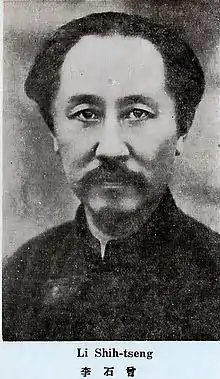

Li Shizeng

Li Shizeng (Chinese: 李石曾; Wade–Giles: Li Shih-tseng; 29 May 1881 – 30 September 1973), born Li Yuying, was an educator, promoter of anarchist doctrines, political activist, and member of the Chinese Nationalist Party in early Republican China.

Li Shizeng | |

|---|---|

Li Shizeng as pictured in The Most Recent Biographies of Important Chinese People | |

| Born | 李煜瀛 Li Yuying 29 May 1881 |

| Died | 30 September 1973 (aged 92) |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Education | Ecole Pratique d'Agriculture du Chesnoy, Sorbonne, Pasteur Institute |

| Occupation | Educator, political activist |

| Political party | |

After coming to Paris in 1902, Li took a graduate degree in chemistry and biology, and then along with Wu Zhihui and Zhang Renjie, cofounded the Chinese anarchist movement. He was a supporter of Sun Yat-sen. He organized cultural exchange between France and China, established the first factory in Europe to manufacture and sell beancurd, and created Diligent Work-Frugal Study programs which brought Chinese students to France for work in factories. In the 1920s, Li, Zhang, Wu, and Cai Yuanpei were known as the anti-communist "Four Elders" of the Chinese Nationalist Party.[1]

Youth and early career

Though his family was from Gaoyang County, Hebei, Li was brought up in Beijing. His father was Li Hongzao. Li studied foreign languages. When Li Hongzao died in 1897, the government rewarded his sons with ranks which entitled them to hold middle-level office .[2] The title for this ranking was known as Lung-Chang.[3]

In 1900, the family fled the Boxer Uprising and invasion of the Allied Armies. After their return to Beijing, Li attended a banquet at the home of a neighboring high official who had been a friend of his father. There he met Zhang Renjie, the son of a prosperous Zhejiang silk merchant whose family had purchased him a degree and who had come to the capital to arrange a suitable office. The two quickly discovered that they shared ideas for the reform of Chinese government and society, beginning a friendship which lasted the rest of their lives. When Li was chosen in 1903 as an "embassy student" to accompany China's new ambassador Sun Baoqi to Paris, Zhang had his family arrange for him to join the group as a commercial attache. Li and Zhang traveled together, stopping first in Shanghai to meet with Wu Zhihui, by then a famous radical critic of the Qing government, where they also met Wu's friend, Cai Yuanpei.[4]

Anarchism and France

At the time, since France had the reputation of being the home of revolution, Chinese officials were reluctant to sponsor study there. Li and Zhang, however, were well connected, and arrived in France, December 1902, accompanied by their wives. Ambassador Sun was indulgent and allowed Li to spend his time in intense French language study, but Li soon resigned from the embassy to enroll in a graduate program in chemistry and biology at Ecole Pratique d'Agriculture du Chesnoy in Montargis, a suburb south of Paris. In three years he earned his degree, then went to Paris for further study at the Sorbonne University and the Pasteur Institute. He announced that he would break with family tradition and would not pursue an official career. Zhang, meanwhile, began to make his fortune by starting a Paris company to import Chinese decorative art and curios.[5] Li and Zhang persuaded Wu Zhihui to come to Paris from Edinburgh, where he had been attending university lectures. Li, Zhang, and Wu did not forget their revolutionary goals. On route back to China for a visit, Zhang met the anti-Manchu revolutionary, Sun Yat-sen and promised him extensive financial support. On his return to Paris in 1907, Zhang led Li and Wu to join Sun's Tongmenghui (Chinese Revolutionary Alliance).[6]

The Paris Anarchists

The three young radicals had come in search of ideas to explain their world and of ways to change it. They soon discovered the fashionable doctrines of anarchism, which they saw as a scientific and cosmopolitan set of ideas which would bring progress to China. The key point of difference with other revolutionaries was that for them political revolution was meaningless without cultural change. A group of Chinese anarchists in Tokyo, led by Liu Shipei, favored a return to the individualist Daoism of ancient China which found government irrelevant, but for the Paris anarchists, as the historian Peter Zarrow puts it, "science was truth and truth was science." In the following years they helped anarchism to become a pervasive, perhaps dominant, strand among radical young Chinese.[7]

