Leopold Trepper

Leopold Zakharovitch Trepper (23 February 1904 – 10 January 1982) was a Polish Communist and career Soviet agent of the Red Army Intelligence. With the code name Otto, Trepper had worked with the Red Army since 1930.[1][2] He was also a resistance fighter and journalist.[3]

Le Grand Chef Leopold Trepper | |

|---|---|

Leopold Trepper in later life | |

| Born | 23 February 1904 |

| Died | 19 January 1982 (aged 77) |

| Nationality | Polish, Israeli |

| Occupation | Active Resistance leader, agent of GRU |

| Years active | 1923-1982 |

| Organization | Hashomer Hatzair (1924-1929) Red Orchestra |

| Known for | Head of a Resistance group |

Trepper and Richard Sorge, a Soviet military intelligence officer, were the two main Soviet agents in Europe and were employed as roving agents to set up espionage networks throughout Europe and in Japan. While Sorge was a penetration agent, Trepper ran a series of clandestine cells for organising agents in Europe. Trepper used the latest technology at the time—small wireless radios—to communicate with Soviet intelligence. Although the Funkabwehr's monitoring of the radios transmission eventually led to the organisation's destruction, this sophisticated use of the technology enabled the espionage organisation to behave as a network with the ability to achieve tactical surprise and deliver high-quality intelligence, such as the warning of Operation Barbarossa.[4]

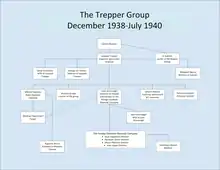

In 1936, Trepper became the technical director of a Soviet Red Army Intelligence unit in western Europe.[5] He was responsible for recruiting agents and creating espionage networks.[5] Trepper was an experienced intelligence officer, and an extremely resourceful and capable man completely at home in the west. He was a man who could not be drawn in conversation, who lived a reclusive life, and had a talent of judging people that enabled him to easily penetrate significant groups.[6] By the start of World War II, Trepper controlled a large espionage network in Belgium and seven separate espionage networks in France.[7] His operation was known as the Red Orchestra to the Abwehr.

Life

On 23 February 1904, Leopold Trepper was born to a large Jewish family of 10 children in Nowy Targ, Poland, which was part of Austria-Hungary at the time.[8] Trepper's father was a travelling farm machinery and seed merchant who died when Trepper was almost twelve.[8] His parents sent him to school in Lviv, Ukraine, to escape the strong militant and anti-Semitic tradition in Poland.[8] Trepper met Sarah Orschitzer in Lviv, who worked in a chocolate factory and took evening classes to train as a teacher.[9] She was either Trepper's mistress or wife,[5] and also a Jewish communist who travelled under the alias Luba Brekson.[9] After school, Trepper moved to Kraków to study history and literature at the Jagiellonian University.[8] His lack of money led him to left-wing student groups.[10] After the October Revolution, he joined the Bolsheviks and became a communist.

After the war with the Soviet Union, Poland suffered an economic crisis and Trepper had to leave university due to a lack of funds.[8] He found work first as a workshop locksmith, mason, and later worked in the mines in Katowice.[7] Due to extreme poverty and lack of food, he agitated the workers to strike.[8] As one of the ringleaders, he was caught and imprisoned for eight months.[10]

Trepper applied for a visa to France when he found it impossible to obtain work after the uprising, but was refused. In 1916, his father died leaving the family in financial straits.[11] In the same year, Trepper joined the Zionist, socialist movement Hashomer Hatzair. In April 1924 its members helped him to emigrate to Haifa, Palestine,[3] via Brindisi to work on the roads. Later in a kibbutz,[12] Orschitzer followed Trepper to Palestine. She was involved in an illegal communist demonstration, and was arrested and jailed; she would have been deported had she not married a Palestinian citizen.[13]

