Esperanto

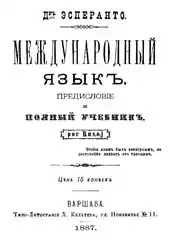

Esperanto (/ˌɛspəˈrɑːntoʊ/ or /ˌɛspəˈræntoʊ/)[6][7] is the most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. It was created by Polish ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof in 1887. Zamenhof first described the language in The International Language, which he published in five languages under the pseudonym "Doktoro Esperanto". (This book is often nicknamed in Esperanto as la Unua Libro i.e. The First Book.) The word esperanto translates into English as "one who hopes".[8]

| Esperanto | |

|---|---|

| esperanto[1] | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [espeˈranto] ( |

| Created by | L. L. Zamenhof |

| Date | 1887 |

| Setting and usage | International: most parts of the world |

| Users | Native: estimated 1,000 to several thousand (2016)[2][3] L2 users: estimates range from 63,000[4] to two million[5] |

| Purpose | |

Early form | |

| Latin script (Esperanto alphabet) Esperanto Braille | |

| Signuno | |

| Sources | Vocabulary from Romance and Germanic languages, grammar from Slavic languages |

| Official status | |

| Regulated by | Akademio de Esperanto |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | eo |

| ISO 639-2 | epo |

| ISO 639-3 | epo |

epo | |

| Glottolog | espe1235 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAB-da |

Esperantujo: 120 countries worldwide | |

Esperanto flag |

|---|

Zamenhof's goal was to create an easy and flexible language that would serve as a universal second language to foster world peace and international understanding, and to build a "community of speakers", as he believed that one could not have a language without such a community.

His original title for the language was simply "the international language" (la lingvo internacia), but early speakers grew fond of the name Esperanto and began to use it as the name for the language just two years after its creation. The name quickly gained prominence and has been used as an official name ever since.[9]

In 1905, Zamenhof published Fundamento de Esperanto ("Foundation[Note 1] of Esperanto") as a definitive guide to the language. Later that year, French Esperantists organized with his participation the first World Esperanto Congress, an ongoing annual conference, in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France. The first congress ratified the Declaration of Boulogne, which established several foundational premises for the Esperanto movement; one of its pronouncements is that Fundamento de Esperanto is the only obligatory authority over the language; another is that the Esperanto movement is exclusively a linguistic movement and that no further meaning can ever be ascribed to it. Zamenhof also proposed to the first congress that an independent body of linguistic scholars should steward the future evolution of Esperanto, foreshadowing the founding of the Akademio de Esperanto (in part modelled after the Académie française), which was established soon thereafter. Since 1905, the congress has been held in a different country every year, with the exceptions of the years during the World Wars and restricted to online-only during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. In 1908, a group of young Esperanto speakers led by the Swiss Hector Hodler established the Universal Esperanto Association in order to provide a central organization for the global Esperanto community.

Esperanto grew throughout the 20th century, both as a language and as a linguistic community. Despite speakers facing persecution in regimes such as Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union under Stalin,[10] Esperanto speakers continued to establish organizations and publish periodicals tailored to specific regions and interests. In 1954, the United Nations granted official support to Esperanto as an international auxiliary language in the Montevideo Resolution.[11] Several writers have contributed to the growing body of Esperanto literature, including William Auld, who received the first nomination for the Nobel Prize in Literature for a literary work in Esperanto in 1999, followed by two more in 2004 and 2006. Those writing in Esperanto are also officially represented in PEN International, the worldwide writers association, through Esperanto PEN Centro.[12]

Kevin Grieves investigated how Esperanto periodicals from over a century ago, carrying messages of world peace and greater understanding among cultures to all parts of the world. In his study he illuminates an actively engaged international community articulating a sentiment of transnational common identity that can be seen as a precursor to today’s notions of participatory journalism, such as Global Voices (also in Esperanto).[13]

The development of Esperanto has continued unabated into the 21st century. The advent of the Internet has had a significant impact on the language, as learning it has become increasingly accessible on platforms such as Duolingo, and as speakers have increasingly networked on platforms such as Amikumu.[14] With up to two million speakers, a small portion of whom are native speakers,[5] it is the most widely spoken constructed language in the world.[15] Although no country has adopted Esperanto officially,[Note 2] Esperantujo ("Esperanto-land") is the name given to the collection of places where it is spoken, and the language is widely employed in world travel, correspondence, cultural exchange, conventions, literature, language instruction, television, and radio.[16] Some people have chosen to learn Esperanto for its purported help in third language acquisition, like Latin.

While many of its advocates continue to hope for the day that Esperanto becomes officially recognized as the international auxiliary language, some (including raŭmistoj) have stopped focusing on this goal and instead view the Esperanto community as a "stateless diasporic linguistic group" ("senŝtata diaspora lingva kolektivo") based on freedom of association, with a culture worthy of preservation, based solely on its own merit.[16]

Three goals

Zamenhof had three goals, as he wrote in Unua Libro:

- "To render the study of the language so easy as to make its acquisition mere play to the learner."[17]

- "To enable the learner to make direct use of his knowledge with people of any nationality, whether the language be universally accepted or not; in other words, the language is to be directly a means of international communication."

- "To find some means of overcoming the natural indifference of mankind, and disposing them, in the quickest manner possible, and en masse, to learn and use the proposed language as a living one, and not only in last extremities, and with the key at hand."[18]

According to the database Ethnologue (published by the Summer Institute of Linguistics), up to two million people worldwide, to varying degrees, speak Esperanto,[5][19] including about 1,000 to 2,000 native speakers who learned Esperanto from birth.[20] The Universal Esperanto Association has more than 5500 members in 120[21] countries. Its usage is highest in Europe, East Asia, and South America.[22]

Esperanto and the Internet

Lernu!

Lernu! is one of the most popular online learning platforms for Esperanto. Already in 2013, the "lernu.net" site reported 150,000 registered users and had between 150,000 and 200,000 visitors each month.[23] Lernu currently has 320,000 registered users, who are able to view the site's interface in their choice of 24 languages – Catalan, Chinese (both simplified and traditional characters) Danish, English, Esperanto, Finnish, French, Georgian, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Kirundi, Kiswahili, Norwegian (Bokmål), Persian, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, Swedish and Ukrainian; a further five languages — Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Indonesian and Spanish – have at least 70 percent of the interface localized; nine additional languages – Dutch, Greek, Japanese, Korean, Lithuanian, Polish, Thai, Turkish and Vietnamese – are in varying stages of completing the interface translation. About 50,000 lernu.net users possess at least a basic understanding of Esperanto.

Wikipedia

With over 292,000 articles, Esperanto Wikipedia (Vikipedio) is the 32nd-largest Wikipedia, as measured by the number of articles,[24] and is the largest Wikipedia in a constructed language.[25] About 150,000 users consult the Vikipedio regularly, as attested by Wikipedia's automatically aggregated log-in data, which showed that in October 2019 the website has 117,366 unique individual visitors per month, plus 33,572 who view the site on a mobile device instead.[26]

Online Translate

On February 22, 2012, Google Translate added Esperanto as its 64th language.[27] On July 25, 2016, Yandex Translate added Esperanto as a language.[28]

Duolingo

On May 28, 2015, the language learning platform Duolingo launched a free Esperanto course for English speakers.[29] On March 25, 2016, when the first Duolingo Esperanto course completed its beta-testing phase, that course had 350,000 people registered to learn Esperanto through the medium of English. As of 27 May 2017, over one million users had begun learning Esperanto on Duolingo;[30] by July 2018 the number of learners had risen to 1.36 million. On July 20, 2018, Duolingo changed from recording users cumulatively to reporting only the number of "active learners" (i.e., those who are studying at the time and have not yet completed the course),[31] which as of October 2019 stands at 294,000 learners.[32] On October 26, 2016, a second Duolingo Esperanto course, for which the language of instruction is Spanish, appeared on the same platform[33] and which as of October 2019 has a further 277,000 students.[34] A third Esperanto course, taught in Brazilian Portuguese, began its beta-testing phase on May 14, 2018, and as of October 2019, 232,000 people[35] are using this course. A fourth Esperanto course, taught in French, began its beta-testing phase in July 2020,[36] and a fifth course, taught in Mandarin Chinese, is in development.[37]

Esperanto is now one of 36 courses that Duolingo teaches through English, one of ten courses taught through Spanish, one of six courses taught through Portuguese, and one of six courses taught through French.

