LGBT parenting

LGBT parenting refers to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people raising one or more children as parents or foster care parents. This includes: children raised by same-sex couples (same-sex parenting), children raised by single LGBT parents, and children raised by an opposite-sex couple where at least one partner is LGBT.

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

| lesbian ∙ gay ∙ bisexual ∙ transgender |

|

|

Opponents of LGBT rights have argued that LGBT parenting adversely affects children. However, scientific research consistently shows that gay and lesbian parents are as fit and capable as heterosexual parents, and their children are as psychologically healthy and well-adjusted as those reared by heterosexual parents.[1][2][3][4][5] Major associations of mental health professionals in the U.S., Canada, and Australia have not identified credible empirical research that suggests otherwise.[5][6][7][8][9]

Forms

LGBT people can become parents through various means including current or former relationships, coparenting, adoption, foster care, donor insemination, reciprocal IVF, and surrogacy.[10][11] A gay man, a lesbian, or a transgender person who transitions later in life may have children within an opposite-sex relationship, such as a mixed-orientation marriage, for various reasons.[12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

Some children do not know they have an LGBT parent; coming out issues vary and some parents may never reveal to their children that they identify as LGBT. Accordingly, how children respond to their LGBT parent(s) coming out has little to do with their sexual orientation or gender identification of choice, but rather with how either parent responds to acts of coming out; i.e. whether there is dissolution of parental partnerships or rather if parents maintain a healthy, open, and communicative relationship after coming out or during transition in the case of trans parents.[19][20][21]

Many lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people are parents. In the 2000 U.S. Census, for example, 33 percent of female same-sex couple households and 22 percent of male same-sex couple households reported at least one child under the age of 18 living in the home.[22] As of 2005, an estimated 270,313 children in the United States live in households headed by same-sex couples.[23]

.JPG.webp)

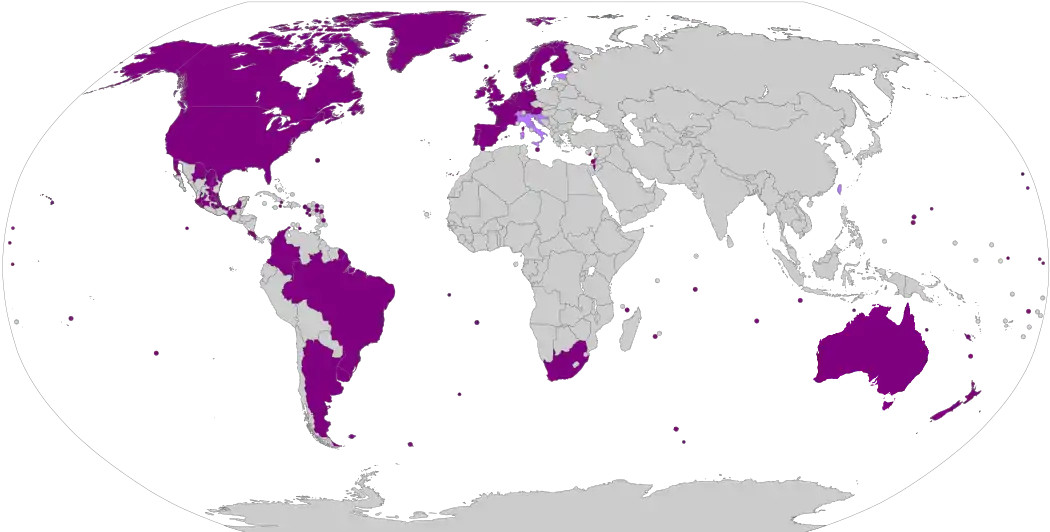

Adoption

Joint adoption by same-sex couples is legal in 27 countries and in some sub-national territories. Furthermore, 5 countries have legalized some form of step-child adoption.

Judgements

In January 2008, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that an otherwise legally qualified and suitable candidate must not be excluded from adopting based on their sexual orientation.[24]

In 2010 a Florida court declared that "reports and studies find that there are no differences in the parenting of homosexuals or the adjustment of their children", therefore the Court is satisfied that the issue is so far beyond dispute that it would be irrational to hold otherwise.[25]

Surrogacy

Some gay couples decide to have a surrogate pregnancy. A surrogate is a woman carrying an egg fertilised by sperm of one of the men. Some women become surrogates for money, others for humanitarian reasons or both.[26] Parents who use surrogacy services can be stigmatised.[27]

Insemination

Insemination is a method used mostly by lesbian couples. It is when a partner is fertilised with donor sperm injected through a syringe. Some men donate sperm for humanitarian reasons, others for money or both. In some countries, the donor can choose to be anonymous (for example in Spain) and in others, they cannot have their identity withheld (United Kingdom).

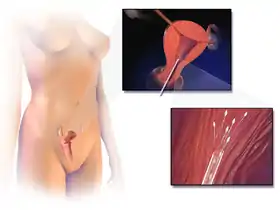

Reciprocal IVF

Reciprocal IVF is used by couples who both possess female reproductive organs. Using in vitro fertilization, eggs are removed from one partner to be used to make embryos that the other partner will hopefully carry in a successful pregnancy.[11]

Statistics

According to U.S. Census Snapshot published in December 2007, same-sex couples with children have significantly fewer economic resources and significantly lower rates of homeownership than heterosexual married couples.[23]

According to a 2013–14 survey conducted in Poland by the Institute of Psychology of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IP PAN) on 3000 LGBT people in same-sex relationships living in the country, 9% (11.7% of women and 4.6% of men) of coupled LGBT people were parents.[30] The 2011 Canadian Census had similar conclusions to these of the Polish study: 9.4% of Canadian gay couples were bringing up children.[31]

