Liverpool Pride

Liverpool Pride is a weekend-long festival to celebrate LGBT culture held annually at the Pier Head and Gay Quarter in Liverpool City Centre, England. The event is held on the closest weekend to 2 August, in commemoration of the death of Michael Causer, the young gay man who was murdered in the city in 2008, and has grown to become one of the largest free Gay Pride festivals in Europe with 2013's audience numbers reaching up to 75,000 people.[1][2][3]

| Liverpool Pride | |

|---|---|

Liverpool Pride 2011 at the Pier Head | |

| Frequency | Annually in August |

| Location(s) | Liverpool gay quarter, Pier Head |

| Years active | 11 |

| Inaugurated | 2010 |

| Participants | 75,000 |

| Website | Liverpool Pride website |

Liverpool Pride usually features a parade and march through the city centre on the Saturday plus a large open air festival, a number of stages, street stalls and street entertainment at the Pier Head. There is also the Liverpool Pride Fringe at the city's gay quarter itself. A ‘Chill Out Sunday’ usually follows which includes sports, arts and culture events across the city.[4]

Liverpool Pride is a registered charity run by a Board of Trustees with the stated aim of promoting equality and diversity, advancing education, and eliminating discrimination in relation to LGBT people across the six districts of Liverpool City Region: Halton, Knowsley, City of Liverpool, Sefton, St Helens and Wirral.[5]

Constitution and core values

Liverpool Pride is a not-for-profit registered charity governed by Memorandum and Articles of association and a board of 8 volunteer trustees elected by its membership at the Annual General Meetings. Membership is free and is open to anyone regardless of their sexuality, gender or sexual/gender identity so long as they have volunteered for Liverpool Pride during the previous 18 months, are an elected or appointed member of the local LGBT Steering Group, or represent a registered charity, community group or Not-for-Profit that supports Liverpool Pride's objects. The organisation is funded through contributions made from its delivery partners, through advertising and sponsorship. It also receives a significant amount of ‘in-kind’ support from organisations, fundraisers and volunteers. All funds raised go to the delivery of the festival and any surplus made goes towards the development of the next festival. Liverpool Pride also helps to support charities that share its 4 core values which are: To be inclusive, to be visible, to be free and to have a strong Liverpool/Merseyside identity.[6][7][8] The current Trustee Board are: Lucy Day (Chair), Joan Burnett, Andi Herring, John Bird, Patrick Jones, James Licence, Kim McCann and Zoran Blackie.

History

Up until 2010, Liverpool was the largest British city to not hold a Pride and it took many years of campaigning to establish a stable and lasting celebration in the city. The campaign took a significant turning point in 2008 when the newly formed Liverpool LGBT Network voted that establishing a permanent Pride in the city would be one of its key priorities."Link" (PDF). At the height of Liverpool's year as European Capital of Culture it was felt that staging a successful festival to rival those of other large UK cities was a realistic and attainable goal. Later in the year, the movement began to gather pace and was bolstered by a renewed sense of urgency and determination following the high-profile homophobic murder of Michael Causer on the outskirts of the city.

A motion in support of Liverpool Pride was put before a full meeting of Liverpool City Council by Labour Councillor Nick Small on 28 January 2009, and was approved by 74 votes to 2.[9] The City Council stated that the festival would ‘celebrate the city’s diversity, be an opportunity to raise money for charitable causes and boost the city’s visitor and night time economies’"Link" (PDF)..

The first official Pride was successfully held in the gay quarter in 2010, centered on Dale Street and Stanley Street,[10] however, in 2011 due to a funding shortfall the controversial decision was taken to relocate the main focus of the festival to the city's Pier Head.[11] Following this announcement, a public backlash ensued and sections of the local LGBT community planned to boycott the event.[12] In quick response to the anger and disappointment expressed by the community and in an attempt to salvage the situation, more than 30 businesses around Stanley Street (including the Liverpool Gay Village Business Association) rallied together in an unprecedented move and organised a complementary festival to take place in the gay district alongside the main event.[13]

Despite the overall festival proving successful in the end with visitor numbers doubling,[14] organisers came under heavy criticism from openly gay councillor Steve Radford and chair of the Village Business Association, who accused the Pride committee of "running itself aloof from the Gay Quarter and not listening to the needs of the gay community and local businesses." In an interview with Seen Magazine (a local LGBT publication), Liverpool Pride responded with claims that only a small number of local gay businesses had actually supported the event.[15]

By 2012, lessons had been learned and a much more coherent and unified approach was adopted. The Pride committee pledged that a presence would be maintained around the gay quarter thanks to a close working partnership with the Village Business Association, the collective that had organised Stanley Street Pride in 2011. Furthermore, a number of new people elected to Liverpool Pride's Board of Trustees had proven experience as organisers of the Stanley Street Pride the previous year, which meant dialogue between the local gay scene and the main Pride organisers would be much more constructive and free-flowing.[16][17]

Whilst Liverpool held its first "Official" Pride in 2010, it was not first ever in the city. Previous Prides have been held in 1979, 1990–1992, and in 1995.