History

Creation

Esperanto was created in the late 1870s and early 1880s by L. L. Zamenhof, a Polish-Jewish ophthalmologist from Białystok, then part of the Russian Empire but now part of Poland. According to Zamenhof, he created the language to reduce the "time and labour we spend in learning foreign tongues" and to foster harmony between people from different countries: "Were there but an international language, all translations would be made into it alone ... and all nations would be united in a common brotherhood."[18] His feelings and the situation in Białystok may be gleaned from an extract from his letter to Nikolai Borovko:[38]

"The place where I was born and spent my childhood gave direction to all my future struggles. In Białystok the inhabitants were divided into four distinct elements: Russians, Poles, Germans and Jews; each of these spoke their own language and looked on all the others as enemies. In such a town a sensitive nature feels more acutely than elsewhere the misery caused by language division and sees at every step that the diversity of languages is the first, or at least the most influential, basis for the separation of the human family into groups of enemies. I was brought up as an idealist; I was taught that all people were brothers, while outside in the street at every step I felt that there were no people, only Russians, Poles, Germans, Jews and so on. This was always a great torment to my infant mind, although many people may smile at such an 'anguish for the world' in a child. Since at that time I thought that 'grown-ups' were omnipotent, so I often said to myself that when I grew up I would certainly destroy this evil."

— L. L. Zamenhof, in a letter to Nikolai Borovko, ca. 1895

"It was invented in 1887 and designed that anyone could learn it in a few short months. Dr. Zamenhof lived on Dzika Street, No.9, which was just around the corner from the street on which we lived. Brother Afrum was so impressed with that idea that he learned Esperanto in a very short time at home from a little book. He then bought many dozens of them and gave them out to relatives, friends, just anyone he could, to support that magnificent idea for he felt that this would be a common bond to promote relationships with fellow men in the world. A group of people had organized and sent letters to the government asking to change the name of the street where Dr. Zamenhof lived for many years when he invented Esperanto, from Dzika to Zamenhofa. They were told that a petition with a large amount of signatures would be needed. That took time so they organized demonstrations carrying large posters encouraging people to learn the universal language and to sign the petitions... About the same time, in the middle of the block was marching a huge demonstration of people holding posters reading "Learn Esperanto", "Support the Universal language", "Esperanto the language of hope and expectation", "Esperanto the bond for international communication" and so on, and many "Sign the petitions". I will never forget that rich-poor, sad-glad parade and among all these people stood two fiery red tramway cars waiting on their opposite lanes and also a few doroszkas with their horses squeezed in between. Such a sight it was. Later a few blocks were changed from Dzika Street to Dr. Zamenhofa Street and a nice monument was erected there with his name and his invention inscribed on it, to honor his memory.

— Autobiography of Tema Kipnis, Jewish refugee from Poland

About his goals Zamenhof wrote that he wants mankind to "learn and use", "en masse", "the proposed language as a living one".[18] The goal for Esperanto to become a general world language was not the only goal of Zamenhof; he also wanted to "enable the learner to make direct use of his knowledge with persons of any nationality, whether the language be universally accepted or not; in other words, the language is to be directly a means of international communication."[18]

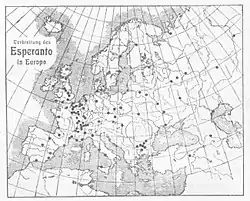

After some ten years of development, which Zamenhof spent translating literature into Esperanto as well as writing original prose and verse, the first book of Esperanto grammar was published in Warsaw on July 26, 1887. The number of speakers grew rapidly over the next few decades, at first primarily in the Russian Empire and Central Europe, then in other parts of Europe, the Americas, China, and Japan. In the early years, speakers of Esperanto kept in contact primarily through correspondence and periodicals, but in 1905 the first World Congress of Esperanto speakers was held in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France. Since then world congresses have been held in different countries every year, except during the two World Wars. Since the Second World War, they have been attended by an average of more than 2,000 people and up to 6,000 people.

Zamenhof's name for the language was simply Internacia Lingvo ("International Language").[39]

Later history

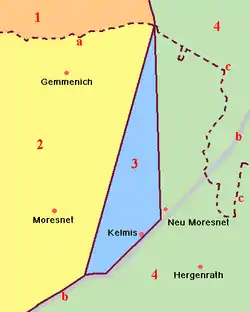

The autonomous territory of Neutral Moresnet, between what is today Belgium and Germany, had a sizable proportion of Esperanto-speakers among its small and multi-ethnic population. There was a proposal to make Esperanto its official language.

However, neither Belgium nor Prussia (now within Germany) had ever surrendered its original claim to it. Around 1900, Germany in particular was taking a more aggressive stance towards the territory and was accused of sabotage and of obstructing the administrative process in order to force the issue. It was the First World War, however, that was the catalyst that brought about the end of neutrality. On August 4, 1914, Germany invaded Belgium, leaving Moresnet at first "an oasis in a desert of destruction".[40] In 1915, the territory was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia, without international recognition. Germany having lost the war, Moresnet was returned to Belgium, and today it is the German-speaking Belgian municipality of Kelmis.

After the Great War, a great opportunity seemed to arise for Esperanto when the Iranian delegation to the League of Nations proposed that it be adopted for use in international relations, following a report by Nitobe Inazō, an official delegate of the League of Nations during the 13th World Congress of Esperanto in Prague.[41] Ten delegates accepted the proposal with only one voice against, the French delegate, Gabriel Hanotaux. Hanotaux opposed all recognition of Esperanto at the League, from the first resolution on December 18, 1920 and subsequently through all efforts during the next three years.[42] Hanotaux did not like how the French language was losing its position as the international language and saw Esperanto as a threat, effectively wielding his veto power to block the decision. However, two years later, the League recommended that its member states include Esperanto in their educational curricula. The French government retaliated by banning all instruction in Esperanto in France's schools and universities .[43][44] The French Ministry Of Instruction said that "French and English would perish and the literary standard of the world would be debased".[44] Nonetheless, many people see the 1920s as the heyday of the Esperanto movement. Anarchism as a political movement was very supportive during this time of anationalism as well as of the Esperanto language.[45]

Fran Novljan was one of the chief promoters of Esperanto in former Yugoslavia. He was among the founders of the Croatian Prosvjetnoga saveza (Educational Alliance), of which he was first secretary, and organized Esperanto institutions in Zagreb. Novljan collaborated with Esperanto newspapers and magazines, and was the author of the Esperanto textbook Internacia lingvo esperanto i Esperanto en tridek lecionoj.[46][47]

Official repression

Esperanto attracted the suspicion of many states. The situation was especially pronounced in Nazi Germany, Francoist Spain up until the 1950s, and in the Soviet Union under Stalin, from 1937 to 1956.

In Nazi Germany, there was a motivation to forbid Esperanto because Zamenhof was Jewish, and due to the internationalist nature of Esperanto, which was perceived as "Bolshevist". In his work, Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler specifically mentioned Esperanto as an example of a language that could be used by an international Jewish conspiracy once they achieved world domination.[10] Esperantists were killed during the Holocaust, with Zamenhof's family in particular singled out to be killed.[48] The efforts of a minority of German Esperantists to expel their Jewish colleagues and overtly align themselves with the Reich were futile, and Esperanto was legally forbidden in 1935. Esperantists in German concentration camps did, however, teach Esperanto to fellow prisoners, telling guards they were teaching Italian, the language of one of Germany's Axis allies.[49]

In Imperial Japan, the left wing of the Japanese Esperanto movement was forbidden, but its leaders were careful enough not to give the impression to the government that the Esperantists were socialist revolutionaries, which proved a successful strategy.[50]

After the October Revolution of 1917, Esperanto was given a measure of government support by the new workers' states in the former Russian Empire and later by the Soviet Union government, with the Soviet Esperanto Association being established as an officially recognized organization.[51] In his biography on Joseph Stalin, Leon Trotsky mentions that Stalin had studied Esperanto.[52] However, in 1937, at the height of the Great Purge, Stalin completely reversed the Soviet government's policies on Esperanto; many Esperanto speakers were executed, exiled or held in captivity in the Gulag labour camps. Quite often the accusation was: "You are an active member of an international spy organisation which hides itself under the name of 'Association of Soviet Esperantists' on the territory of the Soviet Union." Until the end of the Stalin era, it was dangerous to use Esperanto in the Soviet Union, despite the fact that it was never officially forbidden to speak Esperanto.[53]

Fascist Italy allowed the use of Esperanto, finding its phonology similar to that of Italian and publishing some tourist material in the language.

