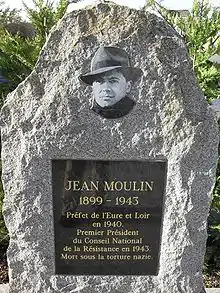

Jean Moulin

Jean Pierre Moulin (French: [ʒɑ̃ mu.lɛ̃]; 20 June 1899 – 8 July 1943) was a French civil servant who served as the first President of the National Council of the Resistance during World War II from 23 May 1943 until his death less than two months later.[1][2]

Jean Moulin | |

|---|---|

Moulin in 1937 | |

| Born | 20 June 1899 |

| Died | 8 July 1943 (aged 44) Near Metz, Occupied France |

| Resting place | Panthéon, Paris |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Prefect |

| Known for | First President of the National Council of the Resistance |

| Parent(s) | Antoine-Émile Moulin Blanche Élisabeth Pègue |

A prefect in Aveyron (1937–1939) and Eure-et-Loir (1939–1940), he is remembered today as one of the main heroes of the French Resistance, unifying it under Charles de Gaulle. He was tortured by German officer Klaus Barbie while in Gestapo custody; he died in the train that transported him to Germany before crossing the border. His death was registered at Metz railway station.[2][3]

Early life

Jean Moulin was born at 6 Rue d'Alsace in Béziers, Hérault, son of Antoine-Émile Moulin and Blanche Élisabeth Pègue. He was the grandson of an insurgent of 1851. The father of Jean Moulin was a lay teacher at the Université Populaire and a Freemason at the lodge Action Sociale. Jean Pierre Moulin was baptised on 6 August 1899[4] in the church of Saint-Vincentin in Saint-Andiol (Bouches-du-Rhône), the village his parents came from. He spent an uneventful childhood in the company of his sister, Laure, and his brother Joseph. Joseph died of pneumonia in 1907. At Lycée Henri IV in Béziers, Jean was an average student.[5]

In 1917, he enrolled at the Faculty of Law of Montpellier, where he was not a brilliant student. However, thanks to the influence of his father, he was appointed as attaché to the cabinet of the prefect of Hérault under the presidency of Raymond Poincaré.

Military service

Mobilised on 17 April 1918, Moulin was assigned to the 2nd Engineer Regiment, based in Metz after the victory. After an accelerated training, he arrived in the Vosges at Charmes on 20 September and was preparing to go to the front lines when the armistice was proclaimed. He was posted successively to Seine-et-Oise, Verdun and Chalon-sur-Saône. He worked as a carpenter, a digger and later a telephonist for the 7th and 9th Engineer Regiments. He was then demobilized and resumed his duties at the prefecture of Montpellier on 4 November 1919.

Interwar years

After World War I, Moulin resumed his studies and obtained a law degree in 1921. He then entered the prefectural administration as chief of staff to the deputy of Savoie in 1922 and then sous-préfet of Albertville from 1925 to 1930.

After being rejected by Jeanette Auran, Moulin, aged 27, married a 19-year-old professional singer, Marguerite Cerruti, in the town of Betton-Bettonet in September 1926. Cerruti quickly became bored with the marriage, and Moulin responded by offering her further singing lessons in Paris, where she disappeared for two days.[6] Biographer Patrick Marnham cites one of the causes of the divorce being Moulin's mother-in-law, who had wanted to prevent her estate passing into Moulin's control upon Cerruti's 21st birthday. Moulin attempted to hide his rejection by the bourgeoisie by excusing his wife's disappearances and not informing his family until after his divorce.[7]

Moulin was appointed sous-préfet of Châteaulin, Brittany in 1930, but he also drew political cartoons for the newspaper Le Rire under the pseudonym Romanin. He also illustrated books by the Breton poet Tristan Corbière, including an etching for La Pastorale de Conlie, Corbière's poem about Camp Conlie where many Boon soldiers died in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War. He also made friends with the Breton poets Saint-Pol-Roux in Camaret and Max Jacob in Quimper.[8]