Research

| Family law |

|---|

| Family |

Scientific research consistently shows that gay and lesbian parents are as fit and capable as heterosexual parents, and their children are as psychologically healthy and well-adjusted as those reared by heterosexual parents.[1][2][5] Major associations of mental health professionals in the U.S., Canada, and Australia have not identified credible empirical research that suggests otherwise.[5][6][7][8][9]

In the United States, studies on the effect of gay and lesbian parenting on children were first conducted in the 1970s, and expanded through the 1980s in the context of increasing numbers of gay and lesbian parents seeking legal custody of their biological children.[32]

Methodology

Studies of LGBT parenting have sometimes suffered from small and/or non-random samples and inability to implement all possible controls, due to the small LGBT parenting population and to cultural and social obstacles to identifying as an LGBT parent.

A 1993 review published in the Journal of Divorce & Remarriage identified fourteen studies addressing the effects of LGBT parenting on children. The review concluded that all of the studies lacked external validity and that therefore: "The conclusion that there are no significant differences in children reared by lesbian mothers versus heterosexual mothers is not supported by the published research database."[33]

Fitzgerald's 1999 analysis explained some methodological difficulties:

Many of these studies suffer from similar limitations and weaknesses, with the main obstacle being the difficulty in acquiring representative, random samples on a virtually invisible population. Many lesbian and gay parents are not open about their sexual orientation due to real fears of discrimination, homophobia, and threats of losing custody of their children. Those who do participate in this type of research are usually relatively open about their homosexuality and, therefore, may bias the research towards a particular group of gay and lesbian parents.

Because of the inevitable use of convenience samples, sample sizes are usually very small and the majority of the research participants end up looking quite homogeneous—e.g. white, middle-class, urban, and well-educated. Another pattern is the wide discrepancy between the number of studies conducted with children of gay fathers and those with lesbian mothers...

Another potential factor of importance is the possibility of social desirability bias when research subjects respond in ways that present themselves and their families in the most desirable light possible. Such a phenomenon does seem possible due to the desire of this population to offset and reverse negative images and discrimination. Consequently, the findings of these studies may be patterned by self-presentation bias.[32]

According to a 2001 review of 21 studies by Stacey and Biblarz published in American Sociological Review: "[R]esearchers lack reliable data on the number and location of lesbigay parents with children in the general population, there are no studies of child development based on random, representative samples of such families. Most studies rely on small-scale, snowball and convenience samples were drawn primarily from personal and community networks or agencies. Most research to date has been conducted on white lesbian mothers who are comparatively educated, mature, and reside in relatively progressive urban centers, most often in California or the Northeastern states."[34]

In more recent studies,[35] many of these issues have been resolved due to factors such as the changing social climate for LGBT people.

Herek's 2006 paper in American Psychologist stated:

The overall methodological sophistication and quality of studies in this domain have increased over the years, as would be expected for any new area of empirical inquiry. More recent research has reported data from probability and community-based convenience samples, has used more rigorous assessment techniques, and has been published in highly respected and widely cited developmental psychology journals, including Child Development and Developmental Psychology. Data are increasingly available from prospective studies. In addition, whereas early study samples consisted mainly of children originally born into heterosexual relationships that subsequently dissolved when one parent came out as gay or lesbian, recent samples are more likely to include children conceived within a same-sex relationship or adopted in infancy by a same-sex couple. Thus, they are less likely to confound the effects of having a sexual minority parent with the consequences of divorce.[7]

A 2002 review of the literature identified 20 studies examining outcomes among children raised by gay or lesbian parents and found that these children did not systematically differ from those raised by heterosexual parents on any of the studied outcomes.[36]

In a 2009 affidavit filed in the case Gill v. Office of Personnel Management, Michael Lamb, a professor of psychology and head of Department of Social and Developmental Psychology at Cambridge University, stated:

The methodologies used in the major studies of same-sex parenting meet the standards for research in the field of developmental psychology and psychology generally. The studies specific to same-sex parenting were published in leading journals in the field of child and adolescent development, such as Child Development, published by the Society for Research in Child Development, Developmental Psychology, published by the American Psychological Association, and The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, the flagship peer-review journals in the field of child development. Most of the studies appeared in these (or similar) rigorously peer-reviewed and highly selective journals, whose standards represent expert consensus on generally accepted social scientific standards for research on child and adolescent development. Prior to publication in these journals, these studies were required to go through a rigorous peer-review process, and as a result, they constitute the type of research that members of the respective professions consider reliable. The body of research on same-sex families is consistent with standards in the relevant fields and produces reliable conclusions."[37]

Gartrell and Bos's 25-year longitudinal study, published 2010, was limited to mothers who sought donor insemination and who may have been more motivated than mothers in other circumstances.[38] Gartrell and Bos note that the study's limitations included utilizing a non-random sample, and the lesbian group and control group were not matched for race or area of residence. The study was supported by grants from the Gill Foundation, the Lesbian Health Fund of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, Horizons Foundation, and the Roy Scrivner Fund of the American Psychological Foundation.[39]

Michael J. Rosenfeld, associate professor of sociology at Stanford University, wrote in a 2010 study published in Demography that "[A] critique of the literature—that the sample sizes of the studies are too small to allow for statistically powerful tests—continues to be relevant." Rosenfeld's study, "the first to use large-sample nationally representative data," found that children of same-sex couples demonstrated normal outcomes in school. "The core finding here," reports the study," offers a measure of validation for the prior, and much-debated, small-sample studies."[40]