After moving to Tel Aviv in 1929, Trepper became a member of the central committee of the Palestine Communist Party.[12] Between 1928 and 1930, Trepper was the organiser of the Eḥud or Unity faction, a Jewish-Arab communist labour organisation within the Histadrut trade union body;[14] most of its members came from the Kerem HaTeimanim area and worked against the British forces in Palestine. In 1929, he attended a meeting of the International Red Aid,[10] where he was identified as an agitator and militant communist by the British, who subsequently arrested and interned him for 15 days at the citadel's prison in Acre, Israel.[10] Trepper organised a hunger strike after learning that the communist prisoners were to be deported.[15] He was released after news of the hunger strike reached London and the British newspapers, and he and the hunger strikers were placed on stretchers outside the prison, as they were too weak to walk due to lack of food.[15]

In March 1930, after he was given the choice of leaving Palestine or being forcefully deported to Cyprus, Trepper travelled via Syria to Marseille, France, and worked as a dishwasher.[16] He then travelled to Paris where he found work as a decorator living a poor existence.[10] He came into contact with numerous left wing intellectuals and communist workers that eventually led him to become a member of the Rabkor,[10] an illegal political organisation that was dominated by communists who sent both men and intelligence to Moscow.[17][18] He continued to work for the organisation until French intelligence dismantled it in 1932.[17] Trepper left Paris on a Polish passport and escaped to Berlin by train,[10] where he contacted the Soviet embassy.[19] After several days, he was ordered to report to Moscow in the spring of 1932.[20][21]

Between 1932 and 1935, Trepper worked to become a GRU agent by learning his trade. After attending KUNMZ University, where he obtained a diploma, he studied history at the Institute of Red Professors and was awarded a degree, allowing him to work as a history teacher in Moscow. Trepper was in constant touch with the Russian intelligence instructors who taught him the practical skills of an espionage agent. At the same time, Orschitzer also attended KUNMZ University for a year.[10] In 1935, Trepper submitted a newspaper column covering art to the newspaper for Russian Jews called Truth.[22] In the winter of the same year his training was completed.[10]

Espionage career

In 1935 or 1936, Trepper was given the post of technical director of Soviet intelligence in Western Europe and was known as the Big Chief.[5] He returned to Paris, France,[5] on a passport under the name Sommer, and spent five months investigating the extensive network and accidentally exposed a double agent: a Dutch Jew who was the former head of the Soviet espionage network in the United States and was turned by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.[22] He returned to the Soviet Union under the name Majeris to inform Soviet intelligence of his findings and went back to Paris five months later.[22] In 1936 Trepper visited Scandinavia for a short-term technical mission, before returning to Paris—which remained his base until the end of 1938—in December. For most of 1937, Trepper was concerned with extensive planning and re-organisation of Soviet intelligence operations in Western Europe; in that year he visited Switzerland, the British Isles, and Scandinavia.[5]

Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company

In the autumn of 1938, Trepper made contact with the Jewish businessman Léon Grossvogel, whom he knew in Palestine.[23] Grossvogel ran a small business called Le Roi du Caoutchouc or The Raincoat King on behalf of its owners. Trepper used provided money to create the export division of The Raincoat King called the Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company,[23] which dealt in raincoat exports and was considered by Trepper to be the ideal cover for the group's espionage network.[24] As the business had to operate with the full knowledge of the state, shares had to be issued. Among the shareholders was former official of the Belgian Foreign Office,[25] Jules Jaspar.[26] Jaspar's brother, Henri Jaspar, was the former prime minister of Belgium, so Jaspar was seen as the ideal person to direct the company and provide it with a veneer of respectability.[25] The company was created in December 1938.[27]

