Lenin's Testament

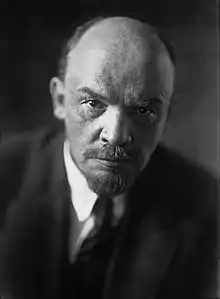

Lenin's Testament is the name given to a document dictated by Vladimir Lenin in the final weeks of 1922 and the first week of 1923. In the testament, Lenin proposed changes to the structure of the Soviet governing bodies. Sensing his impending death, he also gave criticism of Bolshevik leaders Zinoviev, Kamenev, Trotsky, Bukharin, Pyatakov and Stalin. He warned of the possibility of a split developing in the party leadership between Trotsky and Stalin if proper measures were not taken to prevent it. In a post-script he also suggested Joseph Stalin be removed from his position as General Secretary of the Russian Communist Party's Central Committee.

| Lenin's Testament | |

|---|---|

| |

| Created | Final weeks of 1922 and the first week of 1923 |

| Presented | January 1924 |

| Author(s) | Vladimir Lenin |

| Subject | Future leadership of the Soviet Union |

Circumstances surrounding dictation

Scholars have actively discussed the circumstances surrounding the creation of the testament and how these circumstances may have impacted the document. These include Lenin's conflict with Stalin and his declining physical health, deteriorating mental state, and emotional frustration with his condition.

Document history

Lenin wanted the testament to be read out at the 12th Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, to be held in April 1923.[1] However, after Lenin's third stroke in March 1923 that left him paralyzed and unable to speak, the testament was kept secret by his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, in the hope of Lenin's eventual recovery. She possessed four copies while Maria Ulyanova, Lenin's sister, had one. It was only after Lenin's death, on January 21, 1924, that she turned the document over to the Communist Party Central Committee Secretariat and asked for it to be made available to the delegates of the 13th Party Congress in May 1924. Krupskaya wanted the document circulated as widely as possible, in hopes of humiliating Stalin.[2][3]

An edited version of the testament was printed in December 1927 in a limited edition made available to 15th Party Congress delegates. The case for making the testament more widely available was undermined by the consensus within the party leadership that it could not be printed publicly as it would damage the party as a whole.

The text of the testament and the fact of its concealment soon became known in the West, especially after the circumstances surrounding the controversy were described by Max Eastman in Since Lenin Died (1925). The Soviet leadership denounced Eastman's account and used party discipline to force Trotsky, then still a member of the Politburo, to write an article (see the quote from Bolshevik) denying Eastman's version of the events.

The full English text of Lenin's testament was published as part of an article by Eastman that appeared in The New York Times in 1926.[4]

From the time that Stalin consolidated his position as the unquestioned leader of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union, in the late 1920s, all references to Lenin's testament were considered anti-Soviet agitation and punishable as such. The denial of the existence of Lenin's testament remained one of the cornerstones of historiography in the Soviet Union until Stalin's death on March 5, 1953. After Nikita Khrushchev's On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences, at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party, in 1956, the document was finally published officially by the Soviet government.

The original letter is in a museum dedicated to Lenin.

Related documents

This term is not to be confused with "Lenin's Political Testament", a term used in Leninism to refer to a set of letters and articles dictated by Lenin during his illness on how to continue the construction of the Soviet state. Traditionally, it includes the following works:

- A Letter to a Congress, "Письмо к съезду"

- About Assigning of Legislative Functions to Gosplan, "О придании законодательных функций Госплану"

- To the "Nationalities Issue" or about "Autonomization", "К 'вопросу о национальностях' или об 'автономизации' "

- Pages from the Diary, "Странички из дневника"

- About Cooperation, "О кооперации"

- About Our Revolution, "О нашей революции"

- How shall We Reorganise the Rabkrin, "Как нам реорганизовать Рабкрин"

- Better Less but Better, "Лучше меньше, да лучше"

Contents

The letter is a critique of the Soviet government as it then stood. It warned of dangers that he anticipated and made suggestions for the future. Some of those suggestions included increasing the size of the Party's Central Committee, giving the State Planning Committee legislative powers and changing the nationalities policy, which had been implemented by Stalin.

Stalin and Trotsky were criticised:

Comrade Stalin, having become Secretary-General, has unlimited authority concentrated in his hands, and I am not sure whether he will always be capable of using that authority with sufficient caution. Comrade Trotsky, on the other hand, as his struggle against the C.C. on the question of the People's Commissariat of Communications has already proved, is distinguished not only by outstanding ability. He is personally perhaps the most capable man in the present C.C., but he has displayed excessive self-assurance and shown excessive preoccupation with the purely administrative side of the work. These two qualities of the two outstanding leaders of the present C.C. can inadvertently lead to a split, and if our Party does not take steps to avert this, the split may come unexpectedly.

