List of Knights Hospitaller sites

The Knights Hospitaller operated a wide network of properties in the Middle Ages from their successive seats in Jerusalem, Acre, Cyprus, Rhodes and eventually Malta. In the early 14th century, they received many properties and assets previously in the hands of the Knights Templar.

Middle East

Kingdom of Jerusalem

This includes both the Kingdom of Jerusalem and its Vassal entities.

- The eponymous hospital, in the Christian Quarter of Jerusalem's neighborhood now known as Muristan just south of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, including the Church of Saint John the Baptist, 1099-1187.[1] The Templars also held the Church of Saint Mary of the Germans for a brief period until 1244.

- The Hospitaller commandery of Saint-Jean-d'Acre, ca. 1130-1187 and 1191-1291; the Hospitallers administered the whole city of Acre from 1229 to its fall in 1291.

- Bayt Jibrin (Beth Gibelin) northwest of Hebron, 1136-1187

- the Benedictine monastery in Abu Ghosh near Jerusalem, built by the Hospitallers in 1140

- Belmont Castle by Suba near Jerusalem, 1160s-1187

- Aqua Bella (Arabic Khirbat Iqbalā), now Ein Hemed west of Jerusalem

- Arsur (Arabic Arsuf, ancient Apollonia) on the coast south of Netanya, 1261-1268

- Qalansawe (Calanson) inland from Netanya, 1128-1187 and 1191-1265

- Burgata north of Qalansawe, 1248-1265

- Tel Dothan (Castellum Beleismum or Chateau Saint-Job) southwest of Jenin, in 1187

- Qula, northeast of Ramla, in the 12th century

- Cafarlet, now Kafr Lam south of Haifa, 1232-1255

- Tel Yokneam (Caymont or Cain Mons) southeast of Haifa, 1256-1262

- Tel Afek (Recordane) east of Haifa, 1154-1291

- Taibe (Le Forbelet) in the Valley of Megiddo, until 1187

- Mount Tabor fortress, 1255-1263

- Belvoir Castle (Arabic Kawkab al-Hawa) near the Sea of Galilee, 1168-1189

- Banias (ancient Caesarea Philippi) near Mount Hermon, briefly around 1157

- Hunin (Castellum Novum or Chastel Neuf) at the Northern tip of Israel, also around 1157

County of Tripoli

- The Krak des Chevaliers (Hisn al-Akrad), the Hospitallers' major fortress in the Levant, 1142-1271

- Margat (Marqab) on the Syrian coast south of Latakia, the Knights' other major redoubt, 1186-1285

- Coliath or La Colée (Qalaat al-Qlaiaat), near the coast north of Tripoli

- Gibelacar (Hisn Ibn Akkar) in Northern Lebanon, 1170-1203

- Chastel Rouge (Qal’at Yahmur) on the coast just north of the Lebanese-Syrian border, ca. 1177-1289

- Arab al-Mulk (Belda or Beaude, in Arabic also Balda al-Milk or Beldeh) near Margat, 1160s-1271

- Qurfays (Corveis) also near Margat, until 1271

Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia

- Silifke Castle (Le Selef, ancient Seleucia) in modern Turkey, 1210-1226

- Tokmar Castle near Silifke, also from 1210

Aegean Sea Region

- the Hospital of Sampson in Constantinople, which the Hospitallers managed under the Latin Empire's rule until 1261[2]

- The Hospitallers also operated hospitals in Negroponte and Corinth[3]

- Kolossi Castle near Limassol in Cyprus, 1210-1570 with an interruption in 1306-1313. Limassol was the main seat of the Order between the fall of Acre in 1291 and the move to Rhodes in 1310

- Gastria Castle in Cyprus, from 1308

- Islands of the Dodecanese:

- Kastellorizo, 1306-1440

- Rhodes, 1306-1522 (the city of Rhodes 1310-1522)

- Smyrna, in whose conquest the Hospitallers took part and 1344 and whose defense they assumed 1374-1402

- The Principality of Achaea by lease from Joanna I of Naples, 1376-1381[4]

- Corinth, 1397-1404[5][6]

- Bodrum Castle, 1402-1523

Western Europe

References to countries below are using 21st-century borders.

