which he established was unstable, and depended too much upon his personal influence with the Conqueror.[3]

Not quite sainthood

The efforts of Christ Church Canterbury to secure him the status of saint seem to have had only spasmodic and limited effect beyond English Benedictine circles. However, in the period after the Council of Trent Lanfranc's name was included in the Roman Martyrology, and in the current edition maintains the rank of beatus,[10] the feast day being celebrated on 28 May.[11]

Modern Commemoration

In 1931, the Archbishop Lanfranc School (now The Archbishop Lanfranc Academy) was opened in Croydon, where he had resided at Croydon Palace. Canterbury Christ Church University have named their accommodation block Lanfranc House. He is also remembered in road names in London and Worthing, West Sussex.

Sources

The chief authority is the Vita Lanfranci by the monk Milo Crispin, who was precentor at Bec and died in 1149. Milo drew largely upon the Vita Herluini, composed by Gilbert Crispin, Abbot of Westminster. The Chronicon Beccensis abbatiae, a 14th-century compilation, should also be consulted. The first edition of these two sources, and of Lanfranc's writings, is that of L. d'Achery, Beati Lanfranci opera omnia (Paris, 1648). Another edition, slightly enlarged, is that of J. A. Giles, Lanfranci opera (2 vols., Oxford, 1844). The correspondence between Lanfranc and Pope Gregory VII is given in the Monumenta Gregoriana (ed. P. Jaffi, Berlin, 1865).[3] A more modern edition (and translation) of Lanfranc's correspondence is to be found in H. Clover and M. Gibson (eds), The Letters of Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury (Oxford, 1979). His On the Body and Blood of the Lord is translated (along with Guitmund of Aversa's tract on the same matter) in volume 10 of the Fathers of the Church Medieval Continuation (Washington, DC, 2009).

See also

Citations

- "Lanfranc." The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. 2012. Web. 22 Oct. 2012.

- Birt, Henry Norbert (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Davis 1911.

- Dudley, Leonard (2008). Information Revolutions in the History of the West. Cheltenham: Elgar. p. 53. ISBN 9781848442801. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- Vita Heluini, in Gilbert Crispin, The Works of Gilbert Crispin, Abbot of Westminster, ed. A.S. Abalufia and G.R. Evans, Auctores Britannici Medii Aevi(1986), pp. 194–97

- Sigebert of Gembloux, Liber de Scriptoribus Ecclesiasticised. J.P. Migne, Patrologia Latina vol. 160, cols, 582-3, 'Paulum apostolum exposuit Lanfrancus, et ubicumque opportunitas locorum occurrit, secundum leges dialecticae proponit, assumit, concludit. Richard Southern, Saint Anselm: a Portrait in a Landscape (Cambridge, 1993), p. 40

- Southern, Saint Anselm, p. 44, n. 7 discusses various possible dates

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 232. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Barlow, Frank (1979). The English Church 1066–1154: A History of the Anglo-Norman Church. New York: Longman. pp. 39–42. ISBN 0-582-50236-5.

- Martyrologium Romanum, ex decreto sacrosancti oecumenici Concilii Vaticani II instauratum auctoritate Ioannis Pauli Pp. II promulgatum, editio [typica] altera, Typis Vaticanis, A.D. MMIV (2004), p. 308

- Farmer, David Hugh (2004). Oxford Dictionary of Saints (Fifth ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 309–310. ISBN 978-0-19-860949-0.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Davis, Henry William Carless (1911). "Lanfranc". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 169–170.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Davis, Henry William Carless (1911). "Lanfranc". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 169–170.

Further reading

- LePatourel, John (September 1946). "The Date of the Trial on Penenden Heath". The English Historical Review. 61 (241): 378–388. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXI.CCXLI.378.

| Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Stigand |

Archbishop of Canterbury 1070–1089 |

Succeeded by Anselm of Canterbury (in 1093) |