According to a 2005 brief by the American Psychological Association:

In summary, research on diversity among families with lesbian and gay parents and on the potential effects of such diversity on children is still sparse (Martin, 1993, 1998; Patterson, 1995b, 2000, 2001, 2004; Perrin, 2002; Stacey & Biblarz, 2001; Tasker, 1999). Data on children of parents who identify as bisexual are still not available, and information about children of non-White lesbian or gay parents is hard to find (but see Wainright et al., 2004, for a racially diverse sample)... However, the existing data are still limited, and any conclusions must be seen as tentative... It should be acknowledged that research on lesbian and gay parents and their children, though no longer new, is still limited in extent. Although studies of gay fathers and their children have been conducted (Patterson, 2004), less is known about children of gay fathers than about children of lesbian mothers. Although studies of adolescent and young adult offspring of lesbian and gay parents are available (e.g., Gershon et al., 1999; Tasker & Golombok, 1997; Wainright et al., 2004), relatively few studies have focused on the offspring of lesbian or gay parents during adolescence or adulthood.[41]

In 2010 American Psychological Association, The California Psychological Association, The American Psychiatric Association, and the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy stated:

Relatively few studies have directly examined gay fathers, but those that exist find that gay men are similarly fit and able parents, as compared to heterosexual men. Available empirical data do not provide a basis for assuming gay men are unsuited for parenthood. If gay parents were inherently unfit, even small studies with convenience samples would readily detect it. This has not been the case. Being raised by a single father does not appear to inherently disadvantage children's psychological wellbeing more than being raised by a single mother. Homosexuality does not constitute a pathology or deficit, and there is no theoretical reason to expect gay fathers to cause harm to their children. Thus, although more research is needed, available data place the burden of empirical proof on those who argue that having a gay father is harmful.[5]

A significant increase in methodological rigor was achieved in a 2020 study by Deni Mazrekaj at University of Oxford, Kristof De Witte and Sofie Cabus at KU Leuven published in the American Sociological Review.[35] The authors used administrative longitudinal data on the entire population of children born between 1998 and 2007 in the Netherlands, which was the first country to legalize same-sex marriage. They followed the educational performance of 2,971 children with same-sex parents and over a million children with different-sex parents from birth. This was the first study to address how children who were actually raised by same-sex parents from birth (instead of happening to live with a same-sex couple at some point in time) perform in school while retaining a large representative sample. The authors found that children raised by same-sex parents from birth perform better than children raised by different-sex parents in both primary and secondary education. According to the authors, a major factor explaining these results was parental socioeconomic status. Same-sex couples often have to use expensive fertility treatments and adoption procedures to have a child, meaning they tend to be wealthier, older and more educated than the typical different-sex couple.

Consensus

Scientific research that has directly compared outcomes for children with gay and lesbian parents with outcomes for children with heterosexual parents has found that children raised by same-sex couples are as physically or psychologically healthy, capable, and successful as those raised by opposite-sex couples,[1][2][5] despite the reality that considerable legal discrimination and inequity remain significant challenges for these families.[2] Major associations of mental health professionals in the U.S., Canada, and Australia, have not identified credible empirical research that suggests otherwise.[5][6][7][8][9] Sociologist Wendy Manning echoes their conclusion that "[The] studies reveal that children raised in same-sex parent families fare just as well as children raised in different-sex parent families across a wide spectrum of child well-being measures: academic performance, cognitive development, social development, psychological health, early sexual activity, and substance abuse."[42] The range of these studies allows for conclusions to be drawn beyond any narrow spectrum of a child's well-being, and the literature further indicates that parents' financial, psychological and physical well-being is enhanced by marriage and that children benefit from being raised by two parents within a legally recognized union.[5][6][37][43] There is evidence that nuclear families with homosexual parents are more egalitarian in their distribution of home and childcare activities, and thus less likely to embrace traditional gender roles.[44] Nonetheless, the American Academy of Pediatrics reports that there are no differences in the interests and hobbies between children with homosexual versus heterosexual parents.[45]

Since the 1970s, it has become increasingly clear that it is family processes (such as the quality of parenting, the psychosocial well-being of parents, the quality of and satisfaction with relationships within the family, and the level of co-operation and harmony between parents) that contribute to determining children's well-being and outcomes rather than family structures, per se, such as the number, gender, sexuality and cohabitation status of parents.[2][37] Since the end of the 1980s, as a result, it has been well established that children and adolescents can be as well-adjusted in nontraditional settings as in traditional settings.[37] Furthermore, whereas factors such as the number and cohabitation status of parents can and do influence relationship quality in aggregate, the same has not been demonstrated for sexuality. According to sociologist Judith Stacey of New York University, "Rarely is there as much consensus in any area of social science as in the case of gay parenting, which is why the American Academy of Pediatrics and all of the major professional organizations with expertise in child welfare have issued reports and resolutions in support of gay and lesbian parental rights".[46] These organizations include the American Academy of Pediatrics,[6] the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,[47] the American Psychiatric Association,[48] the American Psychological Association,[49] the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy,[50] the American Psychoanalytic Association,[51] the National Association of Social Workers,[52] the Child Welfare League of America,[53] the North American Council on Adoptable Children,[54] and Canadian Psychological Association.[55] In 2006, Gregory M. Herek stated in American Psychologist: "If gay, lesbian, or bisexual parents were inherently less capable than otherwise comparable heterosexual parents, their children would evidence problems regardless of the type of sample. This pattern clearly has not been observed. Given the consistent failures in this research literature to disprove the null hypothesis, the burden of empirical proof is on those who argue that the children of sexual minority parents fare worse than the children of heterosexual parents."[7]