During and after the Spanish Civil War, Francoist Spain suppressed anarchists, socialists and Catalan nationalists for many years, among whom the use of Esperanto was extensive,[54] but in the 1950s the Esperanto movement was again tolerated.[55]

Official use

Esperanto has not been a secondary official language of any recognized country, but it entered the education system of several countries such as Hungary[56] and China.[57]

There were plans at the beginning of the 20th century to establish Neutral Moresnet, in central-western Europe, as the world's first Esperanto state. In addition, the self-proclaimed artificial island micronation of Rose Island, near Italy in the Adriatic Sea, used Esperanto as its official language in 1968, and another micronation, the extant Republic of Molossia, near Dayton, Nevada, uses Esperanto as an official language alongside English.[58]

The Chinese government has used Esperanto since 2001 for daily news on china.org.cn. China also uses Esperanto in China Radio International and for the internet magazine El Popola Ĉinio.[59]

The Vatican Radio has an Esperanto version of its website.[60]

The United States Army has published military phrase books in Esperanto,[61] to be used from the 1950s until the 1970s in war games by mock enemy forces. A field reference manual, FM 30-101-1 Feb. 1962, contained the grammar, English-Esperanto-English dictionary, and common phrases.

Esperanto is the working language of several non-profit international organizations such as the Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda, a left-wing cultural association which had 724 members in over 85 countries in 2006.[62] There is also Education@Internet, which has developed from an Esperanto organization; most others are specifically Esperanto organizations. The largest of these, the Universal Esperanto Association, has an official consultative relationship with the United Nations and UNESCO, which recognized Esperanto as a medium for international understanding in 1954.[63][64] The World Esperanto Association collaborated in 2017 with UNESCO to deliver an Esperanto translation[65] of its magazine UNESCO Courier (Unesko Kuriero en Esperanto).

Esperanto is also the first language of teaching and administration of the International Academy of Sciences San Marino.[66]

The League of Nations made attempts to promote teaching Esperanto in member countries, but the resolutions were defeated mainly by French delegates who did not feel there was a need for it.[67]

In the summer of 1924, the American Radio Relay League adopted Esperanto as its official international auxiliary language,[68] and hoped that the language would be used by radio amateurs in international communications, but its actual use for radio communications was negligible.

All the personal documents sold by the World Service Authority, including the World Passport, are written in Esperanto, together with English, French, Spanish, Russian, Arabic, and Chinese.[69]

Achievement of its creator's goals

Zamenhof had the goal to "enable the learner to make direct use of his knowledge with persons of any nationality, whether the language be universally accepted or not",[18] as he wrote in 1887. The language is currently spoken by people living in more than 100 countries; there are about two thousand Esperanto native speakers and probably some hundred thousand people use the language regularly.

On the other hand, one common criticism made is that Esperanto has failed to live up to the hopes of its creator, who dreamed of it becoming a universal second language.[70][71] In this regard it has to be noted that Zamenhof was well aware that it might take much time, maybe even many centuries, to get this hope into reality. In his speech at the World Esperanto Congress in Cambridge in 1907 he said, "we hope that earlier or later, maybe after many centuries, on a neutral language foundation, understanding one each other, the nations will build ... a big family circle."[72]

Linguistic properties

Classification

Esperanto's phonology, grammar, vocabulary, and semantics are based on the Indo-European languages spoken in Europe. The sound inventory is essentially Slavic, as is much of the semantics, whereas the vocabulary derives primarily from the Romance languages, with a lesser contribution from Germanic languages and minor contributions from Slavic languages and Greek. Pragmatics and other aspects of the language not specified by Zamenhof's original documents were influenced by the native languages of early authors, primarily Russian, Polish, German, and French. Paul Wexler proposes that Esperanto is relexified Yiddish, which he claims is in turn a relexified Slavic language,[73] though this model is not accepted by mainstream academics.[74]

Esperanto has been described as "a language lexically predominantly Romanic, morphologically intensively agglutinative, and to a certain degree isolating in character".[75] Typologically, Esperanto has prepositions and a pragmatic word order that by default is subject–verb–object. Adjectives can be freely placed before or after the nouns they modify, though placing them before the noun is more common. New words are formed through extensive prefixing and suffixing.

Phonology

Esperanto typically has 22 to 24 consonants, depending on the phonemic analysis and individual speaker, five vowels, and two semivowels that combine with the vowels to form six diphthongs. (The consonant /j/ and semivowel /i̯/ are both written j, and the uncommon consonant /dz/ is written with the digraph dz,[76] which is the only consonant that doesn't have its own letter.) Tone is not used to distinguish meanings of words. Stress is always on the second-last vowel in fully Esperanto words unless a final vowel o is elided, which occurs mostly in poetry. For example, familio "family" is [fa.mi.ˈli.o], with the stress on the second i, but when the word is used without the final o (famili’), the stress remains on the second i: [fa.mi.ˈli].

Consonants

The 23 consonants are:

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||||||||

| Affricate | t͡s | (d͡z) | t͡ʃ | d͡ʒ | ||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | (x) | h | ||||||

| Approximant | l | j | (w) | |||||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||||||

There is some degree of allophony:

- The sound /r/ is usually an alveolar trill [r], but can also be a uvular trill [ʀ],[77] a uvular fricative [ʁ],[78] and an alveolar approximant [ɹ].[79] Many other forms such as an alveolar tap [ɾ] are done and accepted in practice.

- The /v/ is normally pronounced like English v, but may be pronounced [ʋ] (between English v and w) or [w], depending on the language background of the speaker.

- A semivowel /u̯/ normally occurs only in diphthongs after the vowels /a/ and /e/, not as a consonant /w/.

- Common, if debated, assimilation includes the pronunciation of nk as [ŋk] and kz as [ɡz].

A large number of consonant clusters can occur, up to three in initial position (as in stranga, "strange") and five in medial position (as in ekssklavo, "former slave"). Final clusters are uncommon except in unassimilated names, poetic elision of final o, and a very few basic words such as cent "hundred" and post "after".

Vowels

Esperanto has the five vowels found in such languages as Spanish, Swahili, Modern Hebrew, and Modern Greek.

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Mid | e | o |

| Open | a | |

There are also two semivowels, /i̯/ and /u̯/, which combine with the monophthongs to form six falling diphthongs: aj, ej, oj, uj, aŭ, and eŭ.

Since there are only five vowels, a good deal of variation in pronunciation is tolerated. For instance, e commonly ranges from [e] (French é) to [ɛ] (French è). These details often depend on the speaker's native language. A glottal stop may occur between adjacent vowels in some people's speech, especially when the two vowels are the same, as in heroo "hero" ([he.ˈro.o] or [he.ˈro.ʔo]) and praavo "great-grandfather" ([pra.ˈa.vo] or [pra.ˈʔa.vo]).

Orthography

The Esperanto alphabet is based on the Latin script, using a one-sound-one-letter principle, except for [d͡z]. It includes six letters with diacritics: ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ (with circumflex), and ŭ (with breve). The alphabet does not include the letters q, w, x, or y, which are only used when writing unassimilated terms or proper names.

The 28-letter alphabet is:

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper case | A | B | C | Ĉ | D | E | F | G | Ĝ | H | Ĥ | I | J | Ĵ | K | L | M | N | O | P | R | S | Ŝ | T | U | Ŭ | V | Z |

| Lower case | a | b | c | ĉ | d | e | f | g | ĝ | h | ĥ | i | j | ĵ | k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | ŝ | t | u | ŭ | v | z |

| IPA phoneme | a | b | t͡s | t͡ʃ | d | e | f | ɡ | d͡ʒ | h | x | i | j=i̯ | ʒ | k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | ʃ | t | u | w=u̯ | v | z |

All unaccented letters are pronounced approximately as in the IPA, with the exception of c.

Esperanto j and c are used in a way familiar to speakers of German and many Slavic languages, but unfamiliar to most English speakers: j has a y sound [j~i̯], as in yellow and boy, and c has a ts sound [t͡s], as in hits or the zz in pizza. In addition, Esperanto g is always hard, as in give, and Esperanto vowels are pronounced as in Spanish.

The accented letters are:

- Ĉ is pronounced like English ch in chatting

- Ĝ is pronounced like English g in gem

- Ĥ is pronounced like the ch in German Bach or in the Scottish Gaelic, Scots and Scottish Standard English loch. It is also found sometimes in Scouse as the 'k' in book and 'ck' in chicken.