The Paris anarchists argued that China needed to abolish Confucian family structure, liberate women, promote moral personal behavior, and create equitable social organizations. Li wrote that "family revolution, revolution against the sages, revolution in the Three Bonds and the Five Constants would advance the cause of humanitarianism."[8] Once these goals had been accomplished, they reasoned, the minds of the people would be clear and political improvement would follow. Authoritarian government would then be unnecessary.[9]

Although these anarchists sought to overthrow Confucian orthodoxy, their assumptions resonated with the idealistic assumptions of Neo-Confucianism: that human nature is basically good; that humans do not need coercion or governments to force them to be decent to each other; and that moral self-cultivation would lead individuals to fulfill themselves within society, rather than by liberating themselves from it.[10] For these anarchists, as for late imperial Neo-Confucians, schools were a non-authoritarian instrument of personal transformation and their favored role was as teacher.[7]

In 1906 Zhang, Li, and Wu founded the Chinese anarchist organization, the World Society (世界社 Shijie she), sometimes translated as New World Society. In later years, before moving to Taiwan in 1949, the Society became a powerful financial conglomerate, but in its early phase focused on programs of education and radical change. [11]

In 1908, the World Society started a weekly journal, Xin Shiji 新世紀週報 (New Era or New Century; titled La Novaj Tempoj in Esperanto), to introduce Chinese students in France, Japan, and China to the history of European radicalism. Zhang's successful enterprise selling Chinese art funded the journal, Wu edited it, and Li was the major contributor.[5] Other contributors included Wang Jingwei, Zhang Ji, and Chu Minyi, a student from Zhejiang who accompanied Zhang Renjie back from China and would be his assistant in the years to come.[12]

Li eagerly read and translated essays by William Godwin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Élisée Reclus, and the anarchist classics of Peter Kropotkin, especially hisThe Conquest of Bread and Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. Li was struck by their arguments that cooperation and mutual aid were more powerful than the Social Darwinist forces of competition or heartless survival of the fittest.[13] Li was also impressed by conversations with the Kropotkinist writer Jean Grave, who had spent two years in prison for publishing "Society on the Brink of Death" (1892) an anarchist pamphlet.[9]

Progress was the legitimizing principle. Li wrote in 1907 that

- Progress is advance without stopping, transformation without end. There is no affair or thing that does not progress. That is the nature of evolution. That which does not progress or is tardy owes it to sickness in human beings and injury in other things. That which does away with sickness and injury is none other than revolution. Revolution is nothing but cleansing away obstacles to progress.[14]

The Paris group worked on the assumption that science and rationality would lead toward a world civilization in which China would participate on an equal basis. They espoused Esperanto, for instance, as a scientifically designed language which would lead toward a single global language superior to national ones. Their faith in moral self-cultivation led Li to adopt vegetarianism in 1908, a lifelong commitment. Yet he also believed that individuals could not liberate themselves simply by their own will, but needed strong moral examples of teachers. [15]

Xin Shijie even called for the reform of Chinese theater. Li regretted that reform had stopped at halfway measures such as introducing gas lights. He called for deeper reforms such as stage sets rather than bare stage and allowing men and women to act on the same stage. Li consulted several French friends before deciding to translate two contemporary French plays, L'Echelle, a one-act play by Edouard Norès (?-1904), which he translated as Ming bu ping, and Le Grand Soir by Leopold Kampf (1881-1913), which he translated as Ye wei yang. [16]

By 1910, Zhang Renjie, who continued to travel back and forth to China to promote business and support revolution, could no longer finance both Sun Yat-sen and the journal, which ceased publication after 121 issues.[12]

Soy factory and Work-Study program

The anarchists Li and Zhang Renjie also owned businesses to finance their political activities. As Zhang expanded his import business, Li realized that he could put his scientific training to use in manufacturing soy products. He felt that beancurd (doufu), would appeal to the French public as characteristically Chinese.[6]