Studies and analyses include Bridget Fitzgerald's 1999 analysis of the research on gay and lesbian parenting, published in Marriage and Family Review, which found that the available studies generally concluded that "the sexual orientation of parents is not an effective or important predictor of successful childhood development"[32] and Gregory M. Herek's 2006 analysis in American Psychologist, which said: "Despite considerable variation in the quality of their samples, research design, measurement methods, and data analysis techniques, the findings to date have been remarkably consistent. Empirical studies comparing children raised by sexual minority parents with those raised by otherwise comparable heterosexual parents have not found reliable disparities in mental health or social adjustment. Differences have not been found in parenting ability between lesbian mothers and heterosexual mothers. Studies examining gay fathers are fewer in number but do not show that gay men are any less fit or able as parents than heterosexual men."[7] Additionally, some fear that children will inherit their parent's gender dysphoria or alternate mental health issues in the case of trans parent, yet there is research that suggests "an absence of evidence that children raised by transgendered parents have a greater chance of experiencing […] development issues than raised by non-transgender parents" and further clinical research shows that "children of gender-variant parents do not develop gender dysphoria or mental diseases" due to their parents' diagnosis with gender identity disorder [21] A 1996 meta-analysis found "no differences on any measures between the heterosexual and homosexual parents regarding parenting styles, emotional adjustment, and sexual orientation of the child(ren)";[56] and a 2008 meta-analysis reached similar conclusions.[57]

In June 2010, the results of a 25-year ongoing longitudinal study by Nanette Gartrell of the University of California and Henny Bos of the University of Amsterdam were released. Gartrell and Bos studied 78 children conceived through donor insemination and raised by lesbian mothers. Mothers were interviewed and given clinical questionnaires during pregnancy and when their children were 2, 5, 10, and 17 years of age. In the abstract of the report, the authors stated: "According to their mothers' reports, the 17-year-old daughters and sons of lesbian mothers were rated significantly higher in social, school/academic, and total competence and significantly lower in social problems, rule-breaking, aggressive, and externalizing problem behavior than their age-matched counterparts in Achenbach's normative sample of American youth."[39]

Analysis of extensive social science literature into the question of children's psychological outcomes of being raised by same-sex parents by the Australian Institute of Family Studies in 2013 concluded that "there is now strong evidence that same-sex parented families constitute supportive environments in which to raise children" and that with regard to lesbian parenting "...clear benefits appear to exist with regard to: the quality of parenting children experience in comparison to their peers parented in heterosexual couple families; children's and young adults' greater tolerance of sexual and gender diversity; and gender flexibility displayed by children, particularly sons."[58]

Sexual orientation and gender role

Reviews of data from studies thus far suggest that children reared by non-heterosexual parents have outcomes similar to those of children reared by heterosexual parents with respect to sexual orientation.[59] According to the U.S. Census, 80% of the children being raised by same-sex couples in the United States are their biological children.[60] Regarding biological children of non-heterosexuals, a 2016 review lead by J. Michael Bailey states "We would expect, for example, that homosexual parents should be more likely than heterosexual parents to have homosexual children on the basis of genetics alone", since there is some genetic contribution to sexual orientation, and parents and children share 50 percent of their genes.[59]

Important observations from research on twins separated at birth and large adoption studies, is that parents tend to have little to no environmental effects on their children's behavioural traits, which are instead correlated with genes shared between parent and child and the non-shared environment (environment which is unique to the child, such as random developmental noise and events, as opposed to rearing).[59] The 2016 Bailey et al. review concludes that there "is good evidence for both genetic and nonsocial environmental influences on sexual orientation" including prenatal developmental events, but that there is better evidence for biological mechanisms relating to male sexual orientation, which appears unresponsive to socialization, saying "we would be surprised if differences in social environment contributed to differences in male sexual orientation at all."[59]:87 In contrast, they say that female sexual orientation may be somewhat responsive to social environment, saying "it would also be less surprising to us to discover that social environment affects female sexual orientation and related behavior, that possibility must be scientifically supported rather than assumed."[59]:87

A 2013 statement from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry states that children of LGBT parents do not have any differences in their gender role behaviors in comparison to those observed in heterosexual family structures.[61]

A 2005 review by Charlotte J. Patterson for the American Psychological Association found that the available data did not suggest higher rates of homosexuality among the children of lesbian or gay parents.[41] Herek's 2006 review describes the available data on the point as limited.[7] Stacey and Biblarz and Herek stress that the sexual orientation and gender identification of children is of limited relevance to discussions of parental fitness or policies based on the same. In a 2010 review comparing single-father families with other family types, Stacey and Biblarz state, "We know very little yet about how parents influence the development of their children's sexual identities or how these intersect with gender."[62] When it comes to family socialization processes and "contextual effects," Stacey and Biblarz say that children with such parents are more likely to grow up in relatively more tolerant school, neighborhood, and social contexts.[34]

Social challenges and support systems

.jpg.webp)

Children may struggle with negative attitudes about their parents from the harassment they may encounter by living in society.[63] There are many risks and challenges that can occur for children of LGBT families and their parents in North America, including those in the individual domain, family domain, and community/school domain.[64] Hegemonic social norms can lead some children to struggle in all or several domains.[65] Social interactions at school, extracurricular activities, and religious organizations can promote negative attitudes towards their parents and themselves based on gender and sexuality.[65] Bias, stereotypes, micro-aggressions, harm, and violence that both students and parents can often encounter are a result of identifying outside of social normative, cis-gendered, heterosexual society or having their identity used as a weapon against them.[66][67]