In 1932, Pierre Cot, a Radical Socialist politician, named Moulin his second in command or chef adjoint when he was serving as Foreign Minister under Paul Doumer's presidency. In 1933, Moulin was appointed sous-préfet of Thonon-les-Bains, parallel to his function of head of Cot's cabinet of in the Air Ministry under President Albert Lebrun. On 19 January 1934, Moulin was appointed sous-préfet of Montargis, but he did not assume the office and chose to remain under Cot. In the first half of April Moulin was appointed to the Seine préfecture and, on 1 July, he took his place as secretary general in Somme, in Amiens. In 1936, he was once more named chief of cabinet of Cot's Air Ministry of the Popular Front. In that capacity, Moulin was involved in Cot's efforts to assist the Second Spanish Republic by sending it planes and pilots. For the Istres-Damas-Le Bourget race, he presented the winners with their prize; Benito Mussolini's son was one of those winners. He became France's youngest préfet in the Aveyron département, based in the commune of Rodez, in January 1937. It has been claimed that during the Spanish Civil War, Moulin assisted with the shipment of arms from the Soviet Union to Spain. A more commonly-accepted version of events is that he used his position in the French air ministry to deliver planes to the Spanish Republican forces.

French Resistance

In January 1939, Moulin was appointed prefect of the Eure-et-Loir department. After war against Germany was declared, he asked multiple times to be demoted because "[his] place is not at the rear, at the head of a rural departement".[9][10] Against the opinion of the Minister of the Interior, he asked to be transferred to the military school of Issy-Les-Moulineaux, near Paris. The minister forced him to return to Chartres, where he had trouble ensuring the safety of the population. When the Germans got close to Chartres, he wrote to his parents, "If the Germans — who are able to do anything — make me say dishonorable words, you already know, it is not the truth".[11]

He was arrested by the Germans on 17 June 1940, as he refused to sign a false declaration that three Senegalese tirailleurs had committed atrocities, killing civilians in La Taye. In fact, those civilians had been killed by German bombings.[12][13] Beaten and imprisoned because he refused to comply, Moulin attempted suicide by cutting his throat with a piece of broken glass. That left him with a scar he would often hide with a scarf, which is the image of Jean Moulin remembered today. He was found by a guard and taken to hospital for treatment.[14][15] Because he was a Radical, he was dismissed by the Vichy regime, led by Marshal Philippe Pétain on 2 November 1940,[16][2] along with all other left-wing préfets. He then began writing his diary, First Battle, in which he relates his resistance against the Nazis in Chartres, which was later published at the Liberation and prefaced by de Gaulle.

Having decided not to collaborate, he left Chartres for Saint-Andiol, Bouches-du-Rhône, to study and join the French Resistance, and he decided to negotiate with Free France.[17] He started to use the name Joseph Jean Mercier and went to Marseille, where he met other résistants, including Henri Frenay and Antoine Sachs.

Moulin reached London in September 1941 after travelling through Spain and Portugal, and he was received on 24 October by De Gaulle, who wrote about Moulin, "A great man. Great in every way".[18]

Moulin summarised the state of the French Resistance to de Gaulle. Part of the Resistance considered him too ambitious, but de Gaulle had confidence in his network and skills. He gave Moulin the assignment of co-ordinating and unifying the various Resistance groups, a hard mission that would take time and effort to accomplish.[19] On 1 January 1942, Moulin parachuted into the Alpilles and met with the leaders of the resistance groups, under the codenames Rex and Max:

- Henri Frenay (Combat)

- Emmanuel d'Astier (Libération)

- Jean-Pierre Lévy (Francs-tireurs)

- Pierre Villon (Front national, not to be confused with the later political party of the same name)

- Pierre Brossolette (Comité d'action socialiste)

He succeeded to the extent that the first three of these resistance leaders and their groups came together to form the Mouvements Unis de la Résistance (MUR) in January 1943. The next month, Moulin returned to London, accompanied by Charles Delestraint, who led the new Armée secrète, which grouped the MUR's military wings together. Moulin left London on 21 March 1943, with orders to form the Conseil national de la Résistance (CNR), a difficult task since the five resistance movements involved, besides the three already in the MUR, wanted to retain their independence. The first meeting of the CNR took place in Paris on 27 May 1943. Some historians consider Moulin one of the most important figures in the French Resistance because of his actions in unifying and organizing the various resistance groups, which had previously been operating in an independent and uncoordinated manner. He was also instrumental in obtaining the cooperation of the Communist resistance groups, who had been reluctant to accept De Gaulle as their leader, because Moulin was known as a left-wing republican.[20]

In his work in shepherding the Resistance, Moulin was aided by his private administrative assistant, Laure Diebold.