In 1908 Li opened a soy factory, the Usine de la Caséo-Sojaïne, which manufactured and sold doufu (beancurd). [17][18]

The plant, housed in a brick building at 46–48 Rue Denis Papin in the suburb of La Garenne-Colombes a few miles to the north of Paris, produced a variety of soy products. There was little market for bean-curd jam, soy coffee and chocolate, eggs, or bean-curd cheese (in Gruyere, Roquefort or Camembert flavors), but soy flour and biscuits sold well.[19] The company offered free meals to Chinese students, who gathered also to discuss and debate revolutionary strategy. Sun Yat-sen visited the factory in 1909, and wrote: "My friend Li Shizeng has conducted research on soybeans and advocates eating soybean foods instead of meat." [20]

Li planned the Work-Study program as a way to bring young Chinese to France whose study would be financed by working in the beancurd factory and whose character would be uplifted by a regimen of moral instruction. This first Work-Study program eventually brought 120 workers to France. Li aimed to take these worker-students, who he called "ignorant" and "superstitious", and make them into knowledgeable and moral citizens who on their return would become models for a new China. The program instructed them in Chinese, French, and science and required them to abstain from tobacco, alcohol, and gambling.[21]

Li returned to China in 1909 to raise further capital for the factory. Again using family connections, he secured an interview with the governor of Zhili, Yang Lianpu, a friend of his father's, and secured a contribution.[22] His father-in-law, Yao Xueyuan (1843–1914), head of the salt merchants of Tianjin, solicited the national community of salt merchants for investment. .[23] In six months Li raised some $400,000. He arrived back in France with five workers (all from Gaoyang, his home district), and a supply of soybeans and coagulant.[20]

France

In 1905, while he was still a graduate student, Li presented his first paper on soy at the Second International Dairy Congress in Paris, and published it in the proceedings of the conference.[20] In 1910 he published a short treatise in Chinese on the economic and health benefits of soy beans and soy products, especially doufu, which he maintained could alleviate diabetes and arthritic pain, and then in 1912 Le Soja in French. At the annual lunch of France’s Society for Acclimatization (Société d’Acclimatation), in keeping with its tradition of introducing new foods from little-known plants, Li served a meal of vegetarian ham (jambon végétal), soy cheese (fromage de Soya), soy preserves (confitures de Soya, such as crème de marron), and soy bread (pain de Soya). [24][25]

Together with his partner L. Grandvoinnet, in 1912 Li published a 150-page pamphlet containing their series of eight earlier articles: Le soja: sa culture, ses usages alimentaires, thérapeutiques, agricoles et industriels (Soya – Its Cultivation, Dietary, Therapeutic, Agricultural and Industrial Uses; Paris: A Challamel, 1912). The soy historians William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi call it "one of the earliest, most important, influential, creative, interesting, and carefully researched books ever written about soybeans and soyfoods. Its bibliography on soy is larger than any published prior to that time."[26]

Li and the factory engineers developed and patented equipment for producing soymilk and beancurd, including the world’s first soymilk patents. Shurtleff and Aoyagi comment that their 1912 patent was "packed with original ideas, including various French-style cheeses and the world’s first industrial soy protein isolate, called Sojalithe, after its counterpart, Galalith, made from milk protein." Li claimed that Sojalithe could also be used as a substitute for ivory.[20]

Xinhai revolution

On the eve of the Xinhai revolution, Li joined Zhang Renjie in Beijing (they may have taken part in a plot to assassinate Yuan Shikai, who had edged out Sun Yat-sen from the presidency of the new republic). Wu Zhihui borrowed money from Sun to join them and other of the Paris anarchists such as Zhang Ji. Wang Jingwei, who had been jailed for an assassination attempt on a Manchu governor in 1910, was freed by the new government. These anarchists took advantage of the new political openness to practice what one historian calls "applied anarchism".[27]

