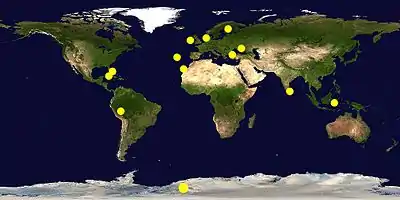

Location hypotheses of Atlantis

Location hypotheses of Atlantis are various proposed real-world settings for the fictional island of Atlantis, described as a lost civilization mentioned in Plato's dialogues Timaeus and Critias, written about 360 B.C. In these dialogues, a character named Critias claims that an island called Atlantis was swallowed by the sea about 9,200 years previously. According to the dialogues, this story was passed down to him through his grandfather, also named Critias, who heard it from his own father, Dropides, who had received it from Solon, the famous Athenian lawmaker, who heard the story from an Egyptian sanctuary. Plato's dialogues locate the island in the Atlantic Pelagos "Atlantic Sea",[2] "in front of" the Pillars of Hercules (Στήλες του Ηρακλή) and facing a district called modern Gades or Gadira (Gadiron), a location that some modern Atlantis researchers associate with modern Gibraltar; however various locations have been proposed.

North-West of Egypt: From Greece to Spain

Most theories of the placement of Atlantis center on the Mediterranean, influenced largely by the geographical location of Egypt from which the story allegedly is derived.

Island of Pharos

Robert Graves in his The Greek Myths (1955), argues Atlantis was the Island of Pharos off the western coast of the Nile Delta, that is, before Alexander the Great connected the island to mainland Egypt by building a causeway.[3]

Knossos and Thera (Santorini)

The Minoan civilization on Crete was the dominant sea power of the eastern Mediterranean, with large cities and temples, but after 1400 BC only small villages existed. Archaeologists believe that some abrupt event changed society, but an invasion is unlikely because of the Minoan fleet.[4] After the discovery of the Minoans at Knossos on the island by Sir Arthur Evans in 1900, theories linking the disappearance of the empire with the destruction of Atlantis were proposed by K. T. Frost in 1913 and E. S. Balch in 1917. This theory was revived by Spyridon Marinatos in 1950, Angelos Galanopoulos in 1960,[5][4] and P. B. S. Andrews in 1967.[6] Galanopoulos argued that Plato's dating of 9,000 years before Solon (said by Plato to have translated Egyptian records of Atlantis)'s time was the result of an error in translation, probably from Egyptian into Greek, which produced "thousands" instead of "hundreds". Such an error would also rescale Plato's Atlantis to the size of Crete, while leaving the city the size of the crater on Thera; 900 years before Solon would be the fifteenth century BC.[4][7] More recent archaeological, seismological, and vulcanological evidence[8][9][10] has expanded the asserted connection of Crete, the island of Santorini, and the Minoan civilization with Plato's description of Atlantis. (Recent arguments for Akrotiri being Atlantis have been popularized on television in shows such as The History Channel show Lost Worlds episode "Atlantis".[11][12]) Evidence said to advance this idea includes:

- The Minoan palace and buildings discovered at the digs at Knossos on Crete and at Akrotiri on the island of Thera have revealed that the Minoans possessed advanced engineering knowledge enabling the construction of three- and four-story buildings with intricate water piping systems, advanced air-flow management, and earthquake-resistant wood and masonry walls. This level of technology was, it is said, far ahead of that found on mainland Greece at the time.

- There are no classical records of an Atlantis-related volcanic eruption in the eastern Mediterranean so it must have occurred before the development of writing, perhaps before 1000 BC.[4] Thera (also called Santorini) is the site of a massive volcanic caldera with an island at its center. Vulcanologists have determined that the island was engulfed by a volcanic eruption around 1600 BC. The event, referred to as the Minoan eruption, was among the most powerful eruptions occurring in the history of civilization, ejecting approximately 60 km³ of material, leaving a layer of pumice and ash 10 to 80 meters thick for 20 to 30 km in all directions and having widespread effects across the eastern Mediterranean region.[13] Volcanic events of this magnitude are known to generate tsunamis and archaeological evidence suggests that such a tsunami may have devastated the Minoan fleet and coastal settlements on Crete.[10][4] Such an event would have been noticed as far as Egypt, as a period of darkness. Egyptians could have told Solon about such an event.[4] Plato did not describe a volcanic eruption, although the events he described as "sunk by an earthquake" or "violent earthquakes, and only a flood (in singular)", could perhaps be interpreted as consistent with such an eruption and the resulting tsunami.[14]

- Ferdinand André Fouqué reported that two golden rings were found under the pumice at Thera. Gold is not found in the area so they must have come by trade.[4]

- Egyptians may have also told Solon of the Sea Peoples' invasion. The event may have been combined, accidentally or intentionally, with the Santorini eruption about 250 years before the invasion.[4]

- Plato described quarries on Atlantis where "one kind of stone was white, another black, and a third red",[15] which are common colors of volcanic rock.

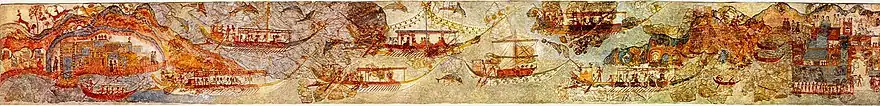

- The center of the metropolis of Atlantis was described as being laid out in circular manner, surrounded by three circular concentric pits of seawater and two earth-rings, each connected to the sea by a deep canal. Docks for a large number of ships, with a causeway, were also mentioned. Scientists reconstructing the shape of the island prior to the eruption have concluded that there was a ring configuration with only one narrow entrance to a larger lagoon with islands inside, much as Plato described.[16] One fresco in the ruins of Akrotiri is believed to be a landscape of the city. It shows a large city in an island in the center of the caldera lagoon.

In mainland Greece

The classicist Robert L. Scranton argued in an article published in Archaeology that Atlantis was the "Copaic drainage complex and its civilization" in Lake Copais, Boeotia.[17] Modern archaeological discoveries have revealed a Mycenaean-era drainage complex and subterranean channels in the lake.

Near Cyprus

It has been argued by Robert Sarmast, an American architect, that the lost city of Atlantis lies at the bottom of the eastern Mediterranean within the Cyprus Basin.[18] In his book and on his web site, he argues that images prepared from sonar data of the sea bottom of the Cyprus Basin southeast of Cyprus show features resembling man-made structures on it at depths of 1,500 meters. He interprets these features as being artificial structures that are part of the lost city of Atlantis as described by Plato. According to his ideas, several characteristics of Cyprus, including the presence of copper and extinct Cyprus dwarf elephants and local place names and festivals (Kataklysmos), support his identification of Cyprus as once being part of Atlantis. As with many other theories concerning the location of Atlantis, Sarmast speculates that its destruction by catastrophic flooding is reflected in the story of Noah's Flood in Genesis.

In part, Sarmast[18] bases his theory that Atlantis can be found offshore of Cyprus beneath 0.9 mile (1.5 km) of water on an abundance of evidence that the Mediterranean Sea dried up during the Messinian Salinity Crisis when its level dropped by 2 to 3 miles (3.2 to 4.9 km) below the level of the Atlantic Ocean as the result of tectonic uplift blocking the inflow of water through Strait of Gibraltar.[19] Separated from the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea either partly or completely dried up as the result of evaporation. As a result, its formerly submerged bottom turned into a desert with large saline and brackish lakes. This whole area was flooded when a ridge collapsed allowing the catastrophic flooding through the Straits of Gibraltar. However, Sarmast disagrees with mainstream geologists, oceanographers, and paleontologists[20][21] in arguing that the closing of the Straits of Gibraltar; the desiccation and subaerial exposure of the floor of the Mediterranean Sea; and its catastrophic flooding has occurred "forty times or more times in its long and turbulent existence" and that "the age of each of these events is unknown."[22] In the same interview, he also contradicts what mainstream geologists, oceanographers, and paleontologists argue[20][21] in claiming that "Scientists know that roughly 18,000 years ago, there was not just one Mediterranean Sea, but three." However, he does not specify who these scientists are; nor does he cite peer-reviewed scientific literature that supports this claim.

