Leonid Krasin

Leonid Borisovich Krasin (Russian: Леони́д Бори́сович Кра́син; 15 July 1870 – 24 November 1926) was a Russian Soviet politician, engineer, social entrepreneur, Bolshevik revolutionary politician and a Soviet diplomat.

Leonid Krasin | |

|---|---|

| |

| People's Commissar for Foreign Trade | |

| In office 6 July 1923 – 18 November 1925 | |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Tsiurupa |

| People's Commissar for Trade and Industry | |

| In office November 1918 – June 1920 | |

| People's Commissar for Transport | |

| In office March 1919 – December 1920 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Leonid Borisovič Krasin 15 July 1870 Kurgan, Tobolsk Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 24 November 1926 (aged 56) London, United Kingdom |

| Citizenship | Soviet |

| Political party | RSDLP (1898–1903) RSDLP (Bolsheviks) (1903–1918) Russian Communist Party (1918–1926) |

| Alma mater | Kharkov Technological Institute |

Early years

Krasin was born in Kurgan, Tobolsk Governorate in Siberia. His father, Boris Ivanovich Krasin, was the local chief of police. The young Leonid was a star pupil at school, and met the American explorer George Kennan when he visited Siberia.[1] Krasin joined the Social Democratic Labor Party during the 1890s. Arrested towards the end of the 1890s, he was sent to internal exile in Siberia where he worked as a draughtsman on the Trans-Siberian Railway. He graduated from Kharkov Technological Institute in 1901.

Career

In 1903 the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) split into Menshevik and Bolshevik factions; Krasin supported the latter, and was elected to the Bolshevik Central Committee the same year.

On his release from exile in 1900 he had moved to Baku on the Caspian Sea, where "Koba" Jughashvili (later known as Joseph Stalin) was also active at the time. In Baku, Krasin used his financial contacts to help establish an illegal printing-press; this Nina Printing House became for a period the main vehicle for Vladimir Lenin's newspaper Iskra. Krasin left Baku in 1904 to work as the chief engineer of Savva Morozov.

His activities during the 1905 Revolution primarily involved sourcing finance for the Bolshevik revolutionaries, including organizing bank robberies. Krasin helped plan the 1907 Tiflis bank robbery, a bloody crime that took place in the middle of Yerevan Square, killing forty and injuring 50.

Krasin enjoyed the excitement of terrorism. His home was the main laboratory in which were manufactured the bombs used to attack Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin (in office: 1906-1911).[2]

The quest for excitement caused a break with Lenin. Lenin, who was usually acerbic in such circumstances, remained complimentary towards Krasin, and continued to exhort him to rejoin the Party.[3]

In 1908 Krasin left Russia and in 1909 collaborated with Alexander Bogdanov in the launch of the Vpered faction of the RSDLP. Later he withdrew from political activities for many years. He had a successful career as an electrical engineer, working for Siemens in Germany and in Russia and becoming a millionaire. After the February Revolution of 1917 he returned to the fold and rejoined the Bolsheviks.[4] In the Russian Bolshevik government Krasin served as People's Commissar of Foreign Trade from 1920 to 1924.

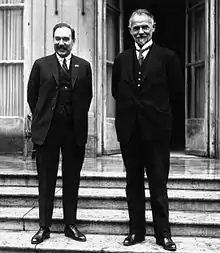

Diplomatic career

Krasin met E. F. Wise in Copenhagen in April 1920. Wise was representing the Entente's Supreme Economic Council; with him Krasin negotiated the Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement, signed in March 1921. In 1924 Krasin was elected to the Communist Party's Central Committee, an office he held until his death in 1926.

In 1924 he became the first Soviet Ambassador to France. He left a year later to become the Soviet Plenipotentiary in London, where he died. His role in London was filled by Christian Rakovsky after his death.

Role in project of Lenin's tomb

Krasin, in the tradition of Nikolai Federov, believed in immortalization by scientific means. At the funeral of Lev Karpov in 1921, he said:

I am certain that the time will come when science will become all-powerful, that it will be able to recreate a deceased organism. I am certain that the time will come when one will be able to use the elements of a person's life to recreate the physical person. And I am certain that when that time will come, when the liberation of mankind, using all the might of science and technology, the strength and capacity of which we cannot now imagine, will be able to resurrect great historical figures- and I am certain that when that time will come, among the great figures will be our comrade, Lev Iakovlevich.[5]

Lenin died in January 1924. Shortly afterwards Krasin wrote an article on "The Immortalization of Lenin" and proposed a monument containing Lenin's corpse that would become a center of pilgrimage like Jerusalem or Mecca. Krasin, along with Anatoly Lunacharsky, announced a contest for designs of the permanent monument/mausoleum. Krasin also attempted - unsuccessfully - to preserve Lenin's body cryogenically.[6]

Personal life

With his wife, they were the parents of three daughters, including:[7]

- Liubov Krasin, who married French politician and diplomat Gaston Bergery, founder of the Frontist Party, from whom she was divorced in 1928. After the war she married French politician and journalist Emmanuel d'Astier de La Vigerie.[8]

- Ludmilla Krasin, who was reportedly engaged to the Duc de La Rochefoucauld in 1927.[9] She married John Mathiessen Mathias (1906-1963), a son of Robert Moritz Mathias.[10]

While Krasin was negotiating formal recognition of the Bolshevik government by the United Kingdom and France, and despite remedies proposed by his old friend, the physician Alexander Bogdanov, he died from a blood disease. Krasin's funeral procession three days later included 6,000 mourners, many of them Bolshevik sympathizers; he was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium before being buried at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Moscow.

Honors and legacy

During the Great Purge and until Stalin's death in 1953, he was largely omitted from the history of the Communist Party and the Soviet government.[11]

Two icebreakers (one launched in 1917 and one in 1976) commemorated Krasin.

Texts

- "Our Trade Policy", Labour Monthly, Vol II, No.1, January 1922

- Archive of Leonid Borisovič Krasin Papers at the International Institute of Social History

Notes

- Glenny, Michael (Oct 1970). "Leonid Krasin: The Years before 1917. An Outline". Soviet Studies. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. 22 (2): 192–221. doi:10.1080/09668137008410749. JSTOR 150054.

- Felshtinsky, Yuri (2003). Preface to Leonid Krasin: Letters to His Wife and Children (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2011-07-11.

- Adam Ulam Stalin: The Man and His Times

- 'The Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement, March 1921', M. V. Glenny, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 5, No. 2. (1970), pp. 63-82.

- Tumarkin, Nina (1981). "Religion, Bolshevism, and the Origins of the Lenin Cult". Russian Review. 40 (1): 35–46. doi:10.2307/128733. JSTOR 128733.

- John Gray, The Immortalization Commission, 2011, pp. 161-166.

- "Leonid Borisovich Krasin , Soviet Bolshevik politician, and his wife..." www.gettyimages.co.uk. Getty Images. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- "Gen. d'Astier de la Vigerie Dies; Air Officer Was de Gaulle Aide". The New York Times. 11 October 1956. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- "LUDMILLA KRASSIN TO WED FRENCH DUKE; Daughter of Late Leonid Krassin, Soviet Envoy to England, to Wed De Rochefoucauld". The New York Times. 5 August 1927. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- Pound, Ezra (2015). Ezra Pound and 'Globe' Magazine: The Complete Correspondence. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-4725-8961-3. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- Roy Medvedev, Let History Judge, 1971

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leonid Krasin. |