On 6 March 1939, Trepper used the alias Adam Mikler and identified as a wealthy Canadian businessman, traveled from Quebec while being accompanied by Orschitzer, who traveled as Anna Mikler. They moved to Brussels from Paris, making it their new base and settled in their apartment located at 198 Avenue Richard Neybergh, Brussels.[27][28] After the company was created, Trepper used the circulation of gossip and rumours by his group to spread the word that a wealthy Canadian had funded the business to establish his cover in the Belgian business community.[27] On 25 March 1939, Trepper met the GRU intelligence agent Mikhail Makarov in a café.[29] Makarov, a wireless telegraphy (WT) operator, forger, and expert on secret inks,[30] had been sent from Moscow via Stockholm and Copenhagen to Paris whilst travelling on a Uruguayan passport, under the alias Carlos Alamo.[31] Makarov's original duty was to provide Trepper with forged documentation, but since Grossvogel had introduced Abraham Rajchmann, who became the group's forger, he became a WT operator for the group instead and was posted to Ostend to work at a branch of the Raincoat Company, which was sold to him to strengthen his cover. Makarov immediately started to train other operators in WT procedure.[30] In July 1939 Anatoly Gurevich, posing as the wealthy Vincente Sierra, arrived in Brussels on a Uruguayan passport,[32] and contacted Trepper in Ghent on 17 July.[33] It was arranged that Trepper would teach the operation of the Raincoat Company to Gurevich, who would then move to Denmark to establish a new firm.[34] To make contacts across different social strata, Gurevich familiarised himself with Belgian society and studied the country to learn about its economy. Gurevich took part in ballroom dancing and riding lessons, and as he travelled between luxury hotels, mail bearing the stamps of Uruguay awaited his arrival.[33] In the months leading up to the war, Trepper's plans changed, and Gurevich ended up working as an assistant to Trepper. Gurevich performed the normal bureaucratic operations in an espionage network including being a cipher clerk, deciphering instructions from Soviet intelligence, and preparing reports with information forwarded from a contact in the Soviet Trade Representation of Belgium.[33] In 1939, Trepper met the American classical dancer, Georgie De Winter in Brussels.[23] De Winter became Trepper's mistress and had a child, Patrick De Winter; historians are unsure if the child was Trepper's.[30]

France

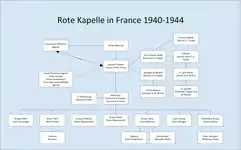

In July 1940, Trepper fled Belgium with Grossvogel and moved to Paris, where Grossvogel and Polish Jew Hillel Katz were Trepper's main assistants.[35] Trepper changed his alias to Jean Gilbert and got in touch with General Ivan Susloparov, who was the Soviet military attaché in the Vichy government.[36][37] On their first meeting, Trepper informed Susloparov of Adolf Hitler's plan to invade the Soviet Union, which the latter believed to be true.[38] Trepper also arranged to have his wife and child returned to Moscow,[39] and they left in August 1940. However, his main goal was to find and make use of a radio transmitter and a radio operator. Susloparov supplied the names of a couple who were Polish militant communists—Hersch and Miriam Sokol—as possible radio operators—but both the Sokols had to be trained in radio procedures by Grossvogel.[40] At the same time, Trepper recruited civil engineer and Russian aristocrat Basil Maximovitch.[41]

Simexco and Simex

In March 1941, Simexco was established in Paris as a replacement cover company. The firm's profits were channelled to provide funding to the group, via its Department III. The firm made a considerable profit over the year that was used by both Trepper and Gurevich as a personal expense account. Additional funding came from Soviet intelligence, and was received in monthly sums of $8,000 to $10,000 through the Russian military attaché in Paris. When the war started, the funds were sent via Switzerland in dollar amounts that were agreed in advance with Soviet intelligence via radio and delivered to Trepper. The money was used to maintain the operations of the Trepper group and to cover the necessary expenses to carry out special assignments. Trepper spent lavishly on bribes, the upkeep of the Château de Billeron, sundries, and large daily expenses to maintain his cover as a successful businessman.[42]

Robinson network

In September 1941, Trepper met with Comintern agent Henry Robinson, who was one of the most important sources of intelligence in Paris. He ran his own large espionage network, which had revealed to the Soviets that Hitler was inclined to call off Operation Sea Lion, the plan to invade the British Isles.[43] The Cominterm organisation had lost prestige with Stalin, who suspected it of deviating from Communist norms. Robinson was also suspected of being an agent of the Deuxième Bureau and was subsequently in ideological conflict with Soviet intelligence.[44] It was unusual for two senior agents to meet, but an exception was made as it was felt by Soviet intelligence that Robinson's extensive contacts could help Trepper build his French network.[45] Trepper learned of a radio transmitter that was being run by the French Communist Party in Paris from Robinson, and was ordered to take charge of Robinson's network.[46]