Marine and other geologists,[19][23] who have also studied the bottom of the Cyprus basin, and professional archaeologists completely disagree with his interpretations.[24] Investigations by Dr. C. Hübscher of the Institut für Geophysik, Universität Hamburg, Germany, and others of the salt tectonics and mud volcanism within the Cyprus Basin, eastern Mediterranean Sea, demonstrated that the features which Sarmast interprets to be Atlantis consist only of a natural compressional fold caused by local salt tectonics and a slide scar with surficial compressional folds at the downslope end and sides of the slide.[23] This research collaborates seismic data shown and discussed in the Atlantis: New Revelations 2-hour Special episode of Digging for the Truth, a History Channel documentary television series. Using reflection seismology, this documentary demonstrated techniques that what Sarmast interpreted to be artificial walls are natural tectonic landforms.

Furthermore, the interpretation of the age and stratigraphy of sediments blanketing the bottom of the Cyprus Basin from sea bottom cores containing Pleistocene and older marine sediments and thousands of kilometers of seismic lines from the Cyprus and adjacent basins clearly demonstrates that the Mediterranean Sea last dried up during the Messinian Salinity Crisis between 5.59 and 5.33 million years ago.[19][23][25][26][27] For example, research conducted south of Cyprus as part of Leg 160 of the Ocean Drilling Project recovered from Sites 963, 965, and 966 cores of sediments underlying the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea at depths as shallow as 470, 1506, and 1044 meters (1540, 4940, and 3420 ft) below sea level. Thus, these cores came from parts of sea bottom of the eastern Mediterranean Sea that either lie above or at the depth of Sarmast's Atlantis, which lies at depths between 1470 and 1510 meters (4820 and 4950 ft) below mean sea level.[23] These cores provide a detailed and continuous record of sea level that demonstrates that for millions of years at least during the entire Pliocene, Pleistocene, and Holocene epochs that the feature that Sarmast interprets to be Atlantis and its adjacent sea bottom were always submerged below sea level.[25] Therefore, the entire Cyprus Basin, including the ridge where Sarmast claims that Atlantis is located, has been submerged beneath the Mediterranean Sea for millions of years.[21] Since its formation, the sea bottom feature identified by Sarmast as "Atlantis" has always been submerged beneath over a kilometer of water.[23]

Helike

A. Giovannini has argued that the submergence of the Greek city of Helike in 373 BC, i.e. while Plato was alive, may have been the inspiration for a fictional story about Atlantis.[28] The claim that Helike is the inspiration for Plato's Atlantis is also supported by Dora Katsonopoulou and Steven Soter.[29]

Sardinia

The concept of the identification of Atlantis with the island of Sardinia is the idea that the Italians were involved in the Sea Peoples movement (a similar story to Plato's account), that the name "Atlas" may have been derived from "Italos" via the Middle Egyptian language, and Plato's descriptions of the island and the city of Atlantis share several traits with Sardinia and its Bronze Age culture.[30][31]

Malta

Malta, being situated in the dividing line between the western and eastern Mediterranean Sea, and being home to some of the oldest man-made structures in the world, is considered a possible location of Atlantis both by some current researchers[32] and by Maltese amateur enthusiasts.[33]

In the 19th century, the antiquarian Giorgio Grognet de Vassé published a short compendium detailing the theory that Malta was the location of Atlantis. His theory was inspired by the discovery of the megalithic temples of Ġgantija and Ħaġar Qim during his lifetime.[34]

In Malta fdal Atlantis (Maltese remains of Atlantis) (2002), Francis Galea writes about several older studies and hypotheses, particularly that of Maltese architect Giorgio Grongnet, who in 1854 thought that the Maltese Islands are the remnants of Atlantis.[35] However, in 1828, the same Giorgo Grongnet was involved in a scandal concerning forged findings which were intended to provide a "proof" for the claim that Malta was Atlantis.[36]

North-East of Egypt: From Middle East to the Black Sea

Turkey

Peter James, in his book The Sunken Kingdom, identifies Atlantis with the kingdom of Zippasla. He argues that Solon did indeed gather the story on his travels, but in Lydia, not Egypt as Plato states; that Atlantis is identical with Tantalis, the city of Tantalus in Asia Minor, which was (in a similar tradition known to the Greeks) said to have been destroyed by an earthquake; that the legend of Atlantis' conquests in the Mediterranean is based on the revolution by King Madduwattas of Zippasla against Hittite rule; that Zippasla is identical with Sipylus, where Greek tradition placed Tantalis; and that the now vanished lake to the north of Mount Sipylus was the site of the city.[37]

Troy

The geoarchaeologist Eberhard Zangger has proposed the hypothesis that Atlantis was in fact the city state of Troy.[38] He both agrees and disagrees with Rainer W. Kühne: He too believes that the Trojans-Atlanteans were the sea peoples, but only a minor part of them. He proposes that all Greek speaking city states of the Aegean civilization or Mycenae constituted the sea peoples and that they destroyed each other's economies in a series of semi-fratricidal wars lasting several decades.[39]

Black Sea

.png.webp)

German researchers Siegfried and Christian Schoppe locate Atlantis in the Black Sea. Before 5500 BC, a great plain lay in the northwest at a former freshwater-lake. In 5510 BC, rising sea level topped the barrier at today's Bosporus. They identify the Pillars of Hercules with the Strait of Bosporus.[41] They gave no explanation how the ships of the merchants coming from all over the world had arrived at the harbour of Atlantis when it was 350 feet below global sea-level.

They claim Oreichalcos means the obsidian stone that used to be a cash-equivalent at that time and was replaced by the spondylus shell around 5500 BC, which would suit the red, white, black motif. The geocatastrophic event led to the neolithic diaspora in Europe, also beginning 5500 BC.

In 2000, the Guardian reported that Robert Ballard, in a small submarine, found remains of human habitation around 300 feet underwater in the Black Sea off the north coast of Turkey. The area flooded around 5000 BC. This flood is also thought to have inspired the Biblical story of Noah's Ark known as the Black Sea deluge theory.

The Great Atlantis Flood, by Flying Eagle & Whispering Wind, locates Atlantis in the Sea of Azov. The theory proposes that the Dialogues of Plato present an accurate account of geological events, which occurred in 9,600 BC, in the Black Sea-Mediterranean Corridor. Glacial melt-waters, at the end of the Younger Dryas Ice Age caused a dramatic rise in the sea level of the Caspian Sea. An earthquake caused a fracture, which allowed the Caspian Sea to flood across the fertile plains of Atlantis. Simultaneously the earthquake caused the vast farmlands of Atlantis to sink, forming the present day Sea of Azov, the shallowest sea in the world.[42]

Around Gibraltar: Near the Pillars of Hercules

Andalusia

Andalusia is a region in modern-day southern Spain which once included the "lost" city of Tartessos, which disappeared in the 6th century BC. The Tartessians were traders known to the Ancient Greeks who knew of their legendary king Arganthonios. The Andalusian hypothesis was originally developed by the Spanish author Juan de Mariana and the Dutch author Johannes van Gorp (Johannes Goropius Becanus), both of the 16th century, later by José Pellicer de Ossau Salas y Tovar in 1673, who suggested that the metropolis of Atlantis was between the islands Mayor and Menor, located almost in the center of the Doñana Marshes,[43] and expanded upon by Juan Fernández Amador y de los Ríos in 1919, who suggested that the metropolis of Atlantis was located precisely where today are the 'Marismas de Hinojo'.[44] These claims were made again in 1922 by the German author Adolf Schulten, and further propagated by Otto Jessen, Richard Hennig, Victor Berard, and Elena Wishaw in the 1920s. The suggested locations in Andalusia lie outside the Pillars of Hercules, and therefore beyond but close to the Mediterranean itself.