Soon after their return, the group organized The Society to Advance Morality (進德會 Jinde hui), also known as the "Eight Nots", or "Eight Prohibitions Society" (八不會 Babu hui). True to its anarchist principles, the Society had no president, no officers, no regulations or means to enforce them, and no dues or fines. Each level of membership, however, had increasingly rigorous requirements. "Supporting members", the lowest level, agreed not to visit prostitutes and not to gamble. "General members" agreed in addition not to take concubines. The next higher level further agreed not to take government office—"Someone has to watch over officials"—not to become members of parliament, and not to smoke. The highest level promised in addition to abstain from alcohol and meat. These moral principles had a wide appeal among the new intelligentsia which was forming in cities and universities, but Li, in light of the Society's prohibition on holding office, turned down Sun Yat-sen's request that he join the new government, as did Wang Jingwei.[5][28]

Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement

In April 1912, still excited by the prospect of the new-born Chinese Republic, Li, Zhang Renjie, Wu Zhihui, and Cai Yuanpei founded in Beijing the Association for Frugal Study in France (留法儉學會 Liufa jianxue hui), also known as the Society for Rational French Education (la Societé Rationelle des Etudiants Chinois en France). At that time, most students who went abroad went on government scholarships to Japan, though the Chinese Educational Mission of 1872-1881 and the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program sent students to the United States. In contrast to his own experience on the 1902 program as an "embassy scholar", which involved only a handful of students from privileged families, Li hoped to welcome hundreds of working-class students into his program. [29] For Li, work-study continued to have a moral as well as an educational function. In addition to making workers more knowledgeable, work-study would eliminate their "decadent habits" and transform them into morally upright and hard-working citizens [30]

Yuan Shikai's opposition closed the program down. In September 1913, after Yuan violently suppressed Sun's "second revolution", Li and Wang Jingwei took their families to France for safety.[31] Wang lived with Li in Montargis and lectured to the Work-Study students. The bean-curd factory began to do better. Over the first five years, bean-curd sales averaged only 500 pieces (cakes) per month but increased to 10,000 a month in 1915, sometimes to more than 17,000 pieces a month. In 1916, however, wartime conditions forced the factory to close (it re-opened in 1919, when post-war milk shortages made soy milk more attractive).[32]

The outbreak of war in Europe in 1914 led the French government to recruit Chinese workers for their factories. By the end of the war, the Chinese Labor Corps in France brought more than 130,000 workers, mostly from North China villages. In June 1915, Li and his friends in Paris took advantage of this opportunity to provide schooling and training for those working in French factories. They renewed the Work-Study program, though on a different basis, involving less educated workers rather than students. By March 1916 their Paris group, the Societe Franco-Chinoise d'Education (華法教育會 Hua-Fa jiaoyuhui) was directly involved in recruiting and training these workers. They pressed the French government to give the workers technical education as well as factory work, and Li wrote extensively in the Chinese Labor Journal (Huagong zazhi), which introduced Western science, the arts, fiction, and current events. [33][34]

In 1921, after Li had returned to China, leaders of riots in Lyons against the leadership of the program were expelled from the country. The younger generation of students then became angry critics who dismissed anarchism and rejected older leaders. The Sino-French Institute did not became central to Sino-French relations.[35]

Nationalist Party and anarchism in the 1920s

In 1919 Li returned to Beijing to accept Cai Yuanpei's offer to teach science at the forward-looking Peking University and to also become president of the Sino-French University just outside the city.[31]

Although the basic slogan of the New Culture Movement was "Science and Democracy", Li was one of the few influential intellectuals to have professional training in a hard science. In keeping with anarchist opposition to religion, Li continued to use science to attack religion as superstition. When he became president of the Anti-Christian Movement of 1922 Li told the Beijing Atheists' League: "Religion is intrinsically old and corrupt: history has passed it by." He went on to make clear that as a cosmopolitan he did not oppose Christianity because it was foreign, but all religion as such:

- Why are we of the twentieth century... even debating this nonsense from primitive ages? ... As Western scholars often say, "Science and religion advance and retreat in reverse proportion"... Morality is the natural power for goodness. Religious morality, on the other hand, really works by rewards and punishment; it is the opposite of true morality.... The basic nature of all living creatures, including the human race, not only nourishes self-interest but also unfolds as support of the group. This is the root of morality.[36]