The forms of harm and violence that LGBT young people can experience include physical harm and harassment, cyber harassment, assault, bullying, micro-aggressions and beyond. Due to the increased risk of harm experienced, children of LGBT parents and LGBT students can also experience increased levels of stress, anxiety, and self-esteem issues.[68][66] Several legal and social protections support children and parents who experience transphobia and homophobia in the community, school, and family.[69] Practicing and developing supportive networks within schools and working towards resilience skills can assist in creating safe environments for students and parents.[69] Social supports, ally development, and positive school environments are direct ways to challenge homophobia and transphobia directed at these students and their families. Several networks and school clubs can be set up and led by student youth to create positive school environments and community environments for LGBT students and their families.[64] Organizations such as Gay-Straight Alliance Network (GSA), American Civil Liberties Union(ACLU), and Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) can assist in supportive school environments. Community resources for LGBT children and parents such as the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), The Trevor Project, and Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) can assist in building personal support systems.[70][65]

Other

Stephen Hicks, a reader in health and social care at the University of Salford[71] questions the value of trying to establish that lesbian or gay parents are defective or suitable. He argues such positions are flawed because they are informed by ideologies that either oppose or support such families.[72] In Hicks' view:

Instead of asking whether gay parenting is bad for kids, I think we should ask how contemporary discourses of sexuality maintain the very idea that lesbian and gay families are essentially different and, indeed, deficient. But, in order to ask this, I think that we need a wider range of research into lesbian and gay parenting... More work of this sort will help us to ask more complex questions about forms of parenting that continue to offer some novel and challenging approaches to family life.[72]

Misrepresentation by opponents

In a 2006 statement, the Canadian Psychological Association released an updated statement on their 2003 and 2005 conclusions, saying, "The CPA recognizes and appreciates that persons and institutions are entitled to their opinions and positions on this issue. However, CPA is concerned that some persons and institutions are misinterpreting the findings of psychological research to support their positions when their positions are more accurately based on other systems of belief or values."[1] Several professional organizations have noted that studies which opponents of LGBT parenting claim as evidence that same-sex couples are unfit parents do not in fact address same-sex parenting, however, and therefore do not permit any conclusions to be drawn about the effects of the sexes or sexual orientations of parents. Rather, these studies, which only sampled heterosexual parents, found that it was better for children to be raised by two parents instead of one, and/or that the divorce or death of a parent had a negative effect on children.[1][73] In Perry v. Brown, in which Judge Vaughn Walker found that the available studies on stepchildren, which opponents of same-sex marriage cited to support their position that it is best for a child to be raised by its biological mother and father, do not isolate "the genetic relationship between a parent and a child as a variable to be tested" and only compare "children raised by married, biological parents with children raised by single parents, unmarried mothers, step families and cohabiting parents," and thus "compare various family structures and do not emphasize biology."[74] Perry also cited studies showing that "adopted children or children conceived using sperm or egg donors are just as likely to be well-adjusted as children raised by their biological parents."[74]

Gregory M. Herek noted in 2006 that "empirical research can't reconcile disputes about core values, but it is very good at addressing questions of fact. Policy debates will be impoverished if this important source of knowledge is simply dismissed as a 'he said, she said' squabble."[75]

Other aspects

Marriage

Same-sex parenting is often raised as an issue in debates about the recognition of same-sex marriage by law.

Trans parenting

There is little to no visibility or public support through pregnancy and parenting resources directed towards trans parents.[21][76]

While "once gay and lesbian parents attain parenthood status[…] they almost never lose it" this is not the case for trans parents, as seen with the cases of Suzanne Daly (1983) and Martha Boyd (2007), two trans women who both had their parental rights, with regard to biological children, terminated on the basis of their diagnosis of gender identity disorder and their trans status.[77] They were perceived to have abandoned their role as "fathers" through their MTF transition, and were perceived to have acted selfishly in putting their own sexual/identity needs before the wellbeing of their children. These cases are amongst many legal custody battles fought by trans parents whereby U.S. courts have completely overlooked defendants' suitability as "parents" as opposed to "mothers" or "fathers," roles that are heavily gendered and come with strict societal understandings of normative parental behaviour.[78] In the case of trans individuals who desire to become parents and to be legally recognized as mothers or fathers of their children, courts often refuse to legally acknowledge such roles because of biological discrimination. An example of this is the X, Y and Z vs. U.K case, whereby X, a trans man who had been in a stable relationship with Y, a biological woman who gave birth to Z through artificial insemination through which X was always present, was denied the right to be listed as Z's father on their birth certificate due to the fact that they did not directly inseminate Y.[79]

Recently, Canada has started acknowledging trans parental rights in terms of custody arrangements and of legal recognition of parental status. In 2001, Leslie (formerly Howard) Forester was permitted to retain custody of her daughter after her ex-partner filed for sole custody on the basis of Leslie's transition. The courts ruled that "the applicant's transsexuality, in itself, without further evidence, would not constitute a material change in circumstances, nor would it be considered a negative factor in a custody determination," marking a landmark case in family law whereby "a person's transsexuality is irrelevant on its own as a factor in his or her ability to be a good parent"[80] Additionally, Jay Wallace, a resident trans-man from Toronto, Canada, "was permitted to identify as Stanley's father on the province of Ontario's Statement of Live Birth Form," marking a decoupling of genetics and bio-sex in relation to parental roles.[81]

See also

Social

- Coparenting

- LGBT adoption

- LGBT adoption in Europe

- LGBT youth vulnerability

- Marriage promotion

- Same-sex marriage and the family

- Surrogacy

- Third party reproduction

Medical:

Research:

- New Family Structures Study: Published by Mark Regnerus in 2012, this study was widely discredited by researchers, and which claimed to show that children of gay and lesbian parents were adversely affected by their upbringing by parents in same-sex relationships.[82]

- Homosexual parenting in animals

Regional:

References

- "Marriage of Same-Sex Couples – 2006 Position Statement Canadian Psychological Association" (PDF). 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-04-19.