In 2005, based upon the work of Adolf Schulten, the German teacher Werner Wickboldt also claimed this to be the location of Atlantis.[45] Wickboldt suggested that the war of the Atlanteans refers to the war of the Sea Peoples who attacked the Eastern Mediterranean countries around 1200 BC and that the Iron Age city of Tartessos may have been built at the site of the ruined Atlantis. In 2000, Georgeos Diaz-Montexano published an article explaining his theory that Atlantis was located somewhere between Andalusia and Morocco.[46]

An Andalusian location was also supported by Rainer Walter Kühne in his article that appeared in the journal Antiquity.[47][48] Kühne's theory says: "Good fiction imitates facts. Plato declared that his Atlantis tale is philosophical fiction invented to describe his fictitious ideal state in the case of war. Kühne suggests that Plato has used three different historical elements for this tale. (i) Greek tradition on Mycenaean Athens for the description of ancient Athens, (ii) Egyptian records on the wars of the Sea Peoples for the description of the war of the Atlanteans, and (iii) oral tradition from Syracuse about Tartessos for the description of the city and geography of Atlantis." According to Wickboldt, Satellite images show two rectangular shapes on the tops of two small elevations inside the marsh of Doñana which he hypothesizes are the "temple of Poseidon" and "the temple of Cleito and Poseidon".[49] On satellite images parts of several "rings" are recognizable, similar in their proportion with the ring system by Plato.[45] It is not known if any of these shapes are natural or manmade and archaeological excavations are planned.[50] Geologists have shown that the Doñana National Park experienced intense erosion from 4000 BC until the 9th century AD, where it became a marine environment. For thousands of years until the Medieval Age, all that occupied the area of the modern Marshes Doñana was a gulf or inland sea-arm, but there was not even a small island with sufficient space to house a small village.[51][52]

Spartel Bank

Two hypotheses have put Spartel Bank, a submerged former island in the Strait of Gibraltar, as the location of Atlantis. The more well-known hypothesis was proposed in a September 2001 issue of Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences by French geologist Jacques Collina-Girard.[53] The lesser-known hypothesis was first published by Spanish-Cuban investigator Georgeos Díaz-Montexano in an April 2000 issue of Spanish magazine Más Allá de la Ciencia (Beyond Science), and later in August 2001 issues of Spanish magazines El Museo (The Museum) and Año Cero (Year Zero).[54] The origin of Collina-Girard's hypothesis is disputed, with Díaz-Montexano claiming it as plagiarism of his own earlier hypothesis, and Collina-Girard denying any plagiarism. Both individuals claim the other's hypothesis is pseudoscience.[54][55]

Collina-Girard's hypothesis states that during the most recent Glacial Maximum of the Ice Age sea level was 135 m below its current level, narrowing the Gibraltar Strait and creating a small half-enclosed sea measuring 70 km by 20 km between the Mediterranean and Atlantic Ocean. The Spartel Bank formed an archipelago in this small sea with the largest island measuring about 10 to 12 kilometers across. With rising ocean levels the island began to slowly shrink, but then at around 9400 BC (11,400 years ago) there was an accelerated sea level rise of 4 meters per century known as Meltwater pulse 1A, which drowned the top of the main island. The occurrence of a great earthquake and tsunami in this region, similar to the 1755 Lisbon earthquake (magnitude 8.5-9) was proposed by marine geophysicist Marc-Andrè Gutscher as offering a possible explanation for the described catastrophic destruction (reference — Gutscher, M.-A., 2005. Destruction of Atlantis by a great earthquake and tsunami? A geological analysis of the Spartel Bank hypothesis. Geology, v. 33, p. 685-688.) .[56] Collina-Girard proposes that the disappearance of this island was recorded in prehistoric Egyptian tradition for 5,000 years until it was written down by the first Egyptian scribes around 4000-3000 BC, and the story then subsequently inspired Plato to write a fictionalized version interpreted to illustrate his own principles.

A detailed review in the Bryn Mawr Classical Review comments on the discrepancies in Collina-Girard's dates and use of coincidences, concluding that he "has certainly succeeded in throwing some light upon some momentous developments in human prehistory in the area west of Gibraltar. Just as certainly, however, he has not found Plato's Atlantis."[57]

Northwest Africa

Morocco

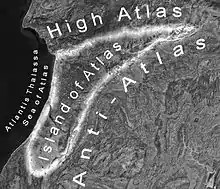

According to Michael Hübner, Atlantis core region was located in South-West Morocco at the Atlantic Ocean. In his papers[58][59][60] an approach to the analysis of Plato's dialogues Timaeus and Critias is described. By means of a hierarchical constraint satisfaction procedure, a variety of geographically relevant indications from Plato's accounts are used to infer the most probable location of Plato's Atlantis Nesos. The outcome of this is the Souss-Massa plain in today's South-West Morocco. This plain is surrounded by the High Atlas, the Anti-Atlas, the Sea of Atlas (Atlantis Thalassa, today's Atlantic Ocean). Because of this isolated position, Hübner argued, this plain was called Atlantis Nesos, the Island of Atlas by ancient Greeks before the Greek Dark Ages. The Amazigh (Berber) People actually call the Souss-Massa plain island. Of major archaeological interest is the fact that in the North-West of the Souss-Massa plain a large annular caldera-like geomorphologic structure was discovered. This structure has almost the dimensions of Plato's capital of Atlantis and is covered with hundreds of large and small prehistoric ruins of different types.[61] These ruins were made out of rocks coloured red, white and black. Hübner also shows possible harbour remains, an unusually geomorphological structure, which applies to Plato's description of roofed over docks, which were cut into red, white and black bedrock. These 'docks' are located close to the annular geomorphological structure and close to Cape Ghir, which was named Cape Heracles in antiquity. Hübner also argued, that Agadir is etymologically related to the semitic g-d-r and probably to Plato's Gadir. The semitic g-d-r means enclosure, fortification and sheep fold.[62] The meaning of enclosure, sheep fold corresponds to the Greek translation of the name Gadeiros (Crit. 114b) which is Eumelos = Rich in Sheep.[63]

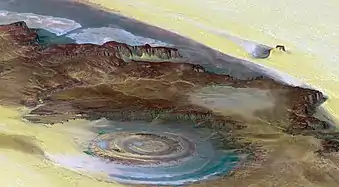

Richat Structure, Mauritania

The Richat Structure in Mauritania has also been proposed as the site of Atlantis.[64][65] This structure is generally considered to be a deeply eroded domal structure that overlies a still-buried alkaline igneous intrusion.[66] From 1974 onward,[67] prehistoric artifacts of the area were mapped, finding an absence of prehistoric artifacts or Paleolithic or Neolithic stone tools from the structure's innermost depressions. Neither recognizable midden deposits nor manmade structures were found nor reported in the area, thus concluding that the area was used only for short-term hunting and stone tool manufacturing during prehistoric times.[68][69]

In September 2018 the YouTube channel Bright Insight claimed that the Richat Structure's features match Solon's description of Atlantis;[70][71][72] with over 3.8 million views and the story covered in Germany's Der Spiegel,[70] Vietnam's Tien Phong,[71] Business Insider Australia,[73] and the main UK tabloids. Bright Insight claimed that matching features included 5 concentric circles, the diameter (127 stadia or 23.5 km), a waterway outlet to the south, salty groundwater everywhere except below the centerpoint, and mountains with waterfalls sheltering the city on the north. The present location, elevated and away from any body of water was explained by the lakes and rivers once present across the Sahara, and by a gradual rise of the land of about 2.5 cm per year.[72]

Atlantic Ocean: West

It has been thought that when Plato wrote of the Sea of Atlantis, he may have been speaking of the area now called the Atlantic Ocean. The ocean's name, derived from Greek mythology, means the "Sea of Atlas". Plato remarked that, in describing the origins of Atlantis, this area was allotted to Poseidon. In Ancient Greek times the terms "Ocean" and "Atlas" both referred to the 'Giant Water' which surrounded the main landmass known at that time by the Greeks, which could be described as Eurafrasia (although this whole supercontinent was far from completely known to the Ancient Greeks), and thus this water mass was considered to be the 'end of the (known) world', for the same reason the name "Atlas" was given to the mountains near the Ocean, the Atlas Mountains, as they also denoted the 'end of the (known) world'.

Azores Islands

One of the suggested places for Atlantis is around the Azores Islands, a group of islands belonging to Portugal located about 900 miles (1500 km) west of the Portuguese coast. Some people believe the islands could be the mountain tops of Atlantis. Ignatius L. Donnelly, an American congressman, was perhaps the first one to talk about this possible location in his book Atlantis: The Antediluvian World.[74] Ignatius L. Donnelly also makes a connection to the mythical Aztlán.