- Ĵ is pronounced like the s in English fusion or the J in French Jacques

- Ŝ is pronounced like English sh

- Ŭ is pronounced like English w and is primarily used after vowels (e.g. antaŭ)

Writing diacritics

Even with the widespread adoption of Unicode, the letters with diacritics (found in the "Latin-Extended A" section of the Unicode Standard) can cause problems with printing and computing, because they are not found on most physical keyboards and are left out of certain fonts.

There are two principal workarounds to this problem, which substitute digraphs for the accented letters. Zamenhof, the inventor of Esperanto, created an "h-convention", which replaces ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ, and ŭ with ch, gh, hh, jh, sh, and u, respectively.[80] If used in a database, a program in principle could not determine whether to render, for example, ch as c followed by h or as ĉ, and would fail to render, for example, the word senchava properly, unless its component parts were intentionally separated, as in e.g. senc·hava. A more recent "x-convention" has gained ground since the advent of computing. This system replaces each diacritic with an x (not part of the Esperanto alphabet) after the letter, producing the six digraphs cx, gx, hx, jx, sx, and ux.

There are computer keyboard layouts that support the Esperanto alphabet, and some systems use software that automatically replaces x- or h-convention digraphs with the corresponding diacritic letters (for example, Amiketo[81] for Microsoft Windows, Mac OS X, and Linux, Esperanta Klavaro for Windows Phone,[82] and Gboard and AnySoftKeyboard for Android).

Criticisms are made of the letters with circumflex diacritics, which some find odd or cumbersome, along with their being invented specifically for Esperanto rather than borrowed from existing languages; as well as being arguably unnecessary, as for example with the use of ĥ instead of x and ŭ instead of w.[83] However Zamenhof did not choose those letters arbitrarily: in fact, they were inspired by Czech letters with caron diacritic, but replacing the caron by a circumflex for the ease of those who had (or could avail themselves of) a French typewriter (with dead-key circumflex); the Czech ž was replaced by ĵ by analogy with the French j. The letter ŭ on the other hand comes from the u-breve as used in Latin prosody and (as ў) in Belorussian Cyrillic, and French typewriters can render it approximately as the French letter ù.

Grammar

Esperanto words are mostly derived by stringing together roots, grammatical endings, and at times prefixes and suffixes. This process is regular so that people can create new words as they speak and be understood. Compound words are formed with a modifier-first, head-final order, as in English (compare "birdsong" and "songbird," and likewise, birdokanto and kantobirdo). Speakers may optionally insert an o between the words in a compound noun if placing them together directly without the o would make the resulting word hard to say or understand.

The different parts of speech are marked by their own suffixes: all common nouns end in -o, all adjectives in -a, all derived adverbs in -e, and all verbs except the jussive (or imperative) end in -s, specifically in one of six tense and mood suffixes, such as the present tense -as; the jussive mood, which is tenseless, ends in -u. Nouns and adjectives have two cases: nominative for grammatical subjects and in general, and accusative for direct objects and (after a preposition) to indicate direction of movement.

Singular nouns used as grammatical subjects end in -o, plural subject nouns in -oj (pronounced [oi̯] like English "oy"). Singular direct object forms end in -on, and plural direct objects with the combination -ojn ([oi̯n]; rhymes with "coin"): -o indicates that the word is a noun, -j indicates the plural, and -n indicates the accusative (direct object) case. Adjectives agree with their nouns; their endings are singular subject -a ([a]; rhymes with "ha!"), plural subject -aj ([ai̯], pronounced "eye"), singular object -an, and plural object -ajn ([ai̯n]; rhymes with "fine").

|

|

The suffix -n, besides indicating the direct object, is used to indicate movement and a few other things as well.

The six verb inflections consist of three tenses and three moods. They are present tense -as, future tense -os, past tense -is, infinitive mood -i, conditional mood -us and jussive mood -u (used for wishes and commands). Verbs are not marked for person or number. Thus, kanti means "to sing", mi kantas means "I sing", vi kantas means "you sing", and ili kantas means "they sing".

|

|

Word order is comparatively free. Adjectives may precede or follow nouns; subjects, verbs and objects may occur in any order. However, the article la "the", demonstratives such as tiu "that" and prepositions (such as ĉe "at") must come before their related nouns. Similarly, the negative ne "not" and conjunctions such as kaj "and" and ke "that" must precede the phrase or clause that they introduce. In copular (A = B) clauses, word order is just as important as in English: "people are animals" is distinguished from "animals are people".

Vocabulary

The core vocabulary of Esperanto was defined by Lingvo internacia, published by Zamenhof in 1887. This book listed 900 roots; these could be expanded into tens of thousands of words using prefixes, suffixes, and compounding. In 1894, Zamenhof published the first Esperanto dictionary, Universala Vortaro, which had a larger set of roots. The rules of the language allowed speakers to borrow new roots as needed; it was recommended, however, that speakers use most international forms and then derive related meanings from these.

Since then, many words have been borrowed, primarily (but not solely) from the European languages. Not all proposed borrowings become widespread, but many do, especially technical and scientific terms. Terms for everyday use, on the other hand, are more likely to be derived from existing roots; komputilo "computer", for instance, is formed from the verb komputi "compute" and the suffix -ilo "tool". Words are also calqued; that is, words acquire new meanings based on usage in other languages. For example, the word muso "mouse" has acquired the meaning of a computer mouse from its usage in many languages (English mouse, French souris, Dutch muis, Spanish ratón, etc.). Esperanto speakers often debate about whether a particular borrowing is justified or whether meaning can be expressed by deriving from or extending the meaning of existing words.

Some compounds and formed words in Esperanto are not entirely straightforward; for example, eldoni, literally "give out", means "publish", paralleling the usage of certain European languages (such as German herausgeben, Dutch uitgeven, Russian издать izdat'). In addition, the suffix -um- has no defined meaning; words using the suffix must be learned separately (such as dekstren "to the right" and dekstrumen "clockwise").

There are not many idiomatic or slang words in Esperanto, as these forms of speech tend to make international communication difficult—working against Esperanto's main goal.

Instead of derivations of Esperanto roots, new roots are taken from European languages in the endeavor to create an international language.[84]

Sample text

The following short extract gives an idea of the character of Esperanto.[85] (Pronunciation is covered above; the Esperanto letter j is pronounced like English y.)

- Esperanto:

- «En multaj lokoj de Ĉinio estis temploj de la drako-reĝo. Dum trosekeco oni preĝis en la temploj, ke la drako-reĝo donu pluvon al la homa mondo. Tiam drako estis simbolo de la supernatura estaĵo. Kaj pli poste, ĝi fariĝis prapatro de la plej altaj regantoj kaj simbolis la absolutan aŭtoritaton de la feŭda imperiestro. La imperiestro pretendis, ke li estas filo de la drako. Ĉiuj liaj vivbezonaĵoj portis la nomon drako kaj estis ornamitaj per diversaj drakofiguroj. Nun ĉie en Ĉinio videblas drako-ornamentaĵoj, kaj cirkulas legendoj pri drakoj.»

- English translation:

- In many places in China, there were temples of the dragon-king. During times of drought, people would pray in the temples that the dragon-king would give rain to the human world. At that time the dragon was a symbol of the supernatural creature. Later on, it became the ancestor of the highest rulers and symbolised the absolute authority of a feudal emperor. The emperor claimed to be the son of the dragon. All of his personal possessions carried the name "dragon" and were decorated with various dragon figures. Now dragon decorations can be seen everywhere in China and legends about dragons circulate.

