Tito–Stalin split

The Tito–Stalin split, or the Yugoslav–Soviet split, was the culmination of a conflict between the political leaderships of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, especially under Josip Broz Tito and Joseph Stalin, in the years following World War II. Although presented by both sides as an ideological dispute, the conflict was the product of a geopolitical struggle in the Balkans that also involved Albania, Bulgaria, and the communist insurgency in Greece, which Yugoslavia supported and the Soviet Union opposed.

In the years following World War II, Yugoslavia pursued economic, internal, and foreign policy objectives that did not align with the interests of the Soviet Union and its Eastern Bloc allies. Tito's plans to admit neighbouring Albania to the Yugoslav federation exacerbated the tensions. Yugoslav support of the communist rebels in Greece further complicated the political situation. Yugoslavia provided this to pursue possible territorial expansion by fostering an atmosphere of insecurity within the Albanian political leadership. The Soviets opposed the Yugoslav policy towards Greece and made efforts to slow down Yugoslav–Albanian integration. Stalin tried to pressure and moderate Yugoslavia via Bulgaria. When the conflict between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union became public in 1948, it was portrayed as an ideological dispute to avoid the impression of a power struggle within the Eastern Bloc.

The split ushered in the Informbiro period of purges within the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. It was accompanied by a significant level of disruption to the Yugoslav economy, which had previously depended on the Eastern Bloc. The conflict also prompted fears of an impending Soviet invasion. Deprived of aid from the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, Yugoslavia subsequently turned to the United States for economic and military assistance.

Background

| Eastern Bloc |

|---|

|

Tito–Stalin conflict during World War II

During World War II, the alliances of the Soviet Union (USSR), Stalin's desire to expand the Soviet sphere of influence beyond the borders of the USSR, and the confrontation between the Tito-led Communist Party of Yugoslavia (Serbo-Croatian: Komunistička partija Jugoslavije, KPJ) and the Yugoslav government-in-exile headed by King Peter II of Yugoslavia complicated the relationship between Josip Broz Tito and Joseph Stalin.[1]

The Axis powers invaded the Kingdom of Yugoslavia on 6 April 1941. The country surrendered 11 days later, and the government fled abroad, ultimately relocating to London. Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, Bulgaria and Hungary annexed parts of the country. The remaining territory was broken up into several parts: the east was divided into the German-occupied areas of Serbia and Banat, while the west became the Independent State of Croatia (Croatian: Nezavisna država Hrvatska, NDH), a puppet state garrisoned by German and Italian forces.[1] The USSR, still honouring the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, broke off relations with the Yugoslav government and sought, through its intelligence assets, to set up a new Communist organisation independent of the KPJ in the NDH. The USSR also tacitly approved the restructuring of the Bulgarian Workers’ Party (Bulgarian: Българска работническа партия). In particular, the party's new organisational structure and territory of operation were adjusted to account for annexation of Yugoslav territories by Bulgaria. The USSR only reversed its support for such actions in September 1941—well after the start of the Axis invasion of the USSR—after repeated protests from the KPJ.[2]

In June 1941, Tito informed the Comintern and Stalin about his plans for an uprising against the Axis occupation. However, Stalin saw the prolific use of Communist symbols by the Yugoslav Partisans as problematic.[3] This was because Stalin viewed his alliance with the United Kingdom and the United States as necessarily contrary to the Axis destruction of "democratic liberties". Stalin thus felt the Communist forces in Axis occupied Europe were actually obligated to fight to restore democratic liberties—even if temporarily. In terms of Yugoslavia, this meant that Stalin expected the KPJ to fight to restore the government in exile. Remnants of the Royal Yugoslav Army, led by Army General Draža Mihailović and organised as Chetnik guerrillas, were already pursuing the restoration of King Peter II.[4]

In October 1941, Tito met Mihailović twice to propose a joint struggle against the Axis. Tito offered him the position of chief of staff of the Partisan forces, but Mihailović turned down the offer.[5] By the end of the month, Mihailović concluded that the Communists were the true enemy. At first, Mihailović's Chetniks fought the Partisans and the Axis forces simultaneously, but within months, they began collaborating with the Axis against the Partisans.[6] By November, the Partisans were fighting the Chetniks while sending messages to Moscow protesting Soviet propaganda praising Mihailović.[5]