Betrayal and death

On 21 June 1943, he was arrested at a meeting with fellow Resistance leaders in the home of Frédéric Dugoujon in Caluire-et-Cuire, a suburb of Lyon, as were Dugoujon, Henri Aubry (alias Avricourt and Thomas), Raymond Aubrac, Bruno Larat (alias Xavier-Laurent Parisot), André Lassagne (alias Lombard), Colonel Albert Lacaze, Colonel Émile Schwarzfeld (alias Blumstein) and René Hardy (alias Didot).

He was, with the other Resistance leaders, sent to Montluc Prison in Lyon in which he was detained until the beginning of July. Tortured daily in Lyon by Klaus Barbie, the head of the Gestapo there, and later more briefly in Paris, Moulin never revealed anything to his captors. According to witnesses, Moulin and his men had their fingernails removed using hot needles as spatulas. In addition, his fingers were placed on the door frames and the doors were closed again and again until his knuckles were broken. They then tightened the handcuffs until they penetrated his skin and broke the bones in his wrists. Because he still refused to speak, they beat him until his face was unrecognizable and he fell into a coma. Afterwards, Barbie ordered Moulin to be placed in an office and to be shown to all members of the Resistance not to collaborate with the Nazis. The last time he was seen alive, he was still in a coma and his head was yellow, swollen and wrapped in bandages, as was the description given by Christian Pineau, fellow prisoner and another member of the Resistance.[21][22][23][24][25] He is believed to have died near Metz on a train headed for Germany[26] from injuries that were reportedly sustained in a suicide attempt.

Barbie alleged that suicide was the cause, and Moulin biographer Patrick Marnham supports that explanation.

René Hardy was caught and released by the Gestapo, who had followed him to the meeting at the doctor's house. Some believe him guilty of a deliberate act of treason; others think he was simply reckless. Two trials found him innocent. A recent television film about the life and death of Jean Moulin depicted Hardy as collaborating with the Gestapo, thus reviving the controversy. The Hardy family attempted to bring a lawsuit against the producers of the movie.

There have been many suppositions in the postwar years that Moulin was Communist. No hard evidence has ever backed up that claim. Marnham looked into the assertions but found no evidence to support them (although Communist Party members could easily have seen him as a "fellow traveller" because he had communist friends and supported the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War). As préfet, Moulin even ordered the repression of communist 'agitators' and went so far as to have police keep some of them under surveillance.[27] At the trial of Klaus Barbie in 1987, his lawyer, Jacques Vergès, made much out of speculation that Moulin was betrayed by either Communists and/or Gaullists as part of an attempt to distract attention away from the actions of his client, by making the true authors of Moulin's arrest his fellow résistants, rather than Barbie.[28] Vergès failed in his effort to acquit Barbie but succeeded in creating a vast industry of various conspiracy theories, many very fanciful, about who betrayed Moulin.[29] Leading historians, such Henri Noguères and Jean-Pierre Azéma, rejected Vergès's conspiracy theories in which Barbie was somehow less culpable than the supposed traitors who tipped him off.[29]

The British intelligence officer Peter Wright, in his 1987 book Spy Catcher, wrote that Pierre Cot was an "active Russian agent" and called his protégé Moulin a "dedicated Communist".[30] Clinton wrote that Wright based his allegations against Moulin entirely on secret documents that he claimed to have seen but which no historian has ever seen, and on conversations that he is supposed to have had decades ago with others long dead, which made his case against Moulin very "dubious".[30] Henri-Christian Giraud, the grandson of General Henri Giraud (who had been outmaneuvered by de Gaulle for the leadership of the Free French movement), hit back in his two-volume work De Gaulle et les communistes, published in 1988 and 1989, which outlined a conspiracy theory suggesting that de Gaulle had been "manipulated" by the "Soviet agent" Moulin into following the PCF's line of "national insurrection" and thereby eclipsed his grandfather, who, he maintained, should have been the rightful leader of Free France.[31] Taking up Giraud's theories, the lawyer Charles Benfredj argued in his 1990 book L'Affaire Jean Moulin: Le contre-enquête that Moulin was a Soviet agent who had not been killed by Barbie but allowed by the German government to go to the Soviet Union in 1943, where Moulin supposedly died sometime after the war.[32] Benfredj's book was published with an introduction with Jacques Soustelle, the archaeologist of Mexico and wartime Gaullist whose commitment to Algérie française had made him a bitter enemy of de Gaulle by 1959.[32] The essence of all theories about Moulin, the alleged Soviet agent, was that because de Gaulle had agreed to co-operate with the Communists during the war, all of which was Moulin's work, he had set France on the wrong course and led to him granting Algeria independence in 1962, instead of keeping Algeria in France.[33]