- "Elizabeth Short, Damien W. Riggs, Amaryll Perlesz, Rhonda Brown, Graeme Kane: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Parented Families – A Literature Review prepared for The Australian Psychological Society" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-01-15.

- Manning, Wendy D.; Fettro, Marshal Neal; Lamidi, Esther (2014-08-01). "Child Well-Being in Same-Sex Parent Families: Review of Research Prepared for American Sociological Association Amicus Brief". Population research and policy review. 33 (4): 485–502. doi:10.1007/s11113-014-9329-6. ISSN 0167-5923. PMC 4091994. PMID 25018575.

- "What does the scholarly research say about the well-being of children with gay or lesbian parents?" (PDF). December 2017.

- "Brief of the American Psychological Association, Kentucky Psychological Association, Ohio Psychological Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy, Michigan Association for Marriage and Family Therapy, National Association of Social Workers, National Association of Social Workers Tennessee Chapter, National Association of Social Workers Michigan Chapter, National Association of Social Workers Kentucky Chapter, National Association of Social Workers Ohio Chapter, American Psychoanalytic Association, American Academy of Family Physicians, and American Medical Association as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2017-06-27.

- Pawelski JG, Perrin EC, Foy JM, et al. (July 2006). "The effects of marriage, civil union, and domestic partnership laws on the health and well-being of children". Pediatrics. 118 (1): 349–64. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1279. PMID 16818585.

- Herek, Gregory M. (2006). "Legal recognition of same-sex relationships in the United States: A social science perspective" (PDF). American Psychologist. 61 (6): 607–621. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.6.607. PMID 16953748. S2CID 6669364.

- Biblarz, Timothy J.; Stacey, Judith (February 2010). "How Does the Gender of Parents Matter?". Journal of Marriage and Family. 72 (1): 3–22. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.593.4963. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00678.x.

- "Brief presented to the Legislative House of Commons Committee on Bill C38 by the Canadian Psychological Association – June 2, 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- Berkowitz, D & Marsiglio, W (2007). Gay Men: Negotiating Procreative, Father, and Family Identities. Journal of Marriage and Family 69 (May 2007): 366–381

- Bodri, D.; Nair, S.; Gill, A.; Lamanna, G.; Rahmati, M.; Arian-Schad, M.; Smith, V.; Linara, E.; Wang, J.; Macklon, N.; Ahuja, K.K. (February 2018). "Shared motherhood IVF: high delivery rates in a large study of treatments for lesbian couples using partner-donated eggs". Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 36 (2): 130–136. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.11.006. PMID 29269265.

- Butler, Katy (March 7, 2006). "Many Couples Must Negotiate Terms of 'Brokeback' Marriages". New York Times.

- "Gay Men from Heterosexual Marriages: Attitudes, Behaviors, Childhood Experiences, and Reasons for Marriage". Haworth Press. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Stack, Peggy Fletcher (August 5, 2006), "Gay, Mormon, married", The Salt Lake Tribune, archived from the original on June 21, 2013, retrieved September 12, 2013

- Moore, Carrie A. (March 30, 2007). "Gay LDS men detail challenges". Deseret Morning News.

- Bozett, Frederick W. (1987). "The Heterosexually Married Gay and Lesbian Parent". Gay and Lesbian Parents. New York: Praeger. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-275-92541-3.

- Büntzly G (1993). "Gay fathers in straight marriages". Journal of Homosexuality. 24 (3–4): 107–14. doi:10.1300/J082v24n03_07. PMID 8505530.

- "The Married Lesbian". Haworth Press. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Dunne EJ (1987). "Helping gay fathers come out to their children". Journal of Homosexuality. 14 (1–2): 213–22. doi:10.1300/J082v14n01_16. PMID 3655343.

- "A Family Matter: When a Spouse Comes Out as Gay, Lesbian, or Bisexual". Haworth Press. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Faccio, Elena; Bordin, Elena; Cipolletta, Sabrina (October 2013). "Transsexual parenthood and new role assumptions". Culture, Health & Sexuality. 15 (9): 1055–1070. doi:10.1080/13691058.2013.806676. PMID 23822798. S2CID 32472958.

- APA Policy Statement on Sexual Orientation, Parents & Children, American Psychological Association, July 28 & 30, 2004. Retrieved on 04-06-2007.

- Williams Institute: Census Snapshot – United States Archived 2008-02-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Judgment in the case of E.B. v. France

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-10-10. Retrieved 2010-09-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "For Gay Men: Becoming a Parent through Surrogacy". Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Gahan, Luke (2017) "Separated Same-Sex Parents' Experiences and Views of Services and Service Providers," Journal of Family Strengths: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol17/iss2/2

- "Breakthrough raises possibility of genetic children for same-sex couples". Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- "Stem Cells and Same Sex Reproduction". Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Joanna Mizielińska, Marta Abramowicz, Agata Stasińska (2014). "Rodziny z wyboru w Polsce. Życie rodzinne osób nieheteroseksualnyc" (PDF). rodzinyzwyboru.pl. Retrieved 11 March 2018.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/98-312-x/98-312-x2011001-eng.pdf

- Fitzgerald, Bridget (November 1999). "Children of Lesbian and Gay Parents: A Review of the Literature". Marriage & Family Review. 29 (1): 57–75. doi:10.1300/J002v29n01_05.