In 1943, Tito transformed the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (Serbo-Croatian: Antifašističko vijeće narodnog oslobođenja Jugoslavije, AVNOJ) into an all-Yugoslav deliberative and legislative body, denounced the government in exile, and forbade the return of the king to the country. These decisions ran against explicit Soviet advice instructing Tito not to antagonise the exiled government and Peter II. Stalin was at the Tehran Conference at the time and viewed the move as a betrayal of the USSR.[7] In 1944–1945, Stalin's renewed instructions to Communist leaders in Europe to establish coalitions with bourgeois politicians were met with incredulity in Yugoslavia.[8] This shock was reinforced by the Percentages Agreement, which Stalin revealed to the surprised Edvard Kardelj, vice president of the Yugoslav provisional government.[9]

In the final days of the war, the Partisans captured parts of Carinthia in Austria and were advancing across pre-war Italian soil. While the Western Allies believed Stalin arranged the move,[10] he actually opposed it. Specifically, Stalin feared for the Soviet-backed Austrian government of Karl Renner, and he was afraid that a wider conflict with the Allies over Trieste would ensue.[11] Stalin ordered Tito to withdraw, and the Partisan forces complied.[12]

Political situation in Eastern Europe, 1945–1948

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the USSR sought to establish its political dominance in the areas beyond its borders that had come under the control of the Red Army. This objective was pursued largely through the establishment of coalition governments in Eastern European countries. Outright Communist rule was generally difficult to achieve because Communist parties were usually quite small. The Communist leaders saw the strategic approach as a temporary measure until circumstances allowing for sole Communist rule improved.[13]

The Yugoslav and Albanian Communist parties each had significant bases grown on the support of Tito's Partisan movement in Yugoslavia and Albania's National Liberation Movement.[14] While Tito's Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia was under Soviet influence in the final months of the war and the first few post-war years, Stalin declared it outside the Soviet sphere of interest on several occasions,[15] treating it like a Yugoslav satellite state.[16]

The contrast with the rest of Eastern Europe was underscored ahead of a Soviet offensive in October 1944. Tito's partisans supported the offensive, which ultimately pushed the Wehrmacht and its allies out of northern Serbia and captured Belgrade.[17] However, Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin's Third Ukrainian Front had to request formal permission from Tito's provisional government to enter Yugoslavia and accept Yugoslav civil authority in any liberated territory.[18]

Deteriorating relations

Yugoslav foreign policy, 1945–1947

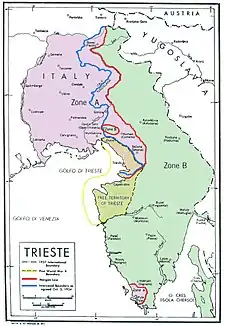

After the war, the USSR and Yugoslavia signed a friendship treaty when Tito met with Stalin in Moscow in 1945.[11] They established good bilateral relations which Yugoslav domestic and foreign policies did not appear to seriously affect. Although the KPJ pursued the goal of a communist or socialist society in a way that sometimes differed from the Soviet model, the differences were only in method, not in objective.[19] In 1945, Yugoslavia relied on United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration aid as it experienced food shortages, but it gave much greater internal publicity to comparably smaller Soviet assistance.[20] Nonetheless, in 1945, Stalin complained that Yugoslavia's foreign policy was unreasonable because of its territorial claims against most of its neighbours.[21] (Yugoslavia had made claims against Hungary,[22] Austria,[23] and the Free Territory of Trieste, which had been carved out of pre-war Italian territory.[24]) Tito then gave a speech criticising the USSR, alleging inadequate Soviet backing of his territorial demands.[20] The confrontation with the Western Allies became tense in August 1946 when Yugoslav fighters forced a United States Army Air Forces Douglas C-47 Skytrain to crash-land near Ljubljana and shot down another above Bled, capturing ten and killing a crew of five in a space of ten days.[25] The Western Allies incorrectly believed that Stalin encouraged Tito's persistence; Stalin actually wished to avoid confrontation with the West over the issue.[12]