It has also been suggested, principally in Marnham's biography, that Moulin was betrayed by communists. Marnham points the finger specifically at Raymond Aubrac and possibly his wife, Lucie. He alleges that communists at times betrayed non-communists to the Gestapo and that Aubrac was linked to harsh actions during the purge of collaborators after the war. In 1990, Barbie, by then "a bitter dying Nazi", named Aubrac as the traitor.[34] To counteract the accusations levelled at Moulin, Daniel Cordier, his personal secretary during the war, wrote a biography of his former leader.[35] In April 1997, Vergès produced a "Barbie Testament", which he claimed that Barbie had given him ten years earlier and purported to show the Aubracs had tipped off Barbie.[36] It was timed for the publication of the book Aubrac Lyon 1943 by Gérard Chauvy, who meant to prove that the Aubracs were the ones who informed Barbie about the fateful meeting at Caluire on 21 June 1943.[35] On 2 April 1998, following a civil suit launched by the Aubracs, a Paris court fined Chauvy and his publisher, Albin Michel, for "public defamation".[37] In 1998, the French historian Jacques Baynac, in his book Les Secrets de l'affaire Jean Moulin, claimed that Moulin was planning to break with de Gaulle to recognise General Giraud, which led the Gaullists to tip off Barbie before that could happen.[38]

Legacy

Ashes that were presumed to be his were buried in Le Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris and later transferred to the Panthéon on 19 December 1964. The speech given at the transfer site by André Malraux, a writer and cabinet minister, is one of the most famous speeches in French history.

France's French education curriculum commemorates Moulin as a symbol of the French resistance and a model of civic virtuousness, moral rectitude and patriotism. As of 2015, Jean Moulin was the fifth most popular name for a French school,[39] and as of 2016 his is the third most popular French street name[40] of which 98 percent are male.[40] Lyon 3 university and a Paris metro station have also been named after him. Another member of the resistance, Antoinette Sasse, created a bequest in her will to found The Musée Jean Moulin in 1994.[41]

The fictional Jean Pierre Melville film Army of Shadows, based on a book of the same name, depicts, through the character of Luc Jardie, played by Paul Meurisse, several events in Moulin's war experience but with some inaccuracy; in the film, his homosexual male secretary is replaced by a female assistant.

In 1993, commemorative French 2, 100 and 500 franc coins were issued, showing a partial image of Moulin against the Croix de Lorraine and using a fedora-and-scarf photograph, which is well recognised in France.

See also

References

- "Jean Moulin (1899–1943)". BBC history. 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "Jean Moulin | Chemins de mémoire".

- Killing the SS: The Hunt for the Worst War Criminals in History Bill O'Reilly, Martin Dugard - 2018 - History, books.google.ie accessed 21 November 2020

- ↑ « Jean Moulin » [archive], sur saint-andiol.fr.

- Marnham, Patrick (2012). Resistance and Betrayal: The Death and Life of the Greatest Hero of the French Resistance. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1588360786.

- Jean Moulin le sacrifice du héros, La Voix du 14e

- Patrick Marnham: Army of the Night: The Life and Death of Jean Moulin, Legend of the French Resistance I.B.Tauris, 10 Aug 2015, Google Books, accessed 21 November 2020

- Peyre, Alain (2000). Jean Moulin dit Romanin (based on an exhibition of his work at the Galerie d'Art du Conseil General des Bouches-du-Rhone, Aix-En-Provence, 6 April – 25 June 2000). Arles: Actes Sud. p. 53. ISBN 978-2-7427-2690-5.

- Francis Zamponi, Nelly Bouveret et Daniel Allary, Jean Moulin : mémoires d'un homme sans voix, Éditions du Chêne, 1999, 144 p. (ISBN 2-842772407).

- Johnson, Douglas. "The Mystery of Jean Moulin", Los Angeles Times, 1 September 2002.

- Francis Zamponi, Bouveret et Allary 1999, p. 75.