Charles Schuchert, in a paper called "Atlantis and the Permanency of the North Atlantic Ocean Bottom" (1917), discussed a lecture by Pierre-Marie Termier in which Termier suggested "that the entire region north of the Azores and perhaps the very region of the Azores, of which they may be only the visible ruins, was very recently submerged", reporting evidence that an area of 40,000 sq. mi and possibly as large as 200,000 sq. mi. had sunk 10,000 feet below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean. Schuchert's conclusion was: "(1) that the Azores are volcanic islands and are not the remnants of a more or less large continental mass, for they are not composed of rocks seen on the continents; (2) that the tachylytes dredged up from the Atlantic to the north of the Azores were in all probability formed where they are now, at the bottom of the ocean; and (3) that there are no known geologic data that prove or even help to prove the existence of Plato's Atlantis in historic times."[75]

The Azores are steep-sided volcanic seamounts that drop rapidly 1000 meters (about 3300 feet) to a plateau.[76] Cores taken from the plateau and other evidence shows that this area has been an undersea plateau for millions of years.[77][78] Ancient indicators, i.e. relict beaches, marine deposits, and wave cut-terraces, of Pleistocene shorelines and sea level show that the Azores Islands have not subsided to any significant degree. Instead, they demonstrate that some of these islands have actually risen during the Late and Middle Pleistocene. This is evidenced by relict, Pleistocene wave-cut platforms and beach sediments that now lie well above current sea level. For example, they have been found on Flores Island at elevations of 15-20, 35-45, ~100, and ~250 meters above current sea level.[79]

Three tectonic plates intersect among the Azores, the so-called Azores Triple Junction.[80]

Canary Islands, Madeira and Cape Verde

The Canary Islands have been identified as remnants of Atlantis by numerous authors. For example, in 1803, Bory de Saint-Vincent in his Essai sur les îles fortunées et l'antique Atlantide proposed that the Canary Islands, along with the Madeira, and Azores, are what remained after Atlantis broke up. Many later authors, i.e. Lewis Spence in his The Problem of Atlantis, also identified the Canary Islands as part of Atlantis left over from when it sank.

Detailed geomorphic and geologic studies of the Canary Islands clearly demonstrate that over the last 4 million years, they have been steadily uplifted, without any significant periods of subsidence, by geologic processes such as erosional unloading, gravitational unloading, lithospheric flexure induced by adjacent islands, and volcanic underplating.[81] For example, Pliocene pillow lavas, which solidified underwater and now exposed on the northeast flanks of Gran Canaria, have been uplifted between 46 and 143 meters above sea level.[81] Also, marine deposits associated with lavas dated as being 4.1 and 9.3 million years old in Gran Canaria, ca. 4.8 million years old in Fuerteventura, and ca. 9.8 million years old in Lanzarote demonstrate that the Canary Islands have for millions of years undergone long term uplift without any significant, much less catastrophic, subsidence.[82][83] A series of raised, Pleistocene marine terraces, which become progressively older with increasing elevation, on Fuerteventura indicate that it has risen in elevation at about 1.7 cm per thousand years for the past one million years. The elevation of the marine terrace for the highstand of sea level for the last interglacial period shows that this island has experienced neither subsidence nor significant uplift for the past 125,000 years.[84] Within the Cape Verde Islands, the detailed mapping and dating of 16 Pleistocene marine terraces and Pliocene marine conglomerate found that they have been uplifted throughout most of the Pleistocene and remained relatively stable without any significant subsidence since the last interglacial period.[85] Finally, detailed studies of the sedimentary deposits surrounding the Canary Islands have demonstrated, except for a narrow rim around each island exposed during glacial lowstands of sea level, a complete lack of any evidence for the ocean floor surrounding the Canary Islands having ever been above water.[86][87]

Northern Spain

According to Jorge Maria Ribero-Meneses,[88] Atlantis was in northern Spain. He specifically argues that Atlantis is the underwater plateau, known internationally as "Le Danois Bank" and locally as "The Cachucho". It is located about 25 kilometers from the continental shelf and about 60 km off the coast of Asturias, and Lastres between Ribadesella. Its top is now 425 meters below the sea. It is 50 kilometers from east to west and 18 km from north to south. Ribero-Meneses hypothesized that is part of the continental margin that broke off at least 12000 years ago as the result of tectonic processes that occurred at the end of the last ice age. He argues that they created a tsunami with waves with heights of hundreds of meters and that the few survivors had to start virtually from scratch.[89]

Detailed studies[90] of the geology of the Le Danois Bank region have refuted the hypothesis proposed by Jorge Maria Ribero-Meneses that the Le Danois Bank was created by the collapse of the northern Cantabrian continental margin about 12,000 years ago. The Le Danois Bank represents part of the continental margin that have been uplifted by thrust faulting when the continental margin overrode oceanic crust during the Paleogene and Neogene periods. Along the northern edge of the Le Danois Bank, Precambrian granulite and Mesozoic sedimentary rocks have been thrust northward over Miocene and Oligocene marine sediments. The basin separating the Le Danois Bank from the Cantabrian continental margin to the south is a graben that simultaneously formed as a result of normal faulting associated with the thrust faulting.[90][91] In addition, marine sediments that range in age from lower Pliocene to Pleistocene, cover large parts of Le Danois Bank, and fill the basin separating it from the Cantabrian continental margin demonstrate that this bank has been submerged beneath the Bay of Biscay for millions of years.[92][93]

Atlantic Ocean: North

Irish Sea

In his book Atlantis of the West: The Case For Britain's Drowned Megalithic Civilization (2003), Paul Dunbavin argues that a large island once existed in the Irish Sea and that this island was Atlantis. He argues that this Neolithic civilization in Europe was partially drowned by rising sea levels caused by a comet impact that caused a pole shift and changed the earth's axis around 3100 BC.[94] Such changes would be readily detectable to modern science, however, and Dunbavin's claims are considered pseudo-scientific at best within the scientific community.

Great Britain

William Comyns Beaumont believed that Great Britain was the location of Atlantis[95] and the Scottish journalist Lewis Spence claimed that the ancient traditions of Britain and Ireland contain memories of Atlantis.

On December 29, 1997, the BBC reported that a team of Russian scientists believed they found Atlantis in the ocean 100 miles off of Land's End, Cornwall, Britain. The BBC stated that Little Sole Bank, a relatively shallow area, was believed by the team to be the capital of Atlantis. This may have been based on the myth of Lyonesse.[96]

Ireland

The idea of Atlantis being located in Ireland was presented in the book Atlantis from a Geographer's Perspective: Mapping the Fairy Land (2004) by Swedish geographer Dr. Ulf Erlingsson from Uppsala University. It hypothesized that the empire of Atlantis refers to the Neolithic Megalithic tomb culture, based on their similar geographic extent, and deduced that the island of Atlantis then must correspond to Ireland. Erlingsson found the similarities of size and landscape to be statistically significant, while he rejected his null hypothesis that Plato invented Atlantis as fiction.[97]

North Sea

The North Sea is known to contain lands that were once above water; the medieval town of Dunwich in East Anglia, for example, crumbled into the sea. The land area known as "Doggerland", between England and Denmark, was inundated by a tsunami around 8200BP (6200BC), caused by a submarine landslide off the coast of Norway known as the Storegga Slide,[98] and prehistoric human remains have been dredged up from the Dogger Bank.[99] Atlantis itself has been identified besides Heligoland off the north-west German coast by the author Jürgen Spanuth,[100] who postulates that it was destroyed during the Bronze Age around 1200 BC, only to partially re-emerge during the Iron Age. Ulf Erlingsson hypothesized that the island that sank referred to Dogger Bank, and the city itself referred to the Silverpit crater at the base of Dogger Bank. A book allegedly by Oera Linda claims that a land called Atland once existed in the North Sea, but was destroyed in 2194 BC.

Denmark

In his book The Celts: The People Who Came Out of the Darkness (1975), author Gerhard Herm links the origins of the Atlanteans to the end of the ice age and the flooding of eastern coastal Denmark.[101]

Finland

Finnish eccentric Ior Bock located Atlantis in the Baltic sea, at southern part of Finland where he claimed a small community of people lived during the Ice Age. According to Bock, this was possible due to Gulf Stream which brought warm water to the Finnish coast. This is a small part of a large "saga" that he claimed had been told in his family through the ages, dating back to the development of language itself. The family saga tells the name Atlantis comes from Swedish words allt-land-is ("all-land-ice") and refers to the last Ice-Age. Thus in the Bock family saga it's more a time period than an exact geographical place. According to this the Atlantis disappeared in 8016 BC when the Ice-Age ended in Finland and the ice melted away.[102]

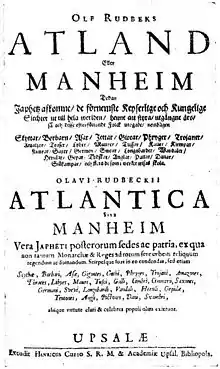

Sweden

In 1679 Olaus Rudbeck wrote Atlantis (Atlantica), where he argues that Scandinavia, specifically Sweden, is identical with Atlantis.[103][104] According to Rudbeck the capital city of Atlantis was identical to the ancient burial site of Swedish kings Gamla Uppsala.