Simple phrases

Below are listed some useful Esperanto words and phrases along with IPA transcriptions:

| English | Esperanto | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| Hello | [sa.ˈlu.ton] | |

| Yes | [ˈjes] | |

| No | [ˈne] | |

| Good morning | [ˈbo.nan ma.ˈte.non] | |

| Good evening | [ˈbo.nan ves.ˈpe.ron] | |

| Good night | [ˈbo.nan ˈnok.ton] | |

| Goodbye | [ˈdʒis (la re.ˈvi.do)] | |

| What is your name? | Kiel vi nomiĝas? | [ˈki.o ˌes.tas ˌvi.a ˈno.mo] [ˈki.εl vi nɔ.ˈmi.dʒas] |

| My name is Marco. | [ˌmi.a ˈno.mo ˌes.tas ˈmar.ko] | |

| How are you? | [ˈki.el vi ˈfar.tas] | |

| I am well. | [mi ˈfar.tas ˈbo.ne] | |

| Do you speak Esperanto? | [ˈtʃu vi pa.ˈro.las ˌes.pe.ˈran.ton] | |

| I don't understand you | [mi ˌne kom.ˈpre.nas ˌvin] | |

| All right | [ˈbo.ne] / [en ˈor.do] | |

| Okay | ||

| Thank you | [ˈdan.kon] | |

| You're welcome | [ˌne.dan.ˈkin.de] | |

| Please | [bon.ˈvo.lu] / [mi ˈpε.tas] | |

| Forgive me/Excuse me | [par.ˈdo.nu ˈmin] | |

| Bless you! | [ˈsa.non] | |

| Congratulations! | [ɡra.ˈtu.lon] | |

| I love you | [mi ˈa.mas ˌvin] | |

| One beer, please | [ˈu.nu bi.ˈe.ron, mi ˈpe.tas] | |

| Where is the toilet? | [ˈki.e ˈes.tas ˈla ˌne.tse.ˈse.jo] | |

| What is that? | [ˈki.o ˌes.tas ˈti.o] | |

| That is a dog | [ˈti.o ˌes.tas ˈhun.do] | |

| We will love! | [ni ˈa.mos] | |

| Peace! | [ˈpa.tson] | |

| I am a beginner in Esperanto. | [mi ˈes.tas ˌko.men.ˈtsan.to de ˌes.pe.ˈran.to] |

Origin

The vocabulary, orthography, phonology, and semantics are all thoroughly European. The vocabulary, for example, draws about three-quarters from Romance languages, with the rest split between Greek, English and German. The syntax has Germanic and Slavic tendencies, with internal tensions when these disagree; the semantics and phonology have been said to be Slavic.[86]

Education

Esperanto speakers learn the language through self-directed study, online tutorials, and correspondence courses taught by volunteers. More recently, free teaching websites like lernu! and Duolingo have become available.

Esperanto instruction is rarely available at schools, including four primary schools in a pilot project under the supervision of the University of Manchester, and by one count at a few universities.[87] However, outside China and Hungary, these mostly involve informal arrangements rather than dedicated departments or state sponsorship. Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest had a department of Interlinguistics and Esperanto from 1966 to 2004, after which time instruction moved to vocational colleges; there are state examinations for Esperanto instructors.[88][89] Additionally, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poland offers a diploma in Interlinguistics.[90] The Senate of Brazil passed a bill in 2009 that would make Esperanto an optional part of the curriculum in public schools, although mandatory if there is demand for it. As of 2015 the bill is still under consideration by the Chamber of Deputies.[91][92][93]

In the United States, Esperanto is notably offered as a weekly evening course at Stanford University's Bechtel International Center. Conversational Esperanto, The International Language, is a free drop-in class that is open to Stanford students and the general public on campus during the academic year.[94] With administrative permission, Stanford Students can take the class for two credits a quarter through the Linguistics Department. "Even four lessons are enough to get more than just the basics," the Esperanto at Stanford website reads.

Esperanto-USA suggests that Esperanto can be learned in anywhere from one quarter of the amount of time required for other languages.[95]

Third-language acquisition

Four primary schools in Britain, with 230 pupils, are currently following a course in "propaedeutic Esperanto"—that is, instruction in Esperanto to raise language awareness and accelerate subsequent learning of foreign languages—under the supervision of the University of Manchester. As they put it,

- Many schools used to teach children the recorder, not to produce a nation of recorder players, but as a preparation for learning other instruments. [We teach] Esperanto, not to produce a nation of Esperanto-speakers, but as a preparation for learning other languages.[96]

Studies have been conducted in New Zealand,[97] the United States,[98][99][100] Germany,[101] Italy[102] and Australia.[103] The results of these studies were favorable and demonstrated that studying Esperanto before another foreign language expedites the acquisition of the other, natural language. This appears to be because learning subsequent foreign languages is easier than learning one's first foreign language, whereas the use of a grammatically simple and culturally flexible auxiliary language like Esperanto lessens the first-language learning hurdle. In one study,[104] a group of European secondary school students studied Esperanto for one year, then French for three years, and ended up with a significantly better command of French than a control group, who studied French for all four years.

Community

Geography and demography

Esperanto is by far the most widely spoken constructed language in the world.[105] Speakers are most numerous in Europe and East Asia, especially in urban areas, where they often form Esperanto clubs.[106] Esperanto is particularly prevalent in the northern and central countries of Europe; in China, Korea, Japan, and Iran within Asia;[50] in Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico in the Americas;[5] and in Togo in Africa.[107]

Countering a common criticism against Esperanto, the statistician Svend Nielsen has found there to be no significant correlation between the number of Esperanto speakers and similarity of a given national mother language to Esperanto. He concludes that Esperanto tends to be more popular in countries that are rich, with widespread Internet access and that tend to contribute more to science and culture. Linguistic diversity within a country was found to have a slight inverse correlation with Esperanto popularity.[108]

Number of speakers

An estimate of the number of Esperanto speakers was made by Sidney S. Culbert, a retired psychology professor at the University of Washington and a longtime Esperantist, who tracked down and tested Esperanto speakers in sample areas in dozens of countries over a period of twenty years. Culbert concluded that between one and two million people speak Esperanto at Foreign Service Level 3, "professionally proficient" (able to communicate moderately complex ideas without hesitation, and to follow speeches, radio broadcasts, etc.).[109] Culbert's estimate was not made for Esperanto alone, but formed part of his listing of estimates for all languages of more than one million speakers, published annually in the World Almanac and Book of Facts. Culbert's most detailed account of his methodology is found in a 1989 letter to David Wolff.[110] Since Culbert never published detailed intermediate results for particular countries and regions, it is difficult to independently gauge the accuracy of his results.

In the Almanac, his estimates for numbers of language speakers were rounded to the nearest million, thus the number for Esperanto speakers is shown as two million. This latter figure appears in Ethnologue. Assuming that this figure is accurate, that means that about 0.03% of the world's population speak the language. Although it is not Zamenhof's goal of a universal language, it still represents a level of popularity unmatched by any other constructed language.

Marcus Sikosek (now Ziko van Dijk) has challenged this figure of 1.6 million as exaggerated. He estimated that even if Esperanto speakers were evenly distributed, assuming one million Esperanto speakers worldwide would lead one to expect about 180 in the city of Cologne. Van Dijk finds only 30 fluent speakers in that city, and similarly smaller-than-expected figures in several other places thought to have a larger-than-average concentration of Esperanto speakers. He also notes that there are a total of about 20,000 members of the various Esperanto organizations (other estimates are higher). Though there are undoubtedly many Esperanto speakers who are not members of any Esperanto organization, he thinks it unlikely that there are fifty times more speakers than organization members.[106]

Finnish linguist Jouko Lindstedt, an expert on native-born Esperanto speakers, presented the following scheme[111] to show the overall proportions of language capabilities within the Esperanto community:

- 1,000 have Esperanto as their native language.

- 10,000 speak it fluently.

- 100,000 can use it actively.

- One million understand a large amount passively.

- Ten million have studied it to some extent at some time.

In 2017, doctoral student Svend Nielsen estimated around 63,000 Esperanto speakers worldwide, taking into account association memberships, user-generated data from Esperanto websites and census statistics. This number, however, was disputed by statistician Sten Johansson, who questioned the reliability of the source data and highlighted a wide margin of error, the latter point with which Nielsen agrees. Both have stated, however, that this new number is likely more realistic than some earlier projections.[4]

In the absence of Dr. Culbert's detailed sampling data, or any other census data, it is impossible to state the number of speakers with certainty. According to the website of the World Esperanto Association:

Native speakers

Native Esperanto speakers, denaskuloj, have learned the language from birth from Esperanto-speaking parents.[112] This usually happens when Esperanto is the chief or only common language in an international family, but sometimes occurs in a family of Esperanto speakers who often use the language.[113] The 15th edition of Ethnologue cited estimates that there were 200 to 2000 native speakers in 1996,[114] but these figures were removed from the 16th and 17th editions.[115] The current online version of Ethnologue gives "L1 users: 1,000 (Corsetti et al 2004)".[116] As of 1996, there were approximately 350 attested cases of families with native Esperanto speakers (which means there were around 700 Esperanto speaking natives in these families, not calculating older native speakers).[117]

Culture

Esperantists can access an international culture, including a large body of original as well as translated literature. There are more than 25,000 Esperanto books, both originals and translations, as well as several regularly distributed Esperanto magazines. In 2013 a museum about Esperanto opened in China.[118] Esperantists use the language for free accommodations with Esperantists in 92 countries using the Pasporta Servo or to develop pen pals through Esperanto Koresponda Servo.[119]

Every year, Esperantists meet for the World Congress of Esperanto (Universala Kongreso de Esperanto).[120][121]

Historically, much Esperanto music, such as Kaj Tiel Plu, has been in various folk traditions.[122] There is also a variety of classical and semi-classical choral music, both original and translated, as well as large ensemble music that includes voices singing Esperanto texts. Lou Harrison, who incorporated styles and instruments from many world cultures in his music, used Esperanto titles and/or texts in several of his works, most notably La Koro-Sutro (1973). David Gaines used Esperanto poems as well as an excerpt from a speech by Dr. Zamenhof for his Symphony No. One (Esperanto) for mezzo-soprano and orchestra (1994–98). He wrote original Esperanto text for his Povas plori mi ne plu (I Can Cry No Longer) for unaccompanied SATB choir (1994).