- Raffael Scheck, Une saison noire : Les massacres de tirailleurs sénégalais, mai-juin 1940, Editions Tallandier, 2007, p. 121.

- "The Death of Jean Moulin: The French Resistance Gets Its Greatest Martyr".

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 page 91.

- The Devil's Agent: Life, Times and Crimes of Nazi Klaus Barbie books.google.ie, accessed 21 November 2020

- "Jean Moulin - Artiste, Préfet, Résistant - le site de sa famille - Chronologie".

- Daniel Cordier, Jean Moulin – La République des Catacombes, Gallimard, p. 62.

- ↑ Francis Zamponi, Bouveret et Allary 1999, p. 98.

- Riviera at War: World War II on the Côte d'Azur.

- Cobb, Matthew (2009). The Resistance: the French Fight Against the Nazis. London: Simon and Schuster UK.

- "Barbie and Brunner". auschwitz.dk. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "The Friendliest Interrogator Of World War II Was A German". 31 January 2014.

- Bartrop, Paul R.; Grimm, Eve E. (11 January 2019). Perpetrating the Holocaust: Leaders, Enablers, and Collaborators. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440858970 – via Google Books.

- Barbier, Mary Kathryn (11 October 2017). Spies, Lies, and Citizenship: The Hunt for Nazi Criminals. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9781612349718 – via Google Books.

- Allen, Alan (18 March 2008). American Civilian Counter-terrorist Manual: a fictional autobiography of Ronald Reagan. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 9781466981829 – via Google Books.

- Death certificate for Jean Moulin(in German) Archived 15 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Marnham, Patrick (2001). The Death of Jean Moulin: Biography of a Ghost. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6584-1. p. 104

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 pages 203–204.

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 page 204.

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 page 205.

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 pages 205–206.

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 page 206.

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 page 201.

- "Obituary:Raymond Aubrac". Daily Telegraph. 11 April 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 pages 202–203.

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 page 209.

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 pages 209–210.

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 page 210.

- De Jules Ferry à Pierre Perret, l'étonnant palmarès des noms d'écoles, de collèges et de lycées en France, Le Monde (tr. From Jules Ferry to Pierre Perret, the surprising list of names of schools, colleges and high schools in France), accessed 21 November 2020

- "Noms de rues : Jaurès et Moulin les plus donnés". Ladepeche.fr. 16 April 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "Antoinette Sasse, artiste et résistante". www.historia.fr (in French). Retrieved 18 February 2017.

Bibliography

- Baynac, Jacques. Les secrets de l'affaire Jean Moulin: Contexte, Causes Et Circonstances. Seuil: Paris, 1998. ISBN 2-02-033164-0

- Clinton, Alan. Jean Moulin, 1899–1943: the French Resistance and the Republic. Palgrave: New York, 2002. ISBN 978-0-333-76486-2

- Daniel Cordier. Jean Moulin. La République des catacombes. Gallimard: Paris, 1999. ISBN 2-07-074312-8

- Hardy, René. Derniers mots: Mémoires. Fayard: Paris, 1984. ISBN 2-213-01320-9

- Marnham, Patrick. The Death of Jean Moulin: Biography of a Ghost. John Murray: New York, 2001. ISBN 0-7126-6584-6. Also published as Resistance and Betrayal ISBN 0-375-50608-X. 2015 edition published as Army of the Night, Tauris. ISBN 9781784531089

- Moulin, Laure. Jean Moulin. Presses de la Cité: Paris, 1982. (En préface le discours de André Malraux). ISBN 2-258-01120-5

- Noguères, Henri. La vérité aura le dernier mot. Seuil: Paris, 1985 ISBN 2-02-008683-2

- Péan, Pierre. Vies et morts de Jean Moulin. Fayard: Paris, 1998. ISBN 2-213-60257-3

- Storck-Cerruty, Marguerite. J'étais la femme de Jean Moulin. Régine Desforges: Paris, 1977. (Avec lettre-préface de Robert Aron, de l'Académie française). ISBN 2-901980-74-0

- Sweets, John F.. The Politics of Resistance in France, 1940-1944: A History of the Mouvements Unis de la Résistance. Northern Illinois University Press: De Kalb, 1976. ISBN 0-87580-061-0

- Taussat, Robert (1998). Jean Moulin : la constance et l'honneur de la République. Rodez: Fil d'Ariane. ISBN 9782912470263. OCLC 49281909.