Tito also sought to establish regional dominance over Yugoslavia's southern neighbours—Albania, Bulgaria, and Greece. The first overtures in this direction occurred in 1943, when a proposal for a regional headquarters to coordinate national Partisan actions fell through. Tito, who saw the Yugoslav component of the Partisans as superior, declined to go ahead with any scheme that would give other national components equal say. The pre-war partition of the contested region of Macedonia into three sections—Vardar, Pirin, and Aegean Macedonia—controlled by Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Greece respectively complicated regional relations. The presence of a substantial ethnic Albanian population in the Yugoslav region of Kosovo further impeded relations. In 1943, the Communist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Komuniste e Shqipërisë, PKSH) proposed the transfer of Kosovo to Albania, only to be confronted with a counterproposal: incorporating Albania into the future Yugoslav federation.[26] Tito and the PKSH first secretary, Enver Hoxha, revisited the idea in 1946, agreeing on the inevitability of the merger of the two countries.[27]

After the war, Tito continued to pursue dominance in the region. In 1946, Albania and Yugoslavia signed a treaty on mutual assistance and customs agreements, almost completely integrating Albania into the Yugoslav economic system. Nearly a thousand Yugoslav economic development experts were sent to Albania, and KPJ representative was added to the PKSH central committee.[28] The two countries' militaries also cooperated, at least in the mining of the Corfu Channel in October 1946—an action which damaged two Royal Navy destroyers and resulted in 44 dead and 42 injured.[29] Even though the USSR had indicated previously it would only deal with Albania through Yugoslavia, Stalin cautioned the Yugoslavs to slow down unification with Albania.[28]

In August 1947, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia signed a friendship and mutual assistance treaty in Bled without consulting the USSR, leading Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov to denounce it.[30] Despite this, when the Cominform was established in September to facilitate international Communist activity and communication,[31] the Soviets openly touted Yugoslavia as a model for the Eastern Bloc to emulate.[32] Since 1946, however, internal reports from the Soviet embassy in Belgrade had portrayed Yugoslav leaders in increasingly unfavourable terms.[33]

Integration with Albania and support for Greek insurgents

The USSR began sending its own advisors to Albania in mid-1947. Tito saw this as a threat to the further integration of Albania into Yugoslavia. He also attributed the move to a power struggle within the PKSH central committee involving Hoxha, the interior minister Koçi Xoxe, and the economy and industry minister, Naco Spiru. Spiru was seen as the prime opponent of links with Yugoslavia and of direct ties between Albania and the USSR. Prompted by Yugoslav accusations, and urged on by Xoxe, Hoxha launched an investigation into Spiru. A few days later, Spiru died in unclear circumstances. His death was officially declared a suicide.[34]

Following Spiru's death, there were a series of meetings of Yugoslav and Soviet diplomats and officials on the matter of integration, culminating in a meeting between Stalin and KPJ official Milovan Đilas in December 1947 and January 1948. By its conclusion, Stalin supported the integration of Albania into Yugoslavia, provided it was postponed until an appropriate moment and carried out with the consent of Albanians. It is still debated if Stalin was sincere in his support, or if he was pursuing a delaying tactic. Regardless, Đilas perceived Stalin's support as genuine.[35]

Yugoslav support to the Democratic Army of Greece (Greek: Δημοκρατικός Στρατός Ελλάδας, Dimokratikós Stratós Elládas, DSE) in the Greek Civil War indirectly fostered Albanian support for closer ties with Yugoslavia. The armed clashes there were reinforcing the Albanian perception that the Yugoslav and Albanian borders were being threatened by Greece.[36] Furthermore, there was an US intelligence-gathering operation in the country,[37] and an airdrop of twelve British Secret Intelligence Service-trained agents in 1947 Operation Valuable. The agents were deployed in central Albania to start an insurrection which did not materialise.[38] The Yugoslavs hoped this perception would lead to increased Albanian support for integration with Yugoslavia. Soviet envoys to Albania deemed the effort successful in instilling Albanians with a fear of Greeks along with a perception that Albania could not defend itself on its own.[36] At the same time, Soviet sources indicated there was no actual threat of a Greek invasion of Albania.[39] Tito thought there was another potential benefit from his support to the DSE. Many DSE fighters were Macedonian Slavs leading Tito to believe that cooperating with the DSE might allow Yugoslavia to annex Greek territory by expanding into Aegean Macedonia even if the DSE failed to seize power.[36]

Shortly after Đilas and Stalin met, Tito suggested to Hoxha that Albania should permit Yugoslavia to use military bases near Korçë, close to the Albanian–Greek border, to defend against potential Greek and Anglo–American attack. By the end of January, Hoxha accepted the idea. Moreover, Xoxe indicated that the integration of Albanian and Yugoslav armies was approved. Even though the matter was supposedly conducted in secrecy, the Soviets learned of the scheme from a source in the Albanian government.[40]