There are also shared traditions, such as Zamenhof Day, and shared behaviour patterns. Esperantists speak primarily in Esperanto at international Esperanto meetings.

Detractors of Esperanto occasionally criticize it as "having no culture". Proponents, such as Prof. Humphrey Tonkin of the University of Hartford, observe that Esperanto is "culturally neutral by design, as it was intended to be a facilitator between cultures, not to be the carrier of any one national culture". The late Scottish Esperanto author William Auld wrote extensively on the subject, arguing that Esperanto is "the expression of a common human culture, unencumbered by national frontiers. Thus it is considered a culture on its own."[123]

Esperanto heritage

A number of Esperanto associations also advance education in and about Esperanto and aim to preserve and promote the culture and heritage of Esperanto.[124] Poland added Esperanto to its list of Intangible heritage in 2014.[125]

Notable authors in Esperanto

Some authors of works in Esperanto are:

|

Popular culture

In the futuristic novel Lord of the World by Robert Hugh Benson, Esperanto is presented as the predominant language of the world, much as Latin is the language of the Church.[126] A reference to Esperanto appears in the science-fiction story War with the Newts by Karel Čapek, published in 1936. As part of a passage on what language the salamander-looking creatures with human cognitive ability should learn, it is noted that "...in the Reform schools, Esperanto was taught as the medium of communication." (P. 206). [127]

Esperanto has been used in a number of films and novels. Typically, this is done either to add the exotic flavour of a foreign language without representing any particular ethnicity, or to avoid going to the trouble of inventing a new language. The Charlie Chaplin film The Great Dictator (1940) showed Jewish ghetto shop signs in Esperanto. Two full-length feature films have been produced with dialogue entirely in Esperanto: Angoroj, in 1964, and Incubus, a 1965 B-movie horror film which is also notable for starring William Shatner shortly before he began working on Star Trek. In Captain Fantastic (2016) there is a dialogue in Esperanto. Finally, Mexican film director Alfonso Cuarón has publicly shown his fascination for Esperanto,[128] going as far as naming his film production company Esperanto Filmoj ("Esperanto Films").

Science

.jpg.webp)

In 1921 the French Academy of Sciences recommended using Esperanto for international scientific communication.[129] A few scientists and mathematicians, such as Maurice Fréchet (mathematics), John C. Wells (linguistics), Helmar Frank (pedagogy and cybernetics), and Nobel laureate Reinhard Selten (economics) have published part of their work in Esperanto. Frank and Selten were among the founders of the International Academy of Sciences in San Marino, sometimes called the "Esperanto University", where Esperanto is the primary language of teaching and administration.[130][131]

A message in Esperanto was recorded and included in Voyager 1's Golden Record.

Commerce and trade

Esperanto business groups have been active for many years. The French Chamber of Commerce did research in the 1920s and reported in The New York Times in 1921 that Esperanto seemed to be the best business language.[132]

Goals of the movement

Zamenhof had three goals, as he wrote already in 1887: to create an easy language, to create a language ready to use "whether the language be universally accepted or not" and to find some means to get many people to learn the language.[18] So Zamenhof's intention was not only to create an easy-to-learn language to foster peace and international understanding as a general language, but also to create a language for immediate use by a (small) language community. Esperanto was to serve as an international auxiliary language, that is, as a universal second language, not to replace ethnic languages. This goal was shared by Zamenhof among Esperanto speakers at the beginning of the movement.[133] Later, Esperanto speakers began to see the language and the culture that had grown up around it as ends in themselves, even if Esperanto is never adopted by the United Nations or other international organizations.[129]

Esperanto speakers who want to see Esperanto adopted officially or on a large scale worldwide are commonly called finvenkistoj, from fina venko, meaning "final victory".[134] It has to be noted that there are two kinds of "finvenkismo"–"desubismo" and "desuprismo"; the first aims to spread Esperanto between ordinary people ("desube", from below) aiming to form a steadily growing community of Esperanto speakers. The second aims to act from above ("desupre"), beginning with politicians. Zamenhof considered the first way to have a better perspective, as "for such affairs as ours, governments come with their approval and help usually only, when everything is already completely finished".[135]

Those who focus on the intrinsic value of the language are commonly called raŭmistoj, from Rauma, Finland, where a declaration on the short-term improbability of the fina venko and the value of Esperanto culture was made at the International Youth Congress in 1980.[136] However the "Manifesto de Raŭmo" clearly mentions the intention to further spread the language: "We want to spread Esperanto to put into effect its positive values more and more, step by step".[137]

In 1996 the Prague Manifesto was adopted at the annual congress of the World Esperanto Association (UEA); it was subscribed by individual participants and later by other Esperanto speakers. More recently, language-learning apps like Duolingo and Amikumu have helped to increase the amount of fluent speakers of Esperanto, and find others in their area to speak the language with.

Symbols and flags

The earliest flag, and the one most commonly used today, features a green five-pointed star against a white canton, upon a field of green. It was proposed to Zamenhof by Richard Geoghegan, author of the first Esperanto textbook for English speakers, in 1887. The flag was approved in 1905 by delegates to the first conference of Esperantists at Boulogne-sur-Mer. A version with an "E" superimposed over the green star is sometimes seen. Other variants include that for Christian Esperantists, with a white Christian cross superimposed upon the green star, and that for Leftists, with the color of the field changed from green to red.[138]

In 1987, a second flag design was chosen in a contest organized by the UEA celebrating the first centennial of the language. It featured a white background with two stylised curved "E"s facing each other. Dubbed the "jubilea simbolo" (jubilee symbol),[139] it attracted criticism from some Esperantists, who dubbed it the "melono" (melon) because of the design's elliptical shape. It is still in use, though to a lesser degree than the traditional symbol, known as the "verda stelo" (green star).[140]

Politics

Esperanto has been placed in many proposed political situations. The most popular of these is the Europe–Democracy–Esperanto, which aims to establish Esperanto as the official language of the European Union. Grin's Report, published in 2005 by François Grin, found that the use of English as the lingua franca within the European Union costs billions annually and significantly benefits English-speaking countries financially.[141] The report considered a scenario where Esperanto would be the lingua franca, and found that it would have many advantages, particularly economically speaking, as well as ideologically.