Americas

Until the discovery of the New World many scholars believed that Atlantis was either a metaphor for teaching philosophy, or just attributed the story to Plato without connecting the island with a real location. When Columbus returned from his voyage to the west historians began identifying the Americas with Atlantis. The first was Francisco López de Gómara,[4][105] who in 1552 thought that what Columbus had discovered was the Atlantic Island of Plato.

In 1556 Agustín de Zárate stated that the Americas was Atlantis which at one time began from the straits of Gibraltar and extended westwards to include North and South America and that it was as a result of Plato that the new continent was discovered. He also said it had all the attributes of the continent described by Plato yet at the same time mentioned that the ancient peoples crossed over by a route from the island of Atlantis. Zarate also mentions that the 9,000 "years" of Plato were 9,000 "months" (750 years).[106]

This was also repeated and clarified by historian Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa in 1572 in his "History of the Incas",[107] who by calculation of longitude stated that Atlantis must have stretched from within two leagues of the strait of Gibraltar westwards to include "all the rest of the land from the mouth of the Marañon (Amazon River) and Brazil to the South Sea, which is what they now call America." He thought the sunken part to be now in the Atlantic Ocean but that it was from this sunken part that the original Indians had come to populate Peru via one continuous land mass. He says that South America was also known by the name of the Isla Atlanticus.

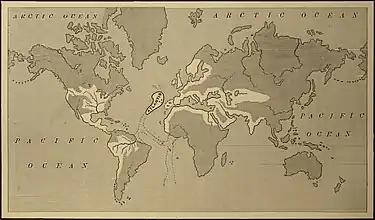

It first appeared as the Atlantic Island (Insula Atlantica) on a map of the New World by cartographer Sebastian Münster in 1540[108] and again on the map titled Atlantis Insula by Nicolas Sanson and son (1669) which identified both North and South America as "Atlantis Insula", the eastern part of the Atlantic Ocean as "Oceanus Atlanticus" and the western part of the Atlantic Ocean plus the Pacific Ocean as "Atlanticum Pelagus". This edition was further embellished with features from the Atlantis legend by his son Guillaume Sanson including the names of the ten kings of Atlantis with Atlas' portion being in Mexico. Sanson's map supposedly showed what the earth looked like 200,000 years before there were any humans on it.[109]

Francis Bacon and Alexander von Humboldt also identified America with Atlantis; Janus Joannes Bircherod said in 1663 orbe novo non novo ("the New World is not new").[4]

Antarctica

The theory that Antarctica was Atlantis was particularly fashionable during the 1960s and 1970s, spurred on partly both by the isolation of the continent, and also the Piri Reis map, which purportedly shows Antarctica as it would be ice free, suggesting human knowledge of that period. Flavio Barbiero, Charles Berlitz, Erich Von Däniken and Peter Kolosimo are some of the popular authors who made this proposal.

More recently Rose and Rand Flem-Ath have proposed this in their book, When the Sky Fell; the theory was revised and made more specific in Rand's work with author Colin Wilson, in The Atlantis Blueprint (published in 2002). The second work theorized that Atlantis was to be found in Lesser Antarctica, near the coast of the Ross Ice Shelf. A geological theory known as "Earth Crust Displacement" forms the basis of their work. The Atlantis Blueprint uses both scientific and pseudoscientific (such as mere speculation and assumptions) means to back up the theory.[110]

Charles Hapgood came up with the "Earth Crustal Displacement theory". Hapgood's theory suggests that Earth's outer crust is able to move upon the upper mantle layer rapidly up to a distance of 2,000 miles, placing Atlantis in Antarctica, when considering the movements of the crust in the past. Albert Einstein was one of the few voices to answer Hapgood's theory. Einstein wrote a preface for Hapgood's book Earth's shifting crust, published in 1958. This theory is particularly popular with Hollow Earthers, and can be seen as a mirror of the Hyperborean identification.[111] In his book "Fingerprints of the Gods", author Graham Hancock argues for the Earth Crustal Displacement theory in general, and the Atlantis/Antarctica connection specifically, then goes on to propose archaeological exploration of Antarctica in search of Atlantis.

North Pole

The professor of systematic theology at Boston University William Fairfield Warren (1833–1929) wrote a book promoting his theory that the original centre of mankind once sat at the North Pole entitled Paradise Found: The Cradle of the Human Race at the North Pole (1885). In this work Warren placed Atlantis at the North Pole, as well as the Garden of Eden, Mount Meru, Avalon and Hyperborea.[112] Warren believed all these mythical lands were folk memories of a former inhabited far northern seat where man was originally created.[113]

See also

References and notes

- Ignatius L. Donnelly (1882). Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. Harper. p. 295. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- Babiniotis, Lexicon of the Greek Language. Pelagos = Small Open sea

- "The Egyptian legend of Atlantis—also current in folk-tale along the Atlantic seaboard from Gibraltar to the Hebrides, and among the Yorub in West Africa—is not to be dismissed as pure fancy, and seems to date from the third millennium BC. But Plato's version, which he claims that Solon learned from his friends the Libyan priests of Sais in the Delta, he apparently been grafted on a later tradition: how the Minoan Cretans who had extended their influence to Egypt and Italy, were defeated a Hellenic confederacy with Athens at its head; and whom, perhaps as the result of a submarine earthquake, the enormous harbour works built by the Keftiu ('sea-people', meaning the Cretans and their allies) on the island of Pharos and, subsided under seven fathoms of water—where they have lately been rediscovered by dive: These works consisted of an outer and an inner basin, together covering some two hundred and. fifty acres (Gaston Jondet: Les Ports submerges l'ancienne île de Pharos). Such an identification of Atlantis with Pharos would account for Atlas’s being sometimes described as a son of Iapetus—the Japhet of Genesis, whom the Hebrews called Noah’s son and made the ancestor of the Sea-people’s confederacy—and sometimes as a son of Poseidon and, though in Greek myth Iapetus appears as Deucalion’s grandfather, this need mean no more than that he was the eponymous ancestor of the Canaanite tribe which brought the Mesopotamian Flood legend rather than the Atlantian, to Greece. Several details in Plato’s account such as the pillar sacrifice of bulls and the hot-and-cold water systems in Atlas’s palace, make it certain that the Cretans are being described, and no other nation." (Graves, 1955)

- Ley, Willy (June 1967). "Another Look at Atlantis". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 74–84.

- Galanopoulos, Angelos G. (1960): On the Location and Size of Atlantis, in: Praktika Akademia Athenai 35 (1960) 401-418.

- Frost, K. T. (1913): "The Critias and Minoan Crete", in: Journal of Hellenic Studies 33 (1913) 189-206. Balch, E. S. (1917): "Atlantis or Minoan Crete", in: The Geographical Review 3 (1917) 388-392. Marinatos, Spyridon (1950): "Peri ton Thrulon tes Atlantidos", in: Kretica Chronica 4 (1950) 195-213. Andrews, P. B. S. (1967): "Larger than Africa and Asia?", in: Greece and Rome 14 (1967) 76-79, Charles Pellegrino (1991): Unearthing Atlantis: An Archaeological Odyssey.

- Galanopoulos, Angelos Geōrgiou, and Edward Bacon, Atlantis: The Truth Behind the Legend, Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1969

- "Santorini Eruption (~1630 BC) and the legend of Atlantis". Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Vergano, Dan (2006-08-27). "Ye gods! Ancient volcano could have blasted Atlantis myth". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Lilley, Harvey (20 April 2007). "The wave that destroyed Atlantis". BBC Timewatch. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- "Lost Worlds: CGI: Atlantis". History.com. Archived from the original on March 19, 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- "Lost Worlds: Atlantis". History Channel UK. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- "Santorini eruption much larger than originally believed". August 23, 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- "Santorini and the legend of Atlantis: The Minoan eruption on Santorini as possible origin?". Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- Arundell (1885). The Secret of Plato's Atlantis. Burns and Oates. p. 92. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- "Models of the Pre-Minoan Island (prior to ca. 1645 BC)". Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- Scranton, R. L. (1949). "Lost Atlantis found again?". Archaeology. 2 (3): 159–162. JSTOR 41662314.

- Sarmast, R., 2006, Discovery of Atlantis: The Startling Case for the Island of Cyprus. Origin Press, San Rafael, California. 195 pp. ISBN 1-57983-012-9

- Clauzon, G.; Suc, J.-P.; Gautier, F.; Berger, A.; Loutre, M.-F. (1996). "Alternate interpretation of the Messinian salinity crisis: Controversy resolved?". Geology. 24 (4): 363–366. Bibcode:1996Geo....24..363C. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1996)024<0363:aiotms>2.3.co;2.