Federation with Bulgaria

In late 1944, Stalin first proposed a Yugoslav–Bulgarian federation, likely to temper Tito's policies. The proposal involved a dualist state where Bulgaria would be one half of the federation and Yugoslavia (further divided into its republics) the other. The Yugoslav position was the federation was possible, but only if Bulgaria were one of its seven members, and if Pirin Macedonia was ceded to the nascent Yugoslav federal unit of Macedonia. Since the two sides could not agree, Stalin invited them to Moscow in January 1945 for arbitration—first supporting the Bulgarian view—and days later switching to the Yugoslav position. Finally, on 26 January, the British government warned the Bulgarian authorities against any federation arrangement with Yugoslavia before Bulgaria signed a peace treaty with the Allies. Thus, the idea was shelved, to the relief of Tito.[41]

Three years later, in 1948, in the same period when Tito and Hoxha were arranging for the deployment of the Yugoslav People's Army to Albania, Bulgarian Workers' Party leader Georgi Dimitrov spoke to Western journalists about turning the Eastern Bloc into a federally organised state. He then included Greece in a list of "people's democracies" causing concern in the West and in the USSR. Tito sought to distance Yugoslavia from the idea as damaging, but the USSR interpreted Dimitrov's words as influenced by Yugoslav intentions in the Balkans. Nonetheless, on 1 February 1948, Molotov instructed Yugoslav and Bulgarian leaders to send representatives to Moscow by 10 February for discussions.[42] On 5 February, just days before scheduled meeting with Stalin, the DSE launched its general offensive, shelling Thessaloniki four days later.[43]

February 1948 meeting with Stalin

In response to Molotov's summons, Tito dispatched Kardelj and Vladimir Bakarić to Moscow, where they joined Đilas. Stalin berated the Yugoslavs and Dimitrov for ignoring the USSR in the signing of the Bled Agreement and for Dimitrov's call to include Greece in a hypothetical federation with Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. He also demanded an end to the insurrection in Greece, arguing that any further support for the Communist guerrillas there might lead to a wider conflict with the United States and the British.[43] By limiting his support to the DSE, Stalin adhered to the Percentages Agreement which placed Greece in the British sphere of influence.[44]

Stalin also demanded an immediate federation consisting of Bulgaria and Yugoslavia.[45] According to Stalin, Albania would only later join such a federation. At the same time, he expressed support for similar unions of Hungary and Romania and of Poland and Czechoslovakia. Yugoslav and Bulgarian participants in the meeting acknowledged mistakes, and Stalin made Kardelj and Dimitrov sign a treaty obliging Yugoslavia and Bulgaria to consult the Soviet Union on all foreign policy matters.[46]

In response to the Moscow meeting, the KPJ politburo met in secret on 19 February and decided against any federation with Bulgaria. Two days later, Tito, Kardelj, and Đilas met with Nikos Zachariadis, the general secretary of the Communist Party of Greece (Greek: Κομμουνιστικό Κόμμα Ελλάδας, KKE). They informed Zachariadis that Stalin was opposed to the KKE's armed struggle but promised continued Yugoslav support, nonetheless.[47]

The KPJ central committee met on 1 March and noted that Yugoslavia would remain independent only if it resisted Soviet designs for economic development of the Eastern Bloc.[48] (The USSR viewed the Yugoslav five-year development plan unfavourably because it did not align with the needs of the Eastern Bloc but prioritised development based solely on local development needs.[49]) The central committee also dismissed the possibility of federation with Bulgaria, interpreting it as a form of Trojan Horse tactic. The committee finally decided to proceed with the existing policy towards Albania.[48] Unlike the meeting on 19 February, politburo member and government minister Sreten Žujović attended this one, and informed the Soviets about what had transpired.[33]

In Albania, Xoxe purged all anti-Yugoslav forces from the PKSH central committee at a plenum of 26 February–8 March.[50] The PKSH central committee adopted a resolution declaring pro-Yugoslav orientation the official Albanian policy. Albanian authorities adopted an additional secret document detailing a planned merger of Albanian forces with the Yugoslav army. They cited the threat of Greek invasion as a pretext for the move, arguing that having Yugoslav troops at the Albanian-Greek border was an "urgent necessity".[33] In response to those moves, Soviet military advisers were withdrawn from Yugoslavia on 18 March.[50]