France

- Grand prieuré de Saint-Gilles in Saint-Gilles, Gard, 1109-1792

- Hospital of the Holy Ghost, Montpellier, est. 1145[7]

- Château de Condat, Dordogne, since the 12th century

- Hospice of Saint John, Nice[7]

- Fort Saint-Jean (Marseille), initially built by the Hospitallers in the late 12th century

- the Maison du Temple in Paris (on the location of the Square du Temple, transferred from the Knights Templar in 1313 and held until 1790

- Grand prieuré de Toulouse, 1317-1789

- Prieuré hospitalier d’Arles, 1562-1792

- Maison des chevaliers de Saint-Jean in Colmar, initially built in 1608

Italy

- Hospital of the Holy Sepulchre and Saint John, Pisa, est. 1113[7]

- Ospedaletto in Verona, from 1154[7]

- Ospedale dei Pellegrini, Asti, from 1182[7]

- Hospital of San Sepolcro at the Ponte Vecchio, Florence, 1213-1808[7]

- Abbey of Santissima Trinità, Venosa, after 1297

- Casa dei Cavalieri di Rodi in Rome, built in the late 13th century

- Hospital of San Giovanni a Maruggio, Brindisi, from 1300[7]

- San Giovanni di Malta, Venice, transferred from the Templars in 1312

- Church of San Giovannino dei Cavalieri in Florence

- Ospedale dei Pellegrini, Naples, since 1564[7]

Iberian Peninsula

- Castle of La Muela, Spain, since 1183

- Royal Monastery of Santa María de Sigena, 1183-1936

- Igreja de Santa Luzia (Lisbon), still owned by the Order

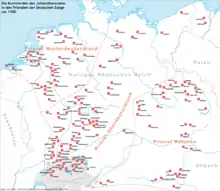

Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Poland

- Mailberg Castle, Austria, since 1146

- Münchenbuchsee Commandery, Switzerland, since 1180

- Church of Saint John of Jerusalem outside the walls in Poznań, Poland, since 1187

- Ritterhaus Bubikon near Rapperswil, Switzerland, since the 1190s

- Thunstetten Commandery, Switzerland, since the early 13th century

- Maltese Church, Vienna, since 1217

- the Principality of Heitersheim in the Breisgau, 1262-1806, Imperial Estate from 1548

- Compesières Commandry near Geneva, Switzerland, since 1270

- Sonnenburg, now Słońsk in Poland, 1426-1945

- Ordenspalais in Berlin, 1738-1811

- Kastl Abbey, 1773-1803

- Biburg Abbey, 1781-1808

- Former Jesuit college and Church of Saint George in Amberg, Bavaria (1782-1808)

Great Britain and Ireland

- Torphichen Preceptory, Scotland, since the 1140s

- St John's Jerusalem, Sutton-at-Hone, England, est. 1199

- Clerkenwell Priory in London, the Order's seat in England

- Knights Hospitaller Gallery, Quenington, England

- Hospital Church in Hospital, County Limerick

- West Peckham Preceptory, England, since the early 15th century

Tripoli and Malta

After the Ottoman conquest of Rhodes in 1522, the Knights made stops in Candia, Messina, Bacoli near Naples, and Civitavecchia. Pope Adrian VI provisionally relocated the Order in Viterbo, where they stayed from 1523 to 1527. Then at the invitation of Charles III, Duke of Savoy, they moved to Nice and nearby Villefranche. On 24 July 1530 in Bologna, Emperor Charles V granted them a new permanent base.[7][8][9]

