Lord's Resistance Army

The Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), also known as the Lord's Resistance Movement, is a rebel group and heterodox Christian group which operates in northern Uganda, South Sudan, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[10] Originally known as the United Holy Salvation Army and Uganda Christian Army/Movement, its stated goals include establishment of multi-party democracy,[11] ruling Uganda according to the Ten Commandments,[12] and Acholi nationalism.[13]

| Lord's Resistance Army | |

|---|---|

Though the red-black-blue flag has been widely attributed to the Lord's Resistance Army,[1] the group also uses the regular flag of Uganda.[2] | |

| Leaders |

|

| Dates of operation | 1987–present |

| Headquarters | Believed to be South Sudan or Central African Republic (2014) |

| Active regions | |

| Size | |

| Allies | |

| Opponents | |

In practice "the LRA is not motivated by any identifiable political agenda, and its military strategy and tactics reflect this".[14] It appears to largely function as a personality cult of its leader Joseph Kony,[13] a self-declared prophet whose leadership has earned him the nickname "Africa's David Koresh".[15]

The LRA was listed as a terrorist group by the United States,[16] though it has since been removed from the list of designated active terrorist groups. It has been accused of widespread human rights violations, including murder, abduction, mutilation, child-sex slavery, and forcing children to participate in hostilities.[17][18]

History

| Lord's Resistance Army insurgency |

|---|

|

| Conflict history |

| Related articles |

Bantu-speaking agriculturists such as the Baganda people in Uganda's south and east developed different and competing for social and economic structures from the Nilotic language speaking Acholi in the north, whose economic system was centred around hunting, farming and livestock herding.[19] The ethnic and cultural divisions within Uganda continued to exist during the years of the British Uganda Protectorate, which was created in 1894. While the agricultural Baganda people worked closely with the British, the Acholi and other northern ethnic groups supplied much of the national manual labour and came to comprise a majority of the military.[20]

The southern region became the centre for commercial trade development.[21] The livestock-raising Acholi from the north of Uganda were resented for dominating the army and policing. Following the country's independence in 1962, Uganda's ethnic groups continued to compete with each other within the bounds of Uganda's new political system.

In 1986, the armed rebellion led by Yoweri Museveni's National Resistance Army (NRA) won the Ugandan Bush War and took control of the country. The victors sought vengeance against ethnic groups in the North of Uganda. Their activities included Operation Simsim, which engaged in burning, looting, and killings of locals.

Such acts of violence led to the formation of rebel groups from the ranks of the previous Ugandan army, UNLA. Many of those groups made peace with Museveni. However, the southern-dominated army did not stop attacking civilians in the north of the country. Therefore, by late 1987 to early 1988, a civilian resistance movement led by Alice Lakwena was formed.

Lakwena did not pick up arms against the central government; her members carried sticks and stones. She believed she was inspired by the Holy Spirit of God. Lakwena portrayed herself as a prophet who received messages from the Holy Spirit and expressed the belief that the Acholi could defeat the Museveni government. She preached that her followers should cover their bodies with shea nut oil as protection from bullets, never take cover or retreat in battle, and never kill snakes or bees.[22]

Joseph Kony would later preach a similar superstition, encouraging soldiers to use oil to draw a cross on their chest as protection from bullets. During a later interview, however, Alice Lakwena distanced herself from Kony, claiming that the Spirit does not want soldiers to kill civilians or prisoners of war.

Kony sought to align himself with Lakwena and, in turn garner support from her constituents, even going so far as to claim they were cousins.[23] Meanwhile, Kony gained a reputation as having been possessed by spirits and became a spiritual figure or a medium. He and a small group of followers first moved beyond his home village of Odek on 1 April 1987.[24] A few days later, he met a group of former Uganda National Liberation Front soldiers from the Black Battalion whom he managed to recruit.[24] They then launched a raid on the city of Gulu.[24]

By August 1987, Lakwena's Holy Spirit Mobile Force scored several victories on the battlefield and began a march towards the capital Kampala. In 1988, after the Holy Spirit Movement was decisively defeated in the Jinja District and Lakwena fled to Kenya, Kony seized this opportunity to recruit the Holy Spirit remnants. The LRA occasionally carried out local attacks to underline the inability of the government to protect the population. The fact that most National Resistance Army (NRA) government forces, in particular, former members of the Federal Democratic Movement (FEDEMO),[25] were known for their lack of discipline and brutal actions meant that the civilian population was accused of supporting the rebel LRA; likewise, the rebels accused the population of supporting the government army.[26]

In March 1991, the Ugandan government's NRA started Operation North, which combined efforts to destroy the LRA, while cutting away its roots of support among the population through heavy-handed tactics.[27] As part of Operation North, the army created the "Arrow Groups", village guards mostly armed with bows and arrows. The creation of the Arrow Groups angered Kony, who began to feel that he no longer had the support of the population. After the failure of Operation North, Betty Bigombe initiated the first face-to-face meeting between representatives of the rebel LRA and NRA government. The rebels asked for a general amnesty for their combatants and to "return home", but the government stance was hampered by disagreement over the credibility of the LRA negotiators and political infighting.[26] At a meeting in January 1994, Kony asked for six months to regroup his troops, but by early February the tone of the negotiations was growing increasingly acrimonious and the LRA broke off negotiations, accusing the government of trying to entrap them.[26]

Starting in the mid-1990s, the LRA was strengthened by military support from the government of Sudan,[28] which was retaliating against Ugandan government support for rebels in what would become South Sudan. The LRA fought with the NRA army which led to mass atrocities such as the killing or abduction of several hundred villagers in Atiak in 1995 and the kidnapping of 139 schoolgirls in Aboke in 1996. The government created the so-called "protected camps" beginning in 1996. The LRA declared a short-lived ceasefire for the duration of 1996 Ugandan presidential election, possibly in the hope that Yoweri Museveni would be defeated.[29]

In March 2002, the NRA, under the new name of the Uganda People's Defence Force (UPDF), launched a massive military offensive code-named Operation Iron Fist against the LRA bases in southern Sudan, with agreement from the National Islamic Front. In retaliation, the LRA attacked the refugee camps in northern Uganda and the Eastern Equatoria in southern Sudan, brutally killing hundreds of civilians.[25][30][31][32]

By 2004, according to the UPDF spokesman Shaban Bantariza, mediation efforts by the Carter Center and the Pope John Paul II had been spurned by Kony.[33] In February 2004, the LRA unit led by Okot Odhiambo attacked Barlonyo IDP camp, killing over 300 people and abducting many others.[25][34]

In 2006, UNICEF estimated that the LRA had abducted at least 25,000 children since the conflict began.[35] In January 2006, eight Guatemalan Kaibiles commandos and at least 15 rebels were killed in a botched UN special forces raid targeting the LRA deputy leader Vincent Otti in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[36]

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the LRA attacks and the government's counter-insurgency measures have resulted in the displacement of nearly 95 percent of the Acholi population in three districts of northern Uganda. By 2006, 1.7 million people lived in more than 200 internally displaced person (IDP) camps in northern Uganda.[35] These camps had some of the highest mortality rates in the world. The Ugandan Ministry of Health and partners estimated that through the first seven months of 2005, about 1,000 people were dying weekly, chiefly from malaria and AIDS. During the same time period of January–July 2005, the LRA abducted 1,286 Ugandans (46.4 percent of whom were children under the age of 15 years), and violence accounted for 9.4 percent of the 28,283 deaths, occurring mostly outside camps.[37]

In 2006–2008, a series of meetings were held in Juba, Sudan, between the government of Uganda and the LRA, mediated by the south Sudanese separatist leader Riek Machar. The Ugandan government and the LRA signed a truce on 26 August 2006. Under the terms of the agreement, LRA forces would leave Uganda and gather in two assembly areas in the remote Garamba National Park area of northern Democratic Republic of Congo that the Ugandan government agreed not to attack.[38]

Between December 2008 – March 2009, the armed forces of Uganda, DR Congo and South Sudan launched aerial attacks and raids on the LRA camps in Garamba, destroying them. The efforts to inflict a military defeat on the LRA were not fully successful. The U.S.-supported Operation Lightning Thunder against the LRA. There were brutal revenge attacks by scattered LRA remnants, with over 1,000 people killed and hundreds abducted in Congo and South Sudan. Hundreds of thousands were displaced while fleeing the massacres. The military action in the DRC did not result in the capture or killing of Kony, who remained elusive.[38]

During the Christmas of 2008, the LRA massacred at least 143 people and abducted 180 at a concert celebration sponsored by the Catholic Church in Faradje in the Democratic Republic of Congo.[39] The LRA struck several other communities in the near-simultaneous attacks: 75 people were murdered in a church near Dungu, at least 80 were killed in Batande, 48 in Bangadi, and 213 in Gurba.[40][41][42]

By August 2009, the LRA terror in the DRC resulted in displacing as many as 320,000 Congolese, exposing them to a threat of famine, according to UNICEF director Ann Veneman.[43] Also in August 2009, the LRA attacked a Catholic church in Ezo, South Sudan, on the Feast of the Assumption, with reports of victims being crucified, causing Ugandan Archbishop John Baptist Odama to call on the international community for help in finding a peaceful solution to the crisis.[44][45][46]

In December 2009, the LRA forces under Dominic Ongwen killed at least 321 civilians and abducted 250 others during a four-day rampage in the village and region of Makombo in the DR Congo.[25][47] In February 2010, about 100 people were massacred by the LRA in Kpanga, near DR Congo's border with the Central African Republic and Sudan.[48] Small-scale attacks continued daily, displacing large numbers of people and worsening an ongoing humanitarian crisis which the UN described as one of the worst in the world.[49]

By May 2010, the LRA killed over 1,600 Congolese civilians and abducted more than 2,500.[50] Between September 2008 and July 2011, the group, despite being down to only a few hundred fighters, has killed more than 2,300 people, abducted more than 3,000, and displaced over 400,000 across the DR Congo, South Sudan and the Central African Republic.[51]

In March 2012, Uganda announced it would head a new four-nation African Union military force (a brigade of 5,000, including contingents from the DR Congo, Central African Republic and South Sudan) to hunt down Kony and the remnants of the LRA, but asked for more international assistance for the task force.[52][53] In 2012 the LRA was reported to be in Djema, Central African Republic[54] but forces pursuing the LRA withdrew in April 2013[55] after the government of the Central African Republic was overthrown by the Séléka Coalition rebels.[56]

Causes of the LRA conflict

Ethnicity, stereotypes, hate, and enemy images

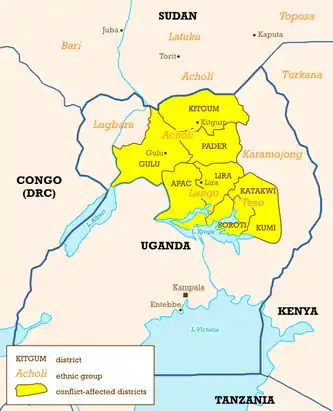

Part of the structural causes of the LRA conflict has been explained as rooted in the "diversity of ethnic groups which were at different levels of socio-economic development and political organization".[57] This has led to ethnic strife. Enemy images have instilled insensitivity to the extent that people perceived as enemies can be construed and ignored as inconsequential. A former Cabinet minister who was a key figure in the Presidential Peace Team while addressing elders in Lango on the atrocities committed by the NRA in the northern districts of Gulu, Kitgum, Lira, Apac and Teso, warned them that "they did not matter as long as the south was stable". This sense of betrayal on the northerners has festered into a groundswell of mistrust by the population against virtually any overtures from the government to the rebels.

This cynical strategy, some argue, was deeply rooted and employed in Luwero triangle by the NRM/A rebels during their five-year-bush war in order to garner popular support, while in essence, their real underlying drive was "unique greed for absolute political power" in total abhorrence of democratic means.[58]

Economic disparity (and/or marginalisation), underdevelopment and poverty

The strong imbalance in the level of development and investment between Eastern & Northern Uganda on the one side, and Central & Western Uganda on the other perceived as the land of milk and honey, is a clear manifestation of economic marginalisation of the region, in spite of the fact that most top leadership in Uganda hailed from the north between 1962 and 1985. This marginalisation, deliberate or otherwise, with the adverse consequences of the war, has resulted in disparate poverty levels in northern Uganda, for the most part of the NRM's 20 plus years’ rule. Although poverty at times may be treated as an escalating factor that creates resentment in society, its role in the conflict in northern Uganda is part and parcel of the underlying structural factors. The Poverty Status Report, 2003, indicates that "one-third of the chronically poor (30.1%) and a disproportionate moving into poverty are from northern Uganda".[59]

Contributing factors

The LRA is a consequence of an ethnic-oriented war that was initiated by the NRM/A in Luwero Triangle against the ‘northerners’. This was fuelled by the belief on the part of the leadership of the NRM/A that Uganda politics had since political independence been ‘dominated’ by the ‘northerners’ in the country and that this had happened because of their alleged domination of the armed forces. The determination was that this ‘domination’ of politics in Uganda by the ‘northerners’ was no longer acceptable and had to end. This suggested that until that objective of removing the ‘northerners’ from power had been achieved and all threats from those quarters removed, the war in the north had to continue.[60]

Ideology

The LRA's ideology is disputed among academics.[33][61] Although the LRA has been regarded primarily as a Christian militia,[62][63][64][65][66][67] the LRA reportedly evokes Acholi nationalism on occasion,[68] but many observers doubt the sincerity of this behaviour and the loyalty of Kony to either ideology.[69][70][71][72][73]

Robert Gersony, in a report funded by United States Embassy in Kampala in 1997, concluded that "the LRA has no political program or ideology, at least none that the local population has heard or can understand."[74] The International Crisis Group has stated that "the LRA is not motivated by any identifiable political agenda, and its military strategy and tactics reflect this."[14]

IRIN comments that "the LRA remains one of the least understood rebel movements in the world, and its ideology, as far as it has one, is difficult to understand."[33] During an interview with IRIN, the LRA commander Vincent Otti was asked about the LRA's vision of an ideal government, to which he responded:

Lord's Resistance Army is just the name of the movement because we are fighting in the name of God. God is the one helping us in the bush. That's why we created this name, Lord's Resistance Army. And people always ask us, are we fighting for the Ten Commandments of God. That is true – because the Ten Commandments of God is the constitution that God has given to the people of the world. All people. If you go to the constitution, nobody will accept people who steal, nobody could accept to go and take somebody's wife, nobody could accept to kill the innocent, or whatever. The Ten Commandments carries all this.

In a speech delivered by James Alfred Obita, former secretary for external affairs and mobilisation of the Lord's Resistance Army, he adamantly denied that the LRA was "just an Acholi thing" and stated that claims made by the media and Museveni administration asserting that the LRA is a "group of Christian fundamentalists with bizarre beliefs whose aim is to topple the Museveni regime and replace it with governance based on the Bible's ten commandments" were false.[11] In the same speech, Obita also claimed that the LRA's objectives are:

- To fight for the immediate restoration of competitive multi-party democracy in Uganda.

- To see an end to gross violation of human rights and dignity of Ugandans.

- To ensure the restoration of peace and security in Uganda.

- To ensure unity, sovereignty, and economic prosperity beneficial to all Ugandans.

- To bring to an end to the repressive policy of deliberate marginalization of groups of people who may not agree with the National Resistance Army's ideology.

The original aims of the group were more closely aligned with those of its predecessor, the Holy Spirit Movement. Protection of the Acholi population was of great concern because of the reality of ethnic purges in the history of Uganda.[75] This created a great deal of concern in the Acholi community as well as a strong desire for formidable leadership and protection.[75] As the conflict has progressed, fewer and fewer Acholi offered sufficient support to the rebels in the eyes of the LRA.[76] This led to an increased amount of violence toward the non-combatant population, which in turn further alienated them from the rebels.[76] This self-perpetuating cycle led to the creation of a strict divide between Acholis and rebels, a divide that was previously not explicitly present.

Strength

In 2007, the government of Uganda claimed that the LRA had only 500 or 1,000 soldiers in total, but other sources estimated that there could have been as many as 3,000 soldiers, along with about 1,500 women and children.[3] By 2011, unofficial estimates were in the range of 300 to 400 combatants, with more than half believed to be abductees.[4] The soldiers are organized into independent squads of 10 or 20 soldiers.[3]

By early 2012, the LRA had been reduced to a force of between 200 and 250 fighters, according to Ugandan defence minister Crispus Kiyonga.[52] Abou Moussa, the UN envoy in the region, said in March 2012 that the LRA was believed to have dwindled to between 200 and 700 followers but still remained a threat: "The most important thing is that no matter how little the LRA may be, it still constitutes a danger [as] they continue to attack and create havoc."[53]

Since the LRA first started fighting in the 1990s they may have forced well over 10,000 boys and girls into combat, often killing family, neighbors and school teachers in the process.[77] Many of these children were put on the front lines so the casualty rate for these children has been high. The LRA have often used children to fight because they are easy to replace by raiding schools or villages.[78] According to Livingstone Sewanyana, executive director of the Foundation for Human Rights Initiative, the government was the first to use child soldiers in this conflict.[79]

Although this is not proven, there has been rumors that Sudan may have provided military assistance to the LRA, in response to Uganda lending military support to the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA).[80][81] According to Matthew Green, author of The Wizard of the Nile: The Hunt for Africa’s Most Wanted, the LRA was highly organised and equipped with crew-operated weapons, VHF radios and satellite phones.[82] In 2001, it was also reported that LRA targets Sudanese refugees.[83]

ICC investigation

The International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants on 8 July and 27 September 2005, against Joseph Kony, his deputy Vincent Otti, and the LRA commanders Okot Odhiambo, deputy army commander and Dominic Ongwen, brigade commander of the Sania Brigade of the LRA. The four LRA leaders were charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes, including murder, rape, and sexual slavery. Ongwen was the only of the four not charged with recruiting child soldiers. The warrants were filed under seal; public redacted versions were released on 13 October 2005.[84]

These were the first warrants issued by the ICC since it was established in 2002. Details of the warrants were sent to the three countries where the LRA is active: Uganda, Sudan (the LRA was active in what is now South Sudan), and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The LRA leadership has long stated that they would never surrender unless they were granted immunity from prosecution; so the ICC order to arrest them raised concerns that the insurgency would not have a negotiated end.[85]

The indictments received warm praise within the international community. However, the Acholi people showed mixed reactions. Many felt that amnesty for the LRA soldiers and a negotiated settlement was the best hope for the end of the war. In the end, the court's intent to prosecute the leaders of the LRA reduced the army's willingness to cooperate in peace negotiations.

On 30 November 2005, the LRA deputy commander, Vincent Otti, contacted the BBC announcing a renewed desire among the LRA leadership to hold peace talks with the Ugandan government. The government expressed skepticism regarding the overture but stated their openness to a peaceful resolution of the conflict.[86]

On 2 June 2006, Interpol issued five wanted person red notices to 184 countries on behalf of the ICC, which has no police of its own. Kony had been previously reported to have met Vice President of South Sudan Riek Machar.[87][88] The next day, Human Rights Watch reported that the regional government of Southern Sudan had ignored previous ICC warrants for the arrest of four of LRA's top leaders, and instead supplied the LRA with cash and food as an incentive to stop them from attacking southern Sudanese citizens.[89]

At least two of the five wanted LRA leaders have since been killed: Lukwiya in August 2006[90] and Otti in late 2007 (executed by Kony).[91] Odhiambo was rumoured to have been killed in April 2008.[92] In February, 2015, UPDF forces found the body of an unidentified person. Later on in April, DNA tests identified that the body was that of Odhiambo.

In July 2011, South Sudan seceded from Sudan, cutting the LRA off geopolitically from its former allies in Khartoum.

In January 2015, Dominic Ongwen was reported either to have defected or to have been captured and was held by the Ugandan forces.[93][94]

Foreign involvement

In late 2013, Ugandan forces, alerted by U.S. troops, killed chief planner Colonel Samuel Kangul, amongst others.[95]

United States

The United States provides support for military efforts, notably by the UPDF against the LRA.[96] Some observers have reported that the United States is involved for reasons other than the LRA.[97]

After the 11 September attacks, the United States declared the Lord's Resistance Army to be a terrorist group.[16] On 28 August 2008, the United States Department of State sanctioned Joseph Kony as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist under Executive Order 13224 "Specially Designated Global Terrorists", a designation that carries financial and other penalties.[98]

In November 2008, U.S. President George W. Bush personally signed a directive to the United States Africa Command to provide assistance financially and logistically to the Ugandan government during the unsuccessful Garamba Offensive, code-named Operation Lightning Thunder.[99] No U.S. troops were directly involved, but 17 U.S. advisers and analysts provided intelligence, equipment, and fuel to Ugandan military counterparts.[99] The offensive pushed Kony from his jungle camp, but he was not captured. One hundred children were rescued.[99]

In May 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama signed into law the Lord's Resistance Army Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act,[100] legislation aimed at stopping Joseph Kony and the LRA. The bill passed unanimously in the Senate on 11 March 2010, with 65 senators as cosponsors, then passed unanimously in the House of Representatives on 13 May 2010, with 202 representatives as cosponsors. On 24 November 2010, Obama delivered a strategy document to the U.S. Congress, asking for money to disarm Kony and the LRA.[101]

On 14 October 2011, Obama announced that he had ordered the deployment of 100 U.S. military advisors with a mandate to train, assist and provide intelligence to help combat the Lord's Resistance Army,[102] reportedly from the Army Special Forces,[102][103] at a cost of approximately $4.5 million per month.[104] Human Rights Watch welcomed the deployment, which they had previously advocated for,[105][106] and Obama said that the deployment did not need explicit approval from the U.S. Congress, as the 2010 Lord's Resistance Army Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act already authorised "increased, comprehensive U.S. efforts to help mitigate and eliminate the threat posed by the LRA to civilians and regional stability". The military advisors will be armed, and will provide assistance and advice, but "will not themselves engage LRA forces unless necessary for self-defense."[107]

Two members of the United States Special Operations effort in Operation Observant Compass (OOC), Mick Mulroy and Eric Oehlerich, made a documentary about a child soldier who escaped from the LRA and went on to help end it. The documentary's name is "My Star in the Sky" and had been screened at numerous universities and think tanks for the benefit of nonprofits helping to end the use of children as soldiers.[108][109][110][111] Foreign Policy reports that Mulroy called OOC, a “model” for how to address child soldiers using influence operations instead of lethal force. They worked with NGOs who found mothers of child soldiers and had them broadcast messages over the radio, begging them to come home. Mulroy said that a lot of these kids didn't think they were going to be allowed back, so to have their mother get on the radio and specifically tell them ‘we want you back’ made a big difference. He continued that other missions are driven by the kinetics—this was not. Marine Corps Col. Jon Darren Duke, who previously commanded OOC, said they did everything they could to get the child soldiers to defect so they would not have to fight them by using psychological operations to “appeal to them to lay down their arms,” he said at one screening.[111] Mulroy said that he hopes that OOC serves as a model for future programs to address child soldiers, as well as other operations as it showed how the U.S. military can use “soft power, influence operations” and other aspects of so-called “irregular warfare” to fight the problem.[111]

African Union

On 18 September 2012, the African Union launched an initiative in Nzara, South Sudan to take control of the fight against the LRA. The goal of the project was to co-ordinate efforts against the group by the ongoing operations conducted by the states of Uganda, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Central African Republic. However, some fear that these armies are looting resources in the region. The civilians have reported rapes, killings and lootings by the Ugandan army.[112]

At a ceremony to mark the handover of command in Yambio, the AU's special envoy on the LRA, Francisco Madeira, said that while the Congo DR had not sent supporting troops, it had made some other unnamed support. "We need more support, I don't have to elaborate on these because my predecessor has done this so well. We need support in terms of means of transport, communication, medicine, combat rations and uniforms for the troops tracking the LRA. This is particularly important and critical and most urgent for the central African troops who handed over their contingent despite the challenges facing them."[113]

Ugandan Defence Minister Chrispus Kiyonga said: "We are yet to fully agree on how this troops will operate because now they are going to be one force, a regional task force with its commander. There are two concepts: There are people who think that the SPLA [Sudan People Liberation Army] should only work on the side of Sudan, that the army of the Central African Republic should only work there [within its own borders]...but there is the other concept that some of us support, [which is] that once there is one unified force, co-ordinated force then it should go wherever Kony is. We think that way, it will be more effective." He added that the newest intelligence reports at the time has suggested the LRA then had only 200 guns and numbered about 500 people, including women and children.[113]

In popular culture

- In the 2006 movie Casino Royale, a high-ranking member of the Lord's Resistance Army entrusts Le Chiffre and gives him a large sum of money to invest.

- The movie Machine Gun Preacher is a 2011 biographical drama that describes the life of Sam Childers and his efforts to save the children of South Sudan with the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) against the atrocities of the Lord's Resistance Army.

- A 2017 film Kony: Order from Above, is also set during this war.

See also

References

- "Lord's Resistance Army (LRA)". Sudan Tribune. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- Ledio Cakaj (13 April 2010). "On LRA Uniforms". Enough Project. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- IRIN (2 June 2007). UGAND-SUDAN: Ri-Kwangba: meeting point Archived 16 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- Le Sage, Andre (July 2011). "Countering the Lord's Resistance Army in Central Africa" (PDF). Strategic Forum. Institute for National Strategic Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- Baddorf, Zack (20 April 2017). "Uganda Ends Its Hunt for Joseph Kony Empty-Handed". Nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- "The Lord's Resistance Army". Warchild.org.uk. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- "The Lord's Resistance Army in Sudan: A History and Overview" (PDF). Smallarmssurveysudan.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- "Guatemalan blue helmet deaths stir Congo debate". Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- "US troops to help Uganda fight rebels". Al Jazeera English. 4 October 2011. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- "Terrorist Organization Profile: Lord's Resistance Army (LRA)". National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, University of Maryland. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- Obita, James. "The Official presentation of the Lord's Resistance Movement/Army (LRA/M)". A Case for National Reconciliation, Peace, Democracy and Economic Prosperity for All Ugandans. Kacoke Madit. Archived from the original on 31 March 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- "Profile: The Lord's Resistance Army". aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- Julian Borger (8 March 2012). "Q&A: Joseph Kony and the Lord's Resistance Army". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- "Northern Uganda: Understanding and solving the conflict" (PDF). ICG Africa Report N°77. Nairobi/Brussels: International Crisis Group. 14 April 2004. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- Drogin, Bob. "Cult Killing, Ravaging in New Uganda". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Philip T. Reeker (6 December 2001). "Statement on the Designation of 39 Organizations on the USA PATRIOT Act's Terrorist Exclusion List". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- International Criminal Court (14 October 2005). Warrant of Arrest unsealed against five LRA Commanders. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- Richard Dowden. "Court threatens to block cannibal cult's peace offer". Royal African Society. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- Rita M. Byrnes, ed. Uganda: A Country Study Archived 3 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1990. p. 4

- Alfred G. Nhema, "The resolution of African conflicts: the management of conflict resolution & post-conflict reconstruction." p.53. Ohio University Press, 2008

- Dolan, Chris, "Social Torture: The Case of Northern Uganda, 1986–2006", 2009, New York: Berghahn Books, p.41

- Briggs, Jimmie, Innocents Lost: When Child Soldiers Go to War, 2005, p. 113.

- Van Acker, Frank, "Uganda and The Lord's Resistance Army: The New Order No One Ordered," 2004, African Affairs 103(412), p.345

- Green, Matthew (2008). The Wizard of the Nile: The Hunt for Africa's Most Wanted. Portobello Books. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-1-84627-031-4.

- Plaut, Martin (28 March 2010). "DR Congo rebel massacre of hundreds is uncovered". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- O’Kadameri, Billie. "LRA / Government negotiations 1993–94" Archived 21 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine in Okello Lucima, ed., Accord magazine: Protracted conflict, elusive peace: Initiatives to end the violence in northern Uganda Archived 6 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 2002.

- Gersony, Robert. The Anguish of Northern Uganda: Results of a Field-based Assessment of the Civil Conflicts in Northern Uganda Archived 17 November 2004 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), US Embassy Kampala, March 1997, and Amnesty International, Human rights violations by the National Resistance Army Archived 17 November 2004 at the Wayback Machine, December 1991.

- Elizabeth Dickinson. "WikiFailed States". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- Green, Matthew (2008). The Wizard of the Nile: The Hunt for Africa's Most Wanted. Portobello Books. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-84627-031-4.

- Frank Nyakairu. "Uganda: Joseph Kony's Killing Fields in Northern Region". Liu Institute for Global Issues. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- James Kilford (29 April 2002). "Enforced Ugandan cannibalism". eTravel.org. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- START. "Terrorist Organization Profile: Lord's Resistance Army (LRA)". START. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- "UGANDA: Nature, structure and ideology of the LRA". IRIN. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- "Killing Every Living Thing: Barlonyo Massacre". Scribd.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Uganda Complex emergency Situation Report #3 09/13/2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- Reuters – AlertNet (31 January 2006). "Democratic Republic of the Congo (the): Guatemalan blue helmet deaths stir Congo debate | ReliefWeb". Reliefweb.int. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "IRIN Africa | UGANDA: 1,000 displaced die every week in war-torn north – report | Uganda | Refugees/IDPs". Irinnews.org. 29 August 2005. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Uganda to continue Congo LRA hunt". BBC. 5 March 2009. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

- Human Rights Watch (17 January 2009). DR Congo: LRA Slaughters 620 in 'Christmas Massacres’ Archived 28 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- BBC News (29 December 2008). Ugandan LRA 'in church massacre' Archived 30 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Mukasa, Henry (30 December 2008). "Uganda: Kony Rebels Kill 400 Congo Villagers". allAfrica.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- CNN (30 December 2008). "Congo groups: 400 massacred on Christmas day Archived 14 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved on 4 January 2009.

- Owen Bowcott (31 August 2009). "Ugandan rebels have displaced as many as 320,000 people in northern Democratic Republic of Congo, Unicef chief says". London: Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Christians are 'crucified' in guerrilla raids". Catholic Herald. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- "Sudanese bishop urges peace talks with Lord's Resistance Army". Catholic Herald. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- "LRA: Ugandan bishop urges negotiated settlement". BBC. 19 January 2011. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- Anneke Van Woudenberg, senior Africa researcher (28 March 2010). "DR Congo: Lord's Resistance Army Rampage Kills 321 | Human Rights Watch". Hrw.org. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- Fessy, Thomas (2 May 2010). "'Fresh LRA massacre' in DR Congo". BBC News.

- "LRA rebels killed 26 in DR Congo in June: UN | Radio Netherlands Worldwide". Rnw.nl. 6 July 2011. Archived from the original on 7 April 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- Associated Press in Niangara (2 May 2010). "Lord's Resistance Army massacres up to 100 in Congolese village | World news". London: The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 September 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "90 per cent of people in LRA areas of Congo still live in fear of their safety, new Oxfam survey reveals | Oxfam International". Oxfam.org. 28 July 2011. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Uganda to head new military force to hunt for Kony". Hindustan Times. 18 March 2012. Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- Conal Urquhart, Joseph Kony: African Union brigade to hunt down LRA leader Archived 15 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, guardian.co.uk, 24 March 2012

- Butagiro, Tabu (30 April 2012) Khartoum aiding Kony rebels again Archived 27 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine Daily Monitor, Retrieved 26 December 2012

- "Joseph Kony: US doubts LRA rebel leader's surrender". BBC News. 21 November 2013. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Raymond Mujuni. "1200 LRA Fighters Set To Defect – UN". Uganda Radio Network. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- Report of the Parliamentary Committee on Defence and Internal Affairs on the War in Northern Uganda, 1997

- Onyango Odongo "Causes of Armed Conflicts in Uganda", Historical Memory Synthetic Paper, 2003 CBR Conference, Hotel Africana

- Ministry of Finance, Planning, and Economic Development, p.102

- The Hidden War: The Forgotten People, research study report by Afrika Study Center,2003

- "Meeting Report: Day 3". Africa, 2007 Consultation. Kibuye, Rwanda: Quaker Network for the Prevention of Violent Conflict. 29 March 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- Doom, Ruddy; Vlassenroot, Koen (1 January 1999). "The Lord's Resistance Army in Northern Uganda". Afraf.oxfordjournals.org. Archived from the original on 15 August 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- Drogin, Bob (1 April 1996). "Christian Cult Killing, Ravaging in New Uganda". Community.seattletimes.nwsource.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- Lamb, Christina (2 March 2008). "The Wizard of the Nile The Hunt for Africas Most Wanted by Matthew Green". The Times. London.

- McKinley Jr, James C. (5 March 1997). "Christian Rebels Wage a War of Terror in Uganda". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- McGreal, Chris (13 March 2008). "Museveni refuses to hand over rebel leaders to war crimes court". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- Boustany, Nora (19 March 2008). "Ugandan Rebel Reaches Out to International Court". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- Fraser, Ben (14 October 2008). "Uganda's aggressive peace". Eureka Street. 18 (21): 41–42. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- Chatlani, Hema. "Uganda: A Nation In Crisis" (PDF). California Western International Law Journal. 37: 284. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- Ghana, C. (9 August 2002). "Don't Praise The Lord". Africa Confidential. 43 (16).

- "Uganda: Demystifying Kony". ACR (69). Institute for War & Peace Reporting. 3 July 2006. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos (Summer 2008). "Conversion to Islam and Modernity in Nigeria: A View from the Underworld". Africa Today. 54 (4): 70–87. doi:10.2979/aft.2008.54.4.70.

- Frank Van Acker (2004). "Uganda and the Lord's Resistance Army: The New Order No One Ordered". African Affairs. 103 (412): 335–357. doi:10.1093/afraf/adh044.

- Gersony, Robert (August 1997). "Results of a field-based assessment of the civil conflicts in northern Uganda" (PDF). The anguish of northern Uganda. Kampala, Uganda: USAID. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- Doom, Ruddy; Vlassenroot, Koen (1999). "Kony's Message: A New Koine?". African Affairs. 98 (390): 13. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a008002.

- Harlacher, Thomas. "Traditional Ways of Coping with the Consequences of Traumatic Stress in Acholiland." Unpublished Dissertation. Department of Psychology, University Fribourg (Switzerland) 2009, p.10

- Singer, Peter W., Children at War, 2006, p. 20. Peter Singer puts the number over 14,000 children; Jimmie Briggs cites only 10,000 + children.

- Briggs, Jimmie, Innocents Lost: When Child soldiers Go to war, 2005, p. 105-144.

- Briggs, Jimmie, Innocents Lost: When Child soldiers Go to war, 2005, p. 109-110.

- Ottonu, Agenga (1998) The Path to Genocide in Northern Uganda Refuge, Vol 17, No 3. Retrieved 4 May 2012

- "Uganda: 'Sudan supporting Kony'". Bbc.co.uk. 30 April 2012. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Joseph Kony 2012: International Criminal Court chief prosecutor supports campaign Archived 26 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Telegraph, 12 March 2012

- Mugeere, Anthony (16 August 2001). "Uganda: SPLA Recruits in Ugandan Camps". Allafrica.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2003. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- "International Criminal Court : Situation in Uganda". 23 June 2007. Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Court moves against Uganda rebels Archived 19 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 7 October 2005

- Ugandans welcome rebel overture Archived 27 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 30 November 2005

- "Journeyman Pictures : short films : Meeting Joseph Kony". Journeyman.tv. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- Interpol push for Uganda arrests Archived 19 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 2 June 2006

- Regional Government Pays Ugandan Rebels Not to Attack Archived 7 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Human Rights News, 3 June 2006

- International Criminal Court (7 November 2006). "Statement by the Chief Prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo on the confirmation of the death of Raska Lukwiya" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008.. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- BBC News (23 January 2008). Uganda's LRA confirm Otti death Archived 24 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- BBC News (14 April 2008). Ugandan LRA rebel deputy 'killed' Archived 20 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- (14 January 2015) LRA commander Dominic Ongwen 'in Ugandan custody' Archived 1 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, Africa, Retrieved 14 January 2015

- Oluka, Benon Herbert and Ssekika, Edward (14 January 2015) Why USA held onto LRA man Archived 30 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine The Observer, Uganda, retrieved 14 January 2015

- "Senior LRA commander killed, says Uganda". News24. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- "The Lord's Resistance Army : The U.S. Response" (PDF). Fas.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- "Alimadi the US is not interested in going after the LRA". Sfbayview.com. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- Capaccio, Tony (14 October 2011). "Obama Sends Troops Against Uganda Rebels". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- Jeffrey Gettleman and Eric Schmitt (6 February 2009). "U.S. Aided a Failed Plan to Rout Ugandan Rebels". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- "LRA Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act of 2009". Resolve. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- Kavanagh, Michael J. (25 November 2010). "Obama Administration Asks for Funds to Boost Uganda's Fight Against Rebels". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- "Obama orders U.S. troops to help chase down African 'army' leader". CNN. 14 October 2011. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- "Obama sends 100 military advisers to fight Africa rebels". Today News. 15 October 2011. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- "The Lord’s Resistance Army: The U.S. Response" Archived 1 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 21 November 2011, CRS Report for Congress, Page 10

- Shanker, Thom; Gladstone, Rick (14 October 2011). "Obama Sending 100 Armed Advisers to Africa to Help Fight Renegade Group". New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Wittes, Benjamin (26 October 2010). "Lawfare " Human Rights Watch Responds". Lawfareblog.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Fact Sheet: Mitigating and Eliminating the Threat to Civilians by The Lord's Resistance Army". White House. 23 April 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- http://jackson.yale.edu/event/screening-of-my-star-in-the-sky-and-qa-with-filmmakers/

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "UPDF in Kony hunt accused of rape, looting". Observer.ug. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "African Union hunts Uganda rebel group – Africa". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

Further reading

- Allen, Tim; Vlassenroot, Koen (2010). The Lord's Resistance Army: Myth and Reality. Zed Books Ltd.

- Briggs, Jimmie (2005). Innocents Lost: When Child Soldiers Go to War. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00798-1.

- Green, Matthew (2008). The Wizard of the Nile: The Hunt for Africa's Most Wanted. Portobello Books. ISBN 978-1-84627-030-7.

- Jagielski, Wojciech and Antonia Lloyd-Jones. The night wanderers: Uganda's children and the Lord's Resistance Army. (2012). New York: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 9781609803506

- Lewis, Janet. 2020. How Insurgency Begins: Rebel Group Formation in Uganda and Beyond. Cambridge University Press.

- Singer, Peter W. (2006). Children at War. University of California Press.

External links

- Population surveys in Northern Uganda during and after the LRA, UC Berkeley and Tulane University

- Girl Soldiers – The cost of war in Northern Uganda, Women News Network – WNN

- Lord's Resistance Army, GlobalSecurity.org

- "A Case for National Reconciliation, Peace, Democracy and Economic Prosperity for All Ugandans", outlines and defends the LRA's political views.

- Invisible Children, advocacy group and documentary about LRA's child soldiers

- Uganda page, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre

- Human Security in Northern Uganda project, University of British Columbia (extensive links from before mid-2004)

- Survey of War Affected Youth (SWAY): Research & Programs for Youth in Armed Conflict in Uganda

- Radio France Internationale, LRA Dossier (in English)

- Crisis briefing on the LRA and violence in Uganda from Reuters AlertNet

- Research at UC Berkeley's Human Rights Center Initiative for Vulnerable Populations

- CandaceScharsu.com, Candace Scharsu photographs the victims of the LRA

- LRA Crisis Tracker

- Kony 2012 Video, The Brouhaha, The Long Hunt For A War Criminal, And How We Got Here

- LRA, Boko Haram, al-Shabaab, AQIM, and Other Sources of Instability in Africa: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred Twelfth Congress, Second Session (25 April 2012)

- U.S. Policy to Counter the Lord's Resistance Army: Hearing before the Subcommittee on African Affairs of the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, One Hundred Twelfth Congress, Second Session (24 April 2012)

- An End to Child Soldiers

- "Slaves: Human Bondage In Today's World", a 2019 Deutsche Welle television program documenting LRA use of sex slavery, enslavement of child soldiers, and other atrocities through interviews with former LRA commander Caesar Acellam, UN expert Matthew Brubacher, and victims; narrated in English