- Stanley, D.J., and F.-C. Wezel, 1985, "Geological Evolution of the Mediterranean Basin" Springer-Verlag, New York. 589 p. ISBN 1-897799-66-7

- Hall, J.K., V.A. Krasheninnikov, F. Hirsch, C. Benjamini, and C. Flexer, eds., 2005, "Geological framework of the Levant, Volume II: the Levantine Basin and Israel", 107 MB PDF version, Historical Productions-Hall, Jerusalem, Israel. 826 p. Additional PDF files of a related book and maps can be downloaded from "CYBAES manuscript downloads"

- Hübscher, C.; Tahchi, E.; Klaucke, I.; Maillard, A.; Sahling, H. (2009). "Salt tectonics and mud volcanism in the Latakia and Cyprus Basins, eastern Mediterranean" (PDF). Tectonophysics. 470 (1–2): 173–182. Bibcode:2009Tectp.470..173H. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2008.08.019.

- Britt, R.R., 2004, Claimed Discovery of Atlantis Called 'Completely Bogus, Live Science.

- Emeis, K.-C., A.H.F. Robertson, C. Richter, and others, 1996, ODP Leg 160 (Mediterranean I) Sites 963-973 Proceedings Ocean Drilling Program Initial Reports no. 160. Ocean Drilling Program, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas. ISSN 1096-2158

- Calon, T.J.; Aksu, A.E.; Hall, J. (2005). "The Neogene evolution of the Outer Latakia Basin and its extension into the Eastern Mesaoria Basin (Cyprus), Eastern Mediterranean". Marine Geology. 221 (1–4): 61–94. Bibcode:2005MGeol.221...61C. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2005.03.013.

- Hall, J.; Calon, T.J.; Aksu, A.E.; Meade, S.R. (2005). "Structural evolution of the Latakia Ridge and Cyprus Basin at the front of the Cyprus Arc, Eastern Mediterranean Sea". Marine Geology. 221 (1–4): 261–297. Bibcode:2005MGeol.221..261H. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2005.03.007.

- Giovannini, A. (1985). "Peut-on démythifier l'Atlantide?". Museum Helveticum (in French). 42: 151–156. ISSN 0027-4054.

- Paul Kronfield. "Helike Foundation - Discoveries at Ancient Helike". Helike.org. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- Thorwald C. Franke: King Italos = King Atlas of Atlantis? A contribution to the Sea Peoples, in: Stavros P. Papamarinopoulos (editor), Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on "The Atlantis Hypothesis" (ATLANTIS 2008), 10–11 November 2008 Athens/Greece, Publisher: Heliotopos Conferences / Heliotopos Ltd., Athens 2010; pp. 169-180. Cf. Atlantis-scout.de (in English)

- Thorwald C. Franke: Mit Herodot auf den Spuren von Atlantis, Norderstedt 2006 (German)

- Times of Malta 2006-11-14: Is Malta really part of Atlantis? Retrieved 2011-05-08

- Atlantis in Malta, Maltese website devoted to proving that Malta is Atlantis. Retrieved 2011-05-08

- Schiavone, Michael J. (2009). Dictionary of Maltese Biographies Vol. 2 G–Z. Pietà: Pubblikazzjonijiet Indipendenza. p. 989. ISBN 9789993291329.

- Atlantipedia: The Maltese proponents Retrieved 2011-05-08

- Vgl. T. Franke: The Atlantis-Malta Hoax of Fortia d'Urban and Grognet from 1828 resp. August Boeckh, De Titulis Quibusdam Suppositis, in: The Philological Museum Vol. 2 / 1833; pp. 457-467

- James, Peter (1995). The Sunken Kingdom. The Atlantis Mystery Solved. Jonathan Cape.

- Zangger, Eberhard (1993): "Plato's Atlantis Account – A Distorted Recollection of the Trojan War", in: Oxford Journal of Archaeology 18 (1993) 77-87

- Zangger, Eberhard (1992). The Flood from Heaven: Deciphering the Atlantis Legend. William Morrow & Company. ISBN 0-688-11350-8.

- "Mạng Máy Tính – Phần Mềm – Internet – Wifi – Thủ Thuật". Archived from the original on 2008-07-07. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- Siegfried Schoppe and Christian Schoppe (2004-08-12). "Atlantis in the Black Sea". Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- "Great Atlantis Flood". Atlantis-today.com. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- Joseph Pellicer de Ossau Salas y Tovar (Spaniard). Aparato a la mvonarchia antigua de las Españas en los tres tiempos del mundo, el adelon, el mithico y el historico : primera parte... / por don Ioseph Pellicer de Ossau y Touar... (En Valençia : por Benito Macè..., 1673 (the first extensive study about Atlantis in Iberia, with the hypothesis about Doñana)

- Juan Fernández Amador de los Ríos (Spaniard). Antigüedades ibéricas / por Juan Fernández Amador de los Rios. Pamplona : Nemesio Aramburu, 1911. (first part about the Atlantis in Iberia, with the hypothesis about Doñana, Sea Peoples, etc.)

- Werner Wickboldt: Locating the capital of Atlantis by strict observation of the text by Plato. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on "The Atlantis Hypothesis: Searching for a Lost Land" (Milos island 2005) ISBN 978-960-89882-1-7 pp. 517-524

- Magazine Más Allá de la Ciencia, March–April of the 2000 (nº 134), where was published a report about the Georgeos Díaz-Montexano's theory of Atlantis between Andalusia and Morocco.

- Rainer W. Kühne (June 2004). "A location for "Atlantis"?". Antiquity.ac.uk. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- Rainer W. Kühne: "Did Ulysses Travel to Atlantis?" in: "Science and Technology in Homeric Epics" (ed. S. A. Paipetis), Series: History of Mechanism and Machine Science, Vol. 6, Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-1-4020-8783-7

- Paul Rincon (June 6, 2004). "Satellite images 'show Atlantis". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- "Search for Tartessos-Atlantis in the Donana National Park". Beepworld.de. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- A. Rodriguez-Ramirez et al., Recent coastal evolution of the Doñana National Park (SW Spain), in: Quaternary Science Reviews, Vol. 15 (1996) pp.803 -809

- Paleogeografía de las costas atlánticas de Andalucía durante el Holoceno medio-superior : prehistoria reciente, protohistoria y fases históricas / Francisco Borja Barrera En: Tartessos : 25 años después, 1968–1993 : Jerez de la Frontera, 1995, ISBN 84-87194-64-8, pags. 73-97

- Collina-Girard, Jacques (2001): "L'Atlantide devant le détroit de Gibraltar? Mythe et géologie", in: Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences (2a) 333 (2001) 233-240.

- María Fdez-Valmayor (Secretary and sentimental partner of Diaz-Montexano in those time). "Atlantis in Gibraltar, between Iberia and Africa". Archived from the original on April 5, 2004.

- Little, Greg (September 2004). "Atlantis Insider: Brief Reviews of the Latest in the Search for Atlantis". Archived from the original on 2004-09-04.

- Ornekas, Genevra (2005). "Atlantis Rises Again". Science. 722 (1). Archived from the original on 2008-06-21.

- Nesselrath, Heinz-Guenther (2009-09-23). "Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2009.09.64". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- Michael Hübner. "Circumstantial evidence for Plato's Island Atlantis in the Souss-Massa plain in today's South-Morocco".

- Michael Hübner; Sebastian Hübner. "Evidence for a Large Prehistoric Settlement in a Caldera-Like Geomorphologic Structure in Southwest Morocco".

- Proceedings of the International Conference on "The Atlantis Hypothesis: Searching for a Lost Land". Stavros P. Papamarinopoulos, Athens.

- Michael Hübner; Sebastian Hübner. "Large prehistoric settlement in Southwest Morocco discovered". IC-Nachrichten 91 Institutum Canarium.

- Vycichl, W. (July 1952). "Punischer Spracheinfluss im Berberischen" [Punic language influence in the Berber language]. Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 11 (3): 198–204. doi:10.1086/371088. JSTOR 542638. S2CID 162367447.

- Perseus Digital Library (2008). "Eumēlus".

- Mark Adams (26 April 2016). Meet Me in Atlantis: Across Three Continents in Search of the Legendary Sunken City. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-101-98393-5.