Left-wing currents exist in the wider Esperanto world, mostly organized through the Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda founded by French theorist Eugène Lanti.[142] Other notable Esperanto socialists include Nikolai Nekrasov and Vladimir Varankin. Both Nekrasov and Varankin were arrested during the Stalinist repressions of the late 1930s. Nekrasov was accused of being "an organizer and leader of a fascist, espionage, terrorist organization of Esperantists", and executed on October 4, 1938.[143] Varankin was executed on October 3, 1938.[144]

Oomoto

The Oomoto religion encourages the use of Esperanto among its followers and includes Zamenhof as one of its deified spirits.[145]

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith encourages the use of an auxiliary international language. `Abdu'l-Bahá praised the ideal of Esperanto, and there was an affinity between Esperantists and Baháʼís during the late 19th century and early 20th century.[146][147]

On February 12, 1913, `Abdu'l-Bahá gave a talk to the Paris Esperanto Society,

Now, praise be to God that Dr. Zamenhof has invented the Esperanto language. It has all the potential qualities of becoming the international means of communication. All of us must be grateful and thankful to him for this noble effort; for in this way he has served his fellowmen well. With untiring effort and self-sacrifice on the part of its devotees Esperanto will become universal. Therefore every one of us must study this language and spread it as far as possible so that day by day it may receive a broader recognition, be accepted by all nations and governments of the world, and become a part of the curriculum in all the public schools. I hope that Esperanto will be adopted as the language of all the future international conferences and congresses, so that all people need acquire only two languages—one their own tongue and the other the international language. Then perfect union will be established between all the people of the world. Consider how difficult it is today to communicate with various nations. If one studies fifty languages one may yet travel through a country and not know the language. Therefore I hope that you will make the utmost effort, so that this language of Esperanto may be widely spread[148]

Lidia Zamenhof, daughter of L. L. Zamenhof, became a Baháʼí around 1925.[147] James Ferdinand Morton, Jr., an early member of the Baháʼí Faith in Greater Boston, was vice-president of the Esperanto League for North America.[149] Ehsan Yarshater, the founding editor of Encyclopædia Iranica, notes how as a child in Iran he learned Esperanto and that when his mother was visiting Haifa on a Baháʼí pilgrimage he wrote her a letter in Persian as well as Esperanto.[150] At the request of 'Abdu’l-Baha, Agnes Baldwin Alexander became an early advocate of Esperanto and used it to spread the Baháʼí teachings at meetings and conferences in Japan.

Today there exists an active sub-community of Baháʼí Esperantists and various volumes of Baháʼí literature have been translated into Esperanto. In 1973, the Baháʼí Esperanto-League for active Baháʼí supporters of Esperanto was founded.[147]

Spiritism

In 1908, spiritist Camilo Chaigneau wrote an article named "Spiritism and Esperanto" in the periodic La Vie d'Outre-Tombe recommending the use of Esperanto in a "central magazine" for all spiritists and esperantists. Esperanto then became actively promoted by spiritists, at least in Brazil, initially by Ismael Gomes Braga and František Lorenz; the latter is known in Brazil as Francisco Valdomiro Lorenz, and was a pioneer of both spiritist and Esperantist movements in this country.[151]

The Brazilian Spiritist Federation publishes Esperanto coursebooks, translations of Spiritism's basic books, and encourages Spiritists to become Esperantists.[152]

Bible translations

The first translation of the Bible into Esperanto was a translation of the Tanakh or Old Testament done by L. L. Zamenhof. The translation was reviewed and compared with other languages' translations by a group of British clergy and scholars before its publication at the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1910. In 1926 this was published along with a New Testament translation, in an edition commonly called the "Londona Biblio". In the 1960s, the Internacia Asocio de Bibliistoj kaj Orientalistoj tried to organize a new, ecumenical Esperanto Bible version.[153] Since then, the Dutch Remonstrant pastor Gerrit Berveling has translated the Deuterocanonical or apocryphal books in addition to new translations of the Gospels, some of the New Testament epistles, and some books of the Tanakh or Old Testament. These have been published in various separate booklets, or serialized in Dia Regno, but the Deuterocanonical books have appeared in recent editions of the Londona Biblio.

Christianity

.jpg.webp)

Christian Esperanto organizations include two that were formed early in the history of Esperanto:

- 1910—The International Union of Catholic Esperantists. Two Roman Catholic popes, John Paul II and Benedict XVI, have regularly used Esperanto in their multilingual urbi et orbi blessings at Easter and Christmas each year since Easter 1994.[154]

- 1911—The International League of Christian Esperantists.

Individual churches using Esperanto include:

- The Quaker Esperanto Society,[155] with activities as described in an issue of "The Friend"[156]

- 1910—First Christadelphian publications in Esperanto.[157][158]

- There are instances of Christian apologists and teachers who use Esperanto as a medium. Nigerian pastor Bayo Afolaranmi's "Spirita nutraĵo"[159] ("spiritual food") Yahoo mailing list, for example, has hosted weekly messages since 2003.[160]

- Chick Publications, publisher of Protestant fundamentalist themed evangelistic tracts, has published a number of comic book style tracts by Jack T. Chick translated into Esperanto, including "This Was Your Life!" ("Jen Via Tuta Vivo!")[161]

Latter-Day Saints

The Book of Mormon has been partially translated into Esperanto, although the translation has not been officially endorsed by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[162] There exists a group of Mormon Esperantists who distribute church literature in this language.[163]

Islam

Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran called on Muslims to learn Esperanto and praised its use as a medium for better understanding among peoples of different religious backgrounds. After he suggested that Esperanto replace English as an international lingua franca, it began to be used in the seminaries of Qom. An Esperanto translation of the Qur'an was published by the state shortly thereafter.[164][165]

Modifications

Though Esperanto itself has changed little since the publication of Fundamento de Esperanto (Foundation of Esperanto) , a number of reform projects have been proposed over the years, starting with Zamenhof's proposals in 1894 and Ido in 1907. Several later constructed languages, such as Universal, Saussure, Romániço, Internasia, Esperanto sen Fleksio, and Mundolingvo, were all based on Esperanto.

In modern times, conscious attempts have been made to eliminate perceived sexism in the language, such as Riism. Many words with ĥ now have alternative spellings with k and occasionally h, so that arĥitekto may also be spelled arkitekto; see Esperanto phonology for further details of ĥ replacement. Reforms aimed at altering country names have also resulted in a number of different options, either due to disputes over suffixes or Eurocentrism in naming various countries.

Criticism

There have been numerous objections to Esperanto over the years. For example, there has been criticism that Esperanto is not neutral enough, but also that it should convey a specific culture, which would make it less neutral; that Esperanto does not draw on a wide enough selection of the world's languages, but also that it should be more narrowly European.[166][167]

Neutrality

Esperantists often argue for Esperanto as a culturally neutral means of communication. However, it is often accused of being Eurocentric.[166] This is most often noted in regard to the vocabulary, but applies equally to the orthography, phonology, and semantics, all of which are thoroughly European. The vocabulary, for example, draws about three-quarters from Romance languages, and the remainder primarily from Greek, English and German. The syntax is Romance, and the phonology and semantics are Slavic. The grammar is arguably more European than not. Critics argue that a truly neutral language would draw its vocabulary from a much wider variety of languages, so as not to give an unfair advantage to speakers of any of them. Although a truly representative sampling of the world's thousands of languages would be unworkable, a derivation from, say, the Romance, Semitic, Indic, Bantu, and Sino-Tibetan language families would strike many as being fairer than Esperanto-like solutions, as these families cover about 60% of the world's population, compared to a quarter for Romance and Germanic.

Gender-neutrality

Esperanto is frequently accused of being inherently sexist, because the default form of some nouns is masculine while a derived form is used for the feminine, which is said to retain traces of the male-dominated society of late 19th-century Europe of which Esperanto is a product.[168][169] These nouns are primarily titles and kin terms, such as sinjoro "Mr, sir" vs. sinjorino "Ms, lady" and patro "father" vs. patrino "mother". In addition, nouns that denote persons and whose definitions are not explicitly male are often assumed to be male unless explicitly made female, such as doktoro, a PhD doctor (male or unspecified) versus doktorino, a female PhD. This is analogous to the situation with the English suffix -ess, as in the words baron/baroness, waiter/waitress, etc. Esperanto pronouns are similar. The pronoun li "he" may be used generically, whereas ŝi "she" is always female.[170]

Case and number agreement

Speakers of languages without grammatical case or adjectival agreement frequently complain about these aspects of Esperanto. In addition, in the past some people found the Classical Greek forms of the plural (nouns in -oj, adjectives in -aj) to be awkward, proposing instead that Italian -i be used for nouns, and that no plural be used for adjectives. These suggestions were adopted by the Ido reform.[166][167]

Achievement of its creator's goal

One common criticism made is that Esperanto has failed to live up to the hopes of its creator, who dreamed of it becoming a universal second language.[70][71] Because people were reluctant to learn a new language which hardly anyone spoke, Zamenhof asked people to sign a promise to start learning Esperanto once ten million people made the same promise, but he "was disappointed to receive only a thousand responses."[171] and exceeding even two million has been challenging.[5]

Eponymous entities

There are some geographical and astronomical features named after Esperanto, or after its creator L. L. Zamenhof. These include Esperanto Island in Antarctica,[172] and the asteroids 1421 Esperanto and 1462 Zamenhof discovered by Finnish astronomer and Esperantist Yrjö Väisälä.

See also

- Outline of Esperanto

- Arcaicam Esperantom

- Comparison between Esperanto and Ido

- Comparison between Esperanto and Interlingua

- Comparison between Esperanto and Novial

- Distributed Language Translation

- Duolingo

- Encyclopedias in Esperanto

- EoLA

- ESP-Disk

- Esperantic Studies Foundation

- Esperanto library

- Esperanto Wikipedia

- Esperantology

- Esperantujo

- lernu!

- Indigenous Dialogues

- International English

- List of Esperanto magazines

- List of largest languages without official status

- North American Summer Esperanto Institute

- (English) Semajno de Kulturo Internacia

Notes

- In Esperanto as in English, a common metaphor based on the literal, architectural sense

- Except the 3.5 km2 (1.4 sq mi) condominium Neutral Moresnet, which existed from 1816 to 1920 as a disputed territory; but that "country" didn't itself gain international recognition.

References

- Locale Data Summary for Esperanto [eo] CLDR - Unicode Common Locale Data Repository. Retrieved September 28, 2019

- Harald Haarmann, Eta leksikono pri lingvoj, 2011, archive date March 4, 2016: Esperanto … estas lernata ankaŭ de pluraj miloj da homoj en la mondo kiel gepatra lingvo. ("Esperanto has also been learned by several thousand people in the world as a mother tongue.")

- Jouko Lindstedt, Jouko, Oftaj demandoj pri denaskaj Esperant‑lingvanoj ("Frequently asked questions about native Esperanto speakers"), archive date March 3, 2016.

- "Nova takso: 60.000 parolas Esperanton" [New estimate: 60.000 speak Esperanto] (in Esperanto). Libera Folio. February 13, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- "Esperanto" (20th ed.). Ethnologue. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0

- "Doktoro Esperanto, Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof". Global Britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc.

- Schor, p. 70

- Sutton, Geoffrey (2008). Concise Encyclopedia of the Original Literature of Esperanto, 1887–2007. Mondial. ISBN 978-1-59569-090-6.

"Hitler specifically attacked Esperanto as a threat in a speech in Munich (1922) and in Mein Kampf itself (1925). The Nazi Minister for Education banned the teaching of Esperanto on 17 May 1935 ... all Esperantists were essentially enemies of the state – serving, through their language, Jewish-internationalist aims" (pages 161–162)

- "Records of the General Conference, Eighth Session, Montevideo 1954; Resolutions" (PDF). UNESDOC Database. UNESCO.

- "PEN International – Esperanto Centre". pen-international.org. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- Kevin Grieves, Esperanto Journalism and Readers as ‘Managers’: A transnational participatory audience, Researcch Gate, feb. 2020, DOI: 10.1080/13688804.2020.1727319

- Salisbury, Josh. "'Saluton!': the surprise return of Esperanto". The Guardian. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- Zasky, Jason (July 20, 2009), "Discouraging Words", Failure Magazine, archived from the original on November 19, 2011,

But in terms of invented languages, it's the most outlandishly successful invented language ever. It has thousands of speakers – even native speakers – and that's a major accomplishment as compared to the 900 or so other languages that have no speakers. – Arika Okrent

- "Esperanta Civito – Pakto". esperantio.net.

- "After half an hour I could speak more Esperanto than Japanese, I had studied during four years in secondary school" – Richard Delamore. In: "Kiel la esperantistoj povas denove avangardi?", Kontakto 277 (2017:1), p. 20, TEJO

- L.L.Zamenhof. International Language. Warsaw. 1887

- "How Many People Speak Esperanto? - Esperanto.net".

- Corsetti, Renato; Pinto, Maria Antonietta; Tolomeo, Maria (2004). "Regularizing the regular: The phenomenon of over-regularization in Esperanto‑speaking children" (PDF). Language Problems and Language Planning. John Benjamins Publishing Company. 28 (3): 261–282. doi:10.1075/lplp.28.3.04cor. ISSN 0272-2690. OCLC 4653164382. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 21, 2015.

- "Universala Esperanto-Asocio: Kio estas UEA?". Uea.org. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- "User locations". Pasporta Servo. Archived from the original on November 15, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "La programo de la kleriga lundo en UK 2013". Universala Esperanto Asocio. Archived from the original on August 5, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "List of Wikipedias". Meta.wikimedia.org. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- "List of Wikipedias by language group". Meta.wikimedia.org. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- Bonvenon al Vikipedia ("Welcome to Wikipedia"), main page of the Esperanto-language version of Wikipedia, 4 October 2019. Accessed 4 October 2019.

- Brants, Thorsten (February 22, 2012). "Tutmonda helplingvo por ĉiuj homoj". Google Translate Blog. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- "Яндекс.Переводчик освоил 11 новых языков — Блог Переводчика". yandex.ru.

- "Esperanto for English speakers now in Beta!". Duolingo. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- "Duolingo: Incubator". Duolingo. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- Changing How We Display Learner Numbers, July 20, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Language Courses for English Speakers, 28 October 2019, Duolingo.com. Accessed 28 October 2019

- "Duolingo Language Courses". Duolingo. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- Language Courses for Spanish Speakers, 28 October 2019, Duolingo.com. Accessed 28 October 2019

- Language Courses for Portuguese Speakers, 28 October 2019, Duolingo.com. Accessed 28 October 2019

- Esperanto for French Speakers, Duolingo.com. Accessed 15 September 2020.

- Esperanto for Chinese Speakers, Duolingo.com. Accessed 15 September 2020.

- The letter is quoted in Esperanto: The New Latin for the Church and for Ecumenism, by Ulrich Matthias. Translation from Esperanto by Mike Leon and Maire Mullarney

- "Dr. Esperanto' International Language". L. Samenhof. Retrieved April 15, 2016. Facsimile of the title page of the First Book in English, 1889. "Esperanto". Ling.ohio-state.edu. January 25, 2003. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- Musgrave, George Clarke. Under Four Flags for France, 1918, p. 8

- "New EAI pages". esperanto.ie. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- Dumas, John (December 19, 2014). "Imp of the Diverse: A Dark Day for Esperanto".

- Dumas, John (July 16, 2014). "Imp of the Diverse: The French Say "Non" to Esperanto".

- Dumas, John (September 10, 2014). "Imp of the Diverse: The Danger of Esperanto".

- "Esperanto kaj anarkiismo". www.nodo50.org.

Anarkiistoj estis inter la pioniroj de la disvastigo de Esperanto. En 1905 fondiĝis en Stokholmo la unua anarkiisma Esperanto-grupo. Sekvis multaj aliaj: en Bulgario, Ĉinio kaj aliaj landoj. Anarkiistoj kaj anarki-sindikatistoj, kiuj antaŭ la Unua Mondmilito apartenis al la nombre plej granda grupo inter la proletaj esperantistoj, fondis en 1906 la internacian ligon Paco-Libereco, kiu eldonis la Internacian Socian Revuon. Paco-libereco unuiĝis en 1910 kun alia progresema asocio, Esperantista Laboristaro. La komuna organizaĵo nomiĝis Liberiga Stelo. Ĝis 1914 tiu organizaĵo eldonis multe da revolucia literaturo en Esperanto, interalie ankaŭ anarkiisma. Tial povis evolui en la jaroj antaŭ la Unua Mondmilito ekzemple vigla korespondado inter eŭropaj kaj japanaj anarkiistoj. En 1907 la Internacia Anarkiisma Kongreso en Amsterdamo faris rezolucion pri la afero de internacia lingvo, kaj venis dum la postaj jaroj similaj kongresaj rezolucioj. Esperantistoj, kiuj partoprenis tiujn kongresojn, okupiĝis precipe pri la internaciaj rilatoj de la anarkiistoj.

- Istarska enciklopedija Josip Šiklić: Novljan, Fran (pristupljeno 23. ožujka 2020.)

- Pleadin, Josip. Biografia leksikono de kroatiaj esperantistoj. Đurđevac: Grafokom 2002, p. 108-109, ISBN 953-96975-0-6

- "About ESW and the Holocaust Museum". Esperantodc.org. December 5, 1995. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- Lins, Ulrich (1988). Die gefährliche Sprache. Gerlingen: Bleicher. p. 112. ISBN 3-88350-023-2.

- Lins, Ulrich (2008). "Esperanto as language and idea in China and Japan" (PDF). Language Problems and Language Planning. John Benjamins. 32 (1): 47–60. doi:10.1075/lplp.32.1.05lin. ISSN 0272-2690. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- "Donald J. Harlow, The Esperanto Book, chapter 7". Literaturo.org. Retrieved September 29, 2016.