- Belcastro, Philip A.; Gramlich, Theresa; Nicholson, Thomas; Price, Jimmie; Wilson, Richard (7 March 1994). "A Review of Data Based Studies Addressing the Affects of Homosexual Parenting on Children's Sexual and Social Functioning". Journal of Divorce & Remarriage. 20 (1–2): 105–122. doi:10.1300/J087v20n01_06.

- Stacey, Judith; Biblarz, Timothy J. (April 2001). "(How) Does the Sexual Orientation of Parents Matter?" (PDF). American Sociological Review. 66 (2): 159. doi:10.2307/2657413. JSTOR 2657413. S2CID 36206795.

If these young adults raised by lesbian mothers were more open to a broad range of sexual possibilities, they were not statistically more likely to self-identify as bisexual, lesbian, or gay.....Children raised by lesbian co-parents should and do seem to grow up more open to homoerotic relationships. This may be partly due to genetic and family socialization processes, but what sociologists refer to as "contextual effects" not yet investigated by psychologists may also be important...even though children of lesbian and gay parents appear to express a significant increase in homoeroticism, the majority of all children nonetheless identify as heterosexual, as most theories across the essentialistt" to "social constructionist" spectrum seem (perhaps too hastily) to expect.

- Mazrekaj, Deni; De Witte, Kristof; Cabus, Sofie (2020). "School Outcomes of Children Raised by Same-Sex Parents: Evidence from Administrative Panel Data". American Sociological Review. 85 (5): 830–856. doi:10.1177/0003122420957249. S2CID 222002953.

- Anderssen, Norman; Amlie, Christine; Ytterøy, Erling André (September 2002). "Outcomes for children with lesbian or gay parents. A review of studies from 1978 to 2000". Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 43 (4): 335–351. doi:10.1111/1467-9450.00302. PMID 12361102.

- Michael Lamb, Affidavit – United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts (2009) Archived 2010-12-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Discover magazine "Same-Sex Parents Do No Harm". January 2, 2011 edition, p. 77

- Gartrell N, Bos H (2010). "US National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study: Psychological Adjustment of 17-Year-Old Adolescents". Pediatrics. 126 (1): 28–36. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-3153. PMID 20530080.

- Rosenfeld, Michael J. (2010). "Nontraditional Families and Childhood Progress Through School". Demography. 47 (3): 755–775. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0112. PMC 3000058. PMID 20879687.

- American Psychological Association Lesbian & Gay Parenting

- Manning, Wendy D., Marshal Neal Fettro, and Esther Lamidi. "Child well-being in same-sex parent families: Review of research prepared for American Sociological Association Amicus Brief." Population research and policy review 33.4 (2014): 485-502.Child Well-Being in Same-Sex parent families,

- Canadian Psychological Association: Marriage of Same-Sex Couples – 2006 Position Statement Canadian Psychological Association

- Escobar, Samantha (July 27, 2013). "Children of Gay Couples Impacted By Parents' Relationship But Not Sexual Orientation: Study". Huffington Post. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- "Gay and Lesbian Parents". American Academy Of Pediatrics. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- cited in Cooper & Cates, 2006, p. 36; citation available on http://www.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/LGBT-Families-Lit-Review.pdf

- Children with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Parents Archived 2010-06-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Adoption and Co-parenting of Children by Same-sex Couples (archived from )

- Sexual Orientation, Parents, & Children

- Archived September 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Position Statement on Gay and Lesbian Parenting Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Case No. S147999 in the Supreme Court of the State of California, In re Marriage Cases Judicial Council Coordination Proceeding No. 4365, Application for leave to file brief amici curiae in support of the parties challenging the marriage exclusion, and brief amici curiae of the American Psychological Association, California Psychological Association, American Psychiatric Association, National Association of Social Workers, and National Association of Social Workers, California Chapter in support of the parties challenging the marriage exclusion

- Position Statement on Parenting of Children by Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adults Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine

- "NACAC - Public Policy". Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- "Canadian Psychological Association" (PDF). Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Allen, M; Burrell, N (1996). "Comparing the impact of homosexual and heterosexual parents on children: meta-analysis of existing research". Journal of Homosexuality. 32 (2): 19–35. doi:10.1300/j082v32n02_02. PMID 9010824.

- Crowl, Alicia; Ahn, Soyeon; Baker, Jean (12 August 2008). "A Meta-Analysis of Developmental Outcomes for Children of Same-Sex and Heterosexual Parents". Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 4 (3): 385–407. doi:10.1080/15504280802177615. S2CID 24069055.

- Dempsey, Deborah (Dr) (2013). "Same-sex parented families in Australia" (PDF). CFCA Paper. 18 (1): 19.

- Bailey, J. Michael; Vasey, Paul L.; Diamond, Lisa M.; Breedlove, S. Marc; Vilain, Eric; Epprecht, Marc (2016). "Sexual Orientation, Controversy, and Science". Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 17 (2): 84–86. doi:10.1177/1529100616637616. PMID 27113562.

- DONALDSON JAMES, SUSAN (June 23, 2011). "Census 2010: One-Quarter of Gay Couples Raising Children". ABC News. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

Still, more than 80 percent of the children being raised by gay couples are not adopted, according to Gates.

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (August 2013). "Children with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Parents" (PDF). Facts for Families. No. 92. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- Biblarz, Timothy J.; Stacey, Judith (February 2010). "How Does the Gender of Parents Matter?". Journal of Marriage and Family. 72 (1): 3–22. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.593.4963. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00678.x.