Stalin's letters and open conflict

First letter

On 27 March, Stalin sent his first letter, addressed to Tito and Kardelj, which formulated the conflict as an ideological one.[51] In his letter, Stalin denounced Tito and Kardelj, as well as Đilas, Svetozar Vukmanović, Boris Kidrič, and Aleksandar Ranković, as "dubious Marxists" responsible for the anti-Soviet atmosphere in Yugoslavia. Stalin also criticised Yugoslav policies on security, the economy, and political appointments. In particular, he resented the suggestion that Yugoslavia was more revolutionary than the USSR, drawing comparisons to the positions and the fate of Leon Trotsky. The purpose of the letter was to urge loyal Communists to remove the "dubious Marxists".[52] The Soviets maintained contact with Žujović and former minister of industry Andrija Hebrang and, in early 1948, instructed Žujović to oust Tito from office. They hoped to secure the position of the general secretary of the KPJ for Žujović and have Hebrang fill the post of the prime minister.[53]

Tito convened the KPJ central committee on 12 April to draw up a letter in response to Stalin. Tito repudiated Stalin's claims and ascribed them to slander and misinformation. He also emphasised the KPJ's achievements of national independence and equality. Žujović was the only one to oppose Tito at the meeting. He advocated making Yugoslavia a part of the USSR, and he questioned what the country's future position in international relations would be if the Soviet alliance was not maintained.[54] Tito called for action against Žujović and Hebrang. He denounced Hebrang, accusing him of being the primary source of Soviet mistrust. To discredit him, charges were fabricated alleging that Hebrang had become an Ustaše spy during his captivity in 1942 and that he was subsequently blackmailed with that information by the Soviets. Both Žujović and Hebrang were apprehended within a week.[55]

Second letter

On 4 May, Stalin sent the second letter to the KPJ. He denied the Soviet leadership was misinformed about the situation in Yugoslavia and claimed that the differences were over a matter of principle. He also denied Hebrang was a Soviet source in the KPJ but confirmed that Žujović was indeed one. Stalin questioned the scale of KPJ's achievements, alleging that the success of any communist party depended on Red Army assistance—implying the Soviet military was essential to whether or not the KPJ retained power. Finally, he suggested taking the matter up before the Cominform.[56]

In their response to the second letter, Tito and Kardelj rejected arbitration by the Cominform, and accused Stalin of lobbying other communist parties to affect the outcome of the dispute.[57]

Third letter and Cominform Resolution

On 19 May, Tito received an invitation for the Yugoslav delegation to attend a Cominform meeting to discuss the situation concerning the KPJ. However, the KPJ's central committee rejected the invitation the next day. Stalin then sent his third letter, now addressed to Tito and Hebrang, stating that failure to speak on behalf of the KPJ before the Cominform would amount to a tacit admission of guilt. On 19 June, the KPJ received a formal invitation to attend the Cominform meeting in Bucharest in two days. The KPJ leadership informed the Cominform that they would not send any delegates.[58]

The Cominform published its Resolution on the KPJ on 28 June exposing the conflict and criticising the KPJ for anti-Sovietism and ideological errors, lack of democracy in the party, and an inability to accept criticism.[59] Moreover, the Cominform accused the KPJ of opposing the parties within the organisation, splitting from the united socialist front, betraying international solidarity of the working people, and assuming a nationalist posture. Finally, the KPJ was declared outside the Cominform. The resolution claimed there are "healthy" members of the KPJ whose loyalty would be measured by their readiness to overthrow Tito and his leadership—expecting this to be achieved solely because of Stalin's charisma. Stalin expected the KPJ to back down, sacrifice the "dubious Marxists", and realign itself with him.[59]

