Lydians

The Lydians (known as Sparda to the Achaemenids, Old Persian cuneiform 𐎿𐎱𐎼𐎭) were an Anatolian people living in Lydia, a region in western Anatolia, who spoke the distinctive Lydian language, an Indo-European language of the Anatolian group.

Questions raised regarding their origins, as defined by the language and reaching well into the 2nd millennium BC, continue to be debated by language historians and archeologists.[2] A distinct Lydian culture lasted, in all probability, until at least shortly before the Common Era, having been attested the last time among extant records by Strabo in Kibyra in south-west Anatolia around his time (1st century BC).

The Lydian capital was at Sfard or Sardis. Their recorded history of statehood, which covers three dynasties traceable to the Late Bronze Age, reached the height of its power and achievements during the 7th and 6th centuries BC, a time which coincided with the demise of the power of neighboring Phrygia, which lay to the north-east of Lydia.

Lydian power came to an abrupt end with the fall of their capital in events subsequent to the Battle of Halys in 585 BC and defeat by Cyrus the Great in 546 BC.

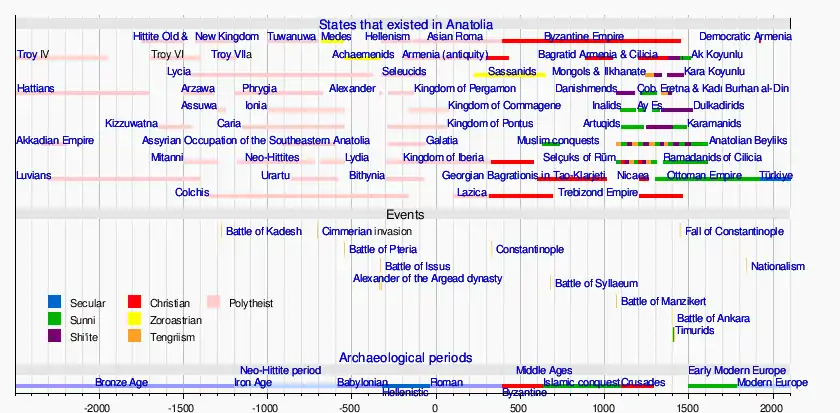

(7th century BC boundary in red)

Sources

Material in the way of historical accounts of themselves found to date is scarce; the knowledge on Lydians largely rely on the impressed but mixed accounts of ancient Greek writers.

The Homeric name for the Lydians was Μαίονες, cited among the allies of the Trojans during the Trojan War, and from this name "Maeonia" and "Maeonians" derive and while these Bronze Age terms have sometimes been used as alternatives for Lydia and the Lydians, nuances have also been brought between them. The first attestation of Lydians under such a name occurs in Neo-Assyrian sources. The annals of Assurbanipal (mid-7th century BC) refer to the embassy of Gu(g)gu, king of Luddi, to be identified with Gyges, king of the Lydians.[3] It seems likely that the term Lydians came to be used with reference to the inhabitants of Sardis and its vicinity only with the rise of the Mermnad dynasty.[4]

Herodotus states in his Histories that the Lydians "were the first men whom we know who coined and used gold and silver currency".[5] While this specifically refers to coinage in electrum, some numismatists think that coinage per se arose in Lydia.[6] He also states that during the kingship of Croesus, there was no other Asia Minor ethnos braver and more militant than the Lydians.[7]

Customs

According to Herodotus, once a Lydian girl reached maturity, she would ply the trade of prostitute until she had earned a sufficient dowry, upon which she would publicize her availability for marriage. This was the general practice for girls not born into nobility.[8]

He also attributes the Lydians with inventing a variety of ancient games, notably knucklebones, claiming the games' rise in popularity to be during a particularly severe drought, where the games afforded the Lydians a psychological reprieve from their troubles.[9]

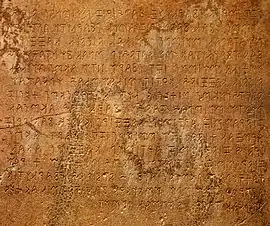

Language and script

Lydian texts discovered to date are not numerous and usually short, but close liaisons maintained between leading scholars of Anatolian linguistics enables constant impetus and progress in the field, new epigraphical findings, evidence being added and new words being recorded continuously. Nevertheless, a real breakthrough for the understanding of the Lydian language has not occurred yet.