Around that time, Trepper was introduced to Anna Maximovitch by her brother Basil Maximovitch. Both Anna and Basil became very important to Trepper:[41] Basil had an affair with Margarete Hoffman-Scholz, secretary to Wehrmacht colonel Hans Kuprian, who was on a committee that processed prisoners from the Vichy government for slave labour, and a niece to General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel, military commander of Paris;[47] Anna was a psychiatric neurologist who opened a clinic in Choisy-le-Roi in the late 1940s. It was a moneyed area of Paris which enabled her to pick up gossip and recruit from her patients, some of whom were high ranking French nobility and administrative people including Rohan-Chabot's husband, Alain Louis Auguste Marie de Rohan-Chabot, who was a French officer and resistance fighter.. One of those patients was Helene Claire Marie de Liencourt, Countess de Rohan-Chabot, who rented out the empty 18th-century Château Billeron located in Lugny-Champagne to Maximovitch as a meeting place for the group.[48][49]

Rue des Atrébates

On 30 November 1941, the house at 101 Rue des Atrébates in Brussels, run by Rita Block and Zofia Poznańska and used to transmit intelligence, was discovered by the Funkabwehr.[50] On 12 December 1941, the residence was raided by the Abwehr.[50]

By February 1942, Trepper re-established communication with Soviet intelligence and was able to give a full report on the situation.[51] The Soviets instructed Trepper to contact Soviet Army Captain Konstantin Jeffremov, who had been living in Belgium.[52] In May 1942, a meeting was arranged between the two men in Brussels, where Trepper instructed Jeffremov to take over Gurevich's Belgian and low-countries espionage network.[51] He also instructed him to maintain radio silence for six months, and gave Jeffremov 100,000 Belgian francs for expenses.[51] Radio communications for the espionage group in Brussels was to be operated by GRU agent Johann Wenzel. In January 1942, Trepper ordered Gurevich to travel to Marseilles with Jules Jaspar and Alfred Corbin to establish a new branch office of Simex to enable the recruitment of a new espionage network.[53][54]

In May 1942, Wenzel began transmitting important traffic to the Soviet Union.[55] On 29–30 June 1942, the house that Wenzel was transmitting from, 12 Rue de Namur in Brussels, was raided by the local police under the command of Abwehr officer Harry Piepe.[56] Wenzel was interrogated and tortured by the Gestapo for six to eight weeks and confessed to everything, including the cypher keys he used and his code name,[57] which allowed the Funkabwehr to decipher a large amount of back traffic belonging to the group.[2] After Wenzel's arrest, Jeffremov tried to hide, but was arrested on 22 July 1942 while trying to obtain false identity papers.[58] One of the names that Wenzel surrendered was Rajchmann, who was placed under surveillance and arrested on 2 September 1942. Almost immediately, Rajchmann agreed to cooperate with the Abwehr.[59] On 12 October 1942, Malvina Gruber, Rajchmann's mistress was arrested by the Abwehr in Brussels,[60] and she immediately decided to cooperate with the Abwehr. She spoke of Gurevich and exposed the Trepper espionage network in France.[61] Jeffremov (sources vary) also exposed the Simexco company name and the Trepper espionage network in France to the Abwehr.[62]

Reorganisation

When the Sokols and Johann Wenzel were arrested, Trepper lost his radio link with Soviet intelligence. Trepper asked Robinson to arrange a radio link to Soviet intelligence, but the latter refused.[46] Trepper turned to Gurevich in Marseille and visited him several times to establish contact with the Soviets, but Gurevich refused to use his transmitter and was effectively lost to the network.[63] Trepper was forced to turn to Pierre and Suzanne Giraud,[64][lower-alpha 1] who were established to have a transmitter either at Saint-Leu-la-Forêt or Le Pecq (sources vary)[64][65] by Grossvogel and ordered to master the equipment. Suzanne had originally worked as a cutout for Trepper, and the couple were unprepared for the work;[66] they failed and were arrested by the Gestapo.[64]