The former Paris Anarchists became a force in Sun Yat-sen's Nationalist Party as it rose to national power in the early 1920s. Zhang Renjie's Shanghai stock-market earnings made him a major financial supporter of the party and an early patron of Chiang Kai-shek. After Sun's death in 1925 and the initial success of Chiang's Northern Expedition, the Nationalists split into left and right factions. In 1927, Li Shizeng, Wu Zhihui, Cai Yuanpei, and Zhang Renjie became known as the party's Four Elders (yuan lao). As members of the Central Supervisory Committee in April 1927 they strongly supported Chiang Kai-shek over the leftist Wuhan government headed by their old colleague, Wang Jingwei, and they cheered the expulsion of all Communists and the bloody suppression of the communists and the left in Shanghai.[37]

The Four Elders had never established an independent power base within the party but relied on their personal relations, first with Sun, then with Chiang Kai-shek, in their efforts to make the Nationalist Party the instrument for their anarchist ambitions. In 1927, Li and Wu Zhihui were appointed as Chairmen of the Party, Cai Yuanpei accepted a series of offices in the new government, and Zhang Renjie was one of the powers behind Chiang's takeover after Sun's death. They encouraged their young anarchist followers to join the party, organize labor, and work for revolution. Many of these young anarchists did so but others sharply pointed out that Li had originally made the renunciation of political office a key principle; the defining goal of anarchism was to overthrow the state not join it. One critic wrote that "the moment Li and Wu entered the Guomindang they as good as stopped being anarchists."[38]

The Labor University, Palace Museum, and French university

Li indeed had on principle refused government office but he did accept cultural positions. In November 1924, Feng Yuxiang, the Nationalists' rival, captured Beijing and evicted the former emperor, Puyi, from the Forbidden City. When the Palace Museum was set up to oversee the vast art collections left by the emperors, Li was appointed Director General, and his protégé and distant relative Yi Peiji was made curator.[39][40] Deciding the disposition and even the ownership of these former imperial treasures was a challenge since many had already been sold by the eunuchs or impoverished imperial household staff. By the mid-1920s, many intellectuals and nationalists had come to recognize and strongly oppose the depredation of China's artistic heritage and the export of art by Chinese and foreign dealers. Therefore, the handling of the imperial collections in the Forbidden City was both a cultural and a political problem. The Palace Museum was opened on October 10, 1925, the anniversary of the Republican revolution. Li was forced to flee in fear for his life in 1926 when he was accused of communist sympathies but returned when KMT troops took the city in June 1928. Li served as chair of the Board of Directors until 1932 and also became sponsor of the Academia Sinica.[41]

In 1927, following bloody suppression of the communists and the left in April, Li gained preliminary support for a National Labor University (Laodong Daxue) in Shanghai. The National Labor University was to be the cornerstone of anarchism and the training ground for new leaders who would rise within the GMD. Drawing on the anarchist Work-Study experience in Europe, Li's aim was to produce a labor-intellectual who would embody the fusion in school slogan: "turn schools into fields and factories, fields and factories into schools.” [42]

Yet the result was mixed. The GMD Central Political Council approved the proposal in May and the University opened in September. Two factories had been set up by the Shanghai municipal government several years earlier, one for juvenile delinquents and homeless youth and another to provide jobs for the urban poor, but they had been shut down when the Chiang's troops took the city, leaving six-hundred young workers with no work. The new university re-opened these factories and welcomed workers and peasants to attend classes free of charge. Li, Cai Yuanpei, Zhang Renjie, Chu Minyi and seven others were appointed to the Board, and Yi Peiji, who had fled Beijing with Li, became president.[43]

The Charter for the university announced that its mission was to be the "educational organ of the laborers," and that it would be an "experiment in social-welfare and conduct surveys into working conditions." The Charter continued that students would be sent to factories and fields to "cultivate manual skills and to learn to respect hard work." That is, as one historian observes, the school was based on the assumption that "revolution should be contained in an evolutionary process" and that the goal was "cultivating personal revolutionary virtues," not social or political revolution. Even if Li had intended the school to be a revolutionary training ground, in the anti-leftist atmosphere the actual practice of the university was limited and subdued. The university was closed down in 1932.[44]