Lenin felt that Stalin had more power than he could handle and might be dangerous if he was Lenin's successor. In a postscript written a few weeks later, Lenin recommended Stalin's removal from the position of General Secretary of the Party:

Stalin is too coarse and this defect, although quite tolerable in our midst and in dealing among us Communists, becomes intolerable in a Secretary-General. That is why I suggest that the comrades think about a way of removing Stalin from that post and appointing another man in his stead who in all other respects differs from Comrade Stalin in having only one advantage, namely, that of being more tolerant, more loyal, more polite and more considerate to the comrades, less capricious, etc. This circumstance may appear to be a negligible detail. But I think that from the standpoint of safeguards against a split and from the standpoint of what I wrote above about the relationship between Stalin and Trotsky it is not a [minor] detail, but it is a detail which can assume decisive importance.

By power, Trotsky argued Lenin meant administrative power, rather than political influence, within the party. Trotsky pointed out that Lenin had effectively accused Stalin of a lack of loyalty.

In the 30 December 1922 article, Nationalities Issue, Lenin criticized the actions of Felix Dzerzhinsky, Grigoriy Ordzhonikidze and Stalin in the Georgian Affair by accusing them of "Great Russian chauvinism".

I think that a fatal role was played here by hurry and the administrative impetuousness of Stalin and also his infatuation with the renowned "social-nationalism". Infatuation in politics generally and usually plays the worst role.

Lenin also criticised other Politburo members:

[T]he October episode with Zinoviev and Kamenev [their opposition to seizing power in October 1917] was, of course, no accident, but neither can the blame for it be laid upon them personally, any more than non-Bolshevism can upon Trotsky.

Finally, he criticised two younger Bolshevik leaders, Bukharin and Pyatakov:

They are, in my opinion, the most outstanding figures (among the younger ones), and the following must be borne in mind about them: Bukharin is not only a most valuable and major theorist of the Party; he is also rightly considered the favorite of the whole Party, but his theoretical views can be classified as fully Marxist only with the great reserve, for there is something scholastic about him (he has never made a study of dialectics, and, I think, never fully appreciated it).

As for Pyatakov, he is unquestionably a man of outstanding will and outstanding ability, but shows far too much zeal for administrating and the administrative side of the work to be relied upon in a serious political matter.

Both of these remarks, of course, are made only for the present, on the assumption that both these outstanding and devoted Party workers fail to find an occasion to enhance their knowledge and amend their one-sidedness.

Isaac Deutscher, a biographer of both Trotsky and Stalin, wrote, "The whole testament breathed uncertainty".[5]

Questions surrounding the content

One puzzling question is why Pyatakov was listed as one of the six major figures of the Communist Party in 1923. Pyatakov was a senior figure as deputy Chairman of the Supreme Council of the National Economy of the Soviet Union, but he was not a major decision maker. The answer may be found in Louis Fischer's Life of Lenin. Pyatakov was a frequent visitor to Lenin's home while he was away from Moscow recuperating. The occasion of the visits was to play the piano selections that Lenin loved since Pyatakov was an accomplished pianist. The close and frequent contact at the time that Lenin composed the letter may be the answer.

Political impact and repercussions

Short term

Lenin's testament presented the ruling triumvirate or troika (Joseph Stalin, Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev) with an uncomfortable dilemma. On the one hand, they would have preferred to suppress the testament since it was critical of all three of them as well as of their ally Nikolai Bukharin and their opponents, Leon Trotsky and Georgy Pyatakov. Although Lenin's comments were damaging to all of the communist leaders, Joseph Stalin stood to lose the most since the only practical suggestion in the testament was to remove him from the position of the General Secretary of the Party's Central Committee.[3]

On the other hand, the leadership dared not go directly against Lenin's wishes so soon after his death, especially with his widow insisting on having them carried out. The leadership was also in the middle of a factional struggle over the control of the Party, the ruling faction being loosely allied groups that would soon part ways, which would have made a coverup difficult.

The final compromise proposed by the triumvirate at the Council of the Elders of the 13th Congress after Kamenev read out the text of the document was to make Lenin's testament available to the delegates on the following conditions (first made public in a pamphlet by Trotsky published in 1934 and confirmed by documents released during and after glasnost):

- The testament would be read by representatives of the party leadership to each regional delegation separately.