Past festivals

2013: "Superheroes"

The theme for Liverpool Pride 2013 was ‘Superheroes’ voted for by 1,300 members of the public.[18] The day began with a march through the streets of Liverpool City Centre attended by more than 6000 people, and continued with stages and entertainment at the Pier Head and Gay Quarter. Overall audience figures for the festival reached a record 75,000.[19] Notable performers included:

|

|

|

2012: "Nautical But Nice"

The theme for Liverpool Pride 2012 was 'Nautical but Nice' and organisers described the event as the biggest, most ambitious and most diverse Prides ever developed in the city. Highlights included the annual Liverpool Pride March, stages at the Pier Head and gay quarter, an LGBT market, food and drink stalls, 2 for 1 tickets on Mersey Ferry cruises, open Zumba classes for all the family, and a Health and Wellbeing zone. For the first time ever in the UK, two Premier League football clubs (Liverpool and Everton) were represented in the Pride March. On Sunday 5 August, the Big Gay Brunch at Tate Liverpool and Gay Gardens at Bluecoat Chambers were held, as well as the Love Music Hate Homophobia event, the Liverpool Pride Film Festival and the Liverpool Pride arts and culture programme.[23] Audience figures reached a record 52,000.[24] Notable performers included:

|

|

|

2011: "Summer of Love"

The theme for Liverpool Pride 2011 was 'Summer of Love' and the festival was spread across two stages, a football area, over 50 market stalls, a health and wellbeing area and food outlets at the Pier Head, as well as additional celebrations in the gay quarter. It was attended by over 40,000 people.[28] Notable performers included:

|

|

|

2010: "Rainbow Circus"

The theme for Liverpool Pride 2010 was 'Rainbow Circus' and featured over 18 hours of music, dance, cabaret and performances across three stages in and around Liverpool's gay quarter. It was attended by 21,000 people and showcased over 70 acts.[32] Notable performers included:

|

|

|

Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride in the 1990s

After holding a one-off event in 1979, for many years the lesbian and gay community of Liverpool could not claim a home grown Pride of their own and instead opted to march annually in London in commemoration of the 1969 Stonewall uprisings.

However, between 1990-1992 various 'unofficial' community Pride festivals were held in the city thanks to an organised effort between the Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Action group, various arts bodies and local gay clubs.[36][37]

'Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride' as it was known then, was not in any way connected nor indeed related to the contemporary Pride festival, the main differences being that Liverpool Pride is now officially sponsored by public authorities, has a legal structure and framework, is a weekend event as opposed to week-long, and does not include references to 'Lesbian' and 'Gay' in its title through fear of alienating transgender people. Moreover, Pride in the early 90s tended to concentrate more on arts, exhibitions, culture, talks, workshops and function evenings, in contrast to the party on the scene/popstar on stage format as seen today. The events also had a strong political element and aimed to explore and challenge society's attitudes towards sexuality at that time. To put it into perspective, gay men still faced an unequal age of consent, the infamous Section 28 was still in existence, there would be no partnership or adoption rights for same sex couples for at least another decade whilst OutRage!, a UK based LGBT activist group, was just being formed.[38] Highlights of the festivals included discussions on women in the church, LGBT parenting and literature, support for gay and lesbian victims of sexual abuse and health awareness workshops. T-shirts and badges bearing the Pride logos were sold in local gay venues and at events themselves to help cover running costs (see brochure of events below).

The celebration took a brief break but returned in 1995 under the new name 'Mersey Pride', an attempt to create a more outdoor cabaret and stage type atmosphere around Pownall Square, chosen for its close proximity to The Brunswick and Time Out, two popular gay frequented pubs of the day. The occasion was modestly successful as a political statement and was attended by some 1200 revellers from across North West England, albeit attracting noticeable protests from the Christian right.[39]

In many ways, Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride of the early 90s paved the way for Homotopia, the city's modern day gay arts festival launched some 12 years later, in the sense that Homotopia took on a similar formula.[40] The Mersey Pride of 1995, however, bore a stronger resemblance to the present day festivities at the Pier Head and Gay Quarter in spite of being significantly smaller and much less mainstream.

Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride Brochure 1990

Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride Brochure 1990 Liverpool goes to London Pride 1990

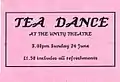

Liverpool goes to London Pride 1990 Tea Dance Ticket from Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1990

Tea Dance Ticket from Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1990 Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride Brochure 1991

Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride Brochure 1991 Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1991 Poster

Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1991 Poster Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1991 T-shirt

Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1991 T-shirt Coach ticket to London Pride 1991

Coach ticket to London Pride 1991 Badges from Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1990 & 1991

Badges from Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1990 & 1991 Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride Brochure 1992

Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride Brochure 1992 Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1992 Poster

Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1992 Poster Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1992 T-shirt

Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1992 T-shirt Benefit night at Jody's, Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1992

Benefit night at Jody's, Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1992 Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1992 tea dance programme

Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1992 tea dance programme Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1995

Liverpool Lesbian & Gay Pride 1995

Liverpool Gay Pride 1979

The first recorded Liverpool Pride commenced on 22 June 1979 and consisted of a week long celebration in remembrance of the New York Stonewall riots, which took place in the June some ten years earlier. The Liverpool event can legitimately claim to be one of the earliest known Prides to ever take place in the United Kingdom, the oldest being a march of 700 people through central London in 1972.[41][42]

References

- "Liverpool Pride 2011 – Summer of Love". Lgf.org.uk. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Liverpool Pride expected to bring 30,000 people to city for August festival". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Liverpool Pride sees 75,000 people join in the fun: Superheroes visit city for festival". Liverpool Echo. 5 August 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- "TENDER: Public Relations Management Contract". Liverpool Pride. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Liverpool Pride charity framework". Charity Commission. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Tommy McIlravey, Chair of Liverpool Pride answers your questions". Liverpool Pride. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "About Liverpool Pride". Liverpool Pride. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Membership". Liverpool Pride. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- Lesbian and Gay Foundation, 5 February 2009

- Writer, Staff. ""First Liverpool Pride 'a success", Pink News, 9th August 2010". Pinknews.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- Alan Weston (29 June 2011). ""Liverpool Pride festival moves from the city's gay quarter to Pier Head", Liverpool Echo". Liverpoolecho.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- twentyfirstcentury. ""Liverpool's relocated Pride facing boycott", Midlands Zone, 29th June 2011". Midlandszone.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- "Over 30 businesses sign up for first ever Stanley Street Pride Party > Business Features > Business". Click Liverpool. 3 August 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- "Liverpool Pride 2011 boasts a record breaking 40,000 visitors > Culture > Culture". Click Liverpool. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- "Seen Magazine, EXCLUSIVE Pride Debate". Seen Magazine. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "I ATTENDED the Liverpool Pride AGM on Tuesday and came away from it a happy man". Andy Green, Out and About, Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Liverpool Pride returns for 2012". Liverpool Pride. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Superheroes theme for Liverpool Pride 2013". Liverpool Echo. 30 March 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- "Liverpool Pride sees 75,000 people join in the fun". Liverpool Echo. 5 August 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "It's Liverpool Pride Waterfront Stage". Liverpool Pride. July 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Stanley St Quarter Stage". Liverpool Pride. July 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "the Lomax: Shout It, Live, Loud & Proud". Liverpool Pride. July 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Liverpool Pride 2012: Countdown begins as festival prepares to set sail". Liverpool Pride. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- "Liverpool Pride festival attracts thousands". BBC Liverpool. 5 August 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- "It's Liverpool Pride Waterfront Stage". Liverpool Pride. July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- "LCH Stanley St Quarter Stage". Liverpool Pride. July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- "Eberle St Stage". Liverpool Pride. July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- "Proud Mersey - Over 40,000 attend Liverpool Pride 2011". Liverpool Pride. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "The Countdown Begins!". Liverpool Pride. 1 August 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- "The Countdown Begins!". Liverpool Pride. 1 August 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- "The Countdown Begins to Liverpool Pride 2011". MusicMafia UK. 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- "First Liverpool Pride sees 21,000 enjoy gay, lesbian and bisexual festival". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Main Stage". Liverpool Pride. 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- "Cabaret Stage". Liverpool Pride. 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- "Acoustic Stage". Liverpool Pride. 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- "Liverpool Pride Move- The full interview". Seen Magazine. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Feasts for the Eyes". Liverpool Pride. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- "Timeline: Gay fight for equal rights". BBC News. 6 December 2002. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- http://www.qrd.org/qrd/world/europe/uk/scotland/pulse/37-09.95

- "Liverpool's journey to Gay Pride". BBC Liverpool. 11 June 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Merseyside Resistance Calendar - June". Nerve Issue 11 (Winter 2007). Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- "Pride London: From gay protest to street party". The Independent. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Liverpool LGBT Pride Festival. |