For many years Li had used his connections in France and China to build cultural relations. In 1917 Li had first urged France to return her portion of the Boxer Indemnity Fund to be used for cultural activities and educational exchange. In 1925, after long negotiations, the two governments signed an agreement. The money was funneled through Li, ensuring him a role of power for the next several decades. He may well have devoted a portion of it, together with money from his family, to support his own projects. Chief among these projects was the Sino-French University in Beijing, which Li had started in 1920 as a counterpart to the Sino-French University in Lyon, also started in 1920. The Sino-French University in Beijing at one point was so well-funded that it gave Peking University substantial help in repaying its debts.[45][46]

In 1927 the new nationalist government appointed Cai Yuanpei head of a board of universities which would replace the ministry of education. Li and Cai had been impressed with the rational organization of the French system of higher education in which, instead of random groupings, the country was divided into regional districts which did not overlap or duplicate each other's missions. Peking University was renamed Beiping University and reorganized to absorb other local universities. In 1928, Cai made Li head of the district for Beiping, but there was general resistance to the new scheme and the two old friends had a falling out. The new system was abandoned.[47]

By 1929 the anarchist attempt to prosper within the GMD reached a dead end. The Labor University, conclude historians Ming Chan and Arif Dirlik, added another dimension and constituency to the ideal of labor-learning which Li and the Paris anarchists had introduced into the revolutionary discourse, but they argue that by the 1920s the concept had been adopted by a wide range of revolutionaries, including their rivals, the Marxists.[48] The Four Elders had relied on personal relations with Chiang Kai-shek but lost traction when Chiang shifted his support to other factions, as Chiang often did when one faction became too strong. Dirlik also suggests that activist Chinese now felt, fairly or not, that the anarchist agenda was theoretical and long term, so could not compete with Communist or Nationalist programs of immediate and strong organization needed to save China. Li continued to work and write freely, but many of his activist followers were suppressed or put in jail.[49]

Later years

Accusations about the handling of Palace Museum finances began to dog Li and his protégé, Yi Peiji. To pay for ambitious cataloging and publication projects Yi had sold off gold dust, silver, silk, and clothing without government approval. In October 1933, after several years of investigations which Li had fought, a procurator brought formal charges against both men, with another round of indictments a year later and further charges against Yi in 1937. Yi fled to the Japanese concession at Tientsin and Li could move about in Shanghai and other coastal concessions only in disguise.[50][51]

In 1932, Li traveled to Geneva, Switzerland, to organize the Chinese delegation to the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations. While at Geneva he established the Sino-International Library.[52]

During World War II, Li lived for most of the time in New York, with trips to Chongqing and Kunming.[52] After the 1941 death of his first wife in Paris, he was reported to have a relation with a Jewish woman named "Ru Su" ("Mrs. Vegetarian"?), but they did not marry.[53] He served as a cochairman of the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe, an offshoot of the Bergson Group, which lobbied the US government and took out advertisements in newspapers urging American intervention to save European Jews. In 1943 and 1944 he was a featured speaker at the Committee's Emergency Conferences to Save the Jewish People of Europe.[54]

Following the war, Li returned once again to China. As Rector of the National Peiping Research Academy Li was a delegate to the First Soya Congress in Paris, March 1947. The Congress was organized by the French Bureau of Soya (Bureau Français du Soya), the Laboratory of Soya Experiments (Laboratoire d'Essais du Soya), and the France-China Association (l'Association France-Chine). As communist armies approached Beijing in 1948, Li moved to Geneva, where he and his wife remained until 1950, when Switzerland extended recognition to the People’s Republic. He then moved to Montevideo, Uruguay. After his wife died there in 1954, Li established a second home in Taiwan and resumed his role as national policy advisor to Chiang Kai-shek and a member of the Central Appraisal Committee, which superseded the Central Supervisory Committee.[55]

In 1958, one of Li's last public acts was to dedicate a middle-school in Tainan named in honor of Wu Zhihui.[56]

Li died April 3, 1973 in Taipei, aged 92. He was given a large funeral ceremony and buried there.[55]

Family and personal life

In 1897, at the age of 17, Li married Yao Tongyi, his older cousin, who died in Paris in 1941. They had two children. Li Zongwei, a son, born in 1899 in China, who married Ji Xiengzhan and had three children, Aline, Tayang and Eryang. He died in 1976. Their daughter, Li Yamei (called "Micheline"), was born in 1910 in Paris. She married Zhu Guangcai and had three children, Zhu Minyan, Zhu Minda, and Zhu Minxing.