Arrest

On 19 November 1942, the premises of Simexco were searched by the Abwehr, and all known associates of the company were arrested. However, no espionage material was found and the interrogation of prisoners failed to determine the whereabouts of Monsieur Gilbert, the alias that Trepper was using in his dealings with the firm.[67] After being tortured, the French commercial director of the firm Alfred Corbin informed the Gestapo of the address of Trepper's dentist,[68] where Trepper was arrested on 25 November 1942 by Karl Giering.[69] Trepper was imprisoned on a third floor room at Rue des Sausasaies in Paris.[70] He offered to collaborate with the Abwehr, who subsequently treated Trepper leniently in the expectation that he would serve as a double agent in Paris.[68] He was allowed to take daily walks and go into town to buy necessities, but always accompanied by two Sonderkommando guards.[70] According to Piepe, when Trepper talked, it was not out of fear of torture or death, unlike Wenzel, but out of duty.[71] While he gave up the names and addresses of most of the members of his own network,[70] he sacrificed his associates to protect the various members of the French Communist Party, whom he had an absolute belief in.[71] The first people to be betrayed were his assistants Katz and Grossvogel.[72] In 2002, author Patrick Marnham suggested Trepper not only exposed the Soviet agent Henri Robinson, but may have been the source that betrayed French resistance leader Jean Moulin.[73] When Gurevich was arrested on 9 November 1942 in Marseille, he was moved to Paris and kept in the next room to Trepper. There was a mutual animosity between the two men.[70]

Funkspiel

On 25 December 1942, Trepper was informed that he would be running a Funkspiel operation with Gurevich.[74] On 13 February, Trepper was moved to a house belonging to Karl Bömelburg at 40 boulevard Victor Hugo, Neuilly-sur-Seine.[75] Over the next month, the Gestapo conducted a battle of wits with Trepper and Gurevich in the hope of exposing more members of the espionage network.[76]

Escape

On 13 September 1943, Trepper escaped Gestapo custody under watch while visiting a pharmacy, Pharmacie Baillie, near the railway station at St. Lazare and avoided recapture.[77] He contacted Georgie De Winter, and they both agreed to hide out in Le Vésinet,[78] where he wrote to Heinz Pannwitz to explain his disappearance was not an escape, but merely an attempt to ensure he stayed alive as a move that designed to provide the maximum advantage for Soviet intelligence.[78] On 18 September 1943, the couple moved to a house in Suresnes that belonged to Mrs. Queyrie; De Winter worked as a courier to arrange the move.[78] Trepper wrote to Pannwitz a second time, deploring the fact that in spite of his request, a search was being made for him, and that he was placed in a very uncomfortable position.[79] At the time, Trepper was the subject of an Identification Order in France, German and Belgium as a "wanted dangerous spy".[71]

Trepper contacted Suzanne Spaak and Jean Claude Spaak through De Winter, using the alias Jean Gilbert, in the hope that he could send a message to the Soviet military attaché in London and make contact with the French Communist Party who could also possibly send a message.[80][78] Jean Claude Spaak was a brother to Belgian prime minister Paul-Henri Spaak.[81] Suzanne had a wide range of contacts and it was through her influence that Trepper hoped to contact Moscow.[78] While they were waiting, De Winter organised another location where they could hide on Rue Du Chabanais, and they moved in on the 24 September.[78] Jean Claude had not heard from Trepper since 1942, when the Sokols had left a large sum of money, their identity, and ration cards with Spaak for safekeeping.[80] Trepper asked Jean Claude to send a message: "I will be at the church every Sunday morning between 10 and 11am. Signed Martik."[80] Trepper hoped to make contact with an agent at a church in Auteuil.[82] Trepper sent De Winter several Sundays in a row, but no contact was made.[78] The couple then moved to a guest-house at Bourg-la-Reine. Trepper, who wanted to restart his clandestine activities, was wary of De Winter being identified by the Gestapo due to her constant visits to the Spaak household. He asked Jean Claude for 100,000 francs,[78] which he gave to De Winter for expenses and sent her to a hideout in a village near Chartres in the hope that she could be smuggled into the non-occupied zone.[78] De Winter was provided with a letter of introduction by Antonia Lyon-Smith, a friend of the Spaaks, to a local doctor in Saint-Pierre-de-Chartreuse.[78][83] En route, De Winter was arrested on 17 October 1943 by Pannwitz. At the same time, Trepper went to the church in Auteuil and noticed a black Citroën car—the signature car of the Gestapo—and fled.[77] Trepper learned that the Gestapo had visited all his previous addresses and were close to capturing him. He warned Jean Claude, who sent both his wife and children to Belgium, before travelling to Paris, where he hid out with friends until the end of the war. Trepper last saw Jean Claude before the liberation of 23 October 1943.[80]