- Taking notes would not be allowed.

- The testament would not be referred to during the plenary meeting of the Congress.

The proposal was adopted by a majority vote, over Krupskaya's objections. As a result, the testament did not have the effect that Lenin had hoped for, and Stalin retained his position as General Secretary, with the notable help of Aleksandr Petrovich Smirnov, then People’s Commissar of Agriculture.[6]

Long term

Failure to make the document more widely available within the party remained a point of contention during the struggle between the Left Opposition and the Stalin-Bukharin faction in 1924 to 1927. Under pressure from the opposition, Stalin had to read the testament again at the July 1926 Central Committee meeting.

Authenticity dispute

Historian Stephen Kotkin, in his biography of Stalin, argues that Lenin's authorship of the Testament "must [be] treat[ed] with caution"[7] and suggests that it was more likely authored by Nadezhda Krupskaya. Kotkin pointed out that the purported dictations were not logged in the customary manner by Lenin's secretariat at the time they were supposedly given; that they were typed, with no shorthand or stenographic originals in the archives, and that Lenin did not initial them;[8][9] that by the alleged dates of the dictations, Lenin had lost much of his power of speech following a series of small strokes on December 15-16, 1922, raising questions about his ability to dictate anything as detailed and intelligible as the Testament[10][11] and that the dictation purportedly given in December 1922 is suspiciously responsive to debates that took place at the 12th Party Congress in April 1923.[12]

As for the attribution to Krupskaya, Kotkin says that given her central role in Lenin's care and his communication with the outside world, she had to have been involved in creating the documents. He argued that Krupskaya may have been attempting to achieve a balance between Lenin's possible successors by bringing forward the spurious dictations at critical moments during the unfolding succession struggle.[13]

Kotkin argues that regardless of its true author, the Testament was treated as authentic by the Party leadership at the time and so it had profound political consequences for Stalin.[7]

However this view is not widely accepted. The Testament has been accepted as genuine by the large majority of historians, including E. H. Carr, Isaac Deutscher, Dmitri Volkogonov, Vadim Rogovin and Oleg Khlevniuk.[14][15] Kotkin's claims were also rejected by Richard Pipes soon after they were published. [16]

References

Notes

Citations

- The New Cambridge Modern History, Volume XII. CUP Archive. p. 453. GGKEY:Q5W2KNWHCQB.

- Sebesteyn, Victor (2017). Lenin the Dictator. Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 9781474600460.

- Felshtinsky, Yuri; Litvinenko, Alexander (October 26, 2010). Lenin and His Comrades: The Bolsheviks Take Over Russia 1917-1924. New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 9781929631957.

- Eastman, Max (October 18, 1926). "Lenin's 'Testament' at Last Revealed". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Isaac Deutscher, "Stalin – a Political Biography", 2nd edition, 1967, English ISBN 978-0195002737, pp. 248–251

- Trotsky, Leon. "Leon Trotsky: On Lenin's Testament (1932)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- Kotkin 2014, p. 473.

- Kotkin 2014, p. 498.

- Kotkin 2014, p. 505.

- Kotkin 2014, p. 483.

- Kotkin 2014, p. 489.

- Kotkin 2014, p. 500.

- Kotkin 2014, p. 501.

- White, Fred (June 1, 2015). "A review of Stephen Kotkin's Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928". World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- Gessen, Keith (October 30, 2017). "How Stalin Became a Stalinist". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- Richard Pipes, “The Cleverness of Joseph Stalin,” New York Review of Books, November 20, 2014.

Bibliography

Books

- Kotkin, Stephen (2014). Stalin: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9944-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Journals

- Lih, Lars T. (1991). "Political Testament of Lenin and Bukharin and the Meaning of NEP". Slavic Review. 50 (2): 241–252. doi:10.2307/2500200. ISSN 2325-7784. JSTOR 2500200.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Newspapers

- Adams, J. Donald (July 12, 1925). "Lenin Betrayed By His Party; His "Testament," Praising Trotsky and Attacking Stalin-Zinovieff Group, Was Suppressed". New York Times.

- Duranty, Walter (November 3, 1927). "Stalin and Trotsky in Furious Debate". New York Times.

External links

- Lenin's Last Testament (text)

- On the suppressed Testament of Lenin by Leon Trotsky (written in December 1932, published in 1934, sometimes incorrectly dated as 1926)