Aftermath

Faced with the choice of resisting or submitting to Stalin, Tito chose the former—likely counting on the wide organic base of the Communist party built through the Partisan movement to support him. It is estimated that up to 20 percent of the KPJ membership supported Stalin instead of Tito. The Party leadership noticed this, and it led to wide-ranging purges that went far beyond the most visible targets like Hebrang and Žujović. In Yugoslavia this period is known as the Informbiro period, meaning the "Cominform period". The real or perceived supporters of Stalin were termed "Cominformists" or "ibeovci" as a pejorative initialism based on the first two words in the official name of the Cominform—the Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties. Thousands were imprisoned, killed, or exiled.[60] According to Ranković, fifty-one thousand people were killed, imprisoned, or sentenced to forced labour.[61] Numerous sites, including actual prisons and prison camps in Stara Gradiška and the former Ustaše concentration camp in Jasenovac held the prisoners. A special-purpose prison camp was built for Cominformists on the uninhabited Adriatic islands of Goli Otok and Sveti Grgur in 1949.[62]

United States aid to Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia faced significant economic difficulties because of the split, since its planned economy depended on unimpeded trade with the USSR and the Eastern Bloc which ended. A potential war with the USSR led to high military spending—rising to 21.4 percent of the national income in 1952.[63] The United States noted the opportunity to score a Cold War victory, but it employed a cautious approach, unsure if the rift was lasting or if Yugoslav foreign policy would change.[64]

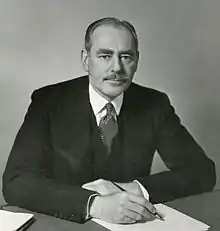

Yugoslavia first requested assistance from the United States in summer 1948.[65] In December, Tito announced strategic raw materials would be shipped to the West in return for increased trade.[66] In February 1949, the US decided to provide Tito with economic assistance. In return, the US demanded cessation of aid to the DSE when the internal situation in Yugoslavia allowed such a move without endangering Tito's position.[67] Ultimately, Secretary of State Dean Acheson took the position that the Yugoslav five-year plan would have to succeed if Tito was to prevail against Stalin. Acheson also argued that supporting Tito was in the interest of the United States, regardless of the nature of Tito's regime.[68] The aid helped Yugoslavia to overcome the poor harvests of 1948, 1949 and 1950,[69] but there would be almost no economic growth before 1952.[70] Tito also received US backing in Yugoslavia's successful 1949 bid for a seat on the United Nations Security Council,[71] against Soviet opposition.[69]

In 1949, the United States provided loans to Yugoslavia, increased them in 1950, and then provided large grants.[72] The Yugoslavs avoided asking for military aid initially, believing it would provide a pretext for a Soviet invasion. However, by 1951, Yugoslav authorities became convinced that Soviet attack was inevitable regardless of any military aid from the West. Consequently, Yugoslavia was included in the Mutual Defense Assistance Program.[73]

Soviet actions and military coup

When the conflict became public in 1948, Stalin embarked upon a propaganda campaign against Tito.[74] The Soviet allies blockaded their borders with Yugoslavia; there were 7,877 border incidents.[75] By 1953, Soviet or Soviet-backed incursions had resulted in the killing of 27 Yugoslav security personnel.[76] It is not clear whether the USSR planned any military intervention against Yugoslavia after the split. Hungarian Major General Béla Király, who defected to the United States in 1956, claimed that there were such plans, but recent research has concluded his claims were false.[77] It is also possible Stalin was dissuaded from intervening by the United States's response to the outbreak of the Korean War.[78] Yugoslavs believed that Soviet invasion was likely or imminent and made defensive plans accordingly.[79] A message Stalin sent to Czechoslovak President Klement Gottwald shortly after the June 1948 Cominform meeting suggests that Stalin's objective was to isolate Yugoslavia—thereby causing its decline—instead of toppling Tito.[80]

In the immediate aftermath of the split, there was at least one failed attempt at a military coup d'état supported by the Soviets. It was headed by Yugoslav army officials: the chief of the General Staff Colonel General Arso Jovanović, Major General Branko Petričević Kadja, and Colonel Vladimir Dapčević. The plot was foiled and border guards killed Jovanović near Vršac while he was attempting to flee to Romania. Petričević was arrested in Belgrade, and Dapčević was arrested just as he was about to cross the Hungarian border.[81] There was also a separate plan to assassinate Tito, which involved options for use of a biological agent and a poison codenamed Scavenger. The Soviet Ministry of State Security prepared the plan in 1952, but Stalin died before it could be executed.[82][83]

In Eastern Bloc politics, the split with Yugoslavia led to the denunciation and prosecution of alleged Titoists designed to strengthen Stalin's control over the bloc's communist parties. They resulted in show trials of high-ranking officials such as Xoxe, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia Rudolf Slánský, Hungarian interior and foreign minister László Rajk, and General Secretary of the Bulgarian Workers' Party central committee Traicho Kostov. Furthermore, Albania and Bulgaria turned away from Yugoslavia and aligned themselves entirely with the USSR.[84] Regardless of DSE dependence on Yugoslav support, the KKE also sided with the Cominform,[85] declaring its support for fragmentation of Yugoslavia and independence of Macedonia.[86] In July 1949, Yugoslavia responded by withholding further support to the Greek guerillas and the DSE collapsed almost immediately.[87][85]

Footnotes

- Banac 1988, p. 4.