Postwar period

The Soviets arrested Trepper in 1945 and took him to Russia;[3] since 1938, he had been under suspicion, as he was recruited by General Yan Karlovich Berzin,[84] who had fallen out of favour and was dismissed in 1935.[84] Trepper was personally interrogated by SMERSH Chief Viktor Abakumov, and was interned in Lubyanka,[85] Lefortovo, and Butyrka prison.[84] He vigorously defended his position and managed to avoid execution, but remained in prison until 1955 for unknown reasons. After his release, he submitted a detailed plan to revive both Jewish cultural life and institutions in the Soviet Union, but the plan was rejected in 1956 after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union meeting.[3] Afterwards, he returned to Warsaw to his wife and three sons. Trepper was elected to run the Yidisher Kultur-Gezelshaftlekher Farband and also ran its Jewish publishing house, Yiddish Bukh.[3]

Emigration to Israel

After the Six-Day War in June 1967 and the subsequent antisemitic campaign that developed in Poland in 1968, Trepper planned to emigrate to Israel.[3] However, while the Polish communist government promoted and encouraged the emigration of thousands of Jews at that time, Trepper was continually refused a visa.[3] Permission was refused until international pressure from worldwide publicity that the campaign was receiving, including his sons' protests and hunger strikes, forced the authorities to allow him and a few Jewish people who were in a similar situation to leave. He settled in Jerusalem in 1974.[3]

Death

Trepper died in Jerusalem in 1982 and was buried there.[3] According to a contemporary report from the news agency, Jewish Telegraphic Agency, "no government representatives or officials attended his funeral", though the Israeli Defence Minister Ariel Sharon, later the 11th Prime Minister of Israel, subsequently awarded Trepper the Emblem of Israel in a ceremony "attended by dozens of former members of anti-Nazi partisans and fighting groups".[86]

Bibliography

- Trepper, Leopold; Rotman, Patrick (1975). Le grand jeu. Paris: A. Michel. ISBN 9782226001764.

- Gurevich, Anatoly (1995). Un certain monsieur Kent (in French). Paris: B. Grasset. ISBN 2246463319.

In 1975, he published his autobiography, The Great Game. A few years before, a book about the Red Orchestra containing interviews with both Soviets and Nazis had appeared, written by Gilles Perrault.

Notes

- Suzanne Giraud was also known as Lucienne Giraud.

References

- Coppi Jr., Hans (July 1996). Dietrich Bracher, Karl; Schwarz, Hans-Peter; Möller, Horst (eds.). "Die Rote Kapelle" [The Red Orchestra in the field of conflict and intelligence activity, The Trepper Report June 1943] (PDF). Quarterly Books for Contemporary History (in German). Munich: Institute of Contemporary History. 44 (3). ISSN 0042-5702. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "Trepper, Leopold". Jewish Virtual Library. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- Sims, Jennifer (2005). "Transforming U.S. Espionage: A Contrarian's Approach". Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. Georgetown University Press. 6 (1): 53–59.

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. p. 14. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 15. ISBN 0805209522.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. p. 52. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Green, David B. (22 February 2014). "This Day in Jewish History / Soviet Spy Leopold Trepper Is Born" (Audio). Haaretz Daily Newspaper Ltd. Haaretz. Jewish World. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 16. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 22. ISBN 0805209522.

- Green, David B. (27 October 2019). "This Day in Jewish History / Soviet Spy Leopold Trepper Is Born". Haaretz Daily Newspaper. Haaretz. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 17. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 17. ISBN 0805209522.