- Goldberg, Abbie E. (2010). Lesbian and Gay Parents and Their Children. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-4338-0536-3.

- Komosa-Hawkins, Karen; Schanding Jr., G. Thomas (2013). "Promoting resilience in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth". In Fisher, Emily S. (ed.). Creating safe and supportive learning environments a guide for working with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth, and families. New York: Routledge. pp. 41–56. ISBN 978-0-415-89611-5. OCLC 867820951.

- Fisher, Emily S. (2013). Creating Safe and Supportive Learning Environments : A guide for Working with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questions Youth and Families. New York, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-89611-5.

- Emano, Dennis M.; Schanding Jr., G. Thomas (2013). "Counseling lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning students". In Fisher, Emily S.; Komosa-Hawkins, Karen (eds.). Creating safe and supportive learning environments a guide for working with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth, and families. New York: Routledge. pp. 189–208. ISBN 978-0-415-89611-5. OCLC 867820951

- Johnson, Allen G. “The Social Construction of Difference.” Readings for Diversity and Social Justice, edited by Maurianne Adams et al., 4th ed., Routledge, 2018, pp. 16–21.

- Nadal, Kevin L. “Sexual Orientation Microaggresssions: Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual People.” That’s So Gay! Microaggressions and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Community, American Psychological Association, 2013, pp. 51–80

- Espelage, Dorothy L., and Mrinalini A. Rao. “Safe Schools: Prevention and Intervention for Bullying and Harassment.” Creating Safe and Supportive Learning Environments: A Guide for Working with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Youth and Families, edited by Emily S. Fisher and Karen Komoso-Hawkins, Routledge, 2013, pp. 140–54.

- Kennedy, Kelly S. “Accessing Community Resources.” Creating Safe and Supportive Learning Environments: A Guide for Working with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Youth and Families, edited by Emily S. Fisher and Karen Komoso-Hawkins, Routledge, 2013, pp. 243–55.

- Salford University: Alphabetical Staff Listing, accessed June 16, 2011

- Hicks, Stephen (2005). "Is Gay Parenting Bad for Kids? Responding to the 'Very Idea of Difference' in Research on Lesbian and Gay Parents". Sexualities. 8 (2): 165. doi:10.1177/1363460705050852. S2CID 145503185.

- Case No. S147999 in the Supreme Court of the State of California, In re Marriage Cases Judicial Council Coordination Proceeding No. 4365, Application for leave to file brief amici curiae in support of the parties challenging the marriage exclusion, and brief amici curiae of the American Psychological Association, California Psychological Association, American Psychiatric Association, National Association of Social Workers, and National Association of Social Workers, California Chapter in support of the parties challenging the marriage exclusion. Date (see page 49): September 26, 2007

- Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, Ruling in Perry v. Brown Archived 2013-03-16 at the Wayback Machine, accessed May 31, 2012

- LA Times on Lesbian/Gay Parents: He Said/She Said? date:2006/11/03

- Wallace, J. "The Manly Art of Pregnancy," in Bornstein, Kate, and Bergman, S. Bear (2010). Gender Outlaws: The Next Generation. Berkeley: Seal Press

- Donelson, Raff (2020). "Commentary on Daly v. Daly". Feminist Judgments: Family Law Opinions Rewritten. Feminist Judgments: Family Law Opinions Rewritten. pp. 162–186. doi:10.1017/9781108556989.008. ISBN 9781108556989. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- Ball, Carlos A. (2012). The Right to Be Parents: LGBT families and the transformation of parenthood. New York: New York University Press.

- European Court of Human Rights (1997). Case of X, Y and Z v. The United Kingdom, Judgment, retrieved from: http://www.globalhealthrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/ECtHR-1997-X-Y-and-Z-v-United-Kingdom.pdf

- Owens, Anne Marie (2 February 2001). "Father's Sex Change Does Not Alter Custody, Court Says: Girl, 6, Calls Mommy and Daddy; Cautious in Public". The National Post. ProQuest 329903587.

- Karaian, Lara (June 2013). "Pregnant Men: Repronormativity, Critical Trans Theory and the Re(conceive)ing of Sex and Pregnancy in Law". Social & Legal Studies. 22 (2): 211–230. doi:10.1177/0964663912474862. S2CID 145257751.

- Eckholm, Erik (2014-03-21). "Federal Judge Strikes Down Michigan's Ban on Same-Sex Marriage". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2014-08-04. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

Further reading

- Goodfellow, Aaron (2015). Gay Fathers, Their Children, and the Making of Kinship. New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 9780823266036. OCLC 892895171.

- Hérault, Laurence, ed. (2014). La parenté transgenre. Aix-en-Provence: Presses universitaires de Provence. ISBN 9782853999328. OCLC 881703694.

- Mazrekaj, Deni; De Witte, Kristof; Cabus, Sofie (2020). "School Outcomes of Children Raised by Same-Sex Parents: Evidence from Administrative Panel Data". American Sociological Review. 85 (5): 830–856. doi:10.1177/0003122420957249.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LGBT parenting. |

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Parented Families – A Literature Review prepared for The Australian Psychological Society (2007)

- Too High a Price – The Case Against Restricting Gay Parenting (updated second edition) (2006), a publication by the ACLU, includes a detailed review of studies and research.

- American Psychological Association (APA) Public Interest Directorate: Research Summary on Lesbian and Gay Parenting (2005)

- Brief presented to the Legislative House of Commons Committee on Bill C38 By the Canadian Psychological Association (2005)

- Lesbian and Gay Parents and Their Children: Research on the Family Life Cycle