In 1943, Li met a Mrs. "Ru Su", who is described as a Jewish woman who lived in New York. She became his partner but they did not marry. On February 14, 1946, Li married Lin Sushan in Shanghai. She died in Montevideo in 1954. Li married for the third time in 1957, to Tian Baotian in Taipei, when he was age 76-77 and she was 42.[57]

Major works

- Li, Shizeng and Paraf-Javal Kropotkin Petr Alekseevich Eltzbacher Paul Cafiero Carlo (1907). 新世紀叢書. 第壹集 (Xin Shi Ji Cong Shu. Di Yi Ji). Paris: Xin shi ji shu bao ju.

- Li, Yu-Ying, Grandvoinnet L. (1912). Le Soja: Sa Culture, Ses Usages Alimentaires, Thérapeutiques, Agricoles et Industriels. Paris: A. Challamel.

- —— (1913). 法蘭西敎育 (Falanxi Jiao Yu). Paris: 留法儉學會 Liu fa jian xue hui.

- —— (1961). 石僧筆記 (Shiseng Bi Ji). [Taipei?]: Zhongguo guo ji wen zi xue kan she.

- —— (1980). 李石曾先生文集 (Li Shizeng Xiansheng Wenji). Taipei: 中國國民黨中央委員會黨史委員會 Zhongguo Guomindang zhongyang weiyuanhui dangshi weiyuanhui.

- Biblioteca Sino-Internacional (Montevideo, Uruguay), 黄淵泉, 國立中央圖書館, 中國國際圖書館中文舊籍目錄, 國立中央圖書館, 1984

- Zhongguo wuzhengfu zhuyi he Zhongguo shehuidang [Chinese Anarchism and the Chinese Socialist Party]. Nanjing: Jiangsu renmin chubanshe, 1981.

Notes

- Boorman (1968), pp. 319–321.

- Boorman (1968), pp. 319–320.

- http://www.soyinfocenter.com/books/144

- Zarrow (1990), pp. 73–74.

- Scalapino (1961).

- Boorman (1968), p. 319.

- Zarrow (1990), pp. 156–157.

- Dirlik (1991), p. 98.

- Zarrow (1990), pp. 76–80.

- Zarrow (1990), pp. 240–242.

- He (2014), pp. -52–60.

- Bailey (2014), p. 24.

- Bailey (2014), p. 24.

- Dirlik (1991), p. 100.

- Levine (1993), p. 30–32.

- Tschanz (2007), pp. 92–94, 96, 100.

- Shurtleff (2011), pp. 6, 23, 37, 56, 57.

- 林海音 (Lin, Haiyin) (1971). 中國豆腐 (Zhongguo Dou Fu). Taibei Shi: Chun wen xue chu ban she. p. 125

- Shurtleff (2011), pp. 6, 56.

- Shurtleff (2011), p. 6.

- Bailey (2014), p. 25–26.

- Bailey (1988), p. 444.

- Kwan (2001), p. 107.

- Li (1912).

- Shurtleff (2011), pp. 7, 84.

- Shurtleff (2011), p. 7.

- Zarrow (1990), p. 188.

- Dirlik (1991), p. 120.

- Bailey (1988), pp. 445–447.

- Bailey (1988), p. 445.

- Boorman (1968), p. 320.

- Shurtleff (2011), p. 7, 8.

- Xu (2011), pp. 200–203.

- Levine (1993), p. 25–29.

- Levine (1993), pp. 121–134.

- Zarrow (1990), p. 156-157.

- Boorman (1968), pp. 321, 319.

- Dirlik (1991), p. 249.

- National Palace Museum Present/Former Leaders

- Köster, Hermann (1936). "The Palace Museum of Peiping". Monumenta Serica. 2 (1): 168. doi:10.1080/02549948.1936.11745017. JSTOR 40726337.