- Banac 1988, pp. 4–5.

- Banac 1988, pp. 6–7.

- Banac 1988, p. 9.

- Banac 1988, p. 10.

- Tomasevich 2001, p. 142.

- Banac 1988, p. 12.

- Reynolds 2006, pp. 270–271.

- Banac 1988, p. 15.

- Reynolds 2006, pp. 274–275.

- Banac 1988, p. 17.

- Tomasevich 2001, p. 759.

- Judt 2005, pp. 130–132.

- Perović 2007, p. 59.

- Perović 2007, p. 61.

- McClellan 1969, p. 128.

- Ziemke 1968, pp. 375–377.

- Banac 1988, p. 14.

- Perović 2007, pp. 36–37.

- Ramet 2006, p. 176.

- Judt 2005, p. 129.

- Klemenčić & Schofield 2001, pp. 12–13.

- Ramet 2006, p. 173.

- Judt 2005, p. 142.

- Jennings 2017, pp. 239–240.

- Perović 2007, pp. 42–43.

- Banac 1988, p. 219.

- Perović 2007, pp. 43–44.

- Kane 2014, p. 76.

- Perović 2007, p. 52.

- Judt 2005, p. 143.

- Perović 2007, p. 40.

- Perović 2007, p. 57.

- Perović 2007, pp. 46–47.

- Perović 2007, pp. 47–48.

- Perović 2007, pp. 45–46.

- Lulushi 2014, pp. 121–122.

- Theotokis 2020, p. 142.

- Perović 2007, note 92.

- Perović 2007, pp. 48–49.

- Banac 1988, pp. 31–32.

- Perović 2007, pp. 50–52.

- Banac 1988, p. 41.

- Banac 1988, pp. 32–33.

- Banac 1988, pp. 41–42.

- Perović 2007, p. 55.

- Perović 2007, p. 56.

- Banac 1988, p. 42.

- Lees 1978, p. 408.

- Banac 1988, p. 43.

- Perović 2007, p. 58.

- Banac 1988, pp. 43–45.

- Ramet 2006, p. 177.

- Banac 1988, pp. 117–118.

- Banac 1988, pp. 119–120.

- Banac 1988, p. 123.

- Banac 1988, p. 124.

- Banac 1988, pp. 124–125.

- Banac 1988, pp. 125–126.

- Perović 2007, pp. 58–61.

- Woodward 1995, p. 180, note 37.

- Banac 1988, pp. 247–248.

- Banac 1988, p. 131.

- Lees 1978, pp. 410–412.

- Lees 1978, p. 411.

- Lees 1978, p. 413.

- Lees 1978, pp. 415–416.

- Lees 1978, pp. 417–418.

- Auty 1969, p. 169.

- Eglin 1982, p. 126.

- Woodward 1995, p. 145, note 134.

- Brands 1987, p. 41.

- Brands 1987, pp. 46–47.

- Perović 2007, p. 33.

- Banac 1988, p. 130.

- Banac 1988, p. 228.

- Perović 2007, note 120.

- Ramet 2006, pp. 199–200.

- Perović 2007, pp. 58–59.

- Perović 2007, p. 60.

- Banac 1988, pp. 129–130.

- Ramet 2006, p. 200.

- Jennings 2017, p. 251.

- Perović 2007, pp. 61–62.

- Banac 1988, p. 138.

- Judt 2005, p. 505.

- Judt 2005, p. 141.