Rob Shelsky (23 February 2016). Invader Moon. Simon and Schuster. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-61868-666-4. - Tapon, Francis (30 July 2018). "Going Into The Eye Of The Sahara - The Richat Structure". Forbes. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- Matton, Guillaume; Jébrak, Michel (September 2014). "The "eye of Africa" (Richat dome, Mauritania): An isolated Cretaceous alkaline–hydrothermal complex". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 97: 109–124. Bibcode:2014JAfES..97..109M. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2014.04.006.

- Monod, T (1975). "Trois gisements à galets aménagés dans l'Adrar mauritanien (Sahara occidental)". Provence Historique. 99: 87–97.

- Sao, O.; Giresse, P.; de Lumley, H.; Faure, O.; Perrenoud, C.; Saos, T.; Rachid, M.O.; Touré, O.C. (2008). "Les environnements sédimentaires des gisements pré-acheuléens et acheuléens des wadis Akerdil et Bamouéré (Guelb er-Richât, Adrar, Mauritanie), une première approche". L'Anthropologie. 112 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.anthro.2008.01.001.

- Giresse, P.; Sao, O.; de Lumley, H. (2012). "Étude paléoenvironnementale des sédiments quaternaires du Guelb er Richât (Adrar de Mauritanie) en regard des sites voisins ou associés du Paléolithique inférieur. Discussion et perspectives". L'Anthropologie. 116 (1): 12–38. doi:10.1016/j.anthro.2011.12.001.

- "Satellitenbild der Woche: Das Auge der Sahara ("Satellite photo of the week: The Eye of the Sahara")". Der Spiegel (in German). 31 December 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- "Kỳ lạ 'con mắt thần linh' giữa sa mạc Sahara (Vietnamese, "Strange 'divine eye' in the Sahara"". Tiền Phong. 6 March 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- "The Lost City of Atlantis - Hidden in Plain Sight - Advanced Ancient Human Civilization". September 4, 2018 – via YouTube.

- Bartels, Meghan (July 13, 2016). "Scientists still have questions about the mysterious 'Eye of the Sahara'". Business Insider Australia.

- Donnelly, Ignatius L. (March 2003). The Atlantis Blueprint: Unlocking the Ancient Mysteries of a Long-Lost Civilization. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-3606-X.

- Schuchert, C (1917). "Atlantis and the Permanency of the North Atlantic Ocean Bottom". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 3 (2): 65–72. Bibcode:1917PNAS....3...65S. doi:10.1073/pnas.3.2.65. PMC 1091177. PMID 16586698.

- Ryall, J. C.; Blanchard, M.-C.; Medioli (1983). "A subsided island west of Flores, Azores". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 20 (5): 764–775. Bibcode:1983CaJES..20..764R. doi:10.1139/e83-068.

- Huang, T.C.; Watkins, N.D.; Wilson, L. (1979). "Deep-sea tephra from the Azores during the past 300,000 years: eruptive cloud height and ash volume estimates". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 90 (2): 131–133. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1979)90<131:DTFTAD>2.0.CO;2.

- Dennielou, B. G.A. Auffret, A. Boelaert, T. Richter, T. Garlan, and R. Kerbrat, 1999 Control of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the Gulf Stream over Quaternary sedimentation on the Azores Plateau. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série II. Sciences de la Terre et des Planetes. vol 328, no. 12, pp. 831-837.

- Azevedo, J.J.M.; Ferreira (1999). "Volcanic gaps and subaerial records of palaeo-sea-levels on Flores Island, Azores: tectonic and morphological implications" (PDF). Geodynamics. 17 (2): 117–129. Bibcode:1999JGeo...28..117A. doi:10.1016/S0264-3707(98)00032-5. hdl:10316/3946.

- Anthony Hildenbrand, Dominique Weis, Pedro Madureira, Fernando Ornelas Marques (December 2014). "Recent plate re-organization at the Azores Triple Junction". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Menendez, I.; Silva, P.G.; Martín-Betancor, M.; Perez-Torrado, F.J.; Guillou, H.; Scaillet, S. (2009). "Fluvial dissection, isostatic uplift, and geomorphological evolution of volcanic islands (Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain)". Geomorphology. 102 (1): 189–202. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.06.022.

- Perez-Torrado, J.F.; Santana, F.; Rodríguez-Santana, A.; Melian, A.M.; Lomostchitz, A.; Gimeno, D.; Cabrera, M.C.; Baez, M.C. (2002). "Reconstrucción paleogeográfica de los depósitos volcano-sedimentarios Pliocenos en el litoral NE de Gran Canaria (Islas Canarias) mediante métodos topográficos". Geogaceta. 32: 43–46.

- Meco, J.; Scaillet, S.; Guillou, H.; Lomoschitz, A.; Carracedo, J.C.; Ballester, J.; Betancort, J.-F.; Cilleros, A. (2007). "Evidence for long-term uplift on the Canary Islands from emergent Mio–Pliocene littoral deposits". Global and Planetary Change. 57 (3–4): 222–234. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2006.11.040. hdl:10553/17956.

- Zazo, C.; Goy, J.L.; Hillaire-Marcel, C.; Gillot, P.Y.; Soler, V.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Dabrio, C.J.; Ghaleb, B. (2002). "Raised marine sequences of Lanzarote and Fuerteventura revisited – a reappraisal of relative sea-level changes and vertical movements in the eastern Canary Islands during the Quaternary" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 21 (18–19): 2019–2046. doi:10.1016/s0277-3791(02)00009-4.

- Zazo, C.; Goy, J.L.; Dabrio, C.J.; Soler, V.; Hillaire-Marcel, CL.; Ghaleb, B.; Gonzalez-Delgado, J.A.; Bardajıf, T.; Cabero, A. (2007). "Quaternary marine terraces on Sal Island (Cape Verde archipelago)" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 26 (7–8): 876–893. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.12.014.

- Weaver, P.P.E., H.-U. Schmincke, J. V. Firth, and W. Duffield, eds., 1998, LEG 157—Scientific Results, Gran Canaria and Madeira Abyssal Plain Sites 950-956. Proceedings Ocean Drilling Project, Scientific Results. no. 157, College Station, Texas doi:10.2973/odp.proc.sr.157.1998

- Acosta, J.; Uchupi, E.; Munoz, A.; Herranz, P.; Palomo, C.; Ballesteros, M. (2003). "Geologic evolution of the Canarian Islands of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, Gran Canaria and La Gomera and comparison of landslides at these islands with those at Tenerife, La Palma and El Hierro". Marine Geophysical Researches. 24 (1–2): 1–40. doi:10.1007/s11001-004-1513-3. S2CID 129218101.

- "Cantabria cuna de la Humanidad", 1985. "Sant'Ander es Bizcaya, la fuente de la vida". "El verdadero origen de los vascos, la primera humanidad". "El origen cantábrico del homo sapiens". "El euskera madre del castellano" "Genealogical Tree Language"

- "(Investigaciones Jorge María Ribero-Meneses San José)". Iberia cuna de la humanidad. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- Viejo, G.F.; Suarez, J.G. (2005). "The ESCI-N Project after a decade: A synthesis of the results and open questions". Trabajos de Geología. 25: 9–25.

- Fugenschuh, B.; Froitzheim, N.; Capdevila, R.; Boillot, G. (2003). "Offshore granulites from the Bay of Biscay margins: fission tracks constrain a Proterozoic to Tertiary thermal history". Terra Nova. 15 (5): 337–342. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3121.2003.00502.x.

- Ercilla, G.; Casas, D.; Estrada, F.; Vázquez, J.T.; Iglesias, J.; García, M.; Gómez, M.; Acosta, J.; Gallart, J.; Maestro-González, A.; Team, Marconi (2008). "Morphsedimentary features and recent depositional architectural model of the Cantabrian continental margin". Marine Geology. 247 (1–2): 61–83. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2007.08.007.

- Hernandez-Molina, F.J.; Iglesias, J.; Rooij, D. Van; Ercilla, G.; Gómez-Ballesteros, M.; Casas, D.; Llave, E. (2008). "The Le Danois Contourite Depositional System: an exceptional record of the MOW circulation off the North Iberian margin". Geo-Tema. 10: 535–538.

- Dunbavin, Paul (June 2003). Atlantis of the West: The Case For Britain's Drowned Megalithic Civilization. Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-1145-0.