- Boorman (1968), pp. 320–321.

- Dirlik (1991), p. 261-262.

- Chan (1991), pp. 72–74.

- Yeh (1990), pp. 355–56 n. 87.

- He (2014), pp. 57–59.

- Shurtleff (2011), pp. 9, 123.

- Yeh (1990), p. 168.

- Chan (1991), p. 270.

- Dirlik (1991), p. 268.

- "Yi P'ei-chi", in Howard Boorman, ed. Biographical Dictionary of Republican China Vol IV (New York: Columbia University Press, 1971), pp. 55–56.

- Yeh (1990) p. 356 n. 87; Bai, Yu (1981). "Li Shizeng, Xiao Yu, Yu Gugong Daobao an (Li Zhizeng, Xiao Yu, and the Case of Stolen Treasure in the Palace Museum)". 传记文学 Zhuanji Wenxue. 38 (5): 106–112.

- Boorman (1968), p. 321.

- Shurtleff (2011).

- "Teaching the Chinese About the Holocaust", Rafael Medoff, Jewish Ledger, November 5, 2010

- Shurtleff (2011), p. 9.

- 私立稚暉初級中學創始人 教育部中部辦公室

- Shurtleff (2011), pp. 8–9.

References and further reading

- Bailey, Paul (1988). "The Chinese Work-Study Movement in France". China Quarterly. 115 (115): 441–461. doi:10.1017/S030574100002751X.

- —— (2014), "Cultural Productions in a New Global Space: Li Shizeng and the New Chinese Francophile Project in The Early Twentieth Century", in Lin, Pei-yin; Weipin Tsai (eds.), Print, Profit, and Perception: Ideas, Information and Knowledge in Chinese Societies, 1895–1949, Leiden: Brill, pp. 17–38, ISBN 9789004259102

- —— (1991). Reform the People: Changing Attitudes Towards Popular Education in Early 20th-Century China. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-0218-6., esp. Ch. 6, "The Work-Study Movement."

- "Li Shih-tseng", in Boorman, Howard L.; et al., eds. (1968). Biographical Dictionary of Republican China Volume II. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 319–321..

- Chan, Ming K. and Arif Dirlik (1991). Schools into Fields and Factories : Anarchists, the Guomindang, and the National Labor University in Shanghai, 1927–1932. Durham N.C.: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1154-2.

- Dirlik, Arif (1991). Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07297-9.

- He, Yan (2014), "Overseas Chinese in France and the World Society: Culture, Business, State, and National Connections, 1906–1949", in Leutner; Mechthild Goikhman Izabella (eds.), State, Society and Governance in Republican China, Münster: LIT Verlag, pp. 49–63, ISBN 978-3-643-90471-3

- Kwan, Man Bun (2001). The Salt Merchants of Tianjin: State-Making and Civil Society in Late Imperial China. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2275-7.

- Levine, Marilyn Avra (1993). The Found Generation: Chinese Communists in Europe During the Twenties. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97240-8.

- Scalapino, Robert A. and George T. Yu (1961). The Chinese Anarchist Movement. Berkeley: Center for Chinese Studies, Institute of International Studies, University of California. At The Anarchist Library (Free Download). The online version is unpaginated.

- Shurtleff, William Aoyagi Akiko (2011). Li Yu-Ying (Li Shizeng) History of His Work with Soyfoods and Soybeans in France, and His Political Career in China and Taiwan (1881–1973): Extensively Annotated Bibliography and Sourcebook (PDF). Lafayette, CA: Soyinfo Center. ISBN 978-1-928914-35-8.

- Tschanz, Dietrich (2007). "Where East and West Meet: Chinese Revolutionaries, French Orientalists, and Intercultural Theater in 1910s Paris" (PDF). Taiwan Journal of East Asian Studies. 4 (1): 89–108. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.

- Xu, Guoqi (2011). Strangers on the Western Front: Chinese Workers in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04999-4.

- Yeh, Wen-Hsin (1990). The Alienated Academy : Culture and Politics in Republican China, 1919–1937. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01585-1.

- Zarrow, Peter Gue (1990). Anarchism and Chinese Political Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-07138-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Li Shizeng. |