References

Books

- Auty, Phyllis (1969). "Yugoslavia's International Relations (1945-1965)". In Vucinich, Wayne S. (ed.). Contemporary Yugoslavia: Twenty Years of Socialist Experiment. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 154–202. ISBN 9780520331105.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Banac, Ivo (1988). With Stalin against Tito: Cominformist Splits in Yugoslav Communism. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2186-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eglin, Darrel R. (1982). "The Economy". In Nyrop, Richard F. (ed.). Yugoslavia, a Country Study (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 113–168. LCCN 82011632.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jennings, Christian (2017). Flashpoint Trieste: The First Battle of the Cold War. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5126-0172-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Judt, Tony (2005). Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. New York, New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 1-59420-065-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kane, Robert B. (2014). "Corfu Channel Incident, 1946". In Hall, Richard C. (ed.). War in the Balkans (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-6106-9030-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klemenčić, Mladen; Schofield, Clive H. (2001). War and Peace on the Danube: The Evolution of the Croatia-Serbia Boundary. Durham, UK: International Boundaries Research Unit. ISBN 9781897643419.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lulushi, Albert (2014). Operation Valuable Fiend: The CIA's First Paramilitary Strike Against the Iron Curtain. New York City, New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 9781628723946.

- McClellan, Woodford (1969). "Postwar Political Evolution". In Vucinich, Wayne S. (ed.). Contemporary Yugoslavia: Twenty Years of Socialist Experiment. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 119–153. ISBN 9780520331105.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253346568.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reynolds, David (2006). From World War to Cold War: Churchill, Roosevelt, and the International History of the 1940s. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199284115.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Theotokis, Nikolaos (2020). Airborne Landing to Air Assault: A History of Military Parachuting. Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 9781526747020.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woodward, Susan L. (1995). Socialist Unemployment: The Political Economy of Yugoslavia, 1945-1990. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08645-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ziemke, Earl F. (1968). Stalingrad to Berlin: The German Defeat in the East. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. LCCN 67-60001.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Journals

- Brands, Henry W. Jr (1987). "Redefining the Cold War: American Policy toward Yugoslavia, 1948–60". Diplomatic History. Oxford University Press. 11 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1987.tb00003.x. ISSN 0145-2096. JSTOR 24911740.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lees, Lorraine M. (1978). "The American Decision to Assist Tito, 1948–1949". Diplomatic History. Oxford University Press. 2 (4): 407–422. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1978.tb00445.x. ISSN 0145-2096. JSTOR 24910127.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perović, Jeronim (2007). "The Tito–Stalin split: a reassessment in light of new evidence". Journal of Cold War Studies. MIT Press. 9 (2): 32–63. doi:10.5167/uzh-62735. ISSN 1520-3972.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Banac, Ivo (1995). "The Tito–Stalin Split and the Greek Civil War". In Iatrides, John O.; Wrigley, Linda (eds.). Greece at the Crossroads: The Civil War and Its Legacy. University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-02568-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dimić, Ljubodrag (2011). "Yugoslav-Soviet Relations: The View of the Western Diplomats (1944-1946)". The Balkans in the Cold War: Balkan Federations, Cominform, Yugoslav-Soviet Conflict. Belgrade, Serbia: Institute for Balkan Studies. pp. 109–140. ISBN 9788671790734.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Karchmar, Lucien (1982). "The Tito-Stalin Split in Soviet and Yugoslav Historiography". In Vucinich, Wayne S. (ed.). At the Brink of War and Peace: The Tito-Stalin Split in a Historic Perspective. New York, New York: Brooklyn College Press. pp. 253–271. ISBN 9780914710981.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laković, Ivan; Tasić, Dmitar (2016). The Tito–Stalin Split and Yugoslavia's Military Opening toward the West, 1950–1954: In NATO's Backyard. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 9781498539340.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mehta, Coleman (2011). "The CIA Confronts the Tito-Stalin Split, 1948–1951". Journal of Cold War Studies. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 13 (1): 101–145. doi:10.1162/JCWS_a_00070. ISSN 1520-3972. JSTOR 26923606. S2CID 57560689.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stokes, Gale, ed. (1996). "The Expulsion of Yugoslavia". From Stalinism to Pluralism: A Documentary History of Eastern Europe Since 1945 (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195094466.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- West, Richard (1994). "The Quarrel with Stalin". Tito: And the Rise and Fall of Yugoslavia. London, UK: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-28110-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

![]() Works related to Resolution of the Information Bureau Concerning the Communist Party of Yugoslavia at Wikisource

Works related to Resolution of the Information Bureau Concerning the Communist Party of Yugoslavia at Wikisource