- Tripoli, 1530-1551, where the Hospitallers' church stood on the same location as the Sidi Darghut Mosque

- Malta and Gozo, 1530-1798

Other locations

- Banate of Severin, 1247-1260

- Saint Barthélemy, Saint Kitts, Saint Croix and Northern Saint Martin, 1651-1665 during the Hospitaller colonization of the Americas

Since 1798

.jpg.webp)

Following the expulsion of the Order from Malta by Napoleon in 1798, the Order's remnants temporarily relocated in Messina until 1802, Catania until 1826, and Ferrara until 1834. Gotland was offered to the knights by Sweden in 1806, but they refused as they still hoped to reclaim sovereignty over Malta.[10] The Order then settled in its long-held properties in Rome, which were granted extraterritoriality in 1869. In that period it assumed its modern name of Sovereign Military Order of Malta.

- Villa del Priorato di Malta, Rome, Templar property transferred in 1312, with the Santa Maria del Priorato Church

- Palazzo Malta, Rome, acquired in 1630

- Church of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, Paris, since 1938

- Casa dei Cavalieri di Rodi, Rome, since 1946

- Villa Pagana in Rapallo, since 1959

- Saint John's Cavalier, part of the Fortifications of Valletta, leased since 1967 by the Order as its embassy in Malta

- Villa Malta (Cologne), since 1971

- Fort St. Angelo, Birgu, Malta (upper part), since 2001

- See also the list of diplomatic missions of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta

In Protestant countries

The Order of Saint John (Bailiwick of Brandenburg) (Johanniter) had become autonomous in 1538, and was dissolved in 1811. Since restoration in 1852 it has had its seat in Berlin until World War II, then Bad Pyrmont until 1952, Rolandseck (Haus Sölling) until 1962, Bonn until 2001, Berlin-Lichterfelde until 2004, and since 2004 Potsdam as formal seat even though the main office remains in Lichterfelde. Its activities include the Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe.

The British Order of Saint John, formed in 1831 and chartered in 1888, manages several facilities in Jerusalem undre the Saint John Eye Hospital Group, as well as the international St John Ambulance network. Its London headquarters, at St John's Gate, Clerkenwell, hosts the Museum of the Order of St John.

The Order of Saint John in Sweden was founded in 1920 following the disruption of the Johanniter in Northern Europe during World War I. Its headquarters is hosted by the House of Nobility in Stockholm.

The Order of Saint John in the Netherlands was created in 1946 in a similar development following World War II. It is headquartered at 48 Lange Voorhout in The Hague.

Johanniter International, a partnership of the four protestant Orders of St. John and their national charities, was founded in 2000 and is headquartered in Brussels.

See also

- List of Knights Templar sites

- Ordensburg

- Liste ehemaliger Johanniterkommenden

Notes

- Enrico de Lazaro (5 August 2013). "Archaeologists Find Impressive Building of Hospitaller Knights in Israel". SCI News.

- Dionysios Stathakopoulos (January 2006), "Discovering a Military Order of the Crusades: The Hospital of St. Sampson of Constantinople", Viator, 37: 255–273, doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.2.3017487

- "The Hospital of the Knights in Rhodes". Via Gallica.

- Helen Nicholson (2001). The Knights Hospitaller. Boydell & Brewer. p. 54-55.

- Mark Cartwright (24 August 2018). "Knights Hospitaller". Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- "Corinth". The Byzantine Legacy.

- Edgar Erskine Hume (1938), "Medical Work of the Knights Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem", Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine, 6 (5): 399–466, JSTOR 44438330

- "Philippe Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller". British Museum.

- Mario Buhagiar (January 2000). "The Treasure of the Knight Hospitallers in 1530: Reflections and Art Historical Considerations" (PDF). Peregrinationes. Accademia Internazionale Melitense. I.

- Stair Sainty, Guy (2000). "From the loss of Malta to the modern era". ChivalricOrders.org. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012.