- Bennett, Richard (24 April 2012). Espionage: Spies and Secrets. Ebury Publishing. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-4481-3214-0. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 19. ISBN 0805209522.

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. p. 21. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 21. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 23. ISBN 0805209522.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 29. ISBN 0805209522.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2.

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. p. 23. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 42. ISBN 0805209522.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945. Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 21. ISBN 0-89093-203-4.

- "Правда о "Красной капелле"". Week 3622: Редакция «Российской газеты. Российской газеты. 5 November 2004. Retrieved 8 April 2019.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. p. 72. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "The case of the Rote Kapelle. These three volumes are the Final Report". The National Archives. KV 3/349. 17 October 1947. p. 9. Retrieved 26 December 2019.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Erofeev, Yuri Nikolaevich (24 November 2006). "The general who went down in history" (in Russian). Moscow. Nezavisimaya Gazeta. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Jeffery T. Richelson (17 July 1997). A Century of Spies: Intelligence in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-19-511390-7. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Nigel West (12 November 2007). Historical Dictionary of World War II Intelligence. Scarecrow Press. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-8108-6421-4. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 104–106. ISBN 0805209522.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. p. 25. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Uri Bar-Joseph; Rose McDermott (2017). Intelligence Success and Failure: The Human Factor. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-19-934174-0. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 188. ISBN 0805209522.

- "The case of the Rote Kapelle". The National Archives. KV 3/349. 17 October 1947. p. 9. Retrieved 24 December 2019.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Stephen Tyas (25 June 2017). SS-Major Horst Kopkow: From the Gestapo to British Intelligence. Fonthill Media. p. 91. GGKEY:JT39J4WQW30.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 177–179. ISBN 0805209522.

- Guillaume Bourgeois (24 September 2015). La véritable histoire de l'orchestre rouge. Nouveau Monde Editions. p. 228. ISBN 978-2-36942-069-9. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 181–184. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 83. ISBN 0805209522.

- "The case of the Rote Kapelle". The National Archives. KV 3/349. 17 October 1947. p. 6. Retrieved 24 December 2019.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 100–102. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 100. ISBN 0805209522.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945. Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 77. ISBN 0-89093-203-4.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945. Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 384. ISBN 0-89093-203-4.

- Stephen Tyas (25 June 2017). SS-Major Horst Kopkow: From the Gestapo to British Intelligence. Fonthill Media. pp. 91–92. GGKEY:JT39J4WQW30. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Stephen Tyas (25 June 2017). SS-Major Horst Kopkow: From the Gestapo to British Intelligence. Fonthill Media. p. 384. GGKEY:JT39J4WQW30. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 338. ISBN 0805209522.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. p. 58. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 158. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 194. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 194. ISBN 0805209522.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. p. 58. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 254–258. ISBN 0805209522.

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. p. 4. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 264–268. ISBN 0805209522.

- Marnham, Patrick (2002). Resistance and betrayal : the death and life of the greatest hero of the French Resistance (1st U.S. ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0375506086. OCLC 224063740.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 268. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 317. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 348–365. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 365. ISBN 0805209522.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 367–377. ISBN 0805209522.

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. p. 8. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. pp. 122–125. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Bauer, Arthur O. "KV 2/2074 - SF 422/General/3". The National Archives, Kew. p. 18. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Perrault, Gilles (1969). The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books. p. 382. ISBN 0805209522.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. pp. 122–124. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Tucker, Robert C. (March 1978). "Stalinism: Essays in Historical Interpretation". Slavic Review. Cambridge University Press. 37 (1): 128–130.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936-1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Posthumous Award for Trepper". Jewish Telegraph Agency. Archive: Archive of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 23 February 1982. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

Bibliography

- Coppi, Hans (1996), Die "Rote Kapelle" im Spannungsfeld von Widerstand und nachrichtendienstlicher Tätigkeit. Der Trepper-Report vom Juni 1943, Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 3/1996, 431-548

- Hastings, Max (2015). The Secret War: Spies, Codes and Guerrillas 1939 -1945. London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-750374-2.