- Karl Shaw (2009). Curing Hiccups with Small Fires: A Delightful Miscellany of Great British ... p. 188. ISBN 9780752227030. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- "Russians seek Atlantis off Cornwall". BBC News. 1997-12-29. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- Erlingsson, Dr., Ulf (September 2004). Atlantis from a Geographer's Perspective. Lindorm Publishing. ISBN 0-9755946-0-5.

- Bernhard Weninger; et al. (2008). "The catastrophic final flooding of Doggerland by the Storegga Slide tsunami" (PDF). Documenta Praehistorica XXXV. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-10-11.

- Leake, Jonathan; Carpenter, Joanna (2007-09-02). "Britain's Atlantis under the North Sea". The Times. London. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- Spanuth, Jürgen (2000-11-01). Atlantis of the North. Scientists of New Atlantis. ISBN 1-57179-078-0.

- Gerhard Herm The Celts: The People Who Came Out of the Darkness Book Club Associates, London 1975

- Bock, Ior. "Atlantis rising magazine". bocksaga.com. Archived from the original on 2006-10-05. See also: Bock, Ior. Bockin perheen saaga. Helsinki 1996. ISBN 952-5137-00-7

- Joseph, Frank (2008). The Atlantis Encyclopedia. Red Wheel/Weiser. ISBN 9781632657916.

- Jerkert (red), Jesper (2007). Fakta eller fantasier: föreställningar i vetenskapens gränstrakter (in Swedish). Leopard Förlag. ISBN 9789173432115.

- Gómara, Francisco López de, Historia de las Indias (Hispania Victrix; First and Second Parts of the General History of the Indies, with the whole discovery and notable things that have happened since they were acquired until the year 1551, with the conquest of Mexico and New Spain), Zaragoza 1552

- Zárate, Agustín de, Historia del descubrimiento y conquista del Perú (1556) published in English as The Discovery and History of Peru trans by J.M. Cohen, Pub Penguin Classics 1968

- Gamboa, Pedro Sarmiento de Historia de los Incas. (History of the Incas) Peru 1572 and Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1943. trans. by Clements Markham, (1907) as History of the Incas, UK, The Hakluyt Society, Cambridge University Press

- Sebastian Münster (1540). "munster map new world".

- "Atlantis Insula, à Nicolao Sanson Antiquitati Restituta". John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.

- The Atlantis Blueprint: Unlocking the Ancient Mysteries of a Long-Lost Civilization. Delta; Reprint edition. May 28, 2002. ISBN 0-440-50898-3.

- Earth's shifting crust: A key to some basic problems of earth science. Pantheon Books. 1958. ASIN B0006AVEEU.

- "Paradise Found: Index of Subjects". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- "Paradise Found: Part Fourth: Chapter I. Ancient Cosmology and Mythical Geography". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

Further reading

General information

- Vidal-Naquet, P (2007). The Atlantis Story: A Short History of Plato's Myth. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0859898058

- Ramage, ES (1978). Atlantis, Fact or Fiction?. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253104823

- Atlantis Conference Milos 2005 Proceedings of the International Conference "The Atlantis Hypothesis: Searching for a Lost Land" , Athen 2007 ISBN 978-960-89882-1-7

- Atlantis Conference Athens 2008 Proceedings of the International Conference "The Atlantis Hypothesis: Searching for a Lost Land" , Athen 2010 ISBN 978-960-6746-10-9

- NatGeo - Further

Specific hypotheses

- Allen, JM (1998). Atlantis: the Andes Solution.

- Allen, JM (2000). The Atlantis Trail, 2000. Kindle 2010.

- Allen, JM (2009). Atlantis: Lost Kingdom of the Andes, Floris Books.

- Andrews, S (2002). Atlantis. Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 1-56718-023-X

- Berlitz, C (1974). The Bermuda Triangle. 1974. ISBN 978-0385041140

- Brandenstein, W (1951). Atlantis – Größe und Untergang eines geheimnisvollen Inselreiches, Gerold & Co Vienna.

- Donnelly, I (1882). Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, New York: Harper & Bros. Retrieved 6 November 2001, from Project Gutenberg.

- Collina-Girard, J (2009). L'Atlantide Rétrouvée? Enquête scientifique autour d'un mythe, Belin-Pour la Science éditeur, Collection Regards. ISSN 1773-8016, ISBN 978-2-7011-4608-9

- Collina-Girard, J (2001). L'Atlantide devant le Detroit de Gibraltar ? mythe et géologie. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des Planètes. 333; 233-240.

- Díaz-Montexano, G (2012). Atlantis - Tartessos. Aegyptius Codex. Epítome de la Atlántida Histórico-Científica. Una confederación talasocrática Íbero-Líbica y Hykso-minoica. Un estudio de la Atlántida -a modo de exordio- desde las fuentes documentales primarias y secundarias. Tomo I. Con prólogo de los doctores Cesar Guarde y Antonio Morillas de la Universidad de Barcelona. Turpin Ediciones S.L (Madrid). ISBNdb.com - Book Info ISBN 1-4610-1958-3 / ISBN 978-1-4610-1958-9. (Spanish)

- Donnelly, I (1882). Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. New York, Harper. LCCN 06001749

- Dunbavin P (2003). Atlantis of the West: The Case For Britain's Drowned Megalithic Civilization. ISBN 0-7867-1145-0

- Erlingsson, U (2004). Atlantis from a Geographer's Perspective: Mapping the Fairy Land. Lindorm Publishing. ISBN 0-9755946-0-5

- Flem-Ath, R&R (1995). When The Sky Fell. ISBN 978-0312136208

- Flem-Ath, R & Wilson, C (2000). The Atlantis Blueprint.

- Franke, TC (2012). Aristotle and Atlantis - What did the philosopher really think about Plato's island empire?, Bod Norderstedt/Germany. German edition 2010. ISBN 978-3848227914

- Frau, S (2002). Le Colonne d'Ercole: Un'inchiesta, Rome: Nur neon. ISBN 88-900740-0-0

- Galanopoulos, AG & Bacon E (1969). Atlantis; the truth behind the legend. Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill. LCCN 71080738 //r892

- Ashe, G (1992). Atlantis : lost lands, ancient wisdom / Geoffrey Ashe. New York, N.Y., Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-81039-7

- Görgemanns, H (2000). Wahrheit und Fiktion in Platons Atlantis-Erzählung, Hermes, vol. 128, pp. 405–420.

- Joseph, F (2002). The Destruction of Atlantis: Compelling Evidence of the Sudden Fall of the Legendary Civilization. Bear & Company. ISBN 1-879181-85-1

- King, D. (1970). Finding Atlantis: A true story of genius, madness, and an extraordinary quest for a lost world. Harmony Books, New York. ISBN 1-4000-4752-8

- Ley, W (1969). Another look at Atlantis, and fifteen other essays. Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday. LCCN 69011988

- Luce JV (1978): The Literary Perspective – The Sources and Literary Form of Plato's Atlantis Narrative, in: Edwin S. Ramage (ed.), Atlantis – Fact or Fiction? 49-78. ISBN 978-0253104823

- Luce JV (1982). End of Atlantis: New Light on an Old Legend, Efstathiadis Group: Greece

- Mifsud, A&S, Sultana CA, Ventura CS (2001). Echoes of Plato's Island. (2nd edition) Malta. ISBN 99932-15-01-5

- Muck, OH (1976/1978). The Secret of Atlantis, Translation by Fred Bradley of Alles über Atlantis (Econ Verlag GmbH, Düsseldorf-Wien), Times Books, a division of Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co., Inc., Three Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016. ISBN 978-0671823924

- Spence, L (1924) The Problem of Atlantis, London.

- Spence, L (1926/2003). The History of Atlantis, Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-42710-2

- Zangger, E (1992). The Flood from Heaven: Deciphering the Atlantis legend. Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-688-11350-8

- Zeilinga de Boer, J et al. (2002). Volcanoes in human history : the far-reaching effects of major eruptions. The Bronze Age eruption of Thera : destroyer of Atlantis and Minoan Crete?. Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press.

- Zhirov, NF (1970). Atlantis – Atlantology: Basic Problems, Translated from the Russian by David Skvirsky, Progress Publishers, Moscow.

External links

General information

- International Conference Atlantis 2005 , Milos/Greece

- International Conference Atlantis 2008 , Athens/Greece

- International Conference Atlantis 2011 , Santorini/Greece

- Atlantipedia.ie

- Atlantis-Scout: Systematic Weblink Collection on Plato's Atlantis

- The Mysterious City of Atlantis Discovery Channel Documentary

- Naked Science - Atlantis