Presently available texts begin around the mid-7th century and extend until the 2nd century BC, which leads one scholar to conclude, "Lydians wrote early, but [in the light of the available sources, it seems] they did not write much."[10]

Religion

A number of Lydian religious concepts may well go back to the Early Bronze Age and even Late Stone Age, such as the vegetation goddess Kore, the snake and bull cult, the thunder and rain god and the double-axe (Labrys) as a sign of thunder, the mountain mother goddess (Mother of Gods) assisted by lions, associable or not to the more debated Kuvava (Cybele). A difficulty in compounding Lydian religion and mythology remains as reciprocal contacts and transfer with ancient Greek concepts occurred for over a millennium from the Bronze Age to classical (Persian) times. As pointed out by archaeological explorers of Lydia, Artimu (Artemis) and Pldans (Apollo) have strong Anatolian components and Cybele-Rhea, the Mother of Gods, and Baki (Bacchus, Dionysos) went from Anatolia to Greece, while both in Lydia and Caria, Levs (Zeus) preserved strong local characteristics all at the same sharing the name of its Greek equivalent.

Among other divine figures of the Lydian pantheon which still remain relatively obscure, Santai, Kuvava's escort and sometimes a hero burned on a pyre, and Marivda(s), associated with darkness, may be cited.

In literature and arts

Niobe, daughter of Tantalus and Dione and sister of Pelops and Broteas, had known Arachne, a Lydian woman, when she was still in Lydia/Maeonia in her father's lands near to Mount Sipylus, according to Ovid's account. These eponymous figures may have corresponded to the obscure ages associated with the semi-legendary dynasty of the Atyads and/or Tantalids, and situated around the time of the emergence of a Lydian nation from their predecessors and/or previous identities as Maeonians and Luvians.

Several accounts on the dynasty of Tylonids succeeding the Atyads and/or Tantalids are available and once into the last Lydian dynasty of Mermnads, the legendary accounts surrounding Ring of Gyges, and Gyges's later enthronement to the Lydian throne and foundation of the new dynasty, by replacing the King Kandaules, the last of the Taylanids, this in alliance with Kandaules's wife who then became his queen, are Lydian stories in the full sense of the term, as recounted by Herodotus, who himself may have borrowed his passages from Xanthus of Lydia, a Lydian who had reportedly written a history of his country slightly earlier in the same century.

Several expressions on Lydians were in common use in ancient Greek and in Latin languages, and a collection and detailed treatment of these were done by Erasmus in his Adagia.

There are also several works of visual arts depicting Lydians or using as theme subject matters of Lydian history.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to People of Lydia. |

- Lydia

- Lydia (satrapy)

- Lydian Treasure (Karun Treasure)

- Luvian language

References

- Darius I, DNa inscription, Line 28

- Ivo Hajnal. "Lydian: Late Hittite or Neo-Luwian?" (PDF). Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen, Universität Innsbruck.; M. Giorgieri; M. Salvini; M.C. Tremouille; P. Vannicelli (1999). Licia e Lidia prima dell’Ellenizzazione. Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Rome.

- Pedley, John G., Ancient Literary Sources on Sardis, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972, № 292-293, 295

- Ilya Yakubovich, Sociolinguistics of the Luvian Language, Leiden: Brill, 2010, p. 114

- Herodotus, Histories 1.94

- M. Kroll, review of G. Le Rider's La naissance de la monnaie, Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau 80 (2001), p. 526.

- Herodotus, Histories 1.79

- Herodotus, Histories 1.93

- Herodotus, Histories 1.94

- George M.A. Hanfmann; William E. Mierse, eds. (1983). Sard from prehistoric to Roman times: results of the Archaeological Exploration of Sard, 1958-1975. Harvard University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-674-78925-8.

Sources

- Christopher Roosevelt (2009). The Archaeology of Lydia, from Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51987-8.

- George M.A. Hanfmann; William E. Mierse, eds. (1983). Sard from prehistoric to Roman times: results of the Archaeological Exploration of Sard, 1958